Clean Hop Program Seeks To Beat Disease And Better Bitter Beer

The flowering of craft beer over the past decade was accompanied and aided by an arms race to scale new heights of bitter flavors.

February 22, 2017

Hops at the Grumpy Troll in Mount Horeb

The flowering of craft beer over the past decade was accompanied and aided by an arms race to scale new heights of bitter flavors. At the same time, brewers developed a fascination with locally grown ingredients, paralleling a similar development in culinary culture. These two trends are merging in an effort to revive hops in Wisconsin agriculture.

Hops are a critical ingredient in brewing and provide a spectrum of flavors and aromas, essential across numerous craft styles and in the the big brands that made Wisconsin famous and still command most of beer’s market share. Properly speaking, hops are the flowers of Humulus lupulus, a perennial climbing plant native to much of the Northern Hemisphere. As bines, hops need a support system to grow – hop plants are cultivated on trellises or other structures allowing suspension that are upwards of 20 feet tall. Along with serving as a preservative, the hops themselves are memorably aromatic and provide floral and dank characteristics to beer; indeed, the plant is closely related to Cannabis, though it has not been cultivated for nearly as long.

Hops have been used for centuries, the plants grown originally in regions like Bavaria, Bohemia and southern England. Cultivation followed brewing and beer drinkers around the globe, including to portions of the northern United States. In fact, when Wisconsin was still a U.S. territory and in its early years as a state, it was a major American center of hops cultivation, blossoming alongside the nascent brewing industry in Milwaukee. But the state’s heyday as a hops region wound down in the decades following the Civil War. By the early 20th century, hops agriculture had shifted west into Oregon, Washington and Idaho, states where numerous cultivars of the plant are still widely grown today.

A glut in the market and other business challenges contributed to the decline of hop cultivation in Wisconsin, but what ultimately ended it was a series of blights caused by fungus and insects. A plant disease called downy mildew provided a killing blow, and it has remained a threat ever since.

Demand for hops is growing, though. The spectacular rise in popularity of craft beers like pale ales, India pale ales, imperial (or double) IPAs, triple IPAs, black IPAs, imperial reds, and so on and so forth has created a need for more of these flowers, both fresh and crushed and compressed into pellets for the brew kettle. Indeed, brewers experienced a brief hops shortage in 2007-2008 and another is looming a decade later, both thanks to the ravenous appetite for bitter beers. Meanwhile, craft brewers are increasingly interested in sourcing their supplies locally.

Together, these interests have opened the door for a revival of hops cultivation in Wisconsin. In recent years, businesses like Gorst Valley Hops and the Wisconsin Hop Exchange have been trailblazers in encouraging farmers to take a risk in growing these plants while connecting them to breweries hungry for homegrown ingredients. But downy mildew continues to be a challenge for hop growers, as do powdery mildew, viruses and a variety of other diseases.

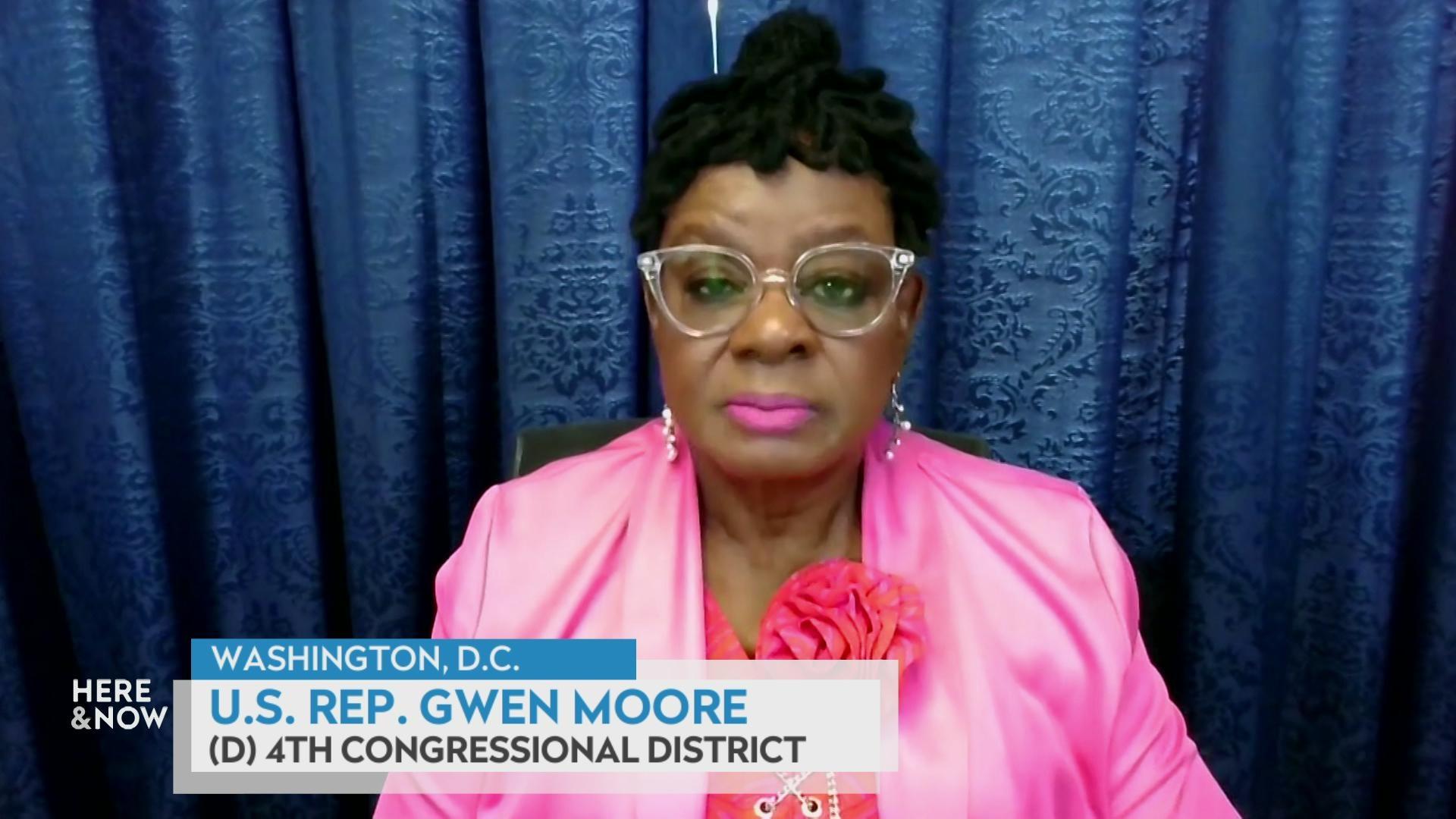

In an effort to re-establish a hops industry in Wisconsin amid the threat of blight, scientists are working with growers to cultivate hop plants free of disease and cultivate new varieties. Jerry Clark is an agricultural agent with the University of Wisconsin-Extension Chippewa County. In a Feb. 14, 2017 interview on Wisconsin Public Radio’s Central Time, he discussed the Clean Hop Program, which is seeking to improve the plant stock growers in the state use.

“Basically, it’s hard to get pathogen-free plant material for growers to plant into their new hop yards,” said Clark. When hop growers purchase plantlets or rhizomes to start or expand cultivation, he explained, they could wind up getting a pathogen as part of the package.

“Downy mildew is basically the disease that drove the hop industry out of Wisconsin,” said Clark. The fungus favors moist conditions, which is one reason why hops are primarily cultivated in areas of the northwestern U.S. that are in the rain shadows of the coastal and Cascade mountain ranges. “That climate is a just a little bit lower in humidity than here in Wisconsin,” he noted.

But even hop plants acquired from the Pacific Northwest can harbor downy mildew and other diseases, which is why Clark and others in Wisconsin are looking to provide a “clean” source for growers.

“It’s hard to get pathogen-free plant material for growers to plant into their new hop yards,” he said.

The Clean Hop Program is an ongoing collaboration between researchers at the UW-Madison Department of Plant Pathology, Extension agricultural agents in several counties and farmers interested in getting into the hop business. Clark explained that it has several focuses, including evaluating high-yield and high-quality hop varieties, and assessing which cultivars are well-suited to Wisconsin growing conditions. The goal of the program, now several years along, he noted, is to “develop an economically sustainable system for producing pathogen-free planting stock.”

As part of their contribution, UW vegetable pathology scientists researching hops have conducted tissue culture and standard propagation, Clark said, trying to produce disease-free planting material.

“That’s why we call it the Clean Hop Program,” Clark said. Hop growers “can be guaranteed that this is disease free material and get off to a better start.”

The program is working with about a dozen cultivars of hops, Clark noted. These varieties include the widely in-demand Cascade, along with Mount Hood, Willamette and Hallertau hops.

“Maybe we’re up to a few more,” said Clark. “I know the researchers at UW-Madison are picking up a few different varieties every year.”

Most of the varieties the project is researching in in Wisconsin are available to interested producers, he noted, with some being grown on a trial basis.

The program has encountered challenges intrinsic to agriculture, namely weather. For example, a late spring frost in May 2016 struck test hops in Chippewa County, with the cold temperatures damaging a couple of weeks of growth on the plants.

Clark estimates there are about 400 acres of hops currently being cultivated across Wisconsin. And that number is gradually increasing.

“As people add a few acres every year, we’re seeing the amount of hops growing in the state continuing to climb,” he said.

As it takes several years for hop plants to really start producing usable flowers, the Clean Hop Program is gearing up to assess soil conditions, yield rates and the quality of their harvests.

“We’re looking at a number of different projects with hops since it’s had kind of a renaissance period here,” said Clark, “and hoping we can provide some good data for the growers out there.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us