Unhoused and underserved: Milwaukee sees increase in homeless resident deaths

At least 52 Milwaukee County residents died while experiencing homelessness in 2021 — a significant increase that's likely undercounted, officials say.

Wisconsin Watch

December 5, 2022 • Southeast Region

The Milwaukee County Medical Examiner's Office recorded 52 deaths of people experiencing homelessness in 2021, more than double the 21 deaths recorded in 2018, according to data provided to Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service. (Credit: Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service)

Milwaukee is seeing a spike in deaths among people who lack a regular place to live but don’t meet the standard definition of homelessness.

The Milwaukee County Medical Examiner’s Office recorded 52 deaths of people experiencing homelessness in 2021, more than double the 21 deaths recorded in 2018, according to data provided to Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service.

Meanwhile, data for January and February show that the county is on pace for as many or more such deaths in 2022. The Medical Examiner’s Office did not respond to a request for more recent data.

But the available data likely underrepresents deaths of people who lack housing, officials said.

The leading cause of the deaths: Substance abuse, particularly involving opioids like fentanyl.

The deceased include two people who had connected with Street Angels Milwaukee Outreach, which has aided unhoused Milwaukeeans since 2015. Aiming to build a rapport and understand the services residents need, organization staff three times a week hand out items that meet basic needs, including sack lunches, hot meals and hygiene items.

“We just had a gentleman murdered downtown,” said Dan Grellinger, the group’s homeless outreach specialist. “It shook people up.”

Counting methods are inexact

The lack of standardized methods for determining who lacks housing when they die creates challenges for those serving the population.

Karen Domagalski, operations manager for the Medical Examiner’s Office, suggested that the data her office keeps likely undercounts deaths among people who are homeless.

If someone dies at a shelter, for instance, the shelter’s address might be recorded as the place of death, meaning that it would not be readily apparent that the person was experiencing homelessness.

“We had a homeless person die … in an abandoned building. He may have been an overdose, or it may be hypothermia,” she said. “Family said he was homeless, but an address was provided, so he will most likely not show up on any ‘list’ of homeless deaths.”

Service providers also struggle to track the unhoused population, and that can affect the resources they offer. Most federal funding goes only to assist people who are either “literally” or “chronically” homeless, as defined by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, or HUD.

This encompasses people who are living on the street, a “place not meant for habitation” or in a shelter on a short-term basis.

As government entities and nonprofits carry out their funded work, people who lack stable housing but don’t meet the technical definition of homelessness often go unseen and unserved.

HUD-funded assistance programs, for example, include four categories of homelessness:

- People who live in a place not meant for human habitation, in an emergency shelter, in transitional housing or who are leaving an institution where they temporarily lived.

- People who are losing their primary nighttime residence.

- Families with children who face housing instability and are likely to continue in that state.

- People who are trying to leave domestic violence and have no other residence.

“There are pockets of the community who are living in the shadows of the system who are suffering,” said Eric Collins-Dyke, assistant administrator of Supportive Housing and Homeless Services at the Milwaukee County Housing Division.

“We have to honor this gap in the system and this piece that we are missing. We have to look for more resources. We shouldn’t have to say that we are mandated to do something.”

Emily Kenney, director of systems change at IMPACT, the parent organization of IMPACT 211, a free helpline and online resource directory that connects residents to services, echoed this need.

“Since 2019, we have been paying more attention to those folks that are unstably housed and try to provide services beyond keeping them from coming into the homelessness systems … beyond what HUD funds us to do.”

Stable housing helps prevent deaths

Stable housing – particularly shelter and permanently subsidized housing – remains one of the most effective and recognized ways of preventing deaths of people experiencing homelessness.

Without this basic need being met, “They freeze to death. They die from heat in the summer. They have multiple health conditions,” said Sherrie Tussler, who serves as the executive director for Hunger Task Force.

Advocates and homeless services professionals say they are aware of the lack of readily accessible shelter and housing.

“There’s quite a lot of people who would go into shelter but can’t,” Grellinger said.

Stephanie Nowak, the community intervention specialist lead for the Milwaukee County Housing Division, pointed out that those with substance abuse or mental illness often feel less accommodated by shelters, further complicating efforts to get them off the street.

“We understand why oftentimes people who are street homeless don’t want to use shelter or why that is not a good or right option for them, and we acknowledge that, and we work with them for what would be a better option,” Nowak said.

Grellinger tells people who want help finding long-term housing to expect a wait.

“We generally tell people – best case scenario – if you get into 211 and get into a housing program and fill out an application and find a landlord, it’s six or nine months out,” he said. “It takes a long time.”

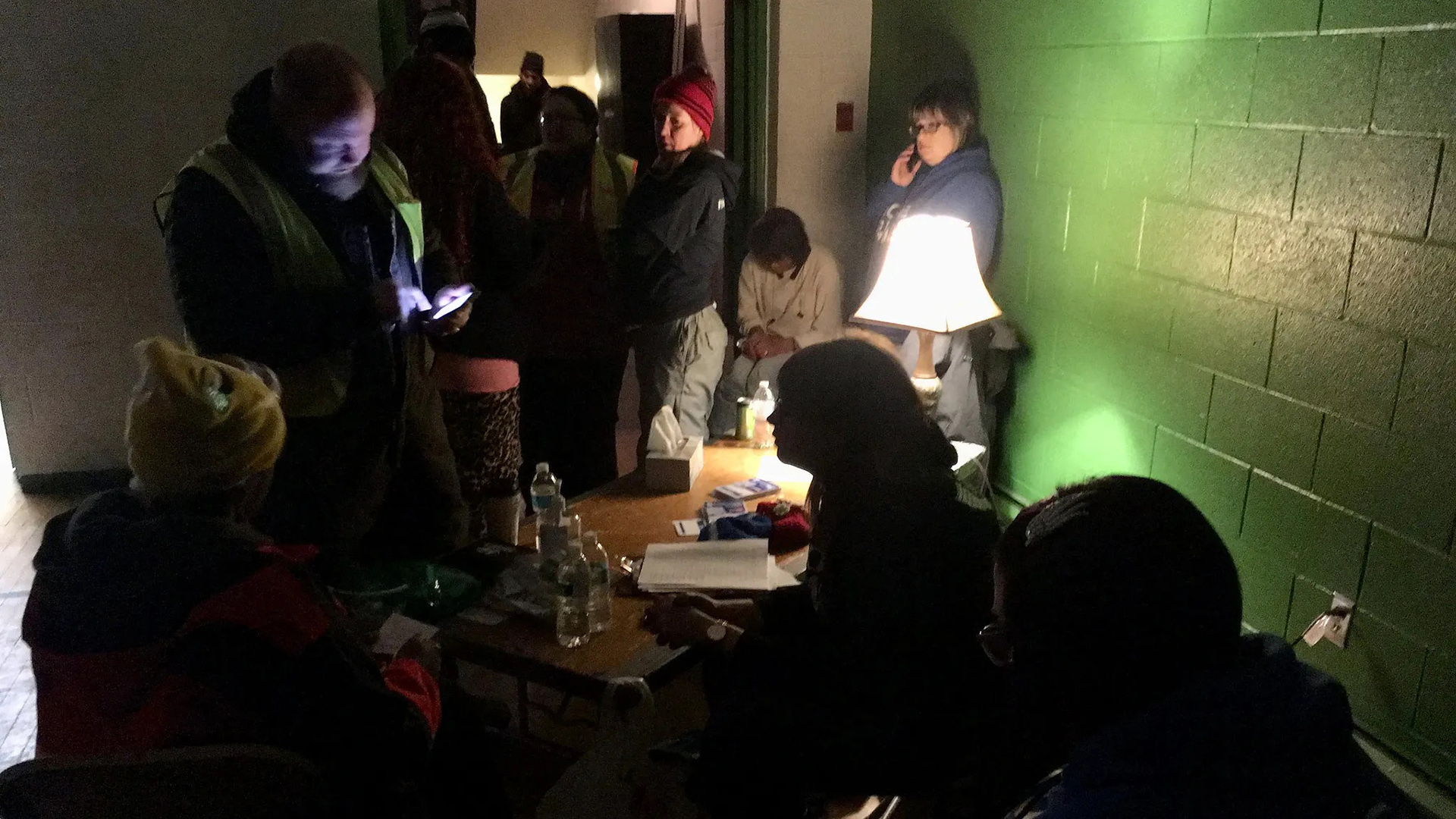

Volunteers at the Street Angels Milwaukee Outreach emergency shelter at Ascension Lutheran Church speak with a guest near a lamp in the gym where guests slept in 2018. Milwaukee is seeing a spike in deaths among people who lack homes, including the recent deaths of two people who had connected with Street Angels. (Credit: Elliot Hughes / Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service)

As the city grapples with its opioid crisis, residents experiencing both homelessness and addiction need housing and accessible treatment to lower their risk of preventable death.

Shelly Sarasin, the co-executive director of Street Angels, reported consistent bottlenecks in connecting people to certain drug-related resources.

“Fentanyl is really present in our community. Though we have a lot of harm-reduction resources, we don’t have a lot of facilities that are easy to get into.”

A facility catering specifically to those with opioid addiction would also crucially help those who are seeking treatment, said Gina Allende, the health promotions manager at UMOS, which provides a variety of services to Wisconsin’s migrant and seasonal workers and other diverse populations.

The one detox clinic run by the county serves people seeking services for many different types of addiction but “when people have opioid addiction, it comes right away with withdrawals … and they are concerned they won’t get medication right away and that they are going to suffer,” Allende said.

Location of treatment facility an obstacle

But people experiencing homelessness run into a range of obstacles that limit treatment access.

Those include location.

Milwaukee County funds just one facility that provides residential detox and medication-assisted treatment — the use of medications such as buprenorphine or methadone to help suppress withdrawals and limit craving. That’s First Step Community Recovery Center at 2835 N 32nd St.

The facility is in the North Side Milwaukee neighborhood of Sherman Park, so patients living on the South Side often “don’t feel comfortable” when they find out where the facility is located, Allende said. “It would be a lot easier if people could just walk over there.”

Patricia Gutierrez, alcohol and drug abuse services director at IMPACT, said she understands this obstacle.

“When someone calls us, we usually ask them ‘is there someone we can call for you, is there a family member, a friend we can call for you,'” she said. “If it’s serious and life-threatening, we’re going to call an ambulance or police to see if they can take you down there. We just want to make sure the client gets there, and we use whatever avenue we can to get them there.”

UMOS and Street Angels regularly collaborate with the Milwaukee Fire Department via its Milwaukee Overdose Response Initiative, or MORI, to help bridge this transportation gap. When UMOS or Street Angels staff encounter someone who wants treatment, they will call MORI to help arrange a ride.

Opioid settlement could help

Still, advocates and homeless services professionals cited two reasons to be hopeful for progress.

The first is the $400 million in opioid settlement money Wisconsin will receive over the next 18 years. This money has been earmarked for prevention programs, residential treatment and medication-assisted treatment, among other programs.

The settlement money will also fund harm reduction and overdose prevention resources, including naloxone and fentanyl test strips. The growing availability of such resources offers people working in the field another source of hope.

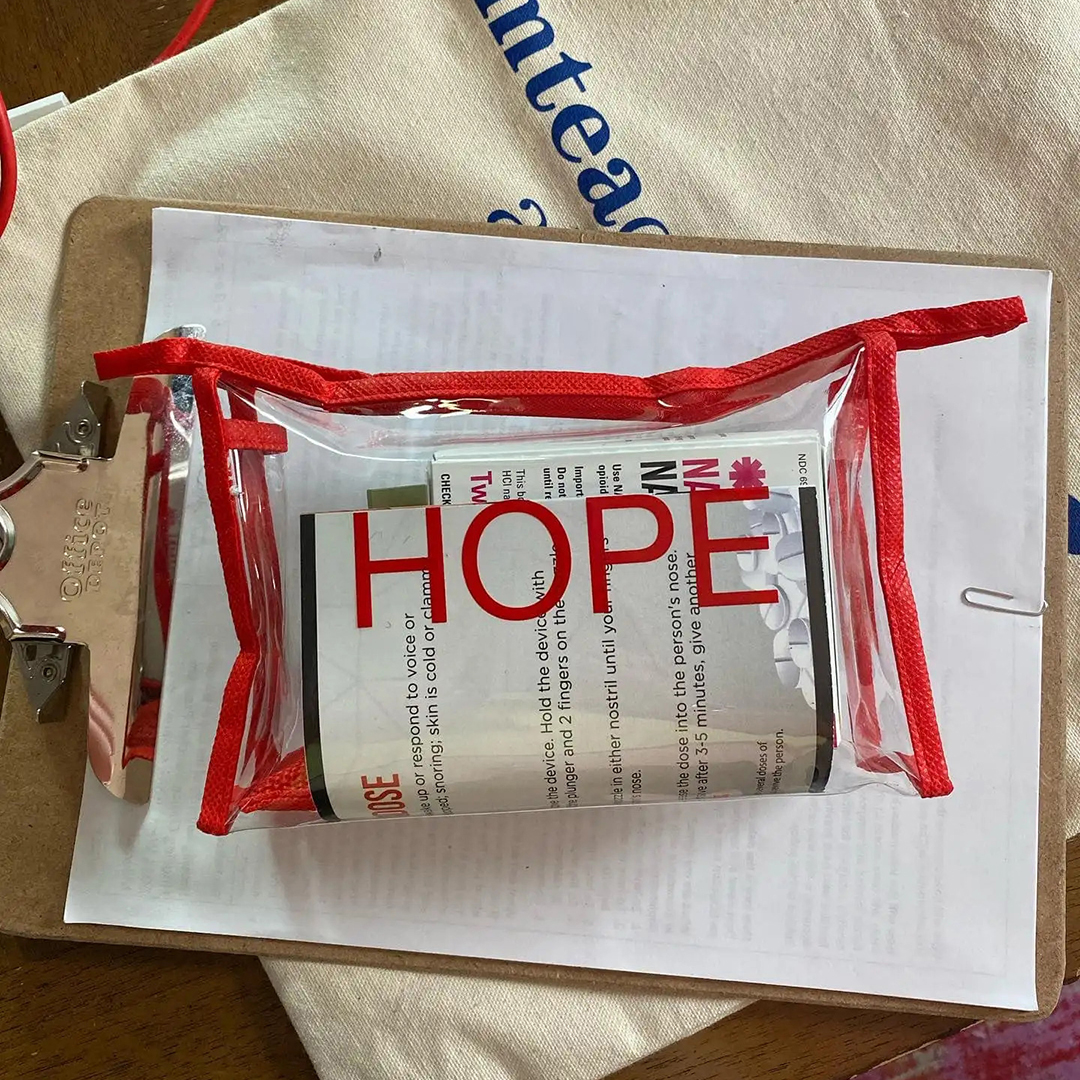

- The outside of a “hope kit” is shown. The kits were developed by the Milwaukee Overdose Response Initiative, a partnership between the Milwaukee Health Department, the Milwaukee Fire Department and other groups that seeks to decrease the chances of drug overdoses.(Credit: Courtesy of MKE Overdose Prevention)

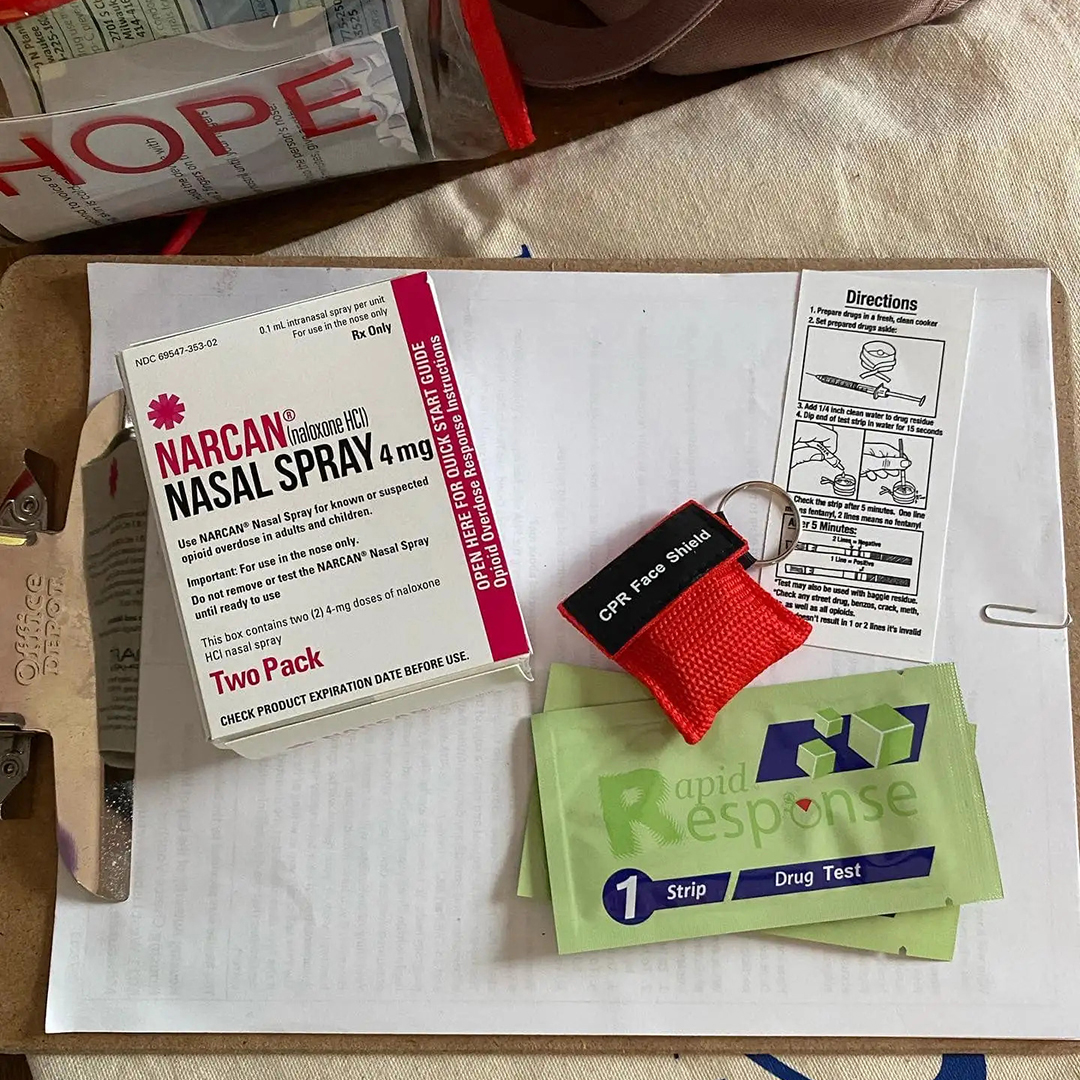

- The contents of a Milwaukee Overdose Response Initiative “hope kit” are shown, including Narcan nasal spray to temporarily reverse the effect of opioids, CPR face shields and fentanyl testing strips. (Credit: Courtesy of MKE Overdose Prevention)

Harm reduction refers to practices that aim to limit the dangers involved in behaviors that pose risks to one’s health, such as drug use or sex work — a contrast to zero-tolerance policies.

UMOS, Street Angels and MORI distribute fentanyl test strips and naloxone, which service providers call life-saving resources.

Milwaukee Fire Department Capt. David Polachowski, who oversees MORI, helped develop its “hope kits,” which include naloxone, CPR face shields, fentanyl testing strips, a card for Narcotics Anonymous and contact information for MORI and UMOS.

“Our success is — are these people still alive? Because then there’s the potential for us, or anybody, to assist. That’s a win,” Polachowski said.

A version of this story was originally published by Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, a nonprofit news organization that covers Milwaukee’s diverse neighborhoods. The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch collaborates with Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us