Pandemic Extends Wisconsin Scientist’s Stay in Antarctica

That’s the bad news. But, what if your home was in the safest spot in the world?

By Andy Moore | Here & Now

May 14, 2020

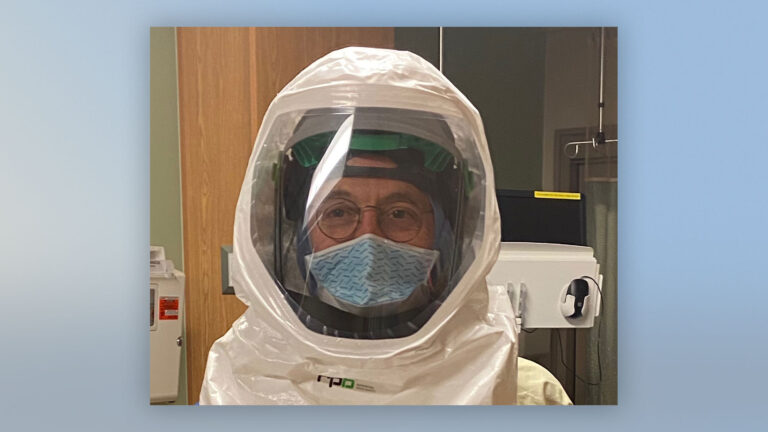

Palmer Station Scientist Carolyn Lipke

It was a balmy, 21-degree late summer morning Wednesday on Anvers Island in Antarctica, a place where the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans are just around the corner from each other, when Wisconsin scientist Carolyn Lipke picked up the phone. An Onalaska native with a Master’s Degree in bacteriology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Lipke had spent the morning tending to oceanographic and atmospheric instruments before helping co-workers get to the field and into boats for a day of data gathering.

“Oh!” she said. “It was also my turn to clean the bathrooms.”

Lipke and 19 other researchers have lived and worked at the Palmer Research Station since last October. Their term was scheduled to conclude in April. The pandemic is keeping her in place for another couple of months due to extra health precautions the National Science Foundation is taking with her teams’ replacements before sending them down from North America.

Palmer Station, Antarctica

Lipke said she’s anxious to come home to Madison. That makes the delay bad news. The good news? Palmer Station is 100 percent virus free. When it comes to COVID-19, Antarctica is known as the safest spot in the world. Located on Anvers Island off the Antarctica Peninsula, Palmer is the only United States research station north of the Antarctic Circle, a mere 9,600 miles from Lipke’s native La Crosse County.

Lipke’s bunk room

It’s safe to say Lipke knew about the rigor of isolation long before the rest of us. Living 24/7 in a community of 20 in one of the most desolate areas of the world brings special challenges. For most of the past eight months, she’s shared a tiny room and a bunk bed with another staff member. “It’s like going back to college,” she said. “We’re all used to it. We’ve all worked before with people living on top of each other and we learn to be very forgiving with each other. People here all work for a common goal.”

It’s ironic that a scientist became aware of the early transmission and worldwide threat of the Cornonavirus “late,” as she describes it. But that’s what happened given the day-in-and-day-out vacuum of research and isolation one experiences in a place like Antarctica, a place where 98 percent of the continent is covered by ice. “It (awareness of the oncoming virus) was a little slow. I sort of shut out social media and the news. I kind of shut that out down here. It took me a while. I don’t think any of us here fully comprehend it yet.”

Indeed, the rest of the world is, well, like another world when it comes to adjustments in lifestyle that await Lipke and her teammates upon re-entry to the Northern Hemisphere. “We don’t have to deal with social distancing. We don’t have to wear masks or watch what we’re touching,” she said. There is, however, one pandemic behavior that Lipke will have down pat when she returns. “I work in a lab,” she said. I’m used to washing my hands a million times a day.”

With much of the U.S. still living in a shutdown, does Lipke feel any guilt about living in the safest place on the planet? She said the answer is “yes,” for some, but not for her. “It’s not like I pushed anyone out of the way to be in this position. I feel fortunate.”

In fact, Lipke’s good fortune has prompted friends and family to ask her why she would even want to return to Wisconsin. She laughed at the thought of the question. “Why?” she said. “How about fresh vegetables, fresh fruit, sun? How about grass?”

Palmer Station Scientist Carolyn Lipke

Lipke’s eventual journey home is as much of an expression of her current isolation as anything else. It will take five days of travel on a ship to get to South America. A couple days of air travel will follow. She said when the day finally comes to leave, and she turns around to take one last look at Palmer Station, many emotions will surface. “There are lots of things we should be thankful for here,” she said. “We’re employed, and we’re in a place where no one is sick. We’re in a place on the ocean where it’s beautiful every morning. I brush my teeth and look out the window and look at penguins.”

Even as she anticipates departure, she worries about the future of the work at Palmer and for wildlife science research in general. “Future research activity will be impacted by the pandemic. Work could slow down,” she said. “I love this place but it might be time to look for work back in Madison.”

Lipke sighed when asked what will be going through her mind on the long trip home to a place that is not as she left it. “This is our opportunity to rise up and take the challenges to move us along,” she said. “There are great new discoveries in medicine happening. I think after all this that the worse thing that could happen is we go back to normal.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us