The cost, complexity and very local scope of Eau Claire's PFAS response

After testing found "forever chemicals" in multiple municipal drinking water wells used by Eau Claire, the city has taken steps to mitigate this contamination, but it's an expensive and time-consuming problem faced by communities around Wisconsin.

By Will Cushman

November 16, 2021 • West Central Region

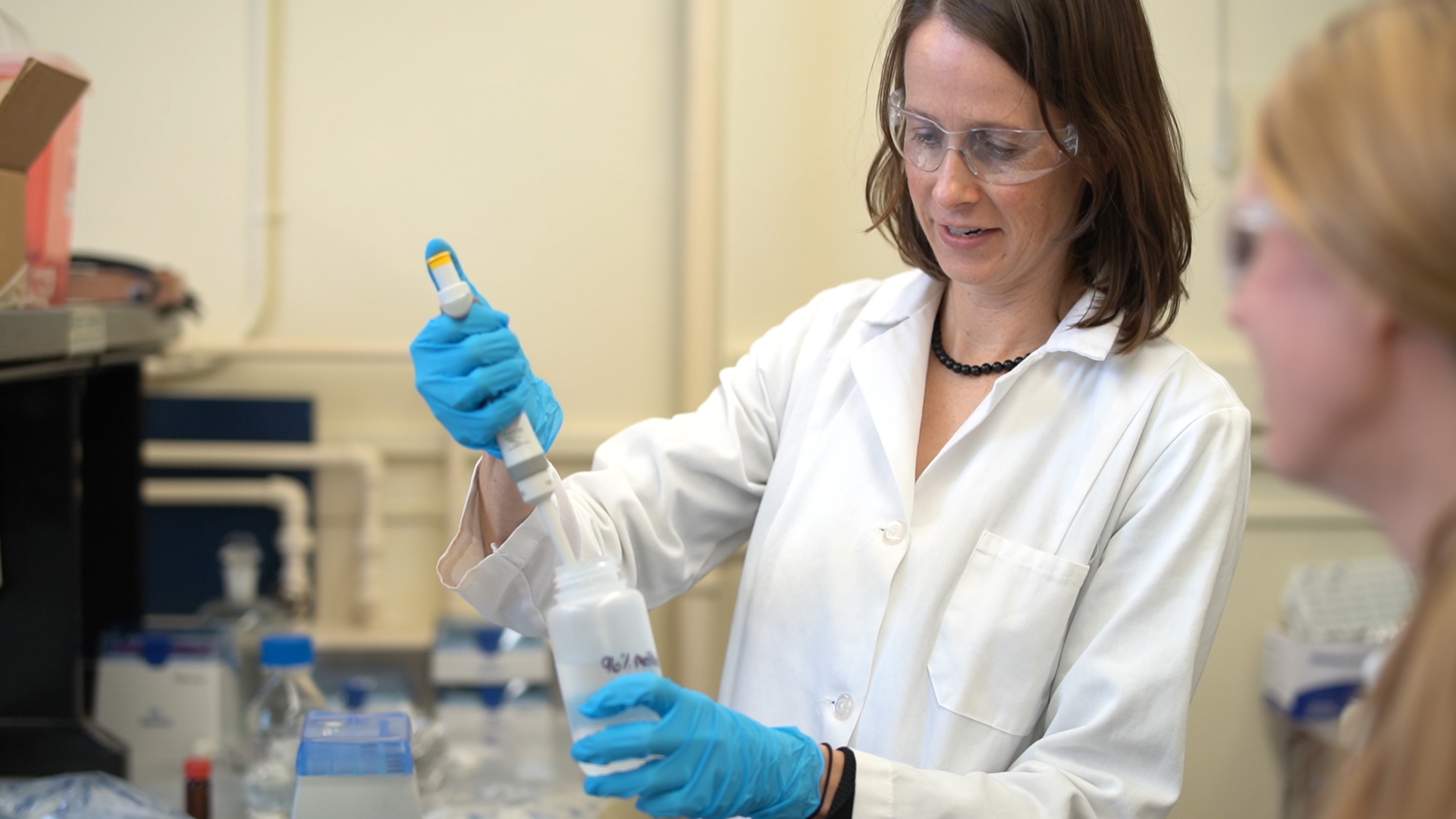

Understanding the scope of PFAS contamination around Wisconsin is based on scientific research and testing that is focused on identifying incredibly miniscule amounts of these "forever chemicals" in water. (Credit: Courtesy of Bonnie Willison / Wisconsin Sea Grant)

Most Wisconsinites are in the dark about how much PFAS, if any, might be pouring from their taps. In Eau Claire, though, the scope of a statewide water pollution problem is clearer, to a degree.

In July 2021, the city’s utilities department turned off the taps at four of its 16 wells, which are pumped to provide drinking water to tens of thousands of residents. The reason? Testing showed the wells were drawing water contaminated with PFAS.

PFAS are a class of more than 5,000 chemicals with properties that make them useful in a wide range of products manufactured since the mid-20th century, from non-stick skillets to rain jackets to foams that work better than water for putting out intense fires.

In the 21st century, though, scientists have discovered that a number of PFAS chemicals — some of which remain in the environment indefinitely and are found in trace amounts all over the world — carry risks to human health and ecosystems. Excessive exposure to certain PFAS chemicals has been linked to thyroid dysfunction, fertility problems and even cancer.

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services has warned that 12 individual PFAS chemicals and four combinations of the chemicals are potentially hazardous to human health when found above certain levels in drinking water. That’s why officials at the Eau Claire water utility were concerned and moved to take action when they found some of these flagged chemicals beyond levels deemed safe in the offending wells.

An expensive problem

Eau Claire residents wouldn’t even be aware of the potential risk to their drinking water had their city utility not voluntarily started testing for PFAS in 2020. Utilities manager Lane Berg said the city wanted to be proactive about PFAS as momentum grows to regulate the chemicals at both the state and federal levels.

In October, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency announced its intention to enforce new limits on certain PFAS in drinking water.

At the state level, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resource’s PFAS Action Council has been coordinating the state’s response, including identifying contaminated sites and developing potential regulations, since late 2019. During a Nov. 10 meeting of the council, policy director for the DNR’s office of emerging contaminants Mimi Johnson said she expected the agency to present a set of drinking water standards to the Natural Resources Board as early as January 2022.

The city of Eau Claire has identified PFAS contamination in nearly half of its municipal wells at different points, and after detecting PFAS contamination, is regularly testing its water supply while employing other mitigation strategies to keep these “forever chemicals” out of its drinking water. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

How forthcoming standards might be enforced remains unsettled. Meanwhile, as a regulatory framework for PFAS takes shape, many utilities in Wisconsin may be ill-prepared to act on them.

In 2019, the DNR sent a letter to 125 public utilities across Wisconsin asking them to begin screening for PFAS in wastewater. The request was non-binding, and the vast majority of utilities decided not to begin testing. Eau Claire was among a handful that opted to do so, and it began sampling its drinking water around the same time.

Testing for PFAS “is really time consuming and expensive,” said Christy Remucal, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Remucal studies how PFAS chemicals travel through the environment and how they break down — or don’t.

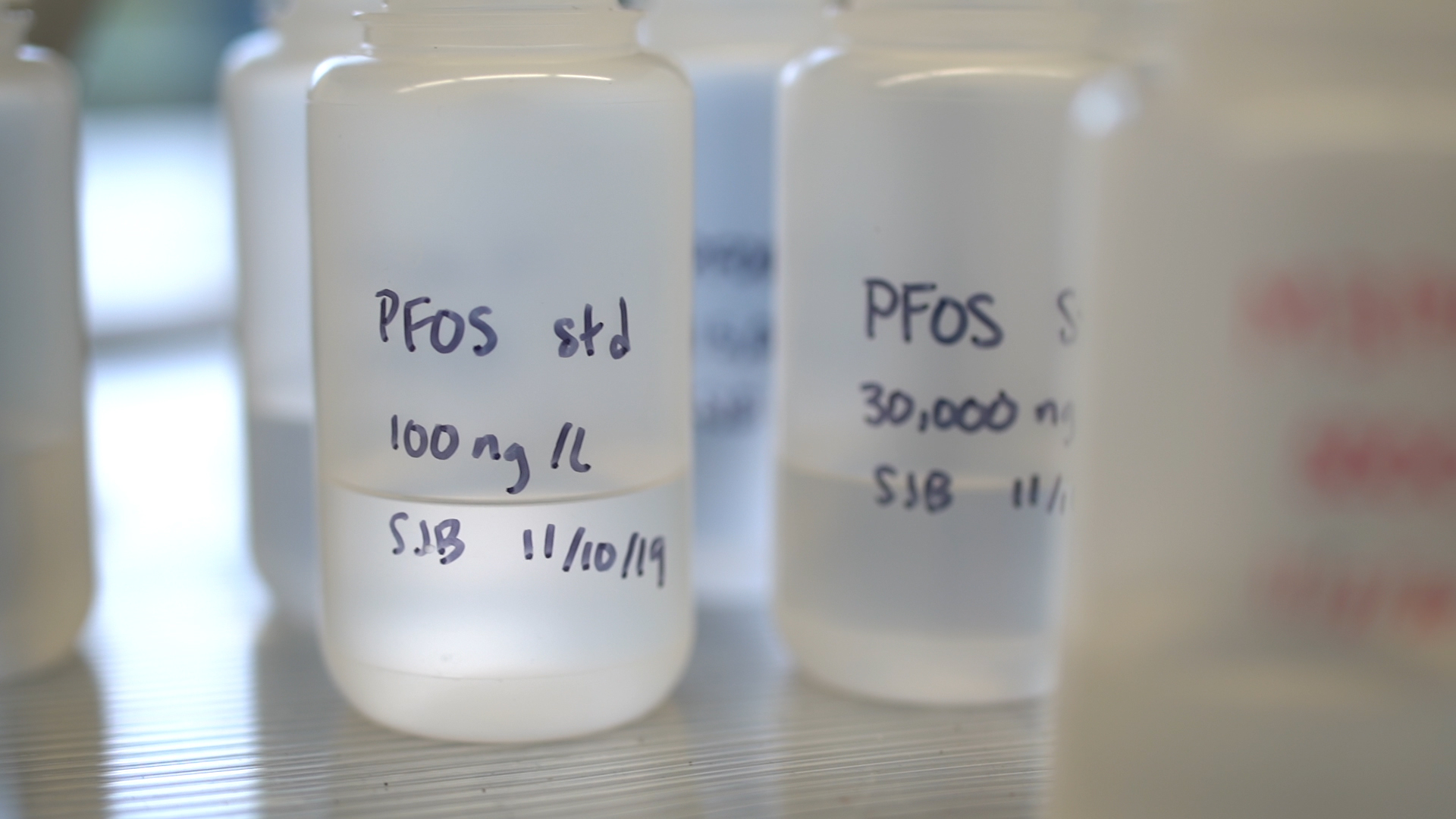

It costs hundreds of dollars to analyze just one water sample for PFAS, Remucal explained. The Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene lists prices between $375 and $425 per sample, depending on the number of PFAS chemicals being tested.

“There’s a lot of reasons for that,” she said. “One of the big limiting factors is that there’s a lot of prep that goes from taking your water sample into something you can actually analyze … and that’s actually really labor intensive.”

Christy Remucal (center) is an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at UW-Madison, and researches how and where PFAS is found and moves through Wisconsin’s waters. (Credit: Courtesy of Bonnie Willison / Wisconsin Sea Grant)

The lab instruments required to analyze samples are also costly, in part because they need to be able to detect extremely miniscule PFAS quantities. Hazardous PFAS levels are measured in parts per trillion, compared to parts per billion for other types of contaminants like arsenic.

On top of these already high costs, as of November 2021 the city of Eau Claire pays a premium to ship biweekly samples to a laboratory in California that specializes in PFAS sampling and offers next-day results. The utility ships three samples — two of its treated drinking water and one from the water entering an artificial pond — for the expedited analysis every other week at a cost of $1,000 per sample. It has three to four more well samples analyzed every week for $400 each.

“It’s expensive, but it’s something that we’re going to continue to do, and we’re using that information to dictate how we respond,” said Berg.

A vexing set of contaminants

Eau Claire’s decision to shut off the four wells was voluntary, even as the DNR continues to develop PFAS drinking water standards based on the state health department’s recommendations.

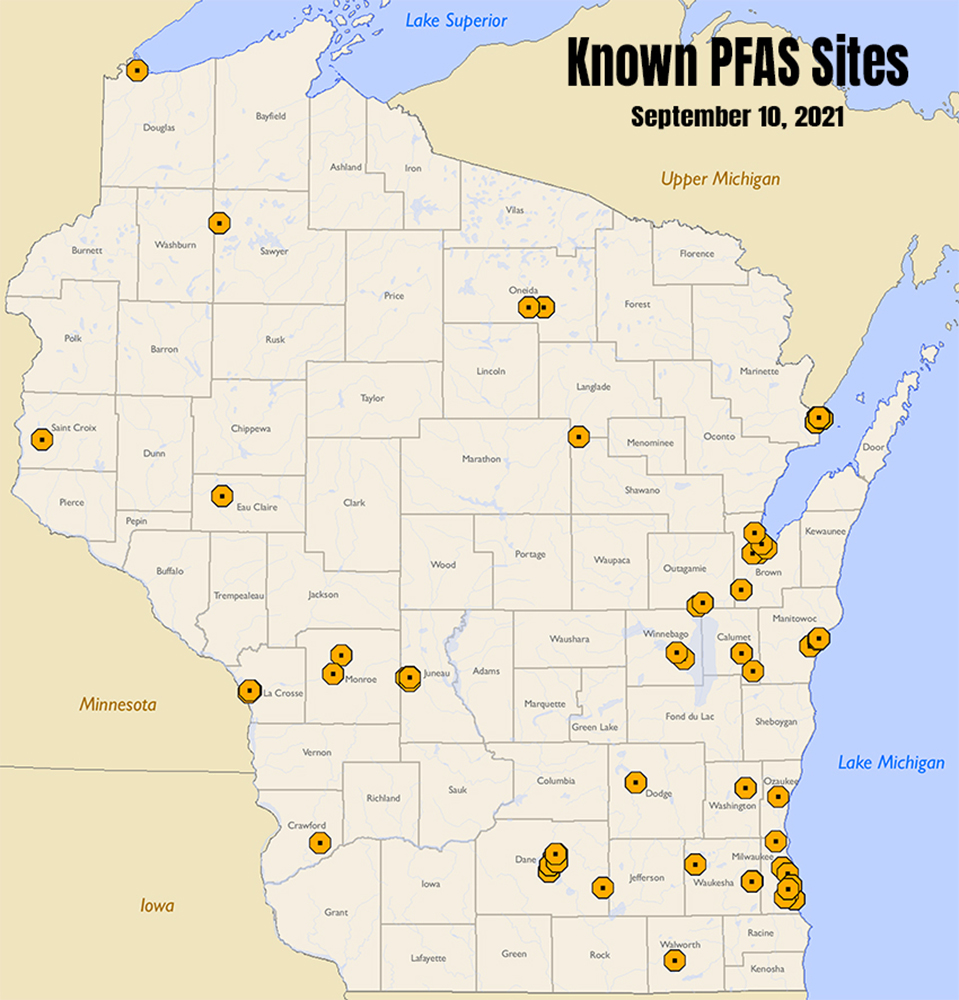

PFAS is a growing problem in water-rich Wisconsin. Sites of major contamination have cropped up around the state. They’re often located near airports or testing facilities where PFAS-laden firefighting foams have long been used. These sites include French Island near La Crosse, multiple areas in and near Madison and a region around Marinette and Peshtigo. In all, the DNR had listed more than 50 sites across 23 counties with known PFAS contamination as of September 2021.

Places where PFAS contamination has been identified are found across Wisconsin, with more than 50 individual sites identified as of Sept. 10, 2021. (Credit: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources)

In Eau Claire, utility officials emphasized that they have never found hazardous PFAS levels in the drinking water leaving the city’s treatment facility.

At the same time, Eau Claire utilities manager Lane Berg said since testing for PFAS started in 2020, he’s learned just how vexing of a contaminant it can be.

Eau Claire officials did not think shutting off the four contaminated wells would be a problem because the remaining wells were more than capable of providing enough safe drinking water for the city’s roughly 70,000 residents, Berg said.

But as the utility continued testing wells that were still operating, it made a concerning discovery: PFAS levels were creeping up in three additional wells adjacent to the ones that had been shut off. The utility decided to stop using those wells too.

Keeping all seven wells shut down indefinitely, however, could risk PFAS migrating farther through the groundwater to even more wells within the utility’s 400-acre wellfield beside the Chippewa River.

In consultation with the DNR, the city came up with a temporary fix. It rehabilitated an old detention pond between the wellfield and the river, and in September began pumping water from three of the contaminated wells and routed it into the pond. The water entering this pond is one of the three sources the city has tested every other week along with the weekly well tests. Instead of flowing into the utility’s treatment facility, the contaminated water now sits in the pond before eventually seeping back into the aquifer near where it originated.

City of Eau Claire Utilities is pumping water from municipal wells where PFAS contamination has been identified into an artificial pond as a temporary way to keep it out of the drinking water treatment process. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

The approach seems to be working, for now.

“It’s very early, but we’re seeing positive results,” Berg said, noting that PFAS levels in five operational wells have since fallen.

A statewide situation

While expensive testing can identify concerning levels of contamination and keep track of progress in remediating PFAS, it’s far from the only expense communities might encounter as they begin to look for and control PFAS in drinking water.

As Eau Claire has discovered, even temporary remediation can come with a hefty price tag. Even with tens of thousands of dollars sunk into its system of diverting contaminated water, Lane Berg said the city utility is awaiting the results of a costly groundwater study before developing a permanent fix.

A growing number of utilities in Wisconsin are beginning to test their drinking water for PFAS, especially those that draw from sources near facilities like airports that have a high risk of contamination. The DNR has identified firefighting foams used at the nearby Chippewa Valley Regional Airport as a possible source of the contamination in Eau Claire.

Elsewhere around the state, testing has identified PFAS in municipal wells in La Crosse, Madison, Rhinelander and West Bend, though not at levels that are understood to threaten drinking water safety.

The amount of PFAS assessed to be hazardous can be miniscule, at the level of parts per trillion in the environment, compared to pollutants like arsenic, which can be thousands times more common. (Credit: Courtesy of Bonnie Willison / Wisconsin Sea Grant)

UW-Madison engineering professor Christy Remucal said she’s glad to see more utilities looking for PFAS in their drinking water despite the costs.

“It’s really good that some utilities are being proactive and looking for these chemicals,” she said. “Anything we can do to limit human exposure is really important.”

She wasn’t surprised to hear about the contamination found in Eau Claire.

“I think every other week I see a new site in Wisconsin or around the country that has PFAS contamination,” Remucal said. “I think the more that we test for it, the more we will find it.”

Berg agreed.

“As we go on here, we’re going to see that [PFAS] are in a lot more areas than are identified already,” he said. “I think we’ll see it throughout the state.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us