Today we are pleased to introduce James P. Leary as part of the Wisconsin Historical Museum’s History Sandwiched In lecture series. The opinions expressed today are those of the presenters, and are not necessarily those of the Wisconsin Historical Society, or the museum’s employees. Born and raised in Rice Lake, Wisconsin, James P. Leary is Professor Emeritus of Folklore and Scandinavian Studies, at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he co-founded The Center for the Study of Upper Midwestern Cultures. His many books and documentary productions include: “Wisconsin Folklore,” “So Ole Says to Lena,” “Polkabilly,” “Accordions in the Cutover,” “Down Home Dairyland” with Richard March, the Grammy nominated “Folksongs of Another America,” and “Pinery Boys” with Franz Rickaby and Gretchen Dykstra. So if you could join me in welcoming James P. Leary. (applause)

Thanks everyone, and thanks Katie for the nice introduction. I’m a folklorist, and as Katie mentioned, I was born and raised in northern Wisconsin. And folklorists really engage in cultural documentation, with diverse peoples and my own work has been in the upper Midwest. Working with diverse indigenous peoples, the old European immigrant ethnic communities. With new immigrants. Also with people working in a number of occupational traditions. I’ve done stuff with iron workers, with farmers, with factory line workers, and also with working loggers in the region. Growing up in Rice Lake, I was born in 1950. I had the good fortune of really growing up in a farming and logging town. And there were a lot of old lumberjacks around when I was a kid. People who had worked in the heyday of the lumber camps. Most of the ones who were still living when I was growing up were born maybe in the 1880’s and 1890’s and had worked kind of toward the tail-end of big camps. But I had a neighbor down the road who was born in 1885.

His parents a had come over from Ireland. His father had worked in Chippewa Valley lumber camps. And he worked a little in Wisconsin, but more in Minnesota near Rainy Lake. His name was George Russell. He was a timber scaler in the woods. Also in my hometown was a guy named Otto Rindlisbacher, who I’ll mention a little bit later. But he ran the Buckhorn Tavern, which was a classic up-north Museum Bar. And as a young man he was of Swiss background. He made cheese of course, but he’d also worked in the woods and worked in sawmills.

And he was a fiddler and a fiddle-maker. And his place, his bar had the world’s largest collection of odd lumberjack musical instruments. Or so he called them, on a postcard from the Buckhorn Tavern. And his place was a hangout for musicians. And I went in there now and then with my dad when I was a young kid. And then later on, Otto lived until 1975 when he was 80 years old. And I was able to– I was 21 by then, and able to go into the Buckhorn and have a drink and hang out, and talk with him a little bit. In the early 1970’s I also began to study folklore. I got a Masters at North Carolina and a Ph.D. at Indiana.

And along the way I discovered this book “Ballads and Songs of the Shanty-Boy” by Franz Rickaby. And looking at the forward of it, I saw that he acknowledged the help of Otto Rindlesbacher, from my hometown. And he also included songs from people in Ladysmith, Eau Claire, Chippewa Falls, Gordon, other places in northern Wisconsin, with which I was quite familiar. When I was kind of a scrappy young grad student in the mid-seventies. I found a used copy of this book. It was published originally in 1926. It was a scarce book, I paid $50.00 for it, which was a huge fortune to me as a starving graduate student then. And it’s been an interest ever since. A few years ago, the University of Wisconsin Press asked if there were any older titles that had gone out of print.

And this book had originally been published by Harvard University Press. And the UW Press was wondering if there was something, some books we could bring back, having to do with regional folklore, bring it back into print. Then I suggested this, and I was very lucky in looking into doing a new edition, to be able to be in contact with, and eventually collaborate with Franz Rickaby’s granddaughter, Gretchen Dykstra. Rickaby himself was born in 1875, 1879 rather, in Rogers, Arkansas. His father was English. His mother was of German background. And they were a family that kind of scuffled to get by. He was a high school dropout as a young man. He kind of wandered around picking apples and doing various laboring jobs.

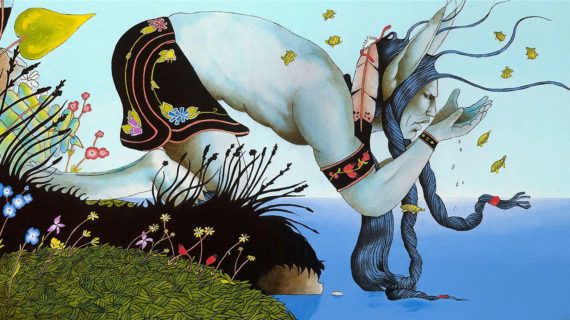

But his father was a church organist and a music teacher, and he had music in his heart. And kept that up and then finally, late in his teens, returned and got a high school degree, and then went on to get degrees from Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois, and eventually from Harvard. This is a photograph of him in, being Mercury like, quite a yoga move one would say today I suppose. A very energetic fella, but during his early travels he contracted rheumatic fever. And later in his life as he got into his 30’s, his health began to decline. He was at the Mayo Clinic periodically. Eventually he and his wife and young son moved out to California for better air, but he died in 1925, a few months before his book “Ballads and the Songs of the Shanty-Boy” was published. So he never got to see it. His wife remarried a number of years later.

She married a guy named Clarence Dykstra, who became the Chancellor at the University of Wisconsin in the 1940’s. And as a result of that, Rickaby’s field notebooks from a field trip that he made in 1919 are in the Wisconsin Historical Society. And his unpublished collection of other folk songs, mostly from the upper Midwest, are in the Mills Music Library here on campus. But his granddaughter, Gretchen Dykstra, who grew up only hearing a few stories about him, seeing a few family photographs, became curious as she got into her 60’s, and began to wonder more about her grandfather. She began going into a family cache of writings, letters, photographs, publications, that he’d had. And began to track down elements of his life. Including eventually going on a trip. Retracing some of his field work and going to various places where he had lived. And I mentioned fortuitously, as I was beginning to work with UW Press on a new edition of Rickaby’s book, I ran into Gretchen who in turn, was at work on this kind of biography and genealogical quest about her grandfather.

And we threw in together. So what we’ve done, we’ve taken his, Rickaby’s 1925 book “Ballads and Songs of the Shanty-Boy,” and we’ve added new material to it. And here’s a slide of the table of contents. We have a first part where I wrote a little introduction about Rickaby’s background. And he was one of a number of people, who in the early 20th century were, what nowadays gets called “song-catchers,” people who were in search of narrative folk songs. Mostly in the English language, sometimes having roots to the British Isles. Circulating an oral tradition in North America. So I did a little introduction about that. Then there’s an extensive, very well written, I might add, an illustrated biography of Rickaby that also combines with Gretchen’s genealogical search and retracing his steps.

So it’s a really nice vivid piece. And then we reproduce the songs that Rickaby gathered from lumberjacks. Mostly in northern and lower Michigan, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, northern Wisconsin, northern Minnesota. And then there were a number of people who had worked in the woods in Ontario. Mostly people of Irish background, if any of you are familiar with that kind of Irish-Canadian folk music group called “Leahy.” They’re a bunch of brothers and sisters who perform. One of their ancestors settled in Omemee, North Dakota, (laughs) which is where Franz Rickaby encountered him. So we have his collection of 51 folk songs circulating in the lumber camps. Most of these songs are songs about work in the woods. Triumphs, tragedies, people being crushed during log jams and exciting things like that.

Or having limbs fall on them, or being cut in half in a sawmill. But there also are contests in skidding and who could do the best work. There are sometimes militant labor songs, the shanty man’s Marseilles, evoking the French soldier’s song, associated with the Paris Commune. And there also are a lumberjack alphabet. A is for axes, as all of you know, and B is for boys who can wield them also. He didn’t include the raunchy version of this unfortunately, but that’s in my “Folk Songs of Another America,” from subsequent field recordings. And then there were also– It’s riddled with little catalogs or chronicles of work in the woods, and little verse, or a couple-line portraits or characterizations of different people who worked in the woods. So he has a lot of those but he also, as you can see here at number 41. Well actually starting even earlier number 39.

There are a lot of songs of being on ships and sailing. And that’s partly because work in the woods was seasonal. It was done in the winter time with a frozen ground and ice roads. You could move those heavy timbers with horse and oxen. And then what would people do the rest of the time? Some of them had small farms to which they returned. Some went out eventually to the Dakotas and worked on threshing crews. Some worked in sawmills. But more than a few worked on Great Lakes vessels and sailed in the age of sailing ships on the Great Lakes. And so those repertoires of songs from those different occupational traditions came over.

A number of the songs like “Morrissey and The Russian Sailor,” and “Heenan and Sayers” are songs. They’re Irish-American songs. And a large number of workers who were also singers in the lumber camps were of Irish extraction. And Rickaby was the first really to identify the Irish influence in the lumber camps, on tunes, on the composition if songs, and also on singing style. And Irish were influential to the extent that the people of other backgrounds, if they were singing in English, took on an Irish style. The third part of the book has songs from Rickaby’s manuscripts that are in the Mills Music Library. There are several hundred of these and I picked out about 14 that had to do with the upper Midwest. They expand the frame a little bit. They include songs in German and about Germans.

They include Scandinavian, especially Norwegian songs. They include local songs about deer hunting. They include even a Ho-Chunk song. This is it. He says, “This is my only attempt so far “to record a melody sung by an Indian.” This is Rickaby’s little notes. “I heard a young fellow of the Winnebago sing at the Kiwanis Club luncheon when I was in Eau Claire.” And he goes on to observe that he had him sing afterwards, and noted down, Rickaby did not make recordings. He transcribed, he was a violinist, so he transcribed the tunes in quick notation. And here he observes, “I can’t believe he was a very good singer. “The young fellow called himself Chief White Eagle.” Now I think this is the ethnocentrism of Rickaby at work.

Because in fact I’m pretty sure this is Winslow White Eagle, who was revered as a very fine Ho-Chunk singer with quite a range and command, vocal command and a broad repertoire. Back in the late 80’s and early 90’s I worked quite a bit with Ken Funmaker Sr. of the Ho-Chunk Nation, helping him establish the Hocak Wazijaci language and culture center, the Ho-Chunk Nation’s institution of language and culture programs. And Ken himself was a remarkable singer. He had a repertoire of about 300 Ho-Chunk songs. His sons carry on the group called the Wisconsin Dells Singers, carry on the Ho-Chunk repertoire. And Ken knew Winslow White Eagle and described him as a remarkable singer. He was also a silversmith. Kenny used to hang out with him when he was living in Lyndon Station and heard him sing many times.

Winslow White Eagle was also recorded by Frances Densmore, an early recorder of American Indian music working for the Smithsonian Institution’s Bureau of American Ethnology. She was from Red Wing, Minnesota and did extensive recordings of Ho-Chunk, as well as Menomonie, Lac du Flambeau, Ojibwe, in northern Minnesota as well. Here we see a photo of Winslow White Eagle as a guide in the Wisconsin Dells. And he… He was involved with the Stand Rock Indian Ceremonial. And he was actually recorded again for the Library of Congress in 1946 at Wisconsin Dells. But here he is on a postcard. Even though Rickaby denigrated or had his misgivings about the skill of White Eagle as a singer, it’s noteworthy that he paid attention to it. We see a glimpse of Franz Rickaby here in two different settings.

One is in his sort of traveling clothes. In some ways there was a, not only an economic reality of, you know, homeless and itinerant workers in that era. If one reflects back on labor in the United States and even looks to it in the contemporary era, there are a number of occupations that demand intensive seasonal labor. Whether it’s picking apples or harvesting various kinds of crops. And back in the day of lumber camp of course you could only work in the woods in the winter. And so people did seasonal work, but in between a lot of times they were homeless. Wandering around, and it’s obviously not that unusual of a situation globally or nationally either. Rickaby himself took part in this, had a strong sympathy for it. But because of his intellectual brilliance and the fact that he came from a poor but well-educated family, he was able to make his way eventually to Harvard University where we see him in his study here, a little bit prior to WWI.

There he was influenced by a number of ballad and folk song scholars. One had died by that time, Francis James Child on the left, who is associated with the so-called Child Ballads, English and Scottish popular ballads. Child was a Professor of Modern Languages at Harvard as a young man. He had kind of made the European tour. He had studied at Heidelberg. He became influenced by the Grimms and others. The Grimms were of course interested in Germanic, but comparative folk tales, as well as legends, but they also had an earlier interest and were connected with people interested in folk songs. Child made folk songs his interest, especially English and Scottish folk songs. He never went out into the field.

You can see him here in his arm chair, a so-called arm chair scholar, as opposed to Rickaby, who looks ready to go out and tramp around. But he corresponded with various people and he compiled a five-volume set of books of 305 English and Scottish popular ballads with various variations and historical and linguistic background and annotations and so forth. His main disciple at Harvard, who in fact was Rickaby’s teacher, was George Lyman Kittredge, also an arm-chair scholar, who you can see sitting in his arm chair. That’s actually a portrait that was painted of him. But he was very much a scholar of these old texts. However, unlike Child, he realized that these songs were not only confined to the historical record in England and Scotland, but rather they were continuing to circulate and undergo variation in oral tradition, and that many people that had come over from the British Isles sang these songs and were continuing to sing them in various parts of the United States. Kittredge was also more open-minded about other kinds of songs that may have emerged in the United States. And there were a few other people at the time that Rickaby was working, who had this interest. One of them was John Lomax, who you see here on the right, in his recreation of his historic 1933 field recording of Huddie Ledbetter or Ledbelly, where he was accompanied by his more famous son, Alan Lomax.

But John Lomax grew up in east Texas not far from the Chisholm Trail. He heard cowboy songs while he was growing up. He began to put them together and in 1910, he published a book called “Cowboy Songs and other Frontier Ballads.” He was savvy enough, very much a promoter, to enlist the former Rough Rider Theodore Roosevelt, the former president of the United States, to write a forward to Cowboy Songs and other Frontier Ballads. So this was in some ways the first major study to look at folk songs that were either composed thoroughly in the United States or were songs from British and Irish origin that were made over and localized and redone, to situate themselves in the United States. It was also the first major study of the tradition of workers’ songs. Generally of men who were in semi-isolated conditions for extended periods of time. You know, cowboys on the trail drive or out tending the herds, and then getting together at night. Similarly sailors, whether on the Great Lakes or the salt seas, had song traditions, as did people who worked in lumber camps. And that included of course, Maine and New Brunswick, the maritime provinces of Canada, across to Ontario on the Canadian side and the United States across into New York State especially, and then jumping over into Michigan, especially northern and lower Michigan, the U.P., northern Wisconsin, northern Minnesota, and then out on into the Pacific Northwest.

So Rickaby was inspired by Lomax, who had also studied in Harvard. Because of his earlier tramping days, he took into his mind, this idea that he would “auto tramp” as he called it. Fundamentally hitchhike with his fiddle. He would sing for his supper. And he thought he would travel from– He’d actually been the organizer of all the caddies at a big resort for rich people from Chicago and Charlevoix, Michigan. He started there and then had to take the ferry across into the U.P. and made his way from there, and he was on his way eventually to Grand Forks, North Dakota, because by 1917 he had begun to teach in the English Department at University of North Dakota. So you see the Grand Forks Herald in 1919 is giving a little bit of play-by-play. There were periodic stories about the Rickaby’s here, and now he’s somewhere else. And his field journals from that trip are in the Historical Society here.

We see a little bit of his route, as well as indications on this map of other places where he had recorded songs from people in Wisconsin. As well as Michigan, Minnesota, and North Dakota. This trip however wasn’t very successful, with regard to finding people who sang songs from lumber camps. I think he only got one song and he also– Although he was fixed on finding songs sung in English, a lot of the people that he encountered were Finnish, and French-Canadian and German, and Swedish and Italian and Croatian. They were new immigrants. By the time he was doing this, was in 1919. This is one of his photographs here on the left of tar-paper shacks in the U.P. On the right he’s in Cloquet, Minnesota. So he pretty much struck out on this particular trip.

So what he began to do, because University of North Dakota was involved with educating teachers, he was familiar with the so-called teachers college or normal school set up. He knew that in many cases, teachers were the children of people, especially in these regions, who may have worked in the lumber camps. He arranged for a number of programs in places like Eau Claire, quite notably, where he would give a little concert with his violin, and also singing some of these songs. He would invite people to come and then in many cases there were people who knew songs. Some were men, but there were also many women who were his sources of lumber camp songs, even though they hadn’t worked in the lumber camps, they knew the repertoire through their relatives who had worked in the camps. And so he was able to acquire quite a few songs, but he got a lot help from a guy named William Bartlett, who was born in the state of Maine, had moved as a young boy with his parents in the 19th century to Eau Claire. He was a contractor there. But he was also very much interested in history of the area. And he put out a great book later in the 1920’s called, “History, Tradition and Adventure “in The Chippewa Valley,” that includes a really cool chapter on humor in the lumber camps.

He was a source for Rickaby. They had a long correspondence, as well as meeting when Rickaby was in Eau Claire, and you see here a little account of Rickaby playing on the fiddle delighting a large audience of students and faculty of the Eau Claire Normal School. And through Bartlett, Rickaby encountered or met a number of other people. One was a guy named William N., William Neal Allen or Billy Allen, who also took on the pen name, as you can see on the left right under the photo, of Shan T. Boy, or shanty boy. And in the early 19th or 20th century, the term lumberjack wasn’t used that much. People who, men who worked in the woods, referred to themselves as “The Boys” or “Shanty Boys,” and the word shanty that we’ve– I grew up hearing connection with mostly ice shanties, you know put up for ice fishing, comes from Gaelic, it means small house. Shanty. And so it refers in some ways to the rough buildings in which the woods workers found themselves. But Allen was from– He was born in New Brunswick and as a young man moved to Wisconsin with his family, or his parents rather.

He never married, but he was based mostly in the Wausau area. He was a timber cruiser, which meant that he would travel in areas where lumber companies wanted to bid on or get a sense of the cost effectiveness, the quality of timber in a particular area, where to put their camps should they invest in it and that sort of thing. He was very good at what he did. He was also, he was of Irish extraction and very much poetically inclined. And in the 1870’s, he began to compose a number of poems having to do with life in the lumber camps, which he would sing. He also printed them out on little handbills or broadsides. At least three of them got into oral tradition: “Shanty Boy and the Big Eau Claire,” “Driving Saw Logs on the Plover,” and, ah… the other one that’s escaping me, right now. But some of these songs were sung not only throughout Wisconsin, but in the U.P. and Ontario, in Minnesota, even back further east in New York State.

And in fact a fellow with a stage name of Pierre Ledoux, sang one in a New York musical, sang “Driving Saw Logs on the Plover,” and recorded it on a 78 rpm record in a kind of a cheesy parlor, crooner style. But Allen lived until, well into the 1920’s. You can see a little obituary that made the news in the Wisconsin State Journal in 1929. He was a, as many Irish were of his generation, a lifelong member of the Democratic Party, and sometimes wrote satiric political verse. One of the funniest ones involves Calvin Coolidge, known as “Silent Cal” the president from Vermont, who famously didn’t seek a second term using the phrase, “I do not choose to run.” And the thing that galled Allen was that there was a tract of land that’s now the Sylvania National Forest, on the border between Wisconsin and the U.P. That was owned by eastern timber interests. There’s still virgin pine and hemlock there. It was closed off at the time to any ordinary people, but the wealthy could go there and stride around and fish for trout and enjoy the wildlife, which Coolidge was doing. And so in the 1890’s another timber cruiser, who Allen knew from Rhinelander, Eugene Shephard, had invented this monster of the Northwoods, “The Hodag.” And so in the imagination of Billy Allen, Calvin Coolidge is walking through the woods and he encounters a chipmunk and stands boldly in front him and says, “I do not choose to run.” When he hears the chipmunk chirping.

And then goes a little further and there’s a porcupine kind of ambling along, and he stands up and “I do not choose to run.” But then he’s walking a little further and he begins to hear this growling, and the bushes and the trees start to shake and out of the woods comes this fierce Hodag and he says, “By God! I think I’ll run.” (laughs) But at any rate, through William Bartlett, Rickaby was able to meet Billy Allen. And, at the time when Rickaby was seeking folk songs it was not the custom of folk song catchers to pay much attention to the singers themselves. And it was also thought that folk songs were entirely anonymous, as if they’d come out of a throng of people, or something like that. So Rickaby was the first one to set down a full biography, a really full biography of an American folk song singer. And also to be able to look at songs which Allen had actually composed and that had undergone different variation in oral tradition. Bartlett also provided Allen with a set of photographs that are now in the iconic graphic collection of the Wisconsin Historical Society. Photographs that he had had made a little bit earlier of lumber camp life. And these were used to illustrate the original publication of “Ballads and the Songs of the Shanty Boy,” and we reproduced them the new edition. So we see people her with their pipes and their socks in the straw bunks, the deacons seat that’s strewn across the bunkhouse.

We also see, and this we use as a cover image, a bunch of loggers posing, probably on a Saturday afternoon, or a Sunday afternoon, when a photographer would have come to the camp, with the Gabriel, or the dinner horn there. Another fella has a fiddle, and then several have cant hooks and jam pikes for moving the logs around as well. And you see the rude shanty behind them, And this a kind of a dramatic photo of a wanigan, a kind of mobile cookhouse for feeding people on the river drives, traversing the rapids. So it was through Bartlett that Rickaby was able to acquire all these images. And I think it was also through Bartlett that Rickaby was able to meet Otto Rindlesbacher, who I mentioned at the outset. Here he is, this is a later photo that was a postcard from the Buckhorn Tavern. This is kind of how I remember it in the 1950’s with a number of lumber camp instruments. Some of which Rickaby made, displayed– I mean Rindlesbacher made, displayed behind him. Okay, we want to have a little bit of an opportunity to hear some of these songs.

I mentioned before the importance of the Irish style in the camps. This is a French-Canadian guy Emory DeNoyer. He was blinded as a young boy in a shotgun accident. But he was very enterprising He had a good ear, he had a great voice, a good memory. And he was living in Rhinelander. He acquired from local old-timers, a lot of lumberjack songs. He had a brother who would take him to camps in the Rhinelander area and he would sing for tips. In the 1940’s when Rhinelander established their logging museum, he was kind of well known and associated with that site. And Lance Trapman Thomas of the University of Wisconsin, made recordings for the Library of Congress, and recorded this song “Shanty Man’s Life.” It’s sung very much in an Irish style, kind of a high-pitched tenor style, sung unaccompanied. It’s one of these catalogs and in Rickabys collection, it’s called “Jim Porter’s Shanty Song.” Well, just listen to part of it. ‘Cause it’s a long song, it goes on for about five minutes.

All you jolly fellows come listen to my song It’s all about the pinery boys and how they get along They’re the jolliest lot of fellows so merrily and fine They will spend their pleasant winter months in cutting Down the pine Some will leave friends and homes and others they Do love dear And into the lonesome pine woods Their pathway they do steer Into the lonesome pine woods all winter to remain Awaiting for the spring time to return again – [Leary] So we’re starting the third verse now. Spring time comes O glad will be its day Some return to home and friends while others go astray The sawyers and the choppers they lay their timber low The swampers and the teamsters they haul it to and fro Next comes the loaders before the break of day Load up your sleighs 5,000 feet ‘Till the river haste away Noon time rolls around our foreman loudly screams Lay down your tools me boys And we’ll haste to pork and beans

– Okay, so they get their food and it kind of goes on, has a little bit on the rivalry between the various workers. And then it ends up with the time in the woods being over. But then a little break, and people are wanted on the lumber, on the river drive. And so it kind of goes on like that. Another noted song, and this will be kind of close to wrapping up, is “The Pinery Boy” and this is one that was acquired by Rickaby from a Mrs. Olan of Eau Claire. We don’t know too much about her.

But it’s a song with an old Irish tune, and it’s actually adapted from a song from the Isles, from across the Atlantic, about the death of a sailor. A woman was lamenting news about her lover the sailor boy. It was, appealed to Otto Rindlesbacher and his wife Iva, who was seen here with a Viking cello, a pitchfork soundbox, one string instrument, modeled on the Norwegian psalmodicon. And in 1938 they were asked by the National Folk Festival to do a program of lumberjack songs, first in Chicago and then in Washington D.C. in 1939. And one of the tunes that Iva played on the Viking cello was ‘The Pinery Boy’ It had a lot of appeal. It’s been recorded by lots of people, including a kind of doomy goth-rock Australian guy Nick Cave. But kind of a really cool version is by a sort of Madison based super-group, The Emporors of Wyoming, that has Butch Vig, who ran Smart Studios, and produced Nirvana, and also played in the group, Garbage, that’s still going periodically, and teaming up with a guy named Phil Davis who used to write a lot for Isthmus and played in earlier bands like Spooner and Fire Town around Madison. So we’ll hear a little bit of their version of “The Pinery Boy.” And there’s a very cool video of it up on YouTube, if you want to look on YouTube, if you want to look at that at some point. Oh father, father, she said build me a boat Down the Wisconsin River so I may float And every raft I pass Bring me joy I will ask for my Sweet pinery boy So she was rollin’ Down the stream She saw three rafts All in a string – And of course she sees these raftsmen coming and they give her the bad news that he fell on the rocks, or drowned near Lone Rock, or something like that.

And the Wisconsin River is over his grave. Oh pilot pilot Tell me true Is my sweet Willy boy Among your crew – Okay. No, he’s not among the crew because he’s gone. So I wanted to kind of end with that just to show that I think these songs still have power. They’re capturing people’s imagination. They were a pioneering effort by Franz Rickaby. And in addition to capturing the songs of lumberjacks in the region, he also got songs from other ethnic groups including Ho-Chunk in the area. We’ve tried to put it all together in this new edition. In my introduction I call attention to some of newer recordings of these old songs by a number of people. So thank you very much for your kind attention and patience with the technical stuff too. Thank you. (applause)

Search University Place Episodes

Related Stories from PBS Wisconsin's Blog

Donate to sign up. Activate and sign in to Passport. It's that easy to help PBS Wisconsin serve your community through media that educates, inspires, and entertains.

Make your membership gift today

Only for new users: Activate Passport using your code or email address

Already a member?

Look up my account

Need some help? Go to FAQ or visit PBS Passport Help

Need help accessing PBS Wisconsin anywhere?

Online Access | Platform & Device Access | Cable or Satellite Access | Over-The-Air Access

Visit Access Guide

Need help accessing PBS Wisconsin anywhere?

Visit Our

Live TV Access Guide

Online AccessPlatform & Device Access

Cable or Satellite Access

Over-The-Air Access

Visit Access Guide

Passport

Passport

Follow Us