What to do about aging dams in Wisconsin's Driftless Area?

Extreme weather and limited budgets are central to plans for removing a series of earthen dams in southwest Wisconsin, but local residents are concerned about the consequences to their communities.

By Nathan Denzin | Here & Now

November 20, 2024 • Southwest Region

In the summer of 2018, Wisconsin’s Driftless Area was hit by massive and destructive storms.

“They were good ones. They were really dandy,” Christiana resident Dean Daniels said.

“If you were standing on top of the dam, which is about 39 feet above the valley floor, your boots would have been in water,” said Bob Micheel, who lives in Monroe County.

“The cleanup took well over six months,” Christiana resident Charlie Burke said.

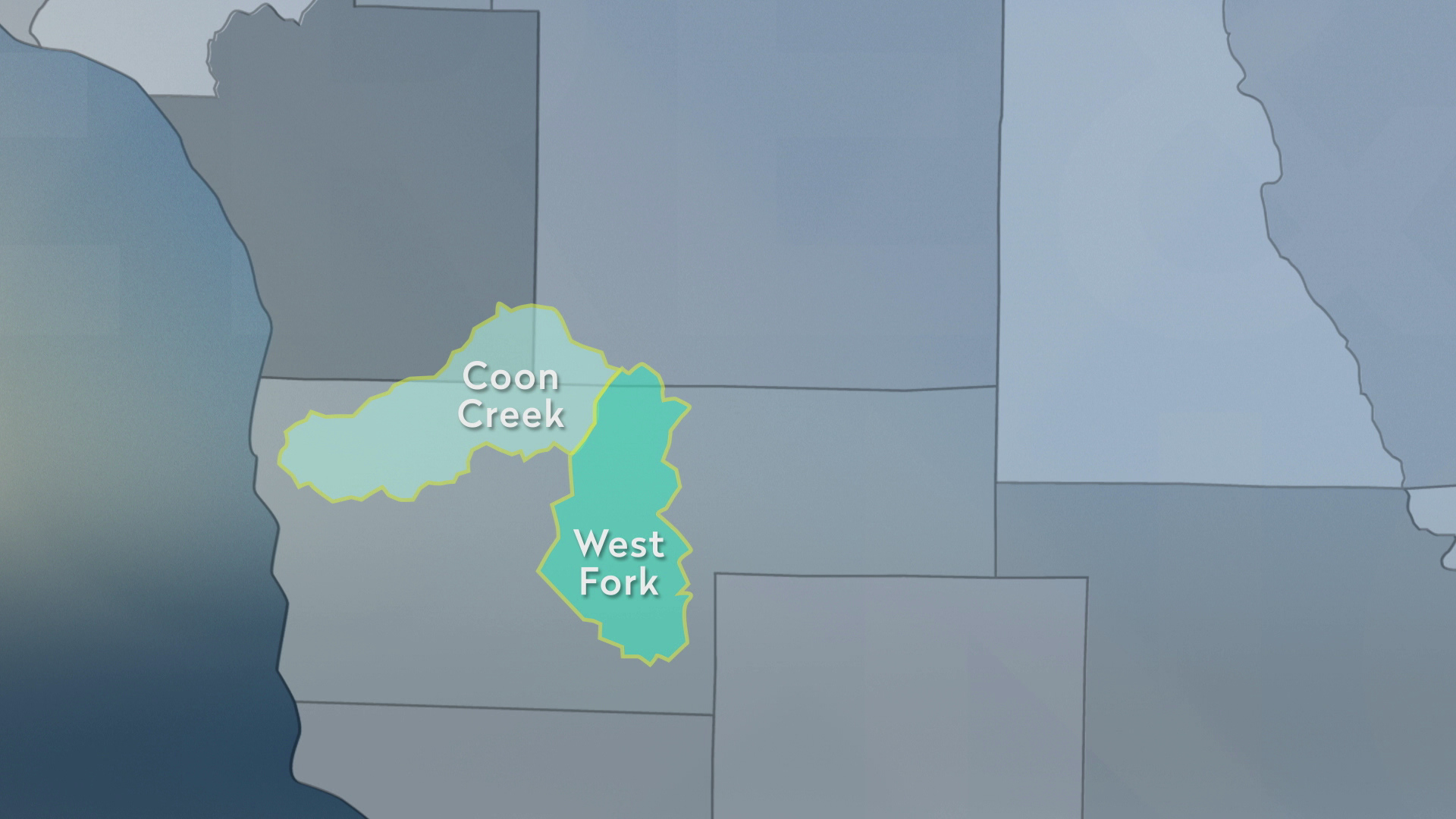

The storms caused dams to fail in the Coon Creek and West Fork Kickapoo watersheds near Viroqua.

“There’s over 10,000 structures in the United States — five structures breached in one event in 2018. That never happened before,” said Micheel, who is director of the Monroe County Land Conservation Department, which is in charge of dams in the Coon Creek watershed.

A map shows the outlines of the Coon Creek and West Fork watersheds, which were impacted by storms in 2018, in western Wisconsin’s Driftless Area. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Somehow, no human lives were lost in 2018, but roads were washed away and debris spread for miles.

“If you have a structure that fails, it’s like a giant bulldozer racing down the valley floor, destroying everything in its path,” Micheel said.

There are 23 earthen dams between the two watersheds that to the untrained eye look like big dirt hills. They are all past their 50-year expected lifespan, and climate change has supercharged storms the dams were never designed to hold back.

“We have 11 more structures that are still standing. The potential of that happening again is still there,” said Micheel.

Monroe County commissioned a study along with neighboring counties and both state and federal officials to figure out what the future of the dams might look like. This study considered nine options, including rebuilding or repairing, but in the end found removal was the only viable solution.

If they are taken out, it would be the largest dam removal project in the history of the United States.

“I was actually dumbfounded that there would even be a discussion about taking these dams out,” said Dave Eggen, a resident of Christiana. “They’ve saved this community and this valley from flash flooding now for nearly 60 years.”

Eggen is a retired farmer and a representative on the Vernon County Board of Supervisors, who has lived most of his life within a mile of at least six dams.

Despite these aging dams and threat of more dam failures, residents still say they still play a critical role in reducing flood events. They worry that removing them would mean multiple floods a year, hurting farming operations.

“There is no protection from flash flooding like a 30-foot-high earthen dam,” Eggen said.

Dave Eggen, a supervisor on the Vernon County Board, discusses his reaction to plans for dam removal project in the Driftless Area on Oct. 30, 2024. “I was actually dumbfounded that there would even be a discussion about taking these dams out,” said Eggen. “They’ve saved this community and this valley from flash flooding now for nearly 60 years.” (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

His neighbors agree.

“I have a concern over what will happen to our farming operation,” said Burke.

“What scares me the most is, you know, how are we going to have to react when the dam is gone?” asked Daniels.

“Bottom line is, I don’t see what the benefit really is,” Monroe County resident Mark Andrews said.

Eggen recalled a story from his grandfather, who had farmed the valley before the dams were built.

“After five years of farming out here on these fields, he realized that he wasn’t going to make a living farming in this valley because of the constant flash flooding,” Eggen said.

But the cost to repair or replace these dams is steep, estimated at about $61 million — removing them would only cost about $4 million.

“Vernon County doesn’t have the financial resources to operate, maintain and repair dams,” said Mark Erickson, who is the Vernon County resource conservationist, has been overseeing one dam that’s already in the process of being removed.

“Where that clay meets these sandstone abutments are hillsides — that’s proven to be the weak point,” Erickson explained.

All of the old dams in the area were connected to sandstone underneath hillsides, but over time that sandstone will crack and the dam could breach.

“You’ve seen one structure, you’ve seen them all because they breached the same way,” said Micheel.

Bob Micheel, director of the Monroe County Land Conservation Department, discusses the impacts of the Driftless Area’s aging dams on Oct. 30, 2024. “If you were standing on top of the dam, which is about 39 feet above the valley floor, your boots would have been in water,” said Micheel. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

If they breach, a violent burst of water would be released downstream with huge destructive power.

Monroe, La Crosse and Vernon counties have all approved a plan to remove the dams. But it will take additional studies, consultation and grant applications before any earth is moved. That leaves about 18 months for Eggen and his allies to stress the importance of the dams, and provide viable alternatives to removal.

“I’m sensing a lot of sympathy towards these dams being taken out — with hardly any options” Eggen said.

He thinks that with the right material and a friendly contractor, repairing the dams might not be as expensive as initially thought.

“I personally talked with a general contractor in the county to give me a ballpark to dig down and put in new age plumbing — he said $200,000 to $250,000,” said Eggen.

But his frustration runs deeper than the ballpark figures noted in the study.

Cost-benefit ratios were calculated to determine if federal funding would be justified to repair the dams. That ratio concluded that not enough people and structures are downstream for those dollars to be released.

“Our country can spend $111 million on a missile and they’re shooting them off every day in the Middle East. But you can’t come up with a handful of millions of dollars to help restore lifesaving dams like we’re standing on,” Eggen said.

The one dam that did qualify for federal funding to be reconstructed only did so because it holds back a standing lake. That lake has been contaminated multiple times by manure run-off, though.

If the plans go forward and the dams are removed, the community knows it will have to change to survive future floods.

“The dams have definitely been a reckoning about how we live on this land,” said Sydney Widell.

“The biggest concern really is, ‘What are the next steps?'” asked Nancy Wedrick, a resident of Coon Valley.

Sydney Widell, at left, and Nancy Wedrick, at right, who are members of the Coon Creek Community Watershed Council, discuss the impacts of aging earthen dams on the community and plans to move forward on Oct. 10, 2024. “The biggest concern really is, ‘What are the next steps?’” asked Wedrick, (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Widell and Wedwick are members of the Coon Creek Community Watershed Council. Wedwick serves as president and Widell as watershed coordinator.

“We started to learn and find out that there are indeed many things that you can do just as people or as landowners to mitigate flooding, to slow water, to make running water walk,” Wedwick said.

The Coon Creek watershed is no stranger to first-of-its-kind interventions. In the 1930s, the federal government used this land to demonstrate the effectiveness of sustainable farming practices.

“Here we are again. What are we going to do next?” asked Wedwick.

The likely answer: return to many of the practices implemented in the 1930s.

“Building the terraces, returning to the contours strips and doing whatever we can to infiltrate good quality water,” Wedwick explained.

Terrace farms are up higher on ridges and build berms between strips of crops to slow water. She also mentioned the effectiveness of planting perennials, oats or even building more mini-dams — anything to build the quality of the soil and slow water down.

“There’s some levers that we have more control over than others, and it’s a matter of using the levers we have as effectively as possible,” Widell said.

But they noted this approach doesn’t address all issues.

“We should not think that, yes, by implementing a few practices, we’re going to solve problems of flooding. No, we are not. We can slow water and we can start a process,” Wedwick said.

A healthy ecosystem, Widell and Wedwick argue, will somewhat reduce the danger of smaller floods.

“These smaller events — the two, five, 10, 25-year storm events — we can manage those. We can do that,” Micheel said. “But when we get these 100-year storm events every year, those are the ones we have to respect and stay out of harm’s way.”

Beyond the question of whether people will have to relocate from the valley floor, there are more concerns. Will sediment from recently decommissioned dams get washed downstream? How will it affect the famous trout streams and fishery around Coon Creek? How will farms be impacted?

Jersey Valley Lake, as seen on Oct. 29, 2024, has been contaminated in the past by manure runoff and as a result, the dam has qualified for federal funding. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

There aren’t easy answers for each question, but these communities will have to grapple with them over the coming months.

“For the people that are living and using those buildings, that’s their livelihood,” Eggen said.

“This is the most important work I have ever done, or will ever, ever do,” Wedwick said.

Editor’s note: This report is corrected to clarify references to the federal regulatory status of dams in the Coon Creek watershed.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us