Speeding cleanup of pollution at 'Areas of Concern' on Wisconsin's waterways

One target of the 2021 federal infrastructure package is a decades-long effort to remediate industrial contamination in five locations in the state where rivers and estuaries flow into the Great Lakes — conservationists are hopeful the funding will accelerate this restoration process.

By Will Cushman

March 8, 2022 • Northern Region

Clean sediment dredged from the St. Louis River estuary between Superior, Wis. and Duluth, Minn. was used to rebuild an island in the estuary that provides critical habitat for rare shorebirds. Towering over the water is the Blatnik Bridge, a 61-year-old structure connecting the two cities. (Credit: Courtesy of J.F. Brennan Company via the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources)

The bipartisan federal infrastructure law passed in 2021 is set to not only invest in improvements to the nation’s roads, railways, airports and bridges, but also accelerate a decades-long cleanup of the most polluted places in the Great Lakes, including four sites in Wisconsin. A March 2 visit to Superior by President Joe Biden highlighted these connected priorities, which will be funded to the tune of billions of dollars over the next decade.

During his stop, Biden announced the infrastructure law would provide funds for reconstruction of the Blatnik Bridge, a 61-year-old span connecting Superior with Duluth, Minnesota. While the aging bridge serves as a transportation backbone of the region’s economy, the busy waterway it straddles is another target for infrastructure funding.

The natural estuary where the St. Louis River empties into Lake Superior has long been a center of industrial activity and pollution, which accumulated for more than a century. While most of the pollution has been halted in recent decades, harmful chemicals and other industrial byproducts linger in sediments and soils, with negative consequences for water quality, wildlife, local fisheries and tourism.

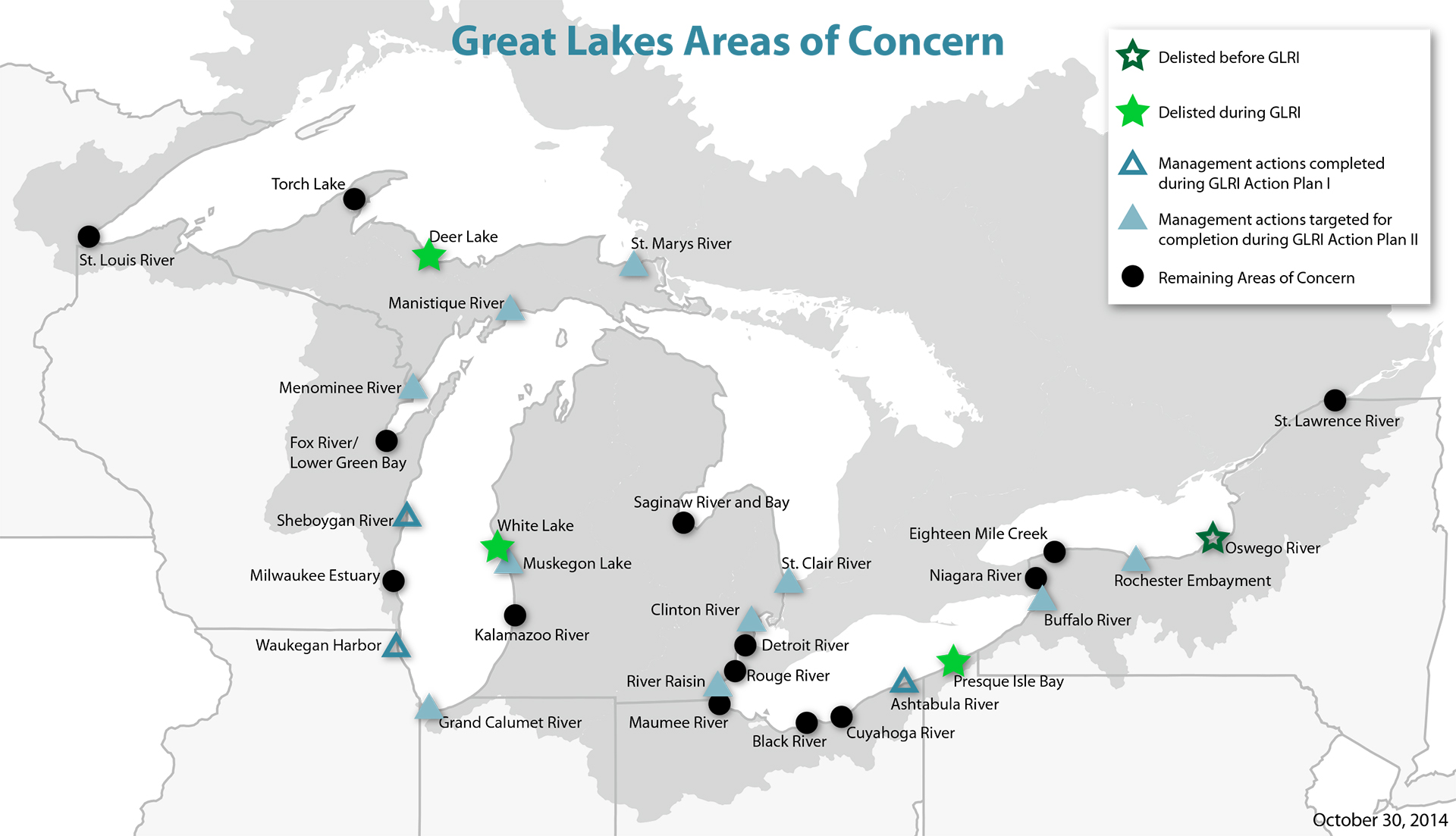

A legacy of pollution around the Twin Ports is not unique in the Great Lakes. In 1987, the United States and Canada identified dozens of sites where contamination posed an ongoing threat, dubbing them “Areas of Concern.” These include five sites in Wisconsin, each tracked by the Department of Natural Resources: the St. Louis River, the lower Menominee River, lower Green Bay and the Fox River, the Sheboygan River and harbor and the Milwaukee estuary. Pollution at these sites is extensive, and cleaning it up is a complex, time-consuming and expensive endeavor — over the past 35 years, the lower Menominee River is the only one of the five where cleanup has met its restoration goals.

Now, with $1 billion of the infrastructure law’s funding allocated toward accelerating the cleanup of the remaining Areas of Concern around the Great Lakes, the other four sites are slated to be restored by 2030. The funding builds on the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, which has boosted federal funds for cleaning and protecting the Great Lakes since 2010.

A 2022 map shows the status of Great Lakes “Areas of Concern” in the United States as of January 2022. There are five locations in Wisconsin, with different levels of status in terms of their management. (Courtesy of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency)

“This is a gamechanger,” said Steve Galarneau, program director for the DNR’s Office of Great Waters. The office oversees environmental cleanup and protection along Wisconsin’s Great Lakes and Mississippi River shorelines.

While cleaning up Areas of Concern has steadily progressed over the last decade, Galarneau said some of the most complex and expensive work remains to be done. In particular, he pointed to an enormous volume of sediment laden with heavy metals and harmful chemicals like PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) that still needs to be removed from all four sites. This includes more than 1.7 million cubic yards of contaminated sediment in the Milwaukee estuary, which encompasses stretches of the Milwaukee, Menomonee and Kinnickinnic rivers.

Polluted sediments are directly harmful to ecosystems and wildlife, but they also pose challenges for remaining manufacturers by reducing water depth and limiting navigational channels. Because some of the sediment is so toxic, restrictions on navigational dredging are in place, and dredging for cleanup purposes is tightly controlled.

“We are looking at some very big, complex issues with contaminated sediment,” Galarneau said. Not only does the sediment need to be removed via careful dredging, it then needs to be safely decontaminated and landfilled in a way so any lingering pollution doesn’t continue to pose a threat, he said. On top of that, the dredging is occurring in some of Wisconsin’s busiest waterways where boating traffic must be closely managed.

Galarneau said the new infrastructure funding would ultimately make dredging and other cleanup less expensive by speeding the process.

“In an area like Milwaukee, we would have been there year after year after year chipping away at the challenge,” he said. “This is going to allow us to go in there and decrease that impact on the community and see an economic and environmental recovery at a much greater rate.”

The Milwaukee estuary is perhaps the most daunting Area of Concern remaining in Wisconsin, but those involved in restoring other sites around the state targeted for funding welcomed the news as well.

An aerial view of the Kinnickinnic River and Port of Milwaukee, which make up part of the Milwaukee Estuary Area of Concern, shows an area where sampling and analysis of polluted underwater sediments was completed in 2020 to prepare for eventual dredging. (Credit: Courtesy of Sigma Group via the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources)

“It’s an incredibly positive thing for the Great Lakes and certainly for Green Bay,” said Mike Mushinksi, a conservationist for the Brown County Department of Land and Water Conservation. Significant progress has been made in recent years to restore the lower Green Bay and Fox River, including removal of more than 8 million cubic yards of sediment. Mushinksi said contaminated sediment continues to be “the big outstanding issue.”

In Superior, news of the additional funding came just a couple weeks before tribal members, scientists, environmentalists and industry representatives met to discuss ongoing research and restoration work happening within the St. Louis River watershed. Much of the work is aimed specifically at the Area of Concern centered around the Twin Ports.

The active restoration projects already amount to “a herculean effort happening right now,” said Deanna Erickson, director of the Lake Superior National Estuarine Research Reserve in Superior. The reserve is operated by the University of Wisconsin-Madison and is part of a federally-funded research network.

Erickson described the additional funding as simultaneously exciting and daunting.

“It’s almost like when the snow melts in spring and there’s a big pulse of water,” she said. “It’s both abundant and a lot to manage.”

Editor’s note: A caption for a photo accompanying this story was corrected to note an island in the St. Louis River estuary was rebuilt using clean sediment dredged from navigational channels.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us