Nelsonville's water woes: Finding nitrate pollution in wells

Residents of a central Wisconsin village are finding dangerous levels of a common agricultural pollutant in their drinking water and are left trying to filter their supplies or find new sources.

By Nathan Denzin | Here & Now

December 1, 2022 • West Central Region

“Well, it started when I bought this house,” said Tarion O’Carroll, who has lived in Nelsonville in central Wisconsin for about 10 years. He said when he first moved in and started testing, his private well saw high nitrate levels.

“They offered another nitrate screening in the village of Amherst, and I decided to get a bunch of glass mason jars, and I took them around and collected samples from all of my neighbors,” said O’Carroll. “And about half of those samples came back above 10.”

Above 10 here means more than 10-parts-per-million, the listed unsafe limit for nitrates.

If you’ve ever driven by farms in Wisconsin, chances are you’ve smelled manure getting sprayed on crops. What you might not know: The process of fertilizing farmland can leave a chemical called nitrate in the soil. Nitrates can have serious health effects if they leach into drinking water.

Nitrates are produced naturally when manure is sprayed on crops. Nitrate is necessary for most cash crops — like corn or alfalfa — to grow.

“Rainwater and snowmelt — they wash the nitrate down through the soil. And nitrate is a pretty slippery chemical. It doesn’t want to stick,” said George Kraft, a hydrologist at UW-Stevens Point. “It moves through the soil profile and gets to groundwater.”

UW-Stevens Point hydrology professor emeritus George Kraft calculated how long it would take for nitrate to reach groundwater in Nelsonville. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

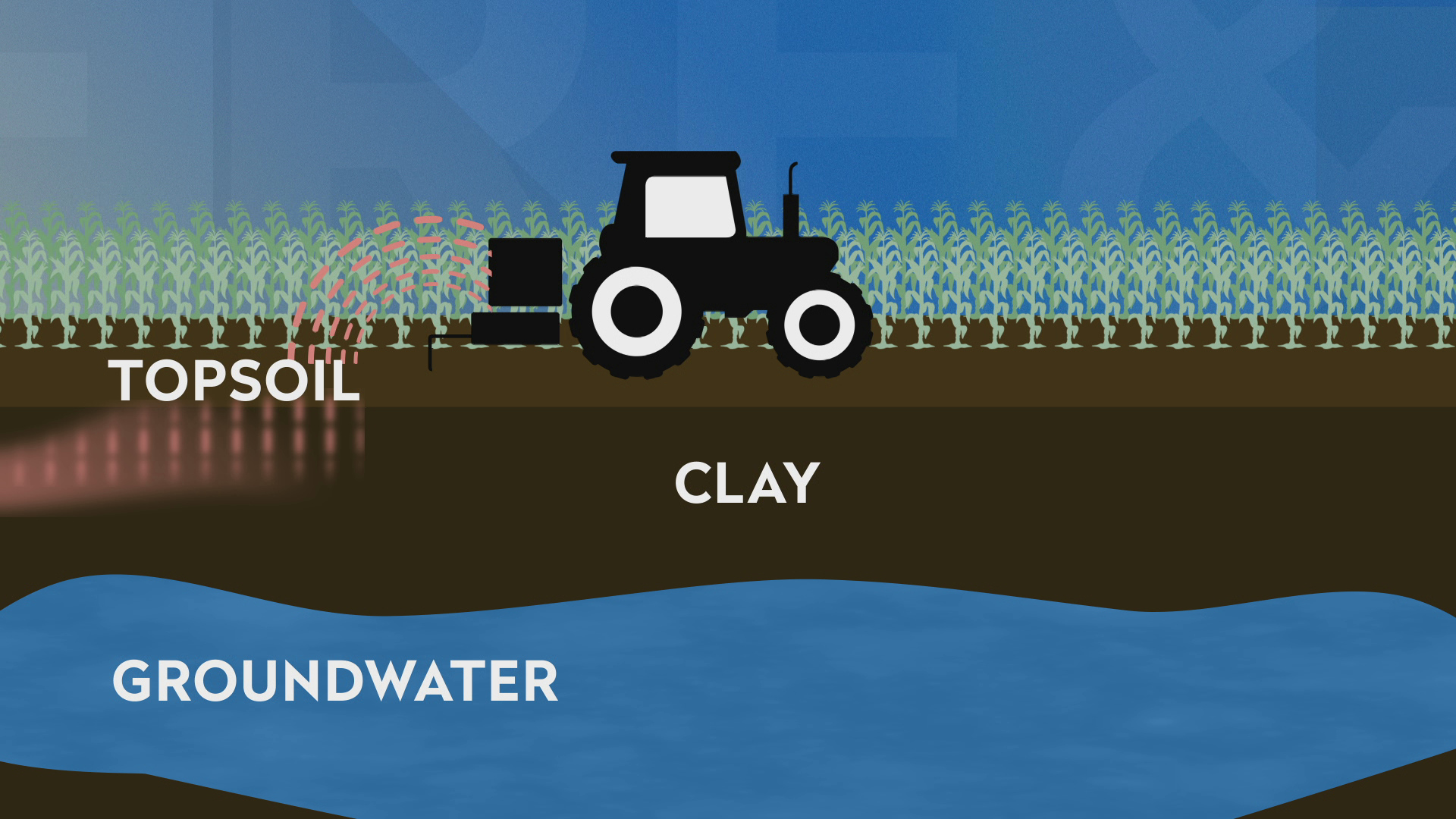

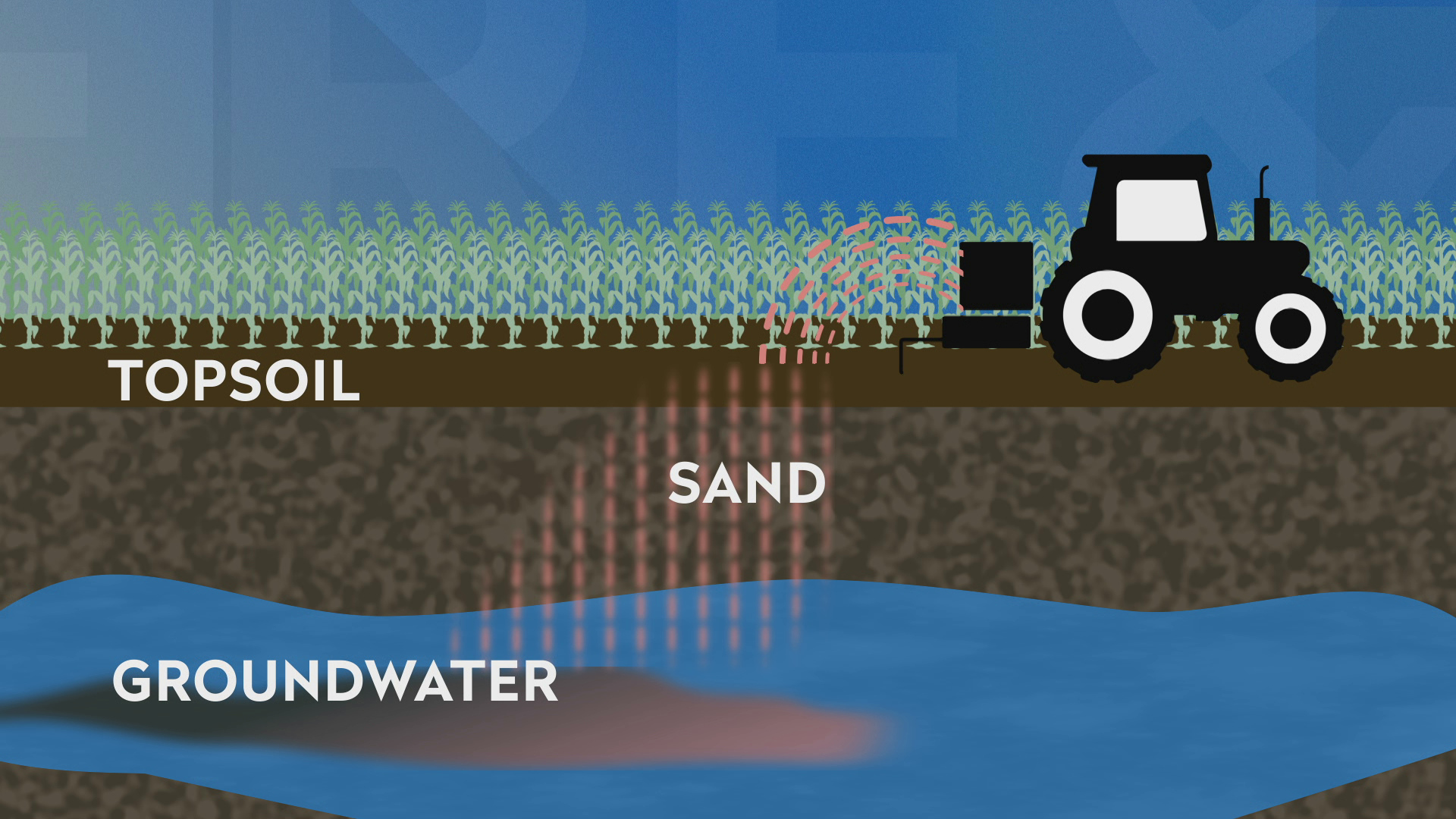

Normally, Wisconsin’s clay-rich soil filters out nitrate before the chemical can reach private wells. However, in the Central Sands region in and around Portage County, nitrates move quickly through sandy soil and infiltrate groundwater.

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services warns high levels of nitrate in drinking water can cause birth defects, blue baby syndrome, thyroid disease, and increase the risk of colon cancer. Any level above 10 parts per million can be harmful to long-term health — a threshold the O’Carroll’s water surpassed.

A tiny village of just under 200, Nelsonville has been dealing with a known nitrate problem in private wells since 2018, though it’s likely the problem has existed in the area for decades.

- An illustration shows how nitrate is less likely to infiltrate groundwater in clay rich soil. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

- An illustration shows how nitrate is more likely to infiltrate groundwater in sandy soil. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

“In 2018, the residents who live within the village in Nelsonville had started asking questions regarding their water quality,” said Jen McNelly, a water resource specialist for Portage County. “And when we started trying to find data to answer their questions, we realized that there really wasn’t a whole lot.”

Using grant money, McNelly and other county scientists sampled 60 of the village’s roughly 80 private wells, and found results that alarmed them.

About half of all water tested in Nelsonville shows nitrate levels over the safe limit of 10 parts per million, with some wells even reaching a dangerous tipping point of 30 parts per million.

If nitrate levels reach 30 parts per million, water can no longer be cleaned and made safe. However, it’s impossible to tell if your water is contaminated unless you regularly test it.

Jen McNelly secured grant money to test private wells in Nelsonville to figure out if the whole village’s wells are contaminated with nitrate. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

“It doesn’t taste any different. It doesn’t look any different. There’s no smell to it. It tastes great,” O’Carroll said.

Mark Brueggeman is one of those people who has well water above the 10 parts per million limit, and is fighting for clean water as his well approaches that 30 parts per million limit.

“We can’t go on without water. It’s necessary for anything you want to do,” he said.

Brueggman lives in a house with his wife Lois, who has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. He said after getting results that showed their water at dangerous levels, he contacted Culligan to install a reverse osmosis machine. Often called RO machines, they can filter nitrate under 30 parts per million.

Mark Bruggeman is a resident of Nelsonville who is concerned his wife, who has Alzheimer’s might drink contaminated water. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Bruggeman said his wife would often drink water from the faucet not connected to their RO machine, which could have had further impacts on her health.

“We now keep jugs of water in the fridge. And Lois pretty much doesn’t get her own water anymore,” Bruggeman said.

While RO machines are one Band-Aid solution, O’Carroll said his family has opted to get water from a public well in Lind, a tiny town about 40 miles away from Nelsonville.

“Brr, not too bad, we’re at almost 30 degrees. That’s swimming weather in Sconnie,” said O’Carroll on a water run.

“I drive there weekly and fill up my 7-gallon jugs. I usually fill up about four or five of them,” he explained.

O’Carroll said he’s tested this water to make sure it doesn’t have nitrate, and now makes the 90-minute journey about once a week.

Tarion O’Carroll was the first resident in Nelsonville to realize his private well was contaminated with nitrate. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

“In the summer, it’s not too bad. In the wintertime, it can suck. It gets all icy and they’re heavy. So it’s not something I look forward to,” he said.

The next step for the residents of Nelsonville? Find out where the nitrates are coming from.

“As I like to tell people,” O’Carroll said, “my story’s not unique.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us