Nelsonville's water woes: How nitrate contamination has consumed the community

Here & Now extra: Residents of a rural village in central Wisconsin are trying to ensure access to clean drinking water sources as they clamor for support from the state to address and mitigate the sources of nutrient pollution.

By Nathan Denzin | Here & Now

December 15, 2022 • West Central Region

(Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

When driving through Wisconsin, it’s easy to tell when farmers are spreading manure. The smell can drift for miles, even if it usually goes away after a few hours. However, certain chemicals that are in manure can linger in the environment for decades, including the commonplace nitrate.

Cash crops — like corn or alfalfa — need agricultural nutrients like nitrate to grow, but quickly suck up supplies that occur naturally in the soil. To restore that depletion, and to produce a maximum yield, farmers spray manure on fields to replace nitrates taken up by the previous year’s crops.

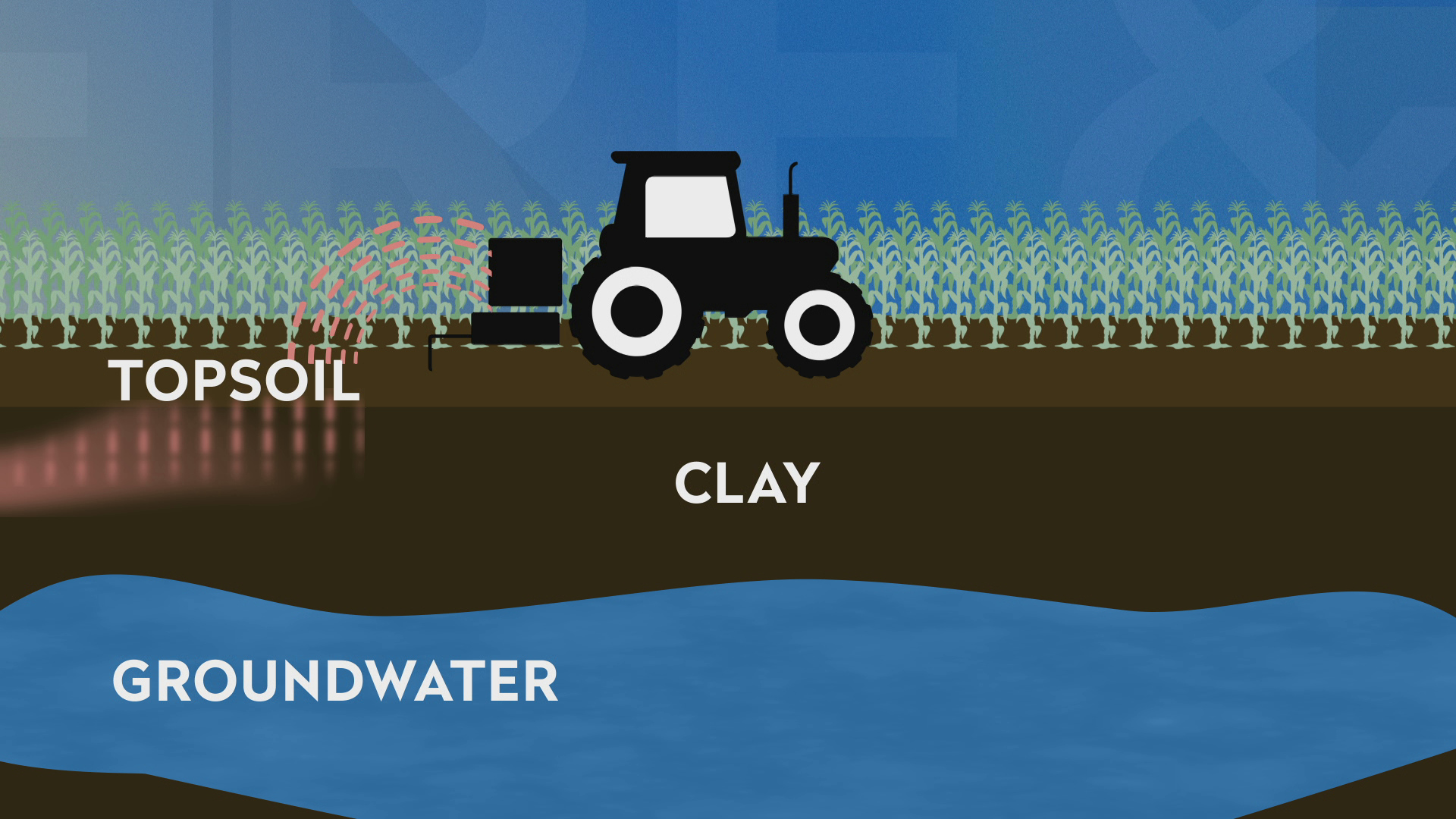

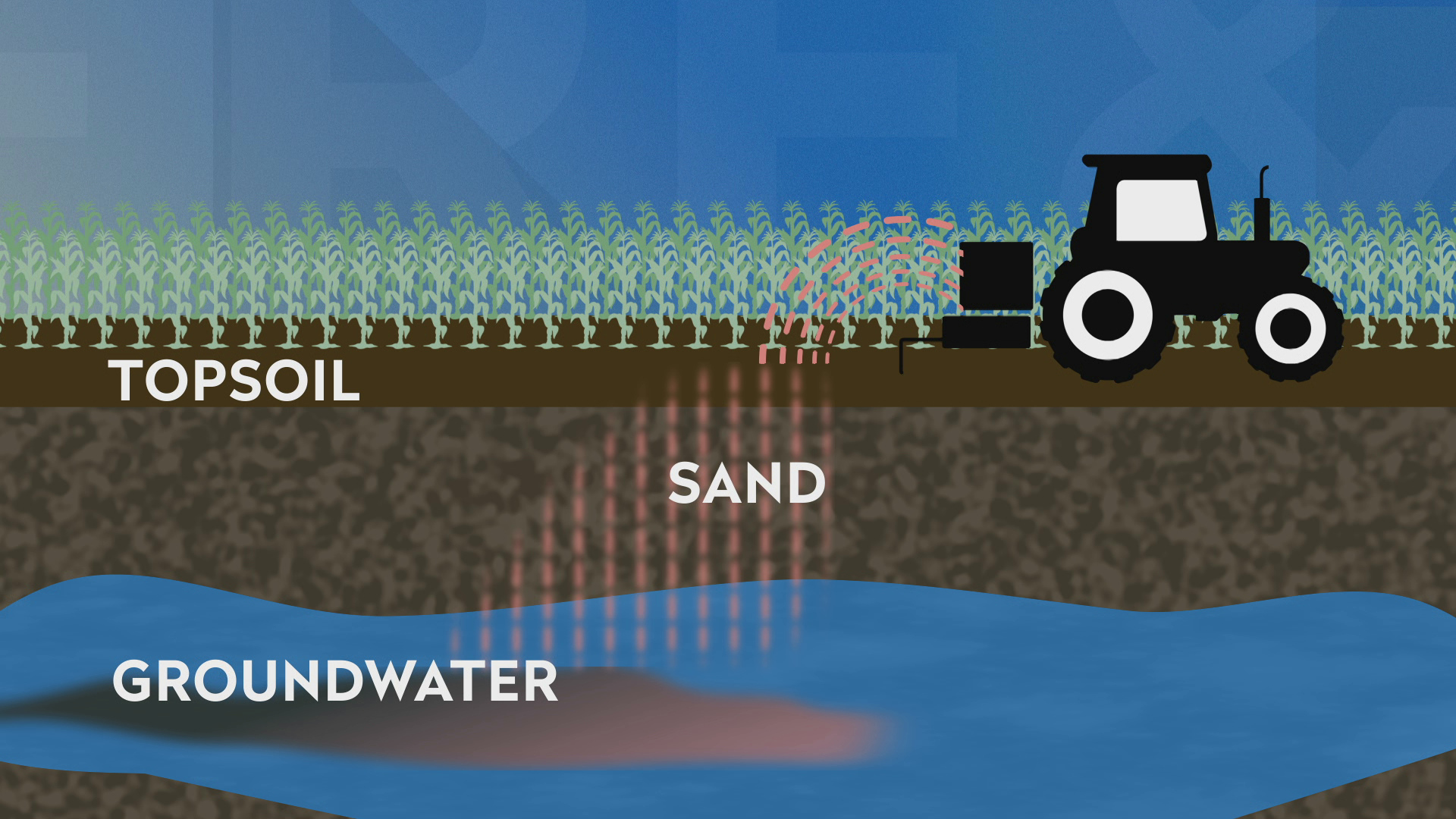

However, when a surplus of manure is sprayed on a field, nitrates will not be completely absorbed by growing crops, leaving more in the soil. Nitrate is a particularly slippery chemical that seeps downward through soil when it rains or when snow melts.

This process hasn’t been a problem in some of Wisconsin, where denser soils rich in clay are able to filter out nitrate before it can reach aquifers. However, in the state’s Central Sands region, the soil is much more sandy and does not filter out nitrates as effectively.

- An illustration shows how nitrate is less likely to infiltrate groundwater in clay rich soil. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

- An illustration shows how nitrate is more likely to infiltrate groundwater in sandy soil. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

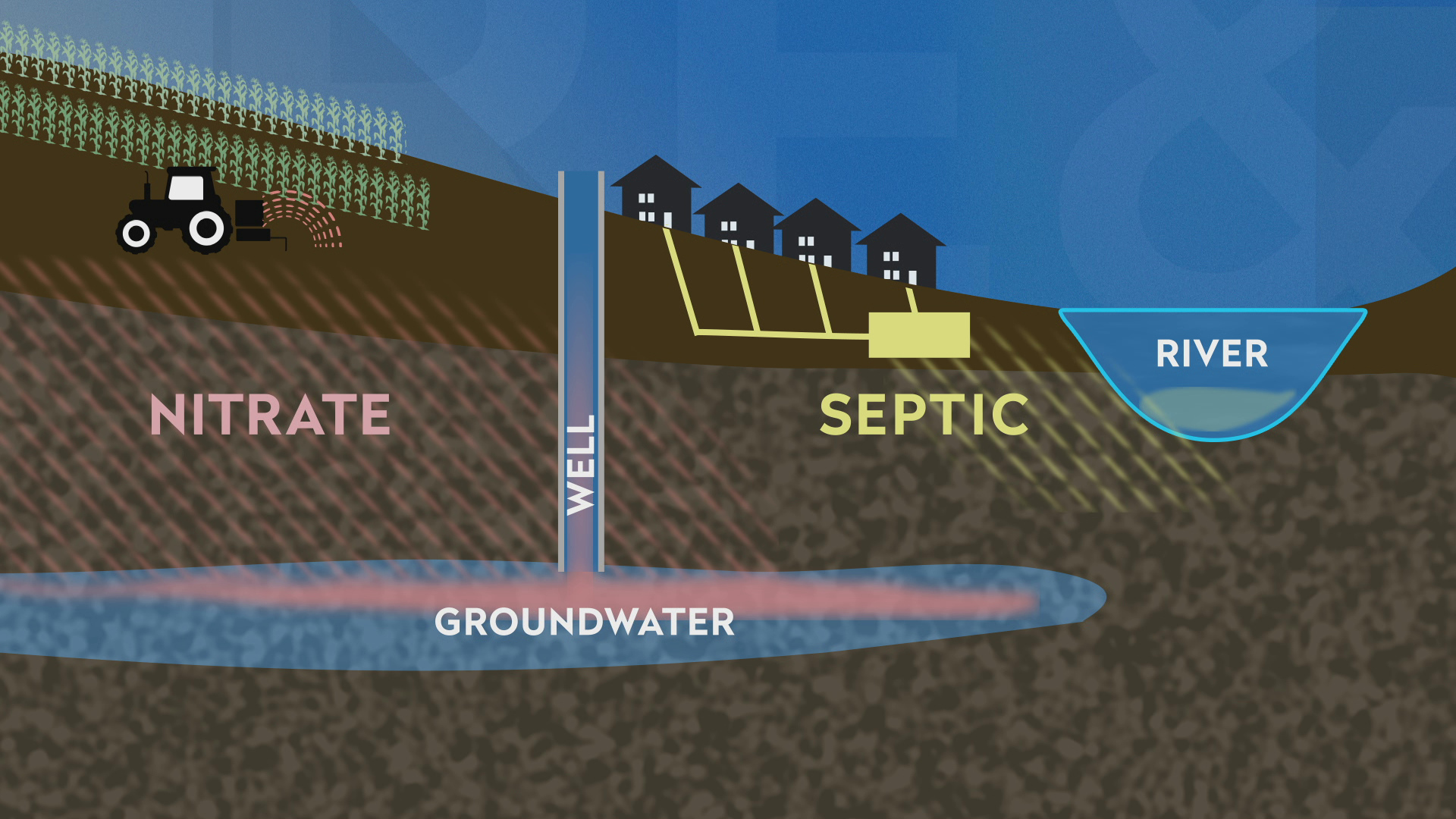

Eventually nitrate will seep down into aquifers deep underground, where this soluble chemical mixes with the freshwater. The results are tasteless, odorless and colorless.

Nitrate in aquifers can present a particular danger to those who get their drinking water from a private well, rather than a treated municipal water supply, and is a particular risk in rural areas. Private wells in Wisconsin are not monitored by government agencies, and responsibilities of maintenance and water quality testing falls on the well owner.

Research has found septic system waste doesn’t infiltrate deep enough in soil to contaminate to groundwater. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services warns high levels of nitrate in drinking water can cause birth defects, thyroid disease and increase the risk of colon cancer, among other health concerns. Any level above 10 parts per million can be harmful to long-term health.

A nitrate hotspot

Nelsonville is a small village with fewer than 200 residents in Portage County, and is located in the heart of the Central Sands region. The community has been dealing with a nitrate pollution problem in well water since 2018, though it’s likely excess nitrate has been present in the area’s groundwater for decades.

“[County officials] offered a nitrate screening in the village of Amherst, and I decided to get a bunch of glass mason jars, and I took them around and collected samples from all of my neighbors,” said Tarion O’Carroll, a Nelsonville resident. “About half of those samples came back above ten, so that’s kind of where I realized, you know, this village had had an issue.”

O’Carroll’s water was also contaminated with nitrate, which prompted him to find another source of clean drinking water. He ended up finding an artesian well in another community to the east, and regularly drives there to haul water back home.

“In the summer, it’s not too bad,” O’Carroll said of his 90-minute journey. “In the wintertime, it can suck. It gets all icy and they’re heavy, so it’s not something I look forward to.”

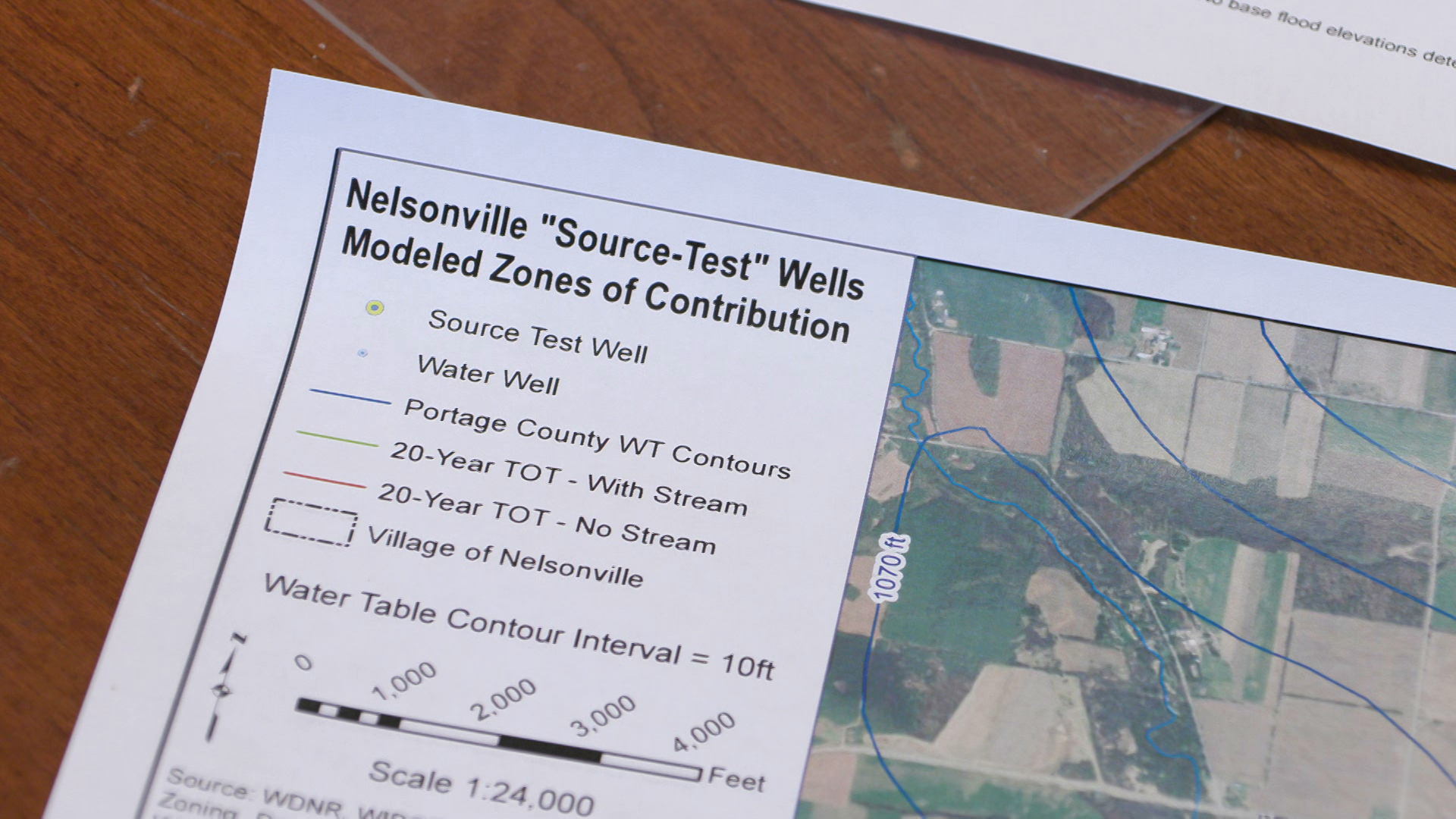

Meanwhile, over the next four years a small army of environmental scientists descended on Nelsonville, testing groundwater quality, how this water flows underground and what could be causing the nitrate contamination, among other questions.

“We wanted to try and answer the questions: Is there an issue? How big is that issue? What do we need to do moving forward to try and address it?” said Jennifer McNelly, the water resource specialist with Portage County whose work includes groundwater management.

To answer the first question — is there an issue — McNelly tested water from private wells in Nelsonville. There are roughly 80 private wells in the village, and about 60 owners agreed to tests. Among those wells tested, 47% came back above the 10 parts per million limit for nitrate set by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

“Statewide, about 10% of private residential drinking water wells exceed the nitrate drinking water standard. In Portage County, we run closer to 24% on average,” McNelly said. “We were surprised by [Nelsonville’s wells], we weren’t expecting that result.”

That data confirmed that there is an issue, and that it was fairly serious. McNelly and other scientists then started to work on the question of where the nitrate was coming from.

Generally, nitrate contamination is caused by either agricultural fertilizers or leaking home septic systems. In 2019, water from 25 wells in Nelsonville that registered nitrate above the 10 parts per million limit were tested again for source indicators.

“Eight came back with some sort of personal care products. All of them came back as positive for the agricultural herbicide breakdown products,” McNelly said. “So that was really indicative to us that these agricultural land users surrounding the village were having a significant impact on the water quality.”

Hydrologists were then able to map out Nelsonville’s water recharge zone, which is the area where rainwaters can end up in the aquifer underneath the area. They found Nelsonville’s recharge zone is located primarily under agricultural land.

“Agriculture is the primary source of nitrate in the drinking water wells of village residents,” said Pete Arntsen, a hydrologist with the consulting group Sand County Environmental. “Septic systems were tossed out there as the [possible] source, but [they are] really not likely to be much of the problem.”

A CAFO neighbor

Gordondale Farms is located at the north end of Nelsonville and has been in operation since 1900. Owner Kyle Gordon and his family have lived in the community for generations, and reside in a house next to the farm’s 1918-built barn.

Gordondale Farms is a large farm of about 5,000 acres, and is registered as a concentrated animal feeding operation with about 2,000 cows raised primarily for milk production. This livestock produces over 15,500,000 gallons of liquid manure every year. Looking to put this agricultural byproduct to use, Gordon uses it as fertilizer and applied more than 13,000,000 gallons to his fields in 2021.

Gordondale Farms is a 5,000 acre concentrated animal feeding operation located on the north end of Nelsonville. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Gordon rejects assertions that his farm is the cause of nitrate contamination in Nelsonville’s well water, despite testing data showing the presence of other agricultural byproducts. Instead, Gordon said more testing needs to be conducted, and that village residents need to make sure their septic systems are up to code before blaming the pollution on his farm.

“Our take on the nitrates from our standpoint is [that] our farm has had a nutrient management plan since 1981, and we followed every regulation that’s been put forth to us,” Gordon said.

Nutrient management plans are required for any crop or livestock producers that apply manure or other nutrients to agricultural fields, according to state law. These plans are intended to limit nutrient discharge into ground or surface water.

By all accounts, Gordondale Farms has followed every nitrate regulation required by the DNR. Gordondale’s CAFO permit was updated in April 2022 to include a plan to address nitrates in groundwater.

Gordondale Farms is home to about 2,000 cows that produce 15 million gallons of manure per year. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Gordon said he has even taken further steps in recent years. In most plots near the village, Gordon has planted alfalfa or Italian ryegrass, which soak up more nitrate in soil than corn. Those crops also require less initial nitrate for a full yield, he explained. Additionally, Gordon has run an anaerobic digester that turns some excess waste into electricity.

“So to be honest, it’s quite a puzzle. Like, where’s it coming from? Like, what is the deal?” Gordon said about the nitrate contamination.

Portage County officials said the statewide regulations for nitrate management aren’t working in the Central Sands region.

“Our agricultural community, by and large, is doing exactly what the state is telling them to do,” McNelly said. “We’re just starting to realize that in certain parts of the state, this uniform application or this uniform prescription isn’t working.”

The DNR proposed changes to nutrient management plans in late 2019 that would have set a more stringent nitrate limit for targeted areas, which includes most of Portage County. However, because the rules took more than 30 months to be developed, those rules were not adopted.

A midwife’s concerns

Once residents in Nelsonville learned their water was contaminated with nitrates, many started to scrutinize their past health concerns.

Jane Peterson is a licensed midwife who practiced in the area around Nelsonville for over 40 years. Around 2015, Peterson said she started to notice a significant uptick in the number of miscarriages among women in the area, around the same time more younger families had started to move to the village.

“[Someone] called me and said her sister lives in Nelsonville, and she’s had three miscarriages in the last 18 months,” Peterson said. “When one notices that there have been [numerous] miscarriages in a child bearing population the size of Nelsonville, it was clearly a red flag to me.”

Peterson admits these anecdotes do not constitute scientific evidence that can inform more solid medical conclusions.

“It’s important for that data to get collected and reported so that we can see [what is going on],” she said. “There are lots of things that are in our environment now that can come into play.”

Nelsonville resident Tarion O’Carroll fills 7-gallon jugs with water on a weekly basis from an artesian well located about 25 miles from his home so his family doesn’t have to drink their well water that’s contaminated with nitrates. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Once Peterson noticed these miscarriages, she told expecting mothers to drink only bottled water.

“It just felt like the right thing to do, to say, let’s reduce this risk factor,” she said. “We know that this is now a problem in the wells in Nelsonville, so just don’t drink that water.”

Monitoring wells

Despite testing results showing where the nitrate is coming from, Nelsonville has been in a deadlock on what to do about the contamination.

One proposal includes the construction of three monitoring wells in the village, so residents can figure out if there’s clean water deeper underground. Similarly, the DNR has required Gordondale Farms to implement three monitoring wells near its farm plots. Those wells would test the immediate impact changed farming practices have, instead of waiting years for nitrates to reach wells in the village.

However, the future of both sets of proposed monitoring wells is in doubt. Funding for the monitoring wells in Nelsonville initially passed a county board vote by a margin of 13-11, but was subsequently vetoed by Portage County Executive John Pavelski.

“Capital improvement projects are designed to fund projects that benefit the county as a whole, for all citizens that are affected and/or have access to what those funds are used for,” Pavelski said in a press release. “If we open up this Pandora’s box of county funds, we could have other municipalities, areas, or groups of the county requesting funds for their projects as well.”

Sand County Environmental hydrologist Pete Arnsten worked through a variety of tests to map out Nelsonville’s groundwater recharge zone, and found it’s located in mostly agricultural land. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

As for the DNR-mandated wells on Gordondale property, Gordon himself would be responsible for their full cost. However, Gordon is fighting that order in court.

“If you’re going to solve the nitrate problem and I handed you $200,000, the last thing I would do is put in monitoring wells that’s just going to accuse somebody,” Gordon said. “How do I feel about having monitoring wells accuse us? Well, how would you think I would feel?”

While county funding for the village monitoring wells has been halted, Nelsonville resident Lisa Anderson said she still hopes federal funding will allow its completion.

“We want the [Portage County] Land and Water Conservation Committee to do what it is mandated to do under state statute, and that is to protect the resources of the county,” Anderson said.

The DNR’s role

While updated nitrate limits were not adopted, the DNR said it is still looking at options to reduce nitrate contamination.

Jim Zellmer, deputy administrator in the DNR’s Environmental Management Division, said the agency has started conversations with Portage County to figure out what practices might be able to reduce the amount of nitrate being added to the soil.

“We continued the discussions working with our stakeholders on making progress, really for that shared goal of reducing nitrate contamination to the groundwater,” Zellmer said in a Dec. 9, 2022 interview on PBS Wisconsin’s Here & Now.

While the DNR examines ways to reduce the amount of nitrate in groundwater, $10 million in federal American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds have been allocated to drill new wells or install treatment filters for Wisconsinites with contaminated well water.

“So far, there is enough money there to fund in excess of 1600 well replacements,” Zellmer said. “We’ve only had 40 applicants.”

However, this program only covers a maximum of 75% of the costs to install a new well, which means residents will still have to pay out of pocket to ensure access to a cleaner water source. Anderson also said people in Nelsonville have been waiting weeks for contractors to estimate the cost of new wells, a number required to apply for ARPA funds.

“There were five people that I was aware of that tried to apply but are on hold because of the unresponsiveness of drillers,” she said.

Decisions on if new, deeper wells are needed will have to be made soon, since any solution for nitrate contamination will take at least 5-10 years to see any effect due to how slowly nitrate contamination spreads in groundwater.

The spreading of cow manure to add nutrients to soil to increase crop yields is a common source of nitrate contamination in groundwater. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Despite the relatively slow pace of any potential fixes, Nelsonville residents say they still have hope for the future.

Gordon is urging continued testing, even as he has drawn ire from residents who say he isn’t doing enough to cut excess nitrate.

“We’re missing [data] every year that goes by — we miss opportunities to record, to learn, to fix this problem,” he said. “We’re just wasting time by pointing fingers.”

More testing is an approach that Anderson is in support of, as well.

“Having these monitoring systems [would be] a step in the right direction,” she said. “The county monitoring system will give us an idea of what our future looks like, and help us make decisions about if a person has to drill a deeper well.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us