Why is Madison considered a climate haven going forward?

Madison, Wisconsin and the Great Lakes region are increasingly touted as a refuge from impacts of climate change, but extreme weather, housing shortages and other issues loom as more people move.

By Hannah Ritvo | Here & Now

May 17, 2024 • South Central Region

“The August that we left, it was so dry and so hot that there were wildfires actually encroaching on Austin as we were leaving,” Jessica Mederson said. “As we were driving down the highway, it was literally just scorched, black earth.”

Jessica Mederson left Texas in 2012 to escape the heat.

“Everybody in the world wants to be in Austin. And I loved it a lot — but I hated the heat,” she added.

Mederson is among many who have left their homes to adapt to a changing climate. Over 3 million Americans have already moved due to climate change.

“If you look at the U.S. alone, last year, there had been $1 billion weather disasters almost every two weeks on average,” said Sumudu Atapattu, director of the Human Rights Program at UW-Madison and a professor at the University of Wisconsin Law School

Some of these migrants could be headed to places called climate havens.

“A climate haven is the idea of a place that’s a refuge or a safe spot from the impacts of climate change,” said Steve Vavrus, the state climatologist and co-director of the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts.

Madison is routinely cited as one of six climate havens around the United States, along with Wisconsin and the Great Lakes region on a broader basis.

“It’s been hypothesized that this area of the country could be a climate haven, because it might escape the worst of climate change impacts,” he said.

“Maybe just as important is what we don’t have — we don’t have hurricanes, we don’t have big wildfires, and we are far away from sea level rise,” Vavrus explained. “So, the combination of those things has made a lot of people speculate that our region of the country could be very attractive to so-called climate migrants.”

But it’s not all sunshine and rainbows.

Vavrus said potential climate migrants should be aware of Madison’s own increasing climate extremes.

“We get a lot of heavy rainfalls. We get a lot of flooding. We often get heat waves, too, that are hot and humid. And then last summer, we had so much wildfire smoke, and that caught people off guard,” he noted.

The 2010s were Wisconsin’s wettest decade on record by far.

“We had a lot of flooding events across the state in that decade,” Vavrus said. “And one of the worst, maybe the worst in that decade was in 2018, in August in Dane County, where just about a foot of rain fell in 24 hours, which was a statewide record. It’s an incredible amount of rain. It’s more like hurricane amounts, and it certainly caused terrible flooding. It even caused one fatality.”

Vavrus said the concept of climate havens started building steam in the late 2010s.

“This is something that I don’t think scientists anticipated would draw so much public interest,” he said. “It’s something that was really kind of a groundswell of interest from the masses. And that’s caught the attention of a lot of climatologists.”

It’s a debated notion, because there are many reasons that people move.

“The cost of living, the quality of education, the availability of housing — this is a big issue in Madison with high house prices and rents,” noted Vavrus.

And not everyone can escape disaster.

“There are communities who are unable to move due to poverty or social norms or disability or age,” Atapattu said.

“We have a history of locating polluting industries in low-income and minority communities. The environmental justice movement started as a result of that. These are the same communities that are disproportionately affected by climate change,” she explained. “I look at the link between human rights and environmental issues, especially climate change.”

Atapattu said there is anecdotal evidence that individuals are moving to Madison due to the impacts of climate change, but there isn’t enough data yet to truly know.

Nonetheless, climate migration is already happening around the world.

“Some communities are being relocated as we speak. Some communities — awaiting relocation,” she said. “And people are moving.”

Atapattu said climate change is a global problem with local impacts.

“It’s important for us to realize that the decisions we take will have repercussions thousands of miles away,” she said. “Small island states and people who are living there — they will be the ground zero of climate change, because they might lose everything they have, including their country. So, we don’t really know where those people will go and what will happen to those countries.”

Atapattu said the most important thing people can do is educate themselves, and prepare sufficiently for disasters and migration.

Cities — especially those deemed climate havens — must be ready to accommodate an influx of potential climate migrants.

Experts estimate more than one billion people could be displaced in the next 25 years due to changing weather.

“Can their infrastructure handle a lot more people? These are things that communities need to be thinking about,” Vavrus said.

Some cities have already begun promoting themselves as climate havens, particularly one in New York state and another in Minnesota.

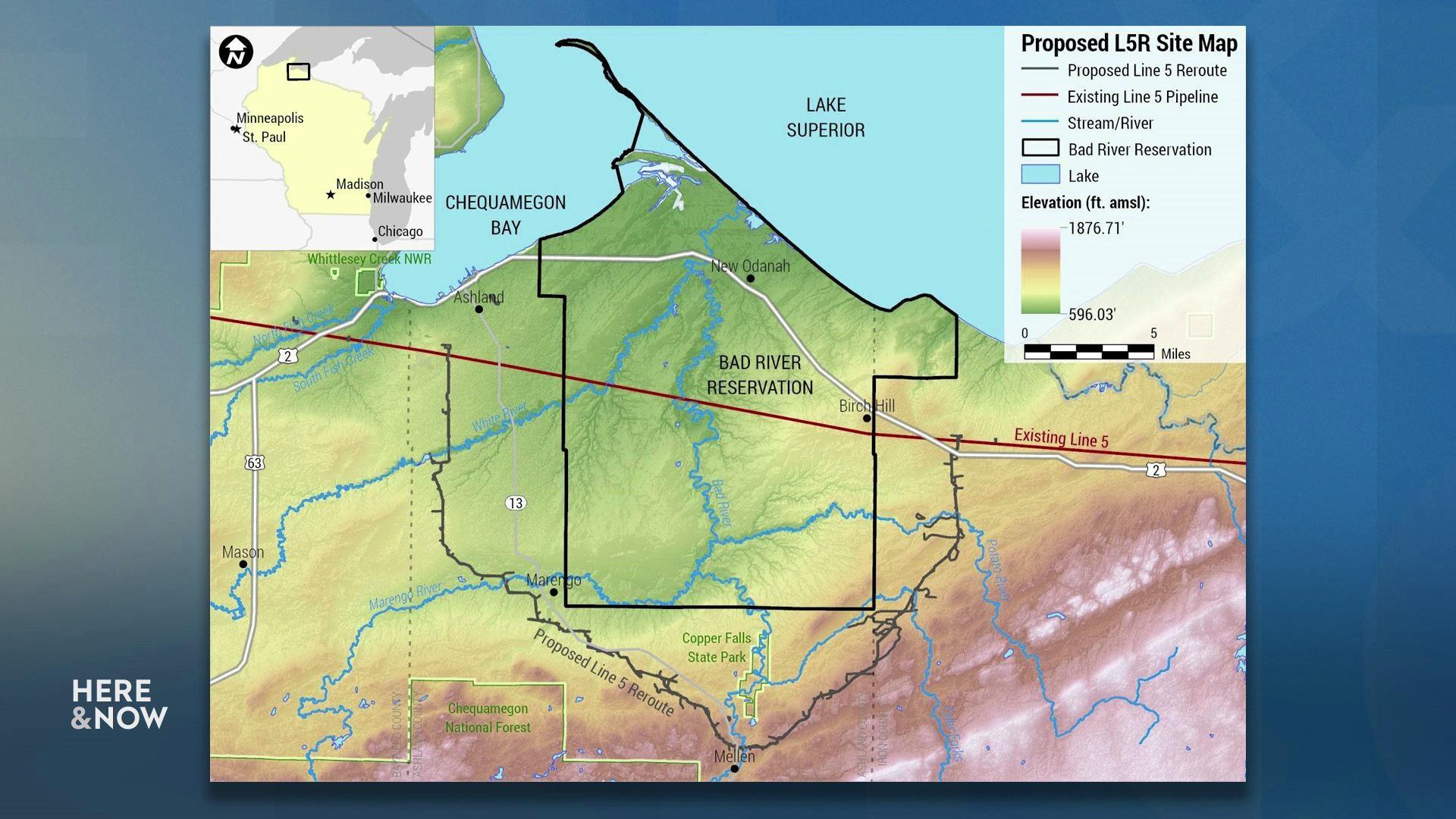

“Buffalo and Duluth are two communities that have gone all in with advertising and encouraging people to come to their communities, and hopefully they have the ability to take in a lot of residents fairly quickly,” he noted.

Madison hasn’t promoted itself that way, but Vavrus said it is important the city gets ready for potential climate migrants, as it’s clear the Midwest may be more immune to severe climate impacts than other regions.

“But again, people need to recognize that we’ve got our own challenges when it comes to climate and extreme weather here, too,” warned Vavrus. “There’s really no safe place from the impacts of climate change.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us