Redeveloping Madison's Bayview community with design justice

A long-time center of cultural diversity in Wisconsin's capital city, the Triangle neighborhood is home to a low-income housing development that seeks out the perspectives of people who live there.

By Murv Seymour | Here & Now

September 22, 2022 • South Central Region

On the edge of Madison’s south side sits a tiny community that represents a slice of Wisconsin’s diversity.

“All of the housing that’s on the triangle, including Bayview, is low-income housing,” said Mary Berryman Agard, a board member of the Bayview Foundation.

“Bayview is 50 years old,” said Alexis London, the foundation’s executive director.

“It has been for 50 years a center of really quiet promise,” noted Berryman Agard. “This is an area of the city that used to be originally Ho-Chunk land, and then it became later on land that was settled by waves of immigrants coming into Madison — Albanians, Italians, Jewish people, African Americans.

“Bayview has always been culturally diverse,” observed Xong Vang. “Language might be a barrier, but it doesn’t stop the residents engaging and talking to one another and just having that sense of community.”

Long-time Bayview resident Xong Vang highlights the diversity of the community and shares his excitement for its infrastructure being redeveloped. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

“Bayview is a place I love,” said Nina Okwali Nanonah. “I’ve been here for over 18 years.”

Both of these longtime Bayview residents emphasize its close-knit community.

“Here it’s more than just townhomes side by side, more than just brick buildings side by side,” Vang said. “Everyone knows everybody — the parents, the kids, the grandchildren.”

“We look out for each others,” Okwali Nanonah said. “Your kids can go out and play without you getting worried of anything happening. It’s a place that’s really really free, safe and is centered on families.”

Nina Okwali Nanonah has lived at Bayview for nearly two decades, and describes it as a community centered on families. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

“We have a different way of providing housing,” said Berryman Agard.

That different way also provides “job services, social services, some health services, education, children’s programs and a significant commitment to arts and public art and placemaking,” noted Berryman Agard. “The importance of Bayview is it is one of the most successful affordable housing communities around.”

“You can wait for five, six years waiting to get one apartment that’s affordable,” Okwali Nanonah noted.

“Building affordable housing in urban environments close to the things that people need to get to is really essential,” said London.

Alexis London is executive director of the Bayview Foundation, which is pursuing the redevelopment of low-income housing and associated community services in the historic Triangle neighborhood located between Madison’s south side and the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus. She emphasizes the neighborhood’s access to workplaces, transportation and other essentials. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

“We’re located within a mile of downtown Madison. We are only blocks away from campus. We are blocks away from the Monona Bay. And so here you have access to transportation, jobs [and] really good schools,” she explained. “Banks, health care facilities, all of the things that all of us need.”

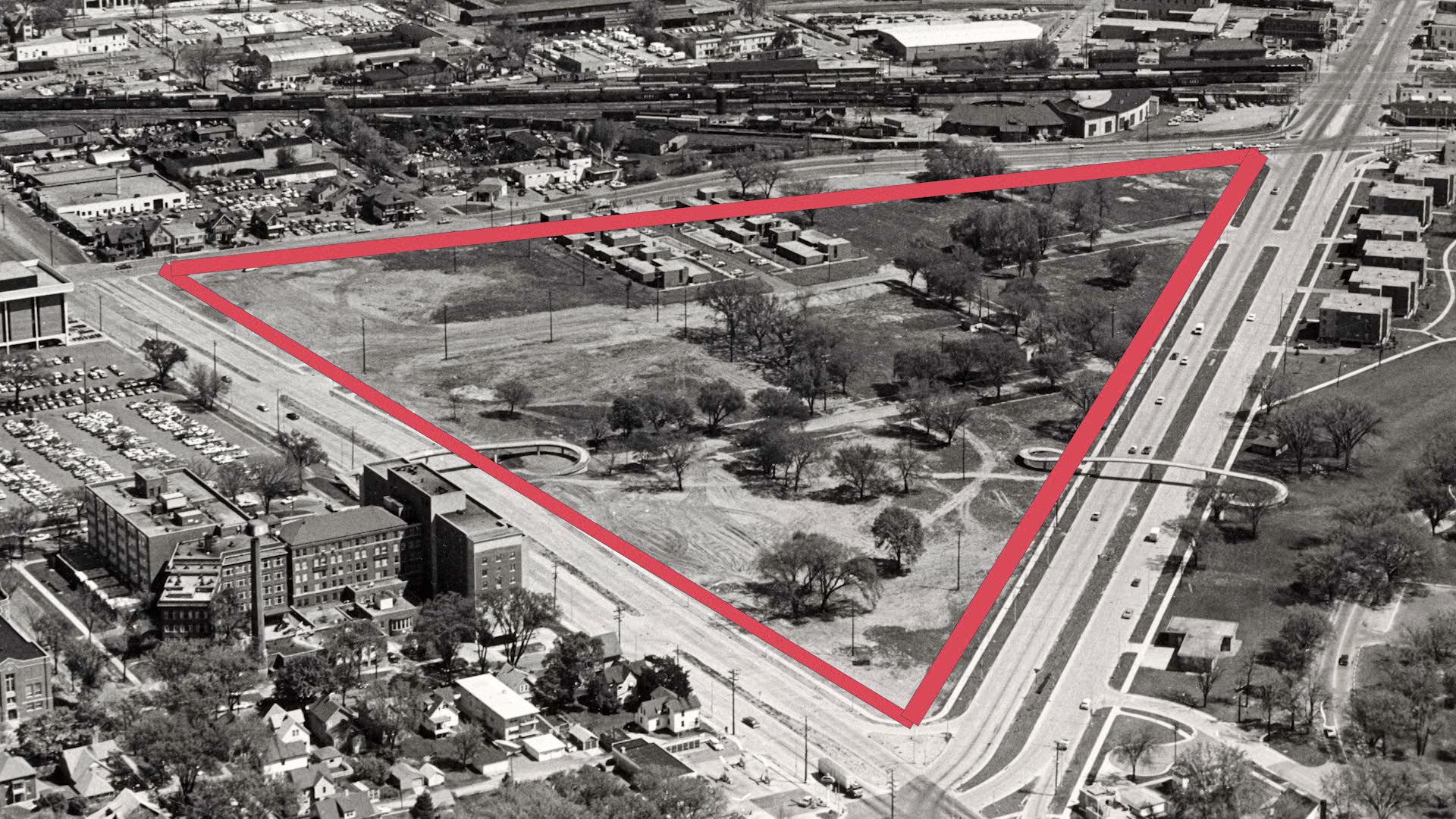

Also known as the Greenbush community, and nowadays the Triangle because of the unique shape of the block where it sits, the sense of diverse community there dates back more than 50 years when it first began to take shape. Back then when city leaders chose to rebuild the area, it would have a devastating impact on this mainly minority community.

“I think that the history on the Triangle is one that … is really complicated,” London said.

“In the ’60s, that sort of blossoming, fruitful, scruffy immigrant area was devastated by old-school urban renewal,” said Berryman Agard. “Federal money became available to cities all across the country to remove what was considered to be urban blight.”

Mary Berryman Agard is a board member of the Bayview Foundation, a non-profit organization in Madison that provides housing and services to low-income residents. She highlights the long-term resiliency of the Triangle neighborhood and the people who live there. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

She described how this history unfolded.

“Homes were bought out … You had to sell or you were going to be condemned out,” Berryman Agard explained. “The neighborhood was taken down without really considering what would happen to the residents who lived there.”

“People went out to secure housing and there was not more affordable housing to be had,” she continued. “They lived with relatives. They lived outdoors, sleeping in what’s now Brittingham Park. They left the community. They tripled up and rented apartments. They survived, but not well and not perhaps fairly.”

This loss inspired some people to speak out.

“A group of advocates who at that time said, ‘You can’t just take down all this housing where all these low-income people are living. Where are they going to go? You know, what are you doing, city of Madison?,'” said Berryman Agard.

In the 1960s, buildings around the Greenbush neighborhood in Madison — bordered by West Washington Avenue, Park Street and Regent Street — were razed in a process of what was called “urban renewal,” leaving many residents without housing and separated from their community. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

In 2021, ground was broken on a more than $60 million renewal effort that will fund new accessible apartments, new townhomes and an expanded arts and recreation center. Bayview will be able to house 500 people, 200 more than it currently houses.

Construction crews have worked on this project for a little more than a year. They’re almost ready for people to move in. But, unlike the past, this modern-day redevelopment is being done in a process called ‘design justice,’ which means the new, improved Bayview is built with the voices and visions of the people that live there — and not without them.

“I’ve lived here for many, many years,” said Vang, who took part in ceremonies that day. He couldn’t be happier about the transformation of the place he calls home.

“I’m very excited for this redevelopment,” Vang said. “These buildings are very, very old.”

Construction crews work on the top floor of a new apartment building that is part of the first stage of the Bayview redevelopment. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

“Across the state, people are just beginning to understand that when you redevelop affordable housing or housing of any kind, you redevelop it with the people who live there, not in spite of them, not without them,” said Berryman Agard. “For us, that meant holding 25 community meetings in three languages.”

She explained how the process worked.

“We would say to our residents, ‘What are your concerns about ‘X’?’ They would answer in the meeting, ‘one, two, three.’ And we would say to the architects, ‘Did you hear that they said, ‘one, two, three,? Could you please come up, with some solutions for ‘one two, three’ and come back to us?'”

“They have, like little booklets of colors to say, ‘Hey, what color do you like? Do you like this one? This one, this one? How do you want a roofline to be?’,” Vang recalled.

“They’re making it possible for us to have a voice,” Okwali Nanonah said.

An architectural rendering shows an aerial view of the planned Bayview redevelopment, which consists of two apartment buildings, townhouses and and expanded community center, among other design elements. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

“Instead of having basements, we’re making people’s living spaces larger. We’re creating more storage rooms that are either in individual apartment units or in common areas. We’re talking about shared library of tools or event supplies that people might be able to use and share in the future,” explained London.

“The arts are a big part of our history and our future,” she added.

London shared some of the specific plans in the works.

“We are planning to double the size of the community center. We’re planning to have additional community spaces that are classrooms that serve specific age groups. We’ll have a commercial kitchen. We’ll have a special dedicated space for seniors and adults, for career development, for business planning. We’ll have an early childhood space that will provide early learning experiences, as well as parents engagement classes,” she explained.

“Without this kind of a model of housing, people are going to end up completely stretched and taxed,” said London. “They’re going to be paying more than 50% of their income on rent, so they won’t have as much money to pay for clothing, books, food — all of those essential services.”

The Bayview community redevelopment is a multi-stage process, with subsequent stages slated to be completed in 2023 and 2024. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

“People need places to call her own and a roof over their head so they can concentrate on things, simple things like work, daycare, health,” said Vang.

“When you are comfortable in a place that is good, you’re going to be happy,” said Okwali Nanonah.

Without Bayview, both Vang and Okwali Nanonah are unsure where they would call home.

“Wow, I don’t really know where I’ll be living. As a foreigner, I probably be stranded, I probably be homeless,” Okwali Nanonah shared.

“That is a model of community development of housing development that the entire state would benefit from,” said London about the Bayview development. “And it could happen with all different types of communities. I think it’s especially important that it happens in low-income communities of color because those people are typically people who don’t have as much power who are left out of the conversation.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us