How Wisconsin's Wolf Hunt Quotas May Prompt Federal Review

Whether or not wolves remain off the federal endangered species list or receive renewed protections is based on their numbers in the upper Midwest, and DNR policies are set to cut deep into the state's population of the species.

By Will Cushman

August 30, 2021

A wolf reacts to a noise behind it in this image from a trail camera placed on the reservation of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa over the winter of 2016-2017. (Credit: Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa)

Following decades of steady growth, Wisconsin’s gray wolf population faces an unclear future after losing federal protections under the Endangered Species Act.

These uncertainties are in part because — unlike in neighboring Michigan and Minnesota — state law mandates that whenever the animal does not appear on a federal or Wisconsin list of endangered species, the state must hold an annual wolf hunt.

With a majority of the current seated appointees to the Wisconsin Natural Resources Board tasked with setting the parameters of these hunts favoring relatively high harvest quotas, about half of the roughly 1,050 wolves that were estimated to be in the state in 2020 will have likely disappeared from the landscape before the end of 2021.

The trajectory of Wisconsin’s wolf population may help determine whether the species stays off the endangered species list for good. Advocates say actions by the Natural Resources Board, which sets policy for the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, could prompt a federal review of the state’s wolf management and provide a basis for returning the animals to federally protected status.

But the post-delisting plan by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, along with political dynamics between state and federal agencies, may serve as roadblocks to any potential review or relisting based on Wisconsin authorities’ management decisions.

“This is an overly aggressive control on the wolf population,” said Adrian Wydeven, a former wolf biologist for the DNR, speaking about the board’s Aug. 11 decision to allow hunters to kill up to 300 wolves during a hunt planned for November 2021.

The November harvest quota is more than double the 130 wolves that DNR scientists recommended. It comes after more than 200 wolves were killed in February during the state’s first wolf season since delisting.

Wydeven retired from the DNR in 2014 and now volunteers for Wisconsin’s Green Fire. The conservation group has emerged as a vocal critic of Wisconsin’s wolf management since the species was delisted.

In April, the group published a report criticizing the DNR’s handling of the February wolf hunt, during which state-licensed hunters reported killing 218 wolves. That’s about 100 more than they were allotted out of a total quota of 200 wolves split between tribal members and state-licensed hunters. Tribal communities chose not to issue licenses for their allotted quota of 81 and decried the process leading to the hunt.

The February hunt followed an abbreviated and chaotic planning period. The DNR originally sought to wait until November to hold its first wolf hunt since the federal delisting. Around the same time that environmental groups filed a federal lawsuit to halt the delisting, the state’s plans were derailed in late January when a Jefferson County judge ruled in favor of a Kansas-based hunting advocacy group that had sued the DNR and ordered the agency to hold a hunt before then end of February. A state appeals court subsequently upheld that ruling.

The April report published by Wisconsin’s Green Fire highlighted what the organization described as “multiple failures” in the state’s management of that hunt. Its criticisms included what the group characterized as a lack of meaningful consultation with tribal partners and the timing of the hunt during the wolves’ breeding season.

The report estimated that the killing of pregnant females and alpha males during breeding season could result in anywhere from 60 to 100 of the state’s 245 known wolf packs producing zero pups in 2021. Wolves’ complex biology and social structure make it particularly difficult for researchers to assess the immediate impact of a hunt during breeding season, though, which the group pointed to as one of several reasons to set a cautious harvest quota for the next hunt.

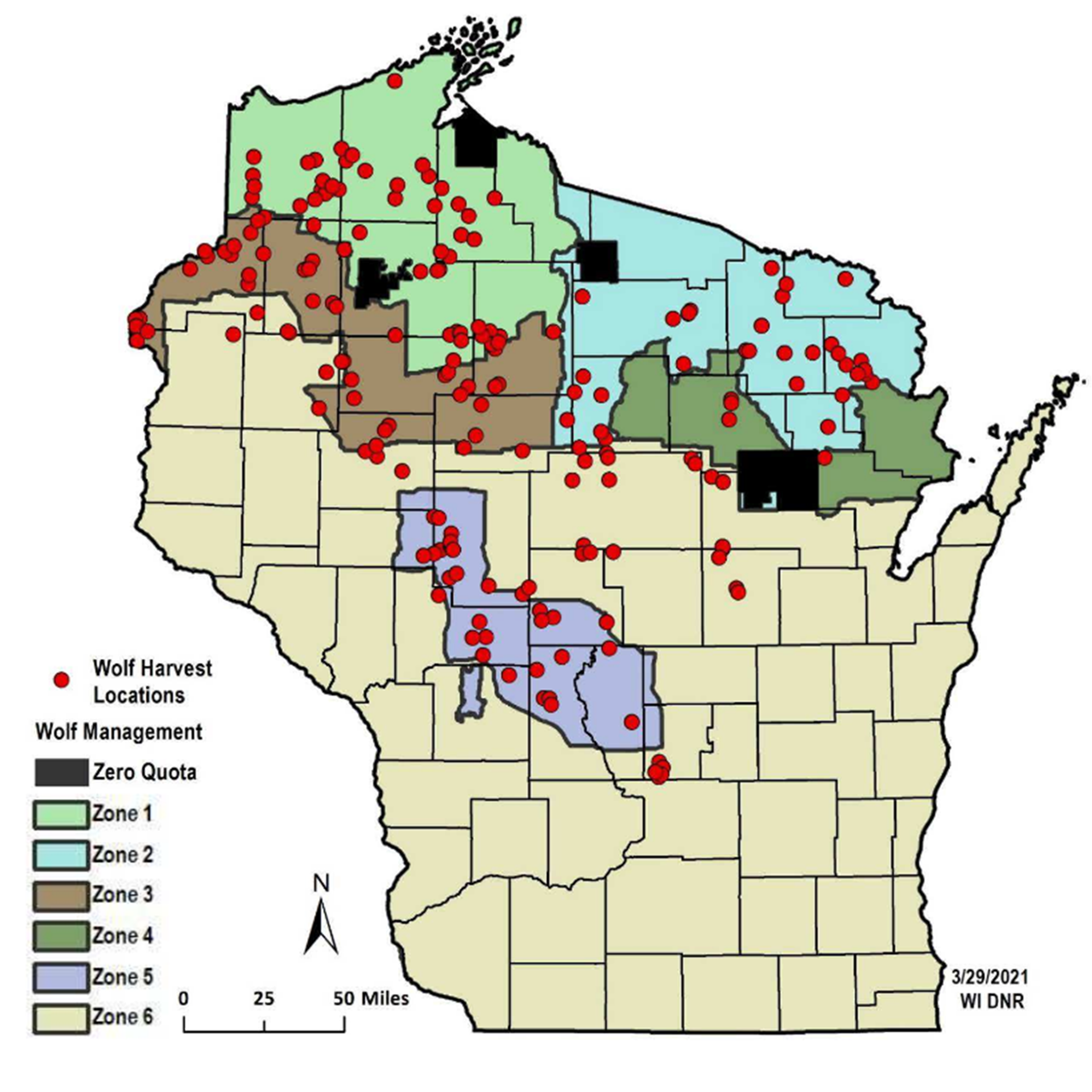

A map of Wisconsin’s wolf management zones shows the locations (red circles) where wolves were killed during Wisconsin’s February 2021 wolf hunt. (Credit: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources)

Instead, the Natural Resources Board, chaired by an appointee of former Gov. Scott Walker who has refused to vacate the seat after his term expired in May and is being sued by the state Attorney General, opted for a quota that far exceeded the recommendation of the DNR’s own scientists. The decision, Wydeven asserted in a Wisconsin’s Green Fire statement, “would likely have a destabilizing effect on almost every wolf pack in the state” and make a review of state management by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service “highly likely.”

In an email, a spokesperson for the DNR declined to comment for this story.

The federal agency is bound by law to monitor the population of any species it removes from the endangered species list for five years. In an email, a U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service spokesperson indicated the agency would assess the impacts of the February 2021 hunt and future hunts over the five-year period via annual population monitoring data provided by the DNR and tribes. If the data show the population falling significantly, the service would likely investigate to decide whether to propose a relisting or, if warranted, an emergency relisting, the spokesperson explained.

Wydeven said the agency’s post-delisting monitoring plan for wolves in Wisconsin, Minnesota and Michigan provides reason to believe that Wisconsin’s management since it could merit a review by the agency.

Specifically, he pointed to a list of factors the agency said could indicate “a potential cause for concern.” These include “a rapid and large decline (for example 25% or more from the previous year) in the late winter wolf population estimate for Wisconsin or Michigan.” However, the agency’s plan states such a population decline, while a potential cause for concern, would not necessarily trigger any substantive federal action.

Further, the post-delisting plan notes several events that “might cause consideration of relisting or emergency relisting.” These include an extreme population decline — one that reduces the wolf population in Wisconsin to below 100 or the combined population in Wisconsin and Michigan to below 200. Such a decline “might be evidence of a serious problem, but by [itself] may not trigger Federal regulatory action,” according to the plan.

Indeed, a formal federal review of the state’s management is no sure bet, according to Dan Rohlf, a law professor at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon. Rohlf co-founded the university’s Earthrise Law Center, which provides legal services for nonprofit conservation organizations, and has argued a number of cases pertaining to enforcement of the Endangered Species Act.

Rohlf said the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service is likely to closely follow wolf management in Wisconsin in particular because the species’ recovery in the upper Midwest was specifically cited in the agency’s rationale for delisting wolves.

“The delisting notice is very clear that wolves have to be doing well in Minnesota and Wisconsin for the species to continue to be delisted,” Rohlf said. “If I were talking to officials in Wisconsin, I’d say, ‘You know, you’re playing with fire a little bit here because, yeah, wolves got delisted, but basically wolves got delisted across the country depending on what you do.'”

At the same time, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service under the Biden administration is likely not as wolf-hunting friendly as the one that delisted wolves under the Trump administration, Rohlf said.

“That, in my view, should send a message to the state that you are appropriately being placed under a microscope, and so your wolf management better be science-driven,” he said.

Still, Rohlf and others did not think there would be political willpower at the federal level to aggressively assert its powers in the form of an immediate reconsideration of its delisting decision or an emergency relisting. In May, the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission, a treaty rights group representing 11 Ojibwe tribes in Wisconsin, Minnesota and Michigan, sent a letter to the Midwest director of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service requesting the agency reconsider its decision to delist wolves in light of the February wolf hunt. A group of more than 100 scientists sent a separate letter with an identical request to the Biden administration. The treaty rights group has also objected to the DNR’s quota for the November hunt.

An emergency relisting “would basically be saying, ‘OK, states, we don’t have any confidence in you. We think you’re really screwing up,'” Rohlf said. “It would be a significant slap in the face to the states, and so just from a political standpoint, I think even the Biden administration is somewhat hesitant to do that.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us