Baraboo Logger Has Had to Saw His Business to the Bone

Mike Wilm is cutting wood even as he cuts payroll. How long can he keep it up?

By Andy Moore | Here & Now

April 14, 2020

The opportunity to run the dog through the woods was too good to pass up. And so it was that I took up my neighbor Jordy Loeb’s offer to take our black lab EmmyLou out to his rural property. It was a sunny, early Saturday afternoon about, oh, 100,000 years after the retreat of the Labrador Ice Sheet that divided the edge of what became the Arlington Prairie—holding some of the richest soil in North America—from the sandy ground that passes for soil in the southern part of Columbia County.

Loeb’s father, a Milwaukee attorney, bought the land in the 1950’s: over 300 acres of rise and fall that had been logged to death. Leonard Loeb, with guidance from the DNR, planted pine trees “plantation style,” in rows with stock that was trucked down from Vilas County where the sandy soil is nearly identical. In this format, every 20 years a row is harvested until a random cut can happen and the forest assumes a sustainable eco-system on its own. The property is currently in the midst of a 20-year clearance.

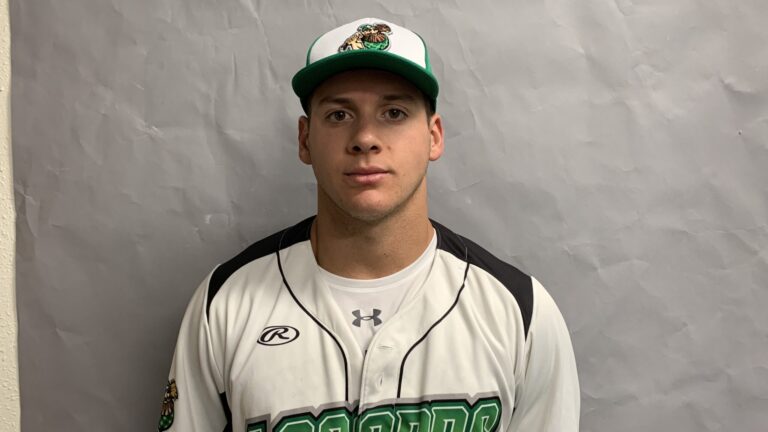

The land is zig-zagged with logging trails, perfect for hiking and for dog skee-daddling. EmmyLou skittered ahead on the path, occasionally darting into the dense woods on matters of extreme canine importance. Off to the side appeared an enormous metal monster of a machine, a giant tree cutter which stood unattended, at rest and still. Its owner and operator, Mike Wilm, appeared a half-mile up the trail munching a sandwich on lunch break, sitting on the tailgate of his utility vehicle. We stayed about 25 feet apart.

Wilm scoffed when the operation of the machine was mentioned. “I need a cheat sheet to make her go,” he said. That’s because Wilm had to lay off his primary machine operator at the end of March together with four other full-time employees out of a total workforce of 10, at his Baraboo-based Hack Away Forest Products. “It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life,” he said. The market for wood he cuts is at a COVID-19 stand still. “I’ve never had to lay people off in fear of not having income in the foreseeable future,” he said.

Wilm started harvesting firewood for pocket money while he was still in high school. In 1983 he made his first serious machine purchases that allowed him to “dabble in logging.” He said his “firewood dream” has grown and expanded to include a customer base in Chicago as well as in Wisconsin. Products now include pulpwood, bolts (logs cut into specific, shorter length), and logs for the lumber mill. “I buy the standing timber and market it to the different markets.” Options that are now closed down.

Costs of employee insurance ($100, 000 per year) are unchanged. Maintenance on his machinery including the big TimberPro cutter parked down the hill, continues. Business loan payments on purchases are ongoing. Wilm said the TimberPro tree cutter alone cost $720,000 new.

Then there are the usual, economic challenges that come with the logging business, setbacks that Wilm speaks to with the unselfconscious candidness of a woodsman. “We’ve faced so much bull shit with global markets and trade wars and shitty weather. You try to look for light at the end of the tunnel.”

Right now that light resembles relief in the form of state and federal dollars. Wilm and his wife have had many discussions with their accountant and banker. Hack Away has applied for the Payroll Protection Program as well as the COVID-19 Small Business Administration (SBA) loan. “The applications were short and easy to fill out but I had our accountant fill them out as he added additional back-up of supporting documents,” he said. “The bank tried to upload a batch on Friday but the system was so overloaded with applications it kept shutting them down.” Wilm said it took the bank the entire weekend of non-stop attempts to get the batch of applications submitted.

I asked Wilm how long the wait will be to see if relief is coming. “My bank says it could be a couple of weeks, but it’s unknown to anyone at this time.” He compares the helplessness he’s experiencing to another time and a different American crisis. “It has an every man for himself feeling like on 911.”

So Mike Wilm’s struggles continue. He continues to struggle with the controls on the TimberPro. He struggles to make his limited payroll and has relied on “incredibly reliable” hourly help from Amish workers, over from the Westfield-Coloma area, who work chain saws on the steep, hillside spots where the big machine cutter cannot access. And he struggles, as he says he always has, with what he says is an unfair and inaccurate impression the general public has when it comes to loggers and their work–work that amounts to Wisconsin’s second-largest industry after tourism.

“People don’t perceive the logger as a very nice guy,” he said. “But essential? What’s essential? Especially these days? Toilet paper. Boxes. Pallets.” The fact that some people think of loggers as environmentally unfriendly is a particularly deep cut to Wilm. He said for most logging operations the opposite is true. “We help sustain. We weed the garden,” he said, adding that he understands the emotional attachment people have with trees. He has his own wooded property and had to have the forester come mark it for a managed forestry cut because, “I was too emotionally attached to this tree or that one,” he recalled. “After he marked it I had to go about cutting it as though it belonged to someone else.”

“People don’t perceive the logger as a very nice guy,” he said. “But essential? What’s essential? Especially these days? Toilet paper. Boxes. Pallets.” The fact that some people think of loggers as environmentally unfriendly is a particularly deep cut to Wilm. He said for most logging operations the opposite is true. “We help sustain. We weed the garden,” he said, adding that he understands the emotional attachment people have with trees. He has his own wooded property and had to have the forester come mark it for a managed forestry cut because, “I was too emotionally attached to this tree or that one,” he recalled. “After he marked it I had to go about cutting it as though it belonged to someone else.”

Before leaving him to finish his lunch, I asked Wilm if he was afraid of catching COVID-19. He chuckled, shaking his head as he offered a piece of beef jerky to EmmyLou. “If I get it anyone could,” he said. He waved his hand in air. “This is the most social contact I’ve had in weeks.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us