Nelsonville's water woes: A fight over sources of nitrate

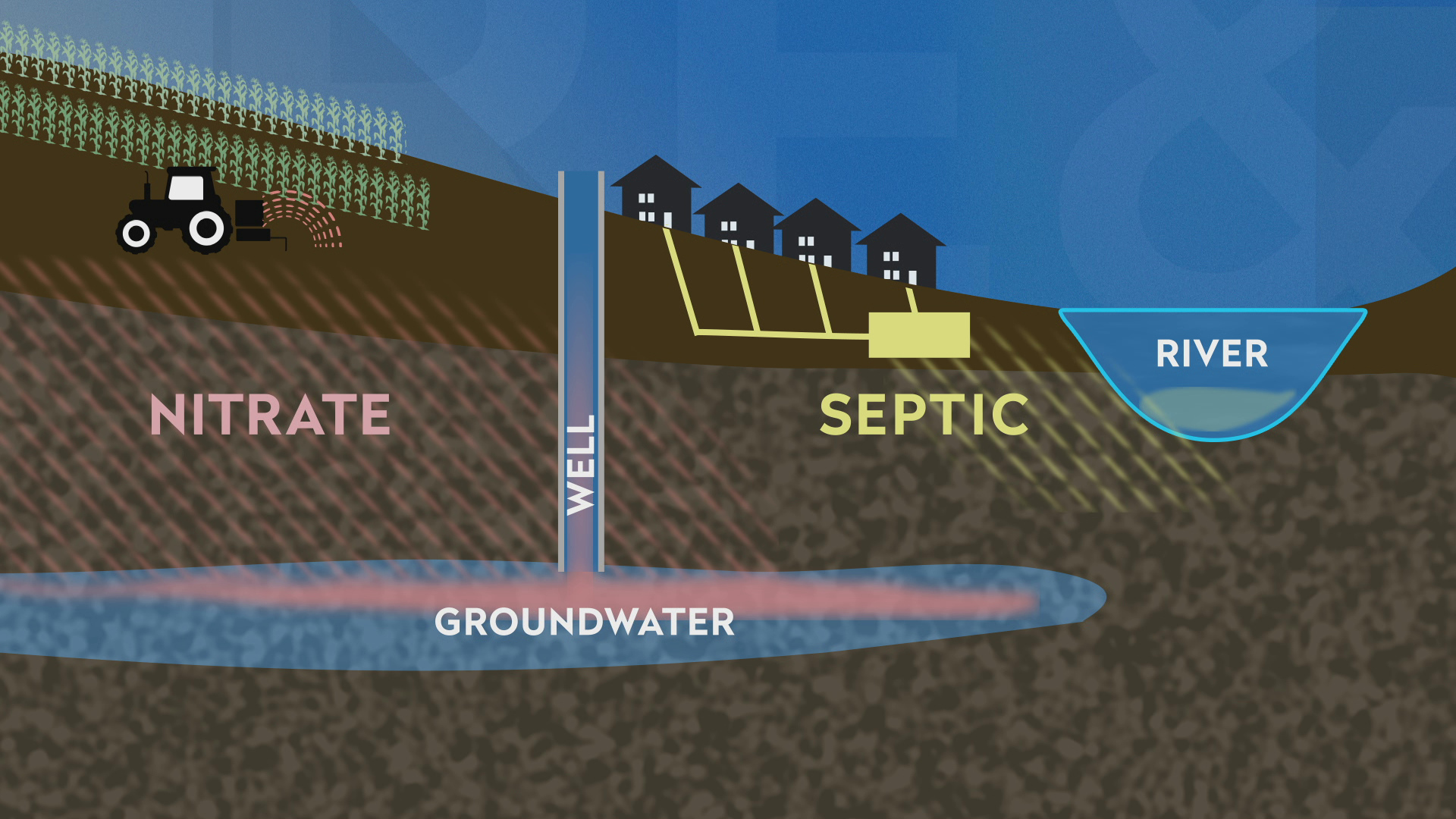

Contamination of well waters by a chemical common in manure and septic systems has residents of a rural community in central Wisconsin arguing about its causes and finding appropriate solutions.

By Nathan Denzin | Here & Now

December 8, 2022 • West Central Region

“It doesn’t taste any different. It doesn’t look any different. There’s no smell to it. It tastes great,” Tarion O’Carroll said about the water pouring from his kitchen tap.

But what he found out was his family’s private well water had unsafe nitrate levels, a problem residents in the small village of Nelsonville in Portage County learned about in 2018.

The two contributors under the microscope: manure from farm animals and septic systems that leak human waste.

Portage County water resource specialist Jen McNelly said scientific water testing showed nitrates are largely coming from agriculture.

“There’s some role that septic systems are playing, but probably not by and large the largest contributing source of it,” McNelly said.

Jen McNelly, water resource specialist for Portage County, has found agricultural practices have had a larger impact on nitrate contamination in Nelsonville’s well water than septic systems. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

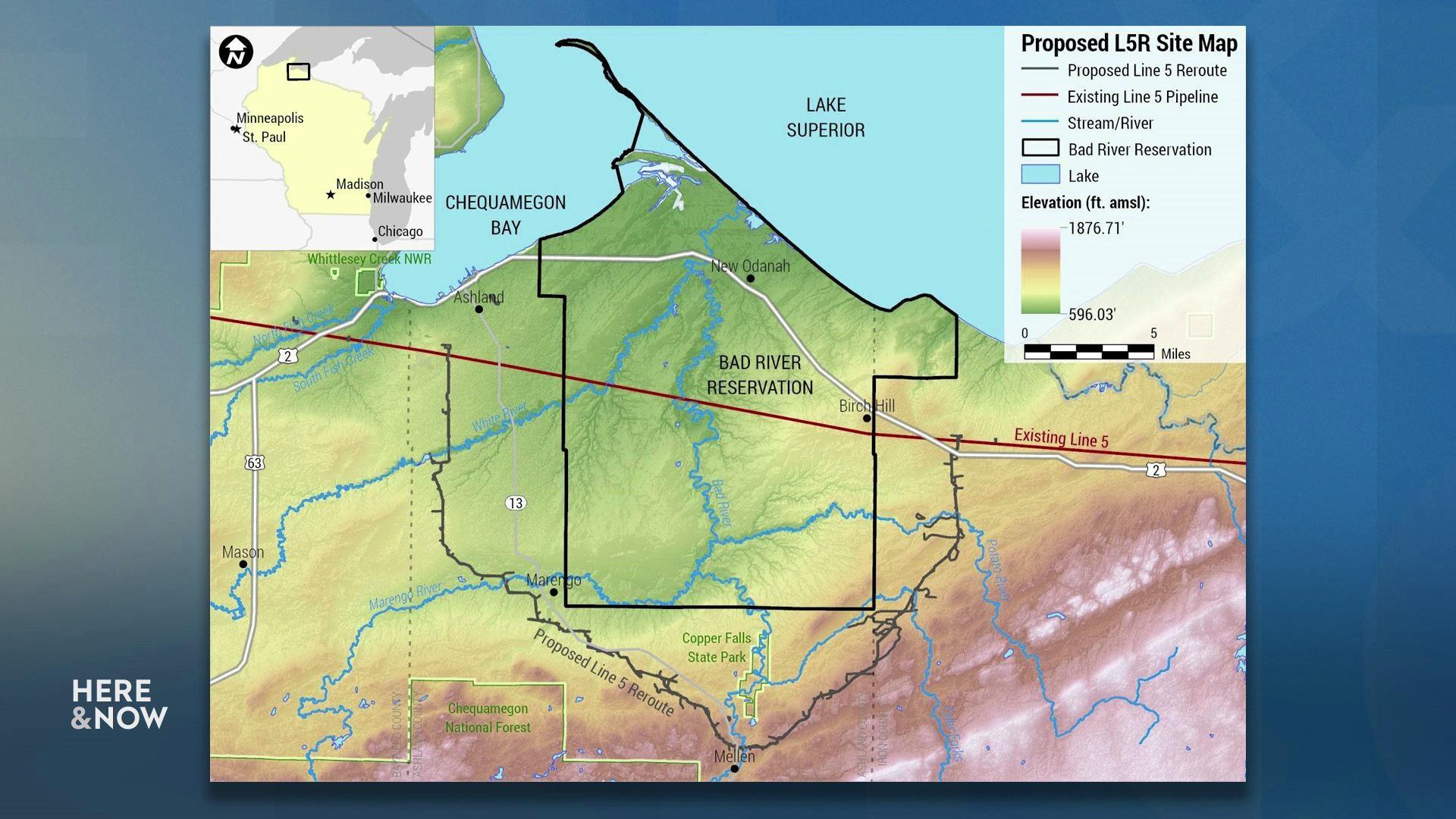

Enter Gordondale Farms, a concentrated animal feeding operation, or CAFO, of about 1,200 cows and 5,000 acres just outside of Nelsonville. Its owner, Kyle Gordon, and his family have been farming this land since 1900.

“Well, I think we have to be really careful when we talk about ‘the science shows,’ where we would really like to see more research on that. They seem to have dismissed septic,” said Gordon.

Gordon added he does accept farming can impact drinking water, but he’s not convinced his own farm is.

“Our take on the nitrates — from our standpoint — is our farm has always had a nutrient management plan since 1981. We followed every regulation that’s been put forth to us,” Gordon said. “So to be honest, it’s quite a puzzle. Like, where’s it coming from? Like, what is the deal?”

Kyle Gordon is the owner of Gordondale Farms, a concentrated animal feeding operation located on the outskirts of Nelsonville — he isn’t convinced his farm is solely responsible for nitrate contamination in the area, and points to the effects of septic systems. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

By all accounts, Gordondale Farms has followed every DNR nitrate regulation, and in recent years has gone further. In most plots near the village, Gordon said his farm now plants alfalfa or Italian ryegrass, which soak up more nitrate in soil than corn.

County water officials said despite Gordon’s efforts and abiding by nitrate regulations — agriculture remains the likely culprit, at least in part because DNR rules don’t account for the sandy soils in the region.

Also, water flow itself affects what kind of waste — agricultural or septic — is ending up in wells.

Research has found septic system waste doesn’t infiltrate deep enough in soil to contaminate to groundwater. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Pete Arntsen, a hydrologist for the regional consulting group Sand County Environmental, explained how it works.

“Because of the hydro geology, that water from the septic system passes above all the wells and discharges to the Tomorrow River and really isn’t the issue,” he said.

Because wells draw from groundwater, contamination can come from miles away and take years to end up in the drinking water.

Agricultural practices like the ones Gordon has turned to can reduce the nitrates in private wells. But according to George Kraft, an emeritus hydrologist at UW-Stevens Point, that can also take years — even decades.

“I think we’d be almost out of the woods, so significantly in eight, 10 years and maybe mostly or entirely in 20 to 25,” said Kraft.

- Hydrologist Pete Arntsen has conducted extensive research on septic system pollution, and says it doesn’t pose much of a problem in Nelsonville. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

- UW-Stevens Point professor emeritus George Kraft doesn’t expect to see major reductions in nitrate around Nelsonville for at least 8-10 years. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

In August, the DNR told Gordondale Farms it had to install three monitoring wells on his property. Gordon is fighting that in court. A decision on whether Gordon should pay for construction of these wells is expected in court within several months.

For its part, the village also hopes to use a quarter million dollars in federal funds to install its own monitoring wells.

And so-fights over the monitoring wells and who’s at fault for the contamination is fracturing the community.

“I would say that a lot of people are angry,” said Lisa Anderson, a clean water advocate who lives in Nelsonville.

“We’ve been accused of having an agenda. We’ve been targeted on social media,” she added.

Nelsonville resident Lisa Anderson has been a prominent advocate among those in the community pushing for cleaner water. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Tempers are definitely high.

“I’m sure everyone knows what the finger is, right? We either get a plug nose or we get a finger,” said Gordon. “The sad part … We’re busy fighting each other.”

“I understand clean water is everyone’s right. But if you’re going to live out here in paradise, it’s your responsibility to take care of your well and take care of your septic system,” Gordon added.

“To spend $10,000 on a well for most of us is a major expense, and many can’t afford it. And I think many of us feel like, why should we have to?” said Anderson.

Gordon also said he can’t afford the monitoring wells he’s ordered to dig, and it could put him out of business. Village residents say they don’t want that — they just want clean water.

Nelsonville resident Tarion O’Carroll says the Wisconsin DNR should consider new regulations for the Central Sands region that would protect groundwater. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

“I’m not anti ag. We’ll just get that out of the way,” said O’Carroll. “It’s not it’s not the farmer at all. They’re working as hard as they can to make a good living. And that’s fair.”

Still, Nelsonville residents say the state should impose new regulations for the Central Sands region to protect the groundwater.

“The rules are the problem. So the DNR needs to step up and fix this issue in my mind,” said O’Carroll.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us