How the Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast Emerged From a Sharp Political Squall

A National Marine Sanctuary established off the shores of Lake Michigan to protect and promote dozens of sites where historic sunken ships sit at the bottom followed a years-long saga of local disputes and whiplash in support at the state and federal levels.

July 13, 2021 • Southeast Region

Bound for Chicago with a hold full of Christmas trees, the Rouse Simmons was lost with all hands in a November gale in 1912. (Credit: Wisconsin Historical Society)

Encompassing nearly one-thousand square miles of Lake Michigan waters — and lake bottoms — the Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast National Marine Sanctuary marks another step in a years-long effort to help preserve dozens of underwater archaeological sites. This path to official designation was not a simple matter, however, owing to its provisions and scope, particularly for lakefront landowners. Its road also reflected shifting political dynamics over the past half-decade at both state and federal levels.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced its designation of the shipwreck coast as a national marine sanctuary on June 22, 2021. It is the fifteenth such underwater park in the National Marine Sanctuary System administered by NOAA, with four off the Atlantic Coast, two off the Gulf Coast, five off the Pacific Coast, two in the Pacific Ocean, and only one other in the Great Lakes, off the shores of Michigan in Lake Huron.

Most sanctuaries are designated for ecological reasons to protect wildlife habitat, but they can also center on underwater archaeological preservation. The first such sanctuary, which is located off the coast of North Carolina, protects the Civil War-era wreck of the ironclad U.S.S. Monitor, while the sanctuary in Lake Huron protects historic shipwrecks involved in nearly two centuries of Great Lakes commerce.

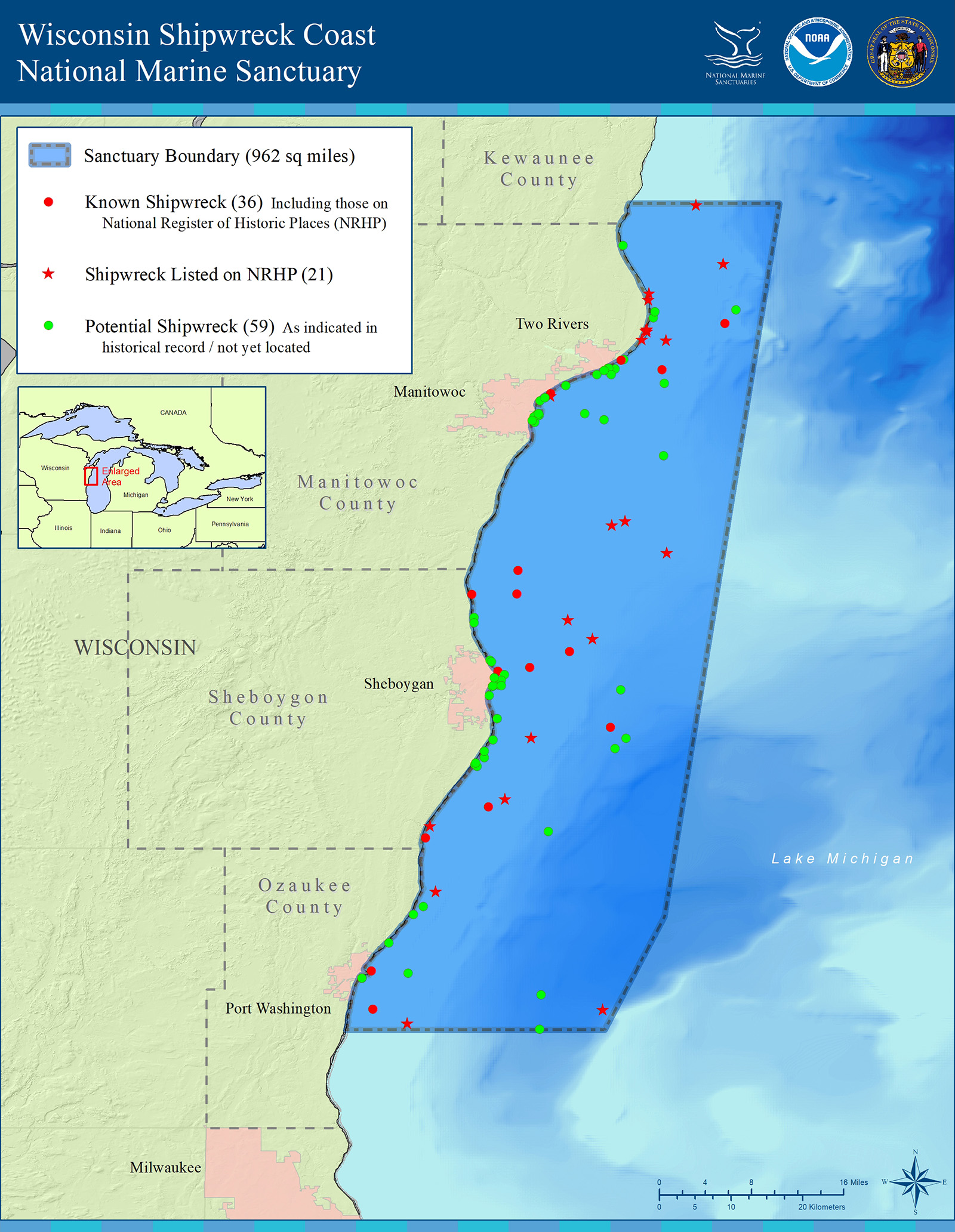

As indicated in its name, the Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast National Marine Sanctuary has a focus on archaeological protection, with its boundaries encompassing the locations of 36 known sites of historically significant vessels that went down in the 19th and 20th centuries, while the locations of potentially dozens more within the area may still be discoverable.

One example of such a shipwreck is the Rouse Simmons, known as the Christmas Tree Ship, which was built in 1868 and sank on November 23, 1912 off the coast of Two Rivers. The vessel was fully loaded with Christmas trees en route to Chicago and went down with her captain and crew. The shipwreck would be discovered nearly six decades later in late October 1971.

Owing to the cold and salt-free waters of the Great Lakes, shipwrecks that have rested at the bottom for many, many decades, and in some cases as long as around two centuries, remain in stable condition, their hulls intact and defying the ravages of time. The intention of the sanctuary is to bolster current state protections for these shipwrecks and promote their historical importance and local economies through tourism in lakeside communities and by underwater divers visiting and researching the sites.

The sanctuary spans the Lake Michigan shores of central Ozaukee County at its southern end to the southern edge of Kewaunee County at its northern end, and includes waters off the communities of Port Washington, Sheboygan, Manitowoc and Two Rivers.

The Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast National Marine Sanctuary encompasses 962 square miles off the coast of Lake Michigan and includes dozens of known and potential historic shipwreck sites. (Credit: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

The boundaries of the sanctuary extend at least a dozen miles from the shoreline along most of its span, but its exact location along the beaches, seawalls and harbors of the coast is a more technical matter. Where the lakeshore boundary starts and stops was a contentious issue during the planning process, and its location was ultimately changed from what was initially proposed.

As detailed in the final rule for the designation, the lakeshore boundary of the sanctuary is at what’s called the Low Water Datum. The Coordinating Committee on Great Lakes Basic Hydraulic and Hydrologic Data, which establishes common data references for the United States and Canada to manage their shared waters, defines the Low Water Datum as where “the lake-wide surface [is] so low that the water level will seldom fall below it.”

On Lake Michigan, the Low Water Datum is set at 577.5 feet in elevation from sea level. The final rule notes the lowest water level recorded on the lake is 576.02 feet. This definition means the boundary of the sanctuary goes up to the edge of the shoreline along Lake Michigan, but does not include any land above the water’s surface. (The Low Water Datum is not a static measure, and NOAA is considering recalculating it.) The final rule also indicates that the boundary does not include the waters of ports, marinas or harbors at Two Rivers, Manitowoc, Sheboygan and Port Washington.

A previous definition of the sanctuary’s scope set its lakeshore boundary at the Ordinary High Water Mark, which is set by the state as the boundary between public and private land given the state’s lakes and rivers belong to the public according to the Wisconsin Constitution. The Department of Natural Resources details the intricacies of this law in terms of how it applies to property taxes, land and water access, and zoning regulations.

During the deliberation process for the sanctuary, critics objected to setting its lakeshore boundary at the Ordinary High Water Mark, expressing concerns this definition would limit beach access to property owners; open beach access to the public; and prevent certain activities along beaches like cleaning storm debris, beachcombing or erecting piers and docks. In response, NOAA moved the boundary to the Low Water Datum to alleviate such concerns.

Trading vessels like the 95-foot long schooner Gallinipper linked Wisconsin coastal cities with distant markets in the 1830s and 1840s, fueling local and regional economies. (Credit: Wisconsin Historical Society)

Aside from its specific boundaries, though, what exactly does a National Marine Sanctuary allow or disallow people to do atop and within its waters? In the Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast National Marine Sanctuary, the designation zeroes in on a very specific action: prohibiting grappling into or anchoring at identified historic shipwreck sites. The idea behind this regulation is simply to protect the structures of the sunken ships from getting damaged by anchors, grapples or mooring lines connected to watercraft floating on the surface.

The ban on anchoring and grappling at historic shipwreck sites is a more specific aspect of the sanctuary’s general prohibition on “any person from moving, removing, recovering, altering, destroying, possessing or otherwise injuring, or attempting to move, remove, recover, alter, destroy, possess or otherwise injure a sanctuary resource,” which supplements an existing state statute regulating historical artifacts and field archaeology.

The designation does not prohibit fishing within the sanctuary’s waters — recreational, charter or commercial — though vessels used for fishing would not be allowed to anchor at shipwreck sites, just like any other watercraft. Nor does the designation prohibit activities like dredging or building and extending piers unless they violate the prohibition on disturbing historic shipwreck sites.

NOAA plans to establish a series of mooring buoys at shipwreck sites to improve access for visiting divers, and the prohibition on grappling and anchoring will not go into effect until Oct. 1, 2023 to allow time to put this system in place. This timeline is delayed from what was originally proposed, and reflects another shift in the planning process for the sanctuary in response to what ended up becoming a regionally controversial affair that fell in and out and back into favor through two Wisconsin governors and was temporarily shut down at the federal level.

Built in 1843 the schooner Home, is one of the oldest shipwrecks discovered in Wisconsin. (Credit: Tamara Thomsen / Wisconsin Historical Society)

What would come to be called the Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast National Sanctuary was officially proposed in December 2014, though the idea was being discussed as early as 2009. Developed through a bipartisan coalition of elected officials working with business, environmental and historical groups, the nomination was advanced by then Gov. Scott Walker on behalf of the state of Wisconsin, the cities of Two Rivers, Manitowoc, Sheboygan and Port Washington, and Manitowoc, Sheboygan and Ozaukee counties. Their goal was to establish the sanctuary to encourage more tourism and lake recreation in these communities, improve educational opportunities about maritime aspects of Wisconsin’s history, and bolster the state’s existing protections for historic shipwrecks.

A few years later, though, political squabbles over the proposal would commence in these same Lake Michigan communities, with conservative activists and landowners fearful of the federal government’s role in establishing and administering the sanctuary at odds with local business boosters seeking to promote their local economies. The quarreling revealed shifting priorities among Republican voters and officeholders, and reflected ideological cleavages on the right that would become commonplace in the latter years of the 2010s.

In April 2017, then President Donald Trump issued an executive order that was intended to promote offshore oil and gas production and also halted the designation of any new National Marine Sanctuary. This action left the future of the Wisconsin proposal in question, even as the mayors of Sheboygan and Manitowoc noted their continued interest in the Lake Michigan sanctuary.

Only a couple months later, a public discussion hosted by the Sheboygan County Republican Party erupted into contentious debate, with elected officials trading accusations, rebukes and name-calling. The county party was hosting a presentation by an activist based in Hudson, a community in western Wisconsin on the shoreline of the St. Croix River, who was opposed to the sanctuary and called it a “land and water grab” by the federal government. One party activist at the meeting called the objections “tinfoil conspiracy theories,” while an elected official pointed to the support for the sanctuary by Walker, a Republican.

However, in a letter sent to NOAA on Feb. 27, 2018, Walker pulled his support for the sanctuary, expressing concern over federal powers and state authority, among other matters. Days later, the mayors of Port Washington, Sheboygan, Manitowoc and Two Rivers issued an open letter urging the governor to reconsider that action. However, communications with Walker indicated he was planning to back away from the proposal by late 2017. Given that gubernatorial approval is necessary for a federal designation to proceed, Walker’s rescinding of his support on top of Trump’s executive order made the proposal even more uncertain.

The regional dispute over the intentions and scope of the shipwreck sanctuary was explored in detail in a Manitowoc Times Reporter investigation. It detailed the concerns of lakeshore landowners, the objection of local town board to the designation, the skepticism from a couple Republican state-level lawmakers toward the proposal and the experiences of Alpena, Michigan following the designation of Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary in Lake Huron in 2000.

As part of the designation process, NOAA solicited input about the proposal through multiple public comment sessions, in which people could share support or concerns about the sanctuary via the mail or online. It also hosted multiple public meetings to invite further feedback, including in Port Washington, Sheboygan, Manitowoc and Algoma in Kewaunee County. The final rule includes summaries of and responses to the breadth of public comments, including those raised in the local disputes over the proposal, as well as a variety of others.

Walker’s reversal attracted protests at a Republican Party function in Two Rivers in March 2018, but the issue did not play any conspicuous role in the ensuing gubernatorial race that year that ended in November with the narrow election victory of Tony Evers, the Democratic candidate.

The new governor was a supporter of the shipwreck sanctuary proposal. About a year after his election, Gov. Tony Evers held a press conference at the Wisconsin Maritime Museum in Manitowoc to announce his petition to NOAA expressing renewed support for the shipwreck sanctuary. Flanked by the mayors of Sheboygan and Manitowoc, Democratic U.S. Sen. Tammy Baldwin, and local boosters, Evers had put the proposal back in motion.

A change in presidential administrations would mark the next step in the designation process.

On Jan. 20, 2021, his first day in office, President Joe Biden issued an executive order that, among many other actions, rescinded the halt on designating new marine sanctuaries put in place nearly four years earlier. Six months after the presidential order, Evers announced the NOAA designation of the Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast National Marine Sanctuary. Following the designation’s publication in the Federal Register on June 23, it takes effect after 45 days of continuous session of Congress pending any actions taken by that body or the governor.

The partisan political dynamics persist, though, as three Republican lawmakers — U.S. Sen. Ron Johnson along with U.S. Rep. Glenn Grothman and U.S. Rep. Mike Gallagher, whose districts include the Lake Michigan shoreline areas adjoining the sanctuary — sent a letter on July 1 to Evers and NOAA reiterating worries that factored into the preceding local controversy. They requested the governor pursue establishing a state-run review of the sanctuary’s management every five years and the ability for re-proposal of the designation.

Meanwhile, Biden has expressed support for expanding federal conservation protections to American coastal and oceanic waters, and there are multiple proposals submitted for new marine sanctuaries, including several in the Great Lakes.

In Wisconsin, local officeholders and tourism boosters in Port Washington, Sheboygan and Manitowoc have applauded the federal designation, expressing their hopes the sanctuary with support and funding from NOAA will raise the profile of lake recreation in their communities and instill more interest in this mysterious and sentimental strand of submerged state history.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us