Major promise, big questions flow from a PFAS cleanup study in Madison

A Canadian company has launched a bioremediation effort around the Dane County airport and National Guard air base that deploys soil microbes to consume the vexing chemicals — within weeks, early results showed positive outcomes, but the science behind this work remains unclear.

By Will Cushman

January 13, 2022 • South Central Region

An airplane takes off near the site where Starkweather Creek exits Truax Field Air National Guard Base and flows through pipes that feed the water downstream toward Lake Monona in Madison. In 2019, the creek contained higher levels of PFOA and PFOS — two more scrutinized types of hazardous PFAS — than any other waters the Department of Natural Resources tested that year. Photo taken on Aug. 5, 2021. (Credit: Isaac Wasserman / Wisconsin Watch)

Soil and water polluted with PFAS present a daunting challenge. A class of more than 5,000 chemicals, PFAS include compounds that can stay in the environment indefinitely and have been very difficult to clean up, giving rise to their “forever chemicals” moniker.

This stubborn persistence is one reason state and local officials responsible for addressing one major site of PFAS contamination in Wisconsin say they’re excited about early results of a pilot study that uses a new approach aimed at removing the chemicals. Its method harnesses microbes that consume PFAS, and while it appears to hold potential promise, much about it remains unknown. Among these unknowns is how, exactly, the process works.

The project is a brainchild of Tim Repas, president of a Canadian company that specializes in cleaning polluted sites via biological processes, which is known as bioremediation. The company, Fixed Earth Innovations, is partnering with Verona-based ORIN Technologies to complete the pilot study on behalf of the Dane County Regional Airport and the Wisconsin Air National Guard.

ORIN specializes in bioremediation techniques, and the Wisconsin company managed the installation of the system being assessed in the pilot study. ORIN was also behind a different experimental treatment of PFAS-laden water leaving the site that the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources deemed ineffective.

The Air Guard, Dane County and city of Madison are jointly responsible for remediating PFAS contamination around the airport-adjacent base at Truax Field. PFAS have been linked to a variety of health issues including thyroid dysfunction and liver disease, meaning contamination sites pose a long-term threat to the health of the people who live and work around them. PFAS contamination in soil and groundwater is a costly problem facing a growing number of communities around Wisconsin, including Marinette, La Crosse and Eau Claire.

The year-long project kicked off in late December 2021. Microbes collected from soils near the airfield in Madison began devouring PFAS compounds that contaminate a 1,600-square-foot area near a fire station located across the main runway from the commercial airport.

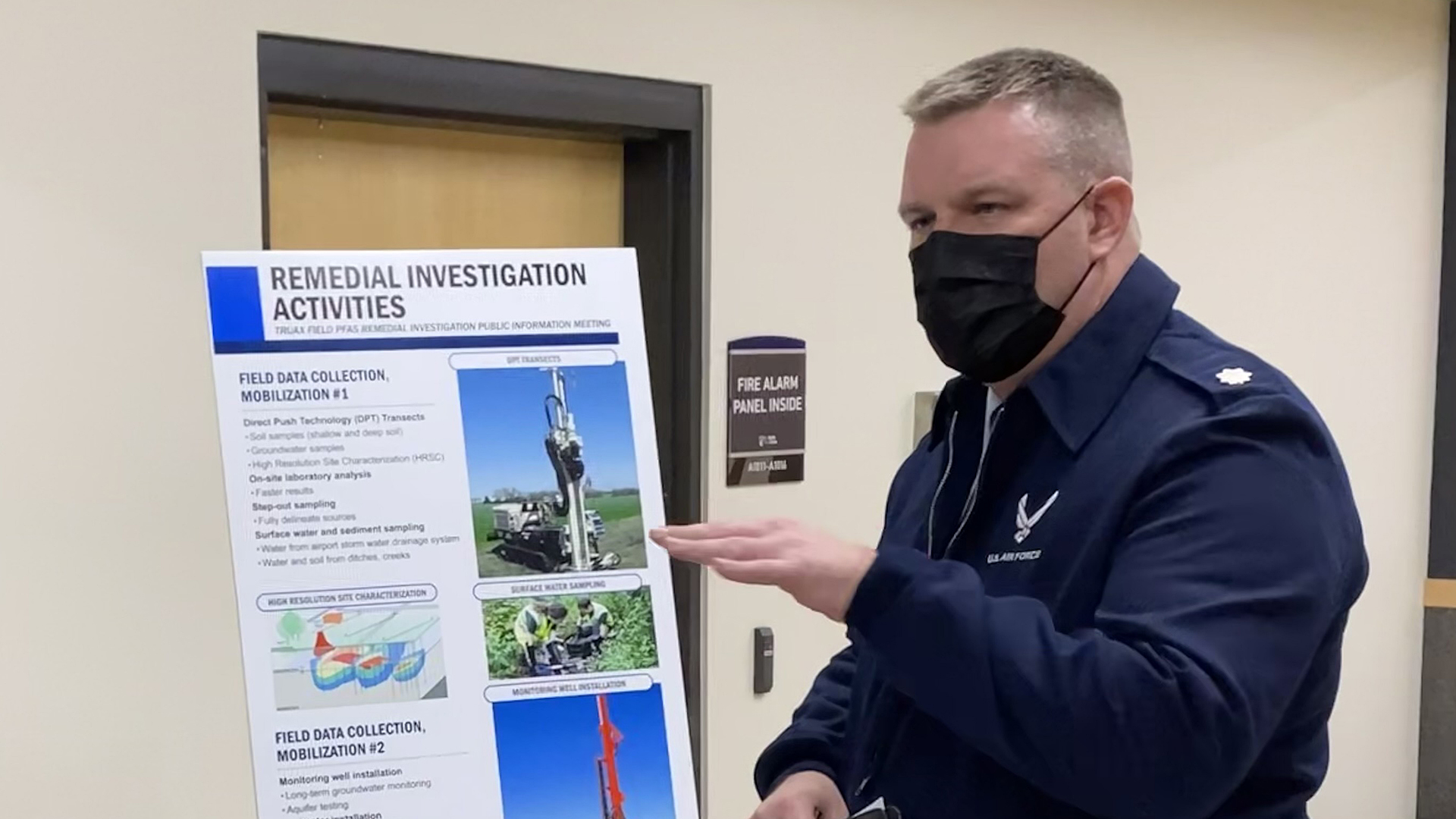

Only three weeks later, Lt. Col. Dan Statz of the Wisconsin Air National Guard described its early results as “very promising” during a Jan. 11 open house that presented an overview of a much larger and longer-term cleanup effort at both the airport and military base.

Statz said the microbial activity had reduced the observed presence of some PFAS compounds within the pilot site by 50-90% within those handful of weeks.

Lt. Col. Dan Statz of the Wisconsin Air National Guard describes the long-term PFAS remediation plan for the Dane County Regional Airport and Truax Field in Madison during an open house on Jan. 11, 2022. (Credit: Will Cushman / PBS Wisconsin)

But questions about the process remain unanswered, including its potential costs. A spokesperson for the Air National Guard declined to provide a figure for how much the pilot study cost, but said it was jointly funded by the Dane County Regional Airport and the Wisconsin Department of Military Affairs.

Perhaps the most significant lingering question, though, is how the microbes actually break down the chemicals and whether this process creates any unexpected issues.

Microbes that feed on PFAS

The Canadian company that developed the cleanup method being piloted in Madison, got its start in bioremediation after identifying microbes that feast on hydrocarbons that pollutie oil and gas sites in British Columbia.

“All of a sudden we were cleaning up sites in 15 days that otherwise would have taken five years before,” said Tim Repas, the president of Fixed Earth. “So, then it’s like, ‘Well, why not other pollutants?'”

In search of a “good challenge,” the company turned its attention to finding microbes that might consume PFAS, an area of research that’s growing but remains in its infancy.

“There were literally no papers to base what we were doing on, so we were kind of in no-man’s land,” said Repas.

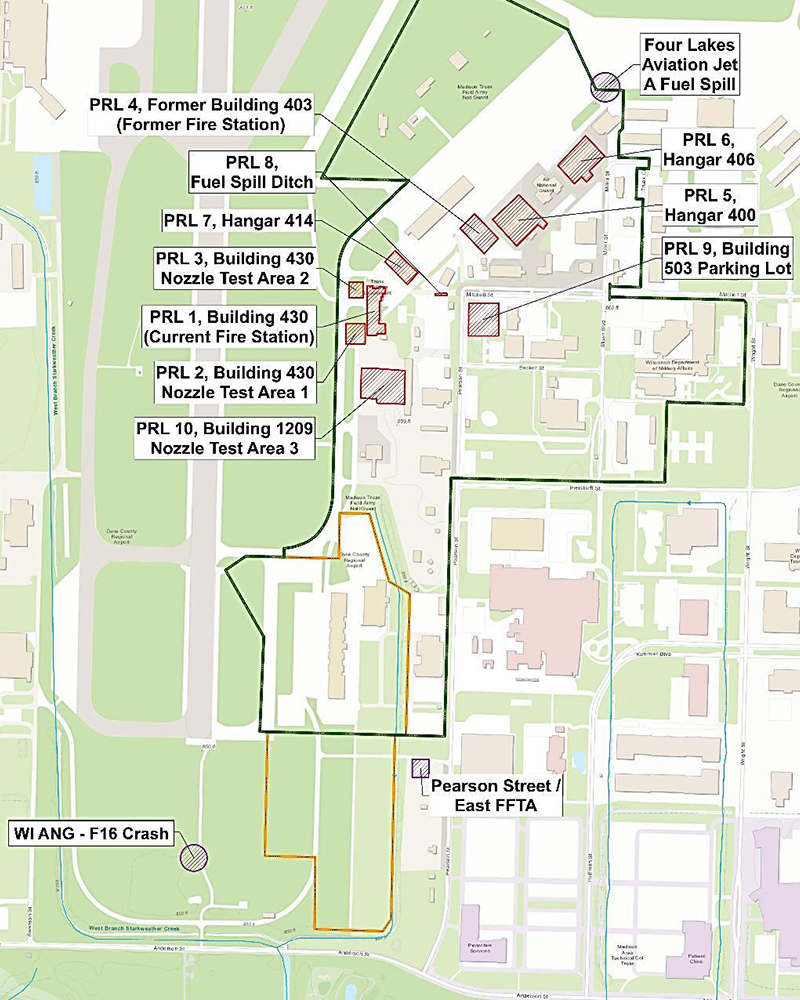

A map shows the sites of PFAS “potential release locations” (PRLs) at Truax Field in Madison. The site of a bioremediation pilot study is labeled as PRL 2, which sits near a fire station used by the Wisconsin Air National Guard where PFAS containing firefighting foams have been tested. (Credit: Wisconsin Air National Guard)

Sooner than expected, Repas found promising candidates living in soils from multiple sites in North America. A series of lab experiments in 2019 and 2020 provided evidence that these microbes were indeed breaking down PFAS. A small field study in Michigan provided similarly promising results, Repas added.

Citing trade secrets, Repas declined to identify the microbes driving the process, but said they aren’t confined to a single species or location. Instead, Fixed Earth has developed a method of identifying microbes already present at or near contamination sites that, under the right conditions, are able to digest and transform PFAS into different chemicals. That’s how the process has worked at the Madison airport.

Still, research into bioremediation of PFAS among the wider scientific community remains nascent, and Repas acknowledged the company has much to learn about the biological and chemical processes in play.

“The biochemistry of what actually happens,” said Repas, “is a really tricky question.” He said the company has a working theory of what might be happening at the molecular level but needs to conduct more studies. A major focus of its work to-date has been identifying byproducts of the bioremediation process.

“What we want to be really careful of is that we’re not forming something that’s just hiding [PFAS] and making it invisible to the tests, because that’s not really cleaning it up, or turning it into something that could be as or more dangerous,” Repas said.

So far, the process seems to be producing carbon dioxide and fluoride, he noted, adding that lab and field experiments have not indicated other, less desirable byproducts.

Excitement and skepticism

While Tim Repas and his colleagues are growing more confident in their bioremediation technique, they acknowledge its novelty and the speed at which the pilot study has progressed might give pause to some observers.

Among those potential skeptics is Martin Shafer, a scientist at the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene whose work includes analyzing how chemical contaminants like PFAS interact with their environments. Shafer welcomes more research into how to remediate PFAS contamination, but believes a lot more lab work needs to be done first.

“I think it’s really early to take some of these [lab] studies and put them into an environmental system, even if it’s very well constrained,” he said.

In particular, Shafer said there is not a good scientific understanding of the mechanisms that break the super-strong bond between carbon and fluorine atoms that make some PFAS compounds so long-lasting and difficult to destroy.

“Until we characterize how that mechanism of bond breakage is occurring, I think it’s just maybe premature to really move it to a field scale,” he said.

Workers install equipment for a PFAS bioremediation pilot study at Truax Field in Madison in November 2021. (Credit: ORIN Technologies)

Trina McMahon, an environmental engineer and microbiologist at UW-Madison, said she agreed that a field study looking into bioremediation of PFAS would need to be well controlled to ensure that any unexpected byproducts don’t have a chance to escape.

“I would expect that they have the site under pretty good control,” McMahon said. An expert in freshwater microbes, she has done some research on microbial bioremediation of chemicals, but not PFAS.

Describing Fixed Earth’s findings as “really exciting,” McMahon said they underscore the untapped potential of the Earth’s tiniest organisms.

“Every time I hear about something like this, I get even more excited about what I study just because microbes are so amazing,” McMahon said. “They have this tremendous capacity to chew on whatever we throw at them, and every time we come up with a new chemical that we think is never, ever, ever going to get broken down, they always find a way.”

Equipment sits in place as one of several 25-foot deep holes drilled over a 1,600-square-foot area is prepared for a PFAS bioremediation pilot study at Truax Field in Madison. (Credit: ORIN Technologies)

McMahon and Shafer both said they expect scientific understanding of PFAS and the potential for bioremediation of these chemicals to grow rapidly in the 2020s as research interest in their cleanup explodes.

“I would predict that in the next year we’re going to see a lot more reports of this kind of thing, and get a better handle on what kinds of organisms can do it,” McMahon said.

Meanwhile, the pilot study in Madison is scheduled to wrap up in December 2022, followed by a thorough evaluation, according to Repas. The study was approved by the Wisconsin DNR, which is among the many entities grappling with PFAS that will be closely monitoring its results.

Sarah Hoye, a spokesperson for the DNR, said the pilot meets regulatory requirements and does not pose any concerns for the agency’s scientists. Still, she noted that Fixed Earth’s methods have not undergone scientific peer review, and said the DNR’s regulatory approval did not constitute an endorsement of the company or its methods. She indicated that DNR scientists would be eager for data to be rigorously reviewed following the pilot.

“If PFAS concentrations are lower at the end of the pilot study than at the start, the question is whether this process has biodegraded the PFAS compounds or whether there are other processes … taking place,” Hoye wrote in an email to PBS Wisconsin.

Repas said Fixed Earth intends to share data from the pilot study with the DNR. Whether or not this potential bioremediation approach proves successful, there will be several more pilot projects, possibly at larger scales, before the method becomes commercialized, he said.

“We can make lots of things happen in the lab, but making sure they happen in the real world is obviously really the critical thing,” he said.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us