Wisconsin climate change research confirms impacts of warming winter nights

The UW-Madison Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies and the Department of Natural Resources have issued a scientific report examining how global warming has affected the state over the past decade, with measurable effects differing by season and time of day.

By Will Cushman

March 1, 2022

(Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

The first scientific report of its type in a decade highlights the changing climate is altering weather patterns, wildlife habitats, industry conditions and a myriad of cultural traditions across Wisconsin.

Among the most pronounced shifts observed by scientists is a rapid warming of low temperatures during winter nights. While warmer lows may rescue some fingers and toes on long winter nights, they also threaten Wisconsin wildlife and challenge industries that rely on cold conditions.

Warming winter nights are one of many changes scientists grappled with in the 2021 Assessment Report published by the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts, a partnership of scientists from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Gov. Tony Evers ordered the report in 2019 to follow up on the first such report published a decade earlier. The 100-page assessment documents the many ways the changing climate is manifesting in Wisconsin.

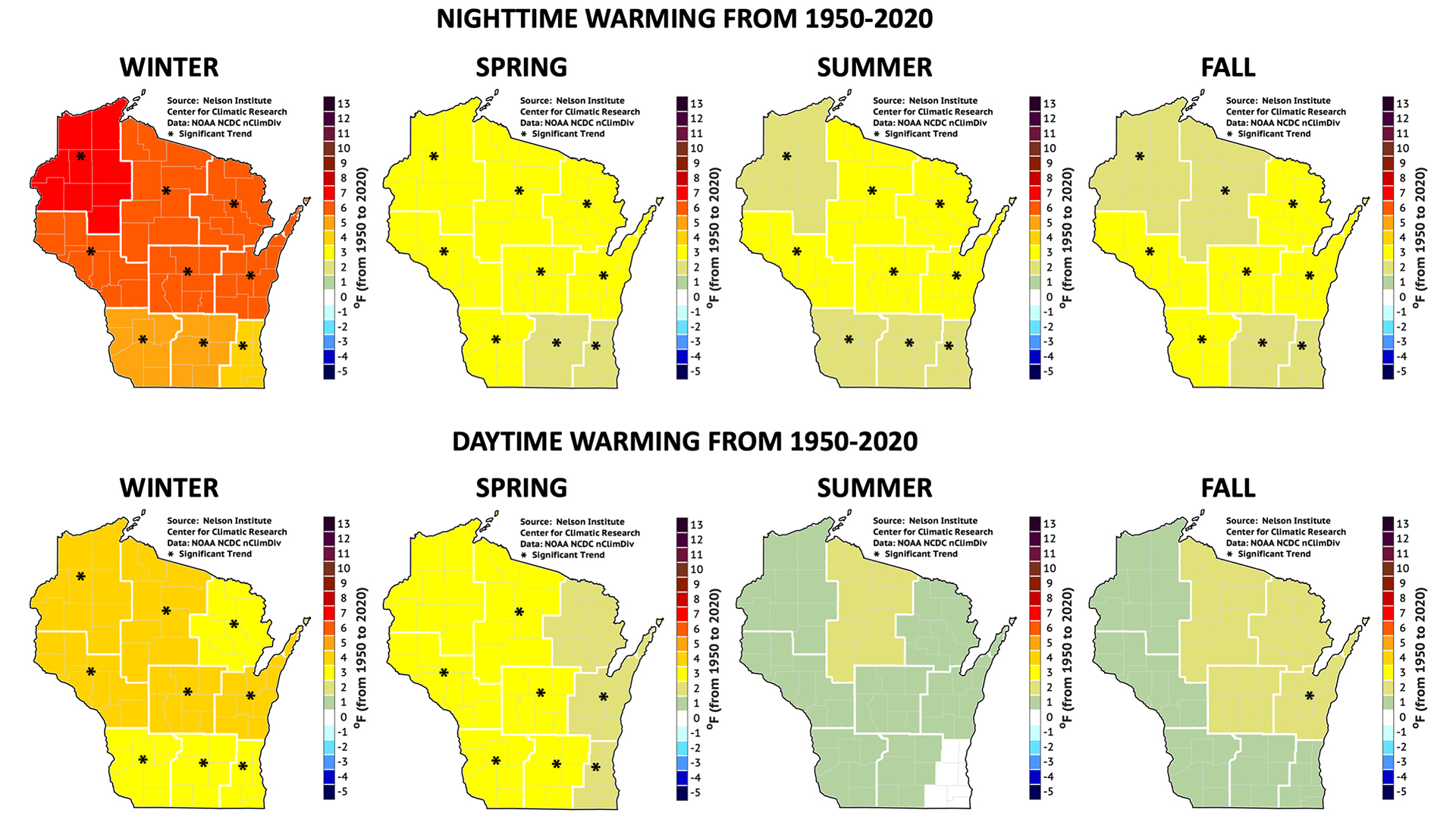

In terms of average temperatures, nighttime lows and winters as a whole have warmed more rapidly than daytime highs and summers, according to the report. Between 1950 and 2020, Wisconsin’s nighttime lows warmed between 4 and 7 degrees Fahrenheit, compared to warming of 1 degree Fahrenheit for summer daytime highs. This winter warming has been most pronounced in northwestern Wisconsin, the state’s coldest region.

Wisconsin’s warming trend is not evenly distributed between nighttime low temperatures (top) and daytime high temperatures (bottom), and from season to season, with winter nighttime lows warming fastest. (Credit: Courtesy of Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts)

This phenomenon, in which a warming climate disproportionately heats up the state’s coldest periods, fits scientific expectations. That’s according to Dan Vimont, a climatologist at UW-Madison who led the report’s climate science work. The Wisconsin data adds to evidence that’s been piling up globally for decades.

The phenomenon is partly due to increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide, which acts as an increasingly potent blanket keeping more solar energy trapped near the Earth’s surface at night. Another reason nights are warming faster is simply because the portion of the atmosphere affected by surface conditions — called the boundary layer — is thinner at night than during the day and therefore requires less energy to heat up.

Vimont said the phenomenon of more intense winter and nighttime warming has emerged as a robust indicator of climate change that the Wisconsin data confirms and strengthens.

“The more evidence like this we see, the more we’re inclined to be able to say things like, ‘Yeah, this is definitely climate change,'” he said.

The report details many ongoing effects of climate change on Wisconsin communities from the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River, including increased levels of extreme rainfall and flooding, as well as worsening water quality. A number of aspects of Wisconsin’s economy, ecosystems and culture are already feeling the effects of warming winters and winter nights.

These effects are impacting the state’s large forestry industry, which depends in part on cold winter temperatures to freeze the ground enough for heavy machinery to access remote off-road locations. Warmer winters also reduce snowpack, which insulates trees, and allow more opportunities for invasive and pest species to wreak havoc on the state’s forests.

Snow plays an important role in Wisconsin’s forest ecosystems. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Reduced snowpack also poses a threat to snowshoe hares, which the report identified as “critical species for forested ecosystems” in Wisconsin. That’s because the coats of snowshoe hares turn white in response to shorter days in the wintertime, a response meant to help camouflage the hares against a snowy landscape. Snowshoe hares are “increasingly mismatched with Wisconsin winters that have less and less snow cover,” according to the report.

Additionally, the report notes that declining snow cover and increasingly common winter “thaws” can threaten crops like alfalfa when they’re followed by a sudden and extreme drop in temperature, such as one experienced during a polar vortex early 2019. Alfalfa is an important forage crop supporting the state’s dairy industry.

Meanwhile, warmer average winter temperatures could reduce soil quality on agricultural lands, in part by allowing microorganisms more time to break down nutrient-rich organic matter in the soil during those months.

Then there are the impacts on winter tourism in Wisconsin, much of which depends on a consistent snowpack and consistently frozen inland lakes. For instance, a 2020 study from researchers at York University in Ontario documented how warming winters in regions that historically experience long periods of ice-cover have made frozen conditions less predictable, finding that accidental drownings during winter have increased in these places.

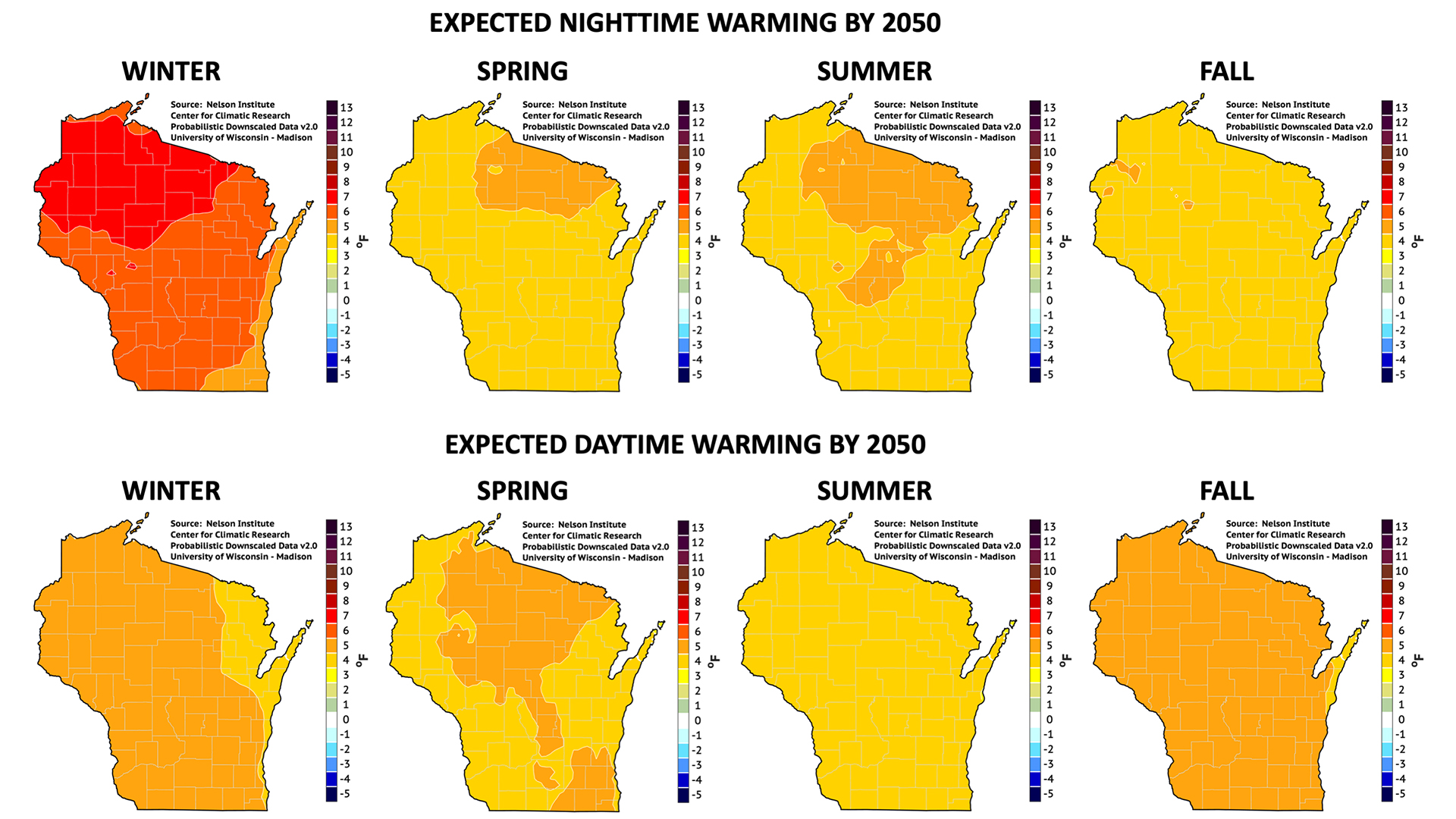

Wisconsin will continue to warm in all seasons through the coming century. Projections show that winter nights will warm the most, and summer days the least. These maps show the expected warming by mid-century compared to conditions at the end of the 20th century. (Credit: Courtesy of Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts)

Vimont pointed to even more potential impacts on the horizon, as the report forecasts that winter nights will continue to warm most quickly in Wisconsin through 2050. This warming will likely see more northern migration of insect species that can cause illness, he said.

“The mosquito that carries Zika [virus] by mid-century is likely to be able to overwinter occasionally here in Wisconsin,” said Vimont. “That’s not a fun one to think about.”

While the present and future impacts may not be pleasant to consider, Vimont said he hopes the report provides a catalyst for more individual and group action around Wisconsin to mitigate and adapt to a changing climate. Such actions would include further movement from relying on fossil fuels to increased use of renewable energy generated in-state, such as wind and solar, and shifting away from car-centered routines and development.

“What strikes me about the process in this report is that a big difference from 10 years ago is all the stories of people who are experiencing climate change now and all the stories of those people who are already taking action,” he said. “This isn’t something that’s a hypothetical anymore. We understand it, we’re being affected by it and we’re taking action.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us