Climate change is warming Wisconsin winters faster than other seasons

A wetter atmosphere and slower freezing of the Great Lakes has made wintertime temperature increases in Milwaukee and Green Bay among the highest in the nation as research projects that rises will continue.

January 11, 2023

Sun reflects off the frozen surface of Lake Michigan by the entrance to the harbor at Kewaunee in February 2015. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Milwaukee and Green Bay have experienced two of the five fastest warming winters in major cities across America over the past half-century, with their average temperatures warming by about 6 degrees Fahrenheit.

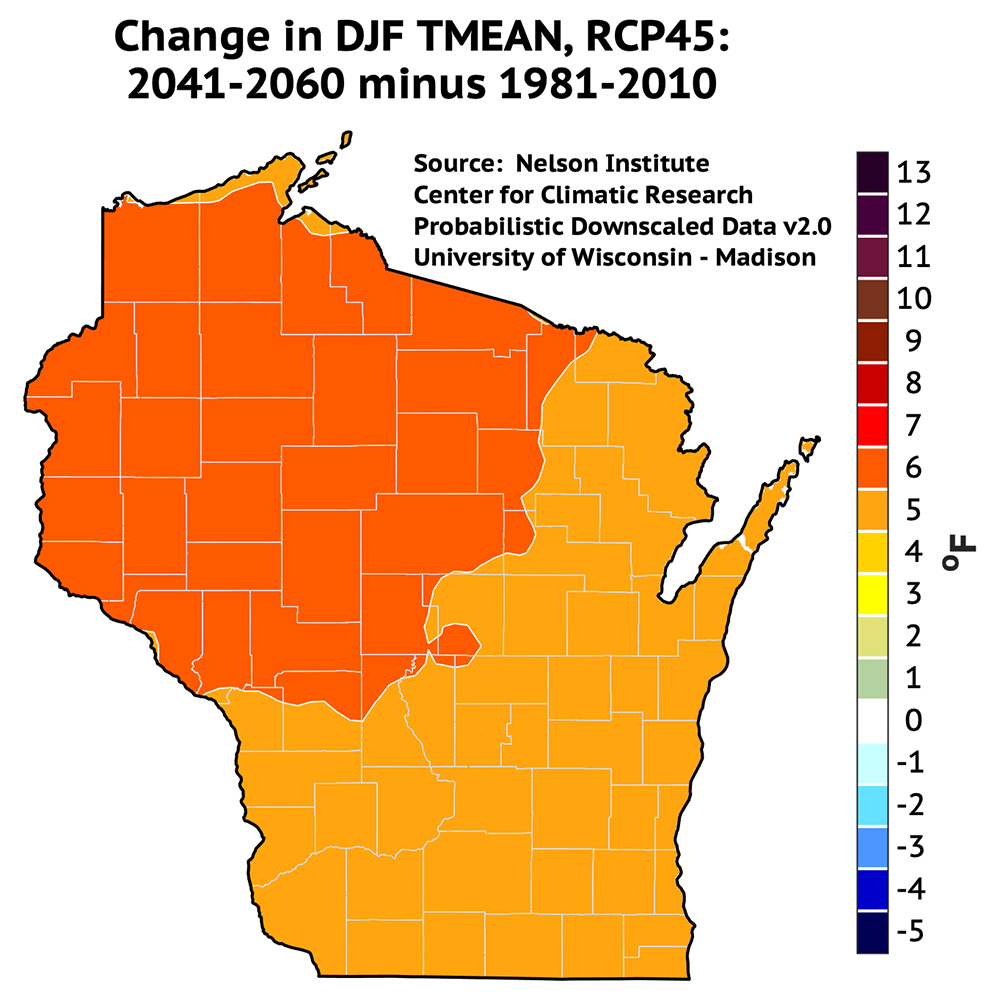

As impacts of climate change around Wisconsin are increasingly observed, winter has been found to be the fastest warming season in the state. A number of factors contribute to this seasonal pattern, including declining ice coverage on the Great Lakes, where Milwaukee and Green Bay are located. Projections from the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison show Wisconsin winter temperatures warming between 5-6 degrees Fahrenheit by 2060 compared to 1980.

As the planet’s atmosphere warms, more moisture is being trapped in the air than in previous decades. That greater humidity provides a buffer to cold fronts, making it harder for deep freeze temperatures to break through.

“When the air is really, really cold, there’s very little moisture in the air,” said Steve Vavrus, director of the Wisconsin State Climatology Office and an atmospheric scientist at the Nelson Institute. “So even a small increase in warming can cause a disproportionate increase in water vapor, which traps heat.”

Declining ice coverage on the Great Lakes and warming temperatures across the state are having an increasing impact on ecosystems that rely on frozen lakes and snowfall.

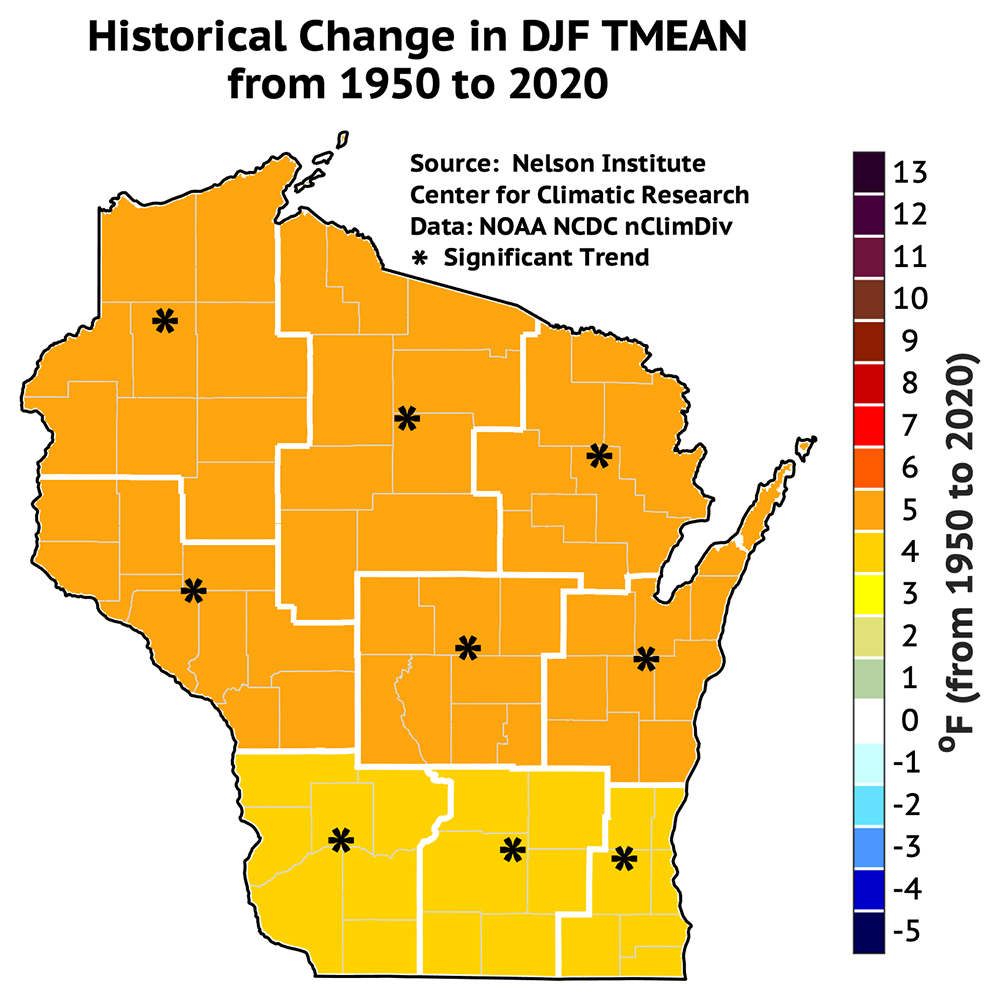

A map released by the Nelson Institute for Environmental Research shows changes in average winter temperatures in Wisconsin from 1950 to 2020, indicating warming that has already been observed in the state. (Credit: Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies)

“Over a small lake like Mendota [in Madison], there’s not too much of a warming effect from a late freeze up,” Vavrus said. “But if you’re up by Lake Superior or if you’re out along the shoreline of Lake Michigan, that’s a different story.”

When the surface waters of the Great Lakes do freeze, there’s virtually no limit to how cold the ice can get, which in turn cools air temperatures, Vavrus explained. However with more moisture in the air, extra heat can considerably slow ice cover, which in turn warms cities near the coast.

“The lakes have a buffering effect, so during the fall, coastal communities cool down more slowly, but that changes once you get an ice pack,” Vavrus said. “[Ice pack] allows the temperatures to really drop.”

Later freezes can also cause havoc for local ecosystems that depend on reliable timing for lake turnover. When a lake freezes over, its supply of oxygen is mostly cut off, which changes the density of water underneath ice.

As cooler water underneath the ice slowly sinks to the bottom of a lake, warmer water from the bottom wells up. This turnover process allows for oxygen to be replenished and nutrients to be distributed throughout the lake.

“A change in climate means we change the timing of [lake turnover] — in some places farther south, they don’t even get that turnover anymore because they don’t get cold enough,” Vavrus said. “We’re not looking at that anytime soon in Wisconsin, but that process regulates the entire ecology of the lakes, and can be thrown off by a warming atmosphere.”

A lack of ice cover can also cause more erosion around coasts. Winter storms can whip up big waves deep in the Great Lakes, but with ice cover near the shores those waves don’t usually make it to the coast. However, without the buffering effect of ice, these waves can crash directly into shorelines.

“In a warming climate with more open water and less ice cover, it means that when conditions are right, the waves would be huge off of Lake Michigan,” Vavrus said. “And if there’s no buffering effect of the ice cover, those waves can cause erosion, damage to the soil and to nearby homes.”

Inland areas experiencing winter warming too

While Milwaukee and Green Bay are warming faster than nearly all other major American cities, research by the Nelson Institute shows northwest Wisconsin is seeing the major regional effects of winter climate change.

Winter average temperatures in large swaths of northern and northwestern Wisconsin have warmed about a degree more than the rest of the state, and are likely to warm by about 6° Fahrenheit by 2060 compared to 1980. Meanwhile, southern and eastern parts of Wisconsin are expected to warm by 5 degrees Fahrenheit by 2060.

A map released by the Nelson Institute for Environmental Research shows projected changes in average winter temperatures in Wisconsin by the two decades between 2041 and 2060. (Credit: Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies)

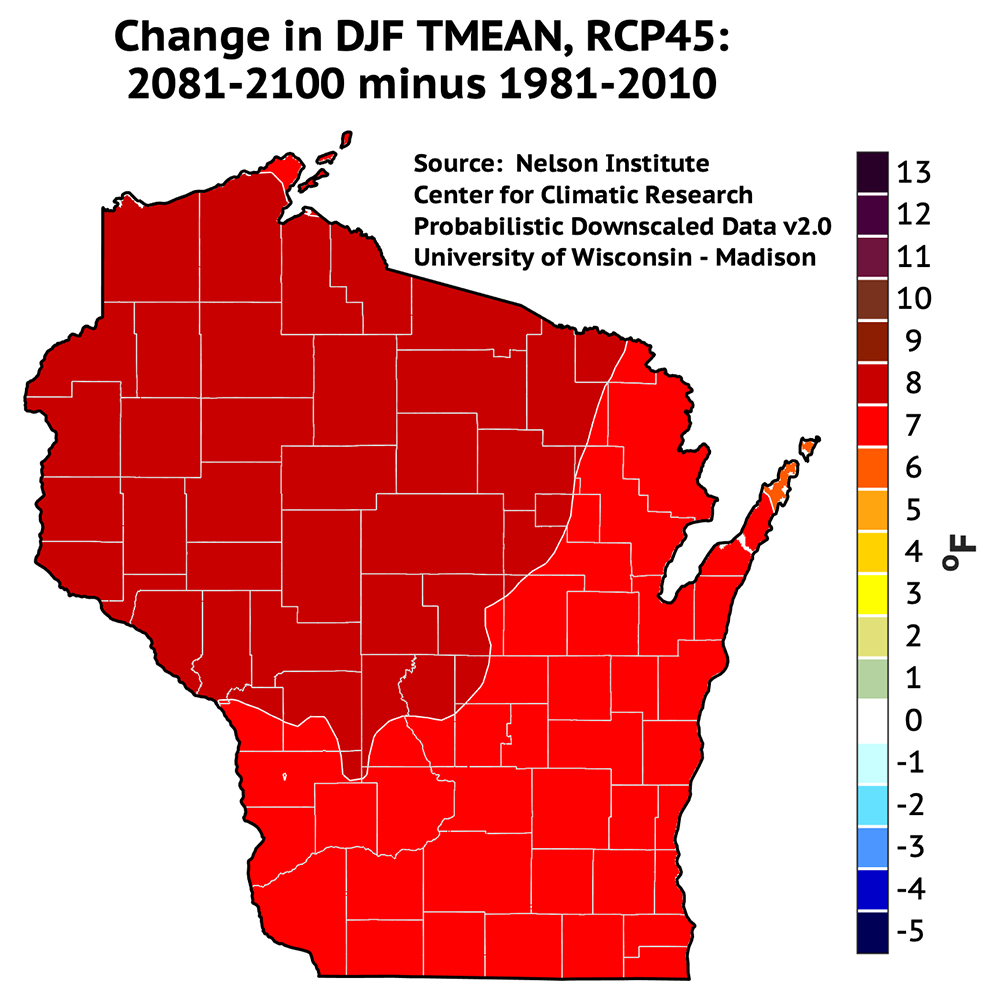

A map released by the Nelson Institute for Environmental Research shows projected changes in average winter temperatures in Wisconsin by the two decades between 2081 and 2100. (Credit: Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies)

“I suspected [the reason for warming] was reduced snow cover, but when I looked at places like Eau Claire, Rhinelander and Wausau, I didn’t see any downward trend in their snowpack,” Vavrus said. “I think that does beg the question what’s going on?”

A different pattern is seen in summer, on the other hand, as climate change has impacted southern areas of Wisconsin more than northern areas during that season.

While more research is needed to figure out why northwestern Wisconsin winters have warmed faster, Vavrus said in the long-term warmer temperatures mean less snowpack, which will further increase the rate of warming.

That warming is likely to have an impact on the logging industry in Wisconsin, as wetlands take longer to freeze, preventing heavy equipment from being able to traverse frozen ground in forests. Ecologically, the warming is likely to impact wildlife, with a classic example of the snowshoe hare, which relies on snow for camouflage during the winter months.

“The last two decades have been the warmest on record in Wisconsin, and the last decade was the wettest by far,” Vavrus said. “Those are trends that we expect to continue.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us