Wisconsin Pride – Part One: Hidden Histories

Announcer: This program is brought to you by the combined resources of the Wisconsin Historical Society and PBS Wisconsin.

§ §

Dick Wagner: We define ourselves as a society by the stories we tell. If we don’t tell the stories of LGBT history, then we’re basically erasing them as if they didn’t exist.

Narrator: The history of Wisconsin has long been told from a particular point of view, one that has often concealed LGBTQ+ people.

Scott Seyforth: As I came out as a gay man, I looked for those stories. I have to tell you, those were hard to find.

Ashley Brown: There can be a tremendous silence about individuals and communities. That silence has not been accidental.

Narrator: Long hidden, these are stories of extraordinary Wisconsinites.

Josie Osborne: They’re people who blazed a trail, people who did great things.

Michail Takach: The resilience of these people in a world that feared them, outlawed them.

Narrator: But no longer would they be hidden. A movement was born. A stance on freedom was made.

Víctor Macías-González: We organized, we learned, we changed things.

Dick Wagner: These Wisconsinites were liberating themselves. Somehow, despite the oppression and homophobia, they had a place.

Narrator: Their stories reveal a larger tapestry of our collective past.

Will Fellows: It’s not just LGBTQ history or queer history. It’s also just Wisconsin history.

Narrator: Wisconsin Pride.

Announcer: Funding for Wisconsin Pride is provided by Park Bank, S.C. Johnson, Greater Milwaukee Foundation, Evjue Foundation, the charitable arm of the Capital Times, CUNA Mutual Group, New Harvest Foundation, West Foundation, Paula Bonner and Ann Schaffer, La Crosse Community Foundation, MG&E Foundation, Rogers Behavioral Health, with additional support from and with support from Focus Fund for Wisconsin Programs, and Friends of PBS Wisconsin.

§ §

Dick Wagner: We’ve been here all along, and nobody knew it. There is a long LBGT history in Wisconsin, but it’s been hidden.

Josie Osborne: We have been erased from the history books.

Narrator: History is about more than a written record or important dates. It’s about people, about the actions they take, even those that go unseen, like finding one’s own courage or reaching personal liberation.

Josie Osborne: It’s so important that stories like this be told.

Narrator: Historians are now revealing a rich history of Wisconsin’s LGBTQ+ past. Telling stories of adversity, sacrifice, personal triumphs, and history-making moments

[starter gun fires]

Narrator: lost to time.

[cheers and applause]

Kai Pyle: There’s lots of different queer history, and it’s not all the same. It’s important to know about the past because it explains how we got where we are.

Dick Wagner: That’s part of the hidden history that needs to be unhidden.

[crickets chirping]

Kai Pyle: If you are living in North America, you’re living on indigenous land, and you need to know the history of the land you’re living on.

[wind brushes grass field]

The history of Two-Spirit people is an important part of that.

Narrator: Two-Spirit is a term used today for Native people, past and present, believed to possess both masculine and feminine spirit. It could be a person born male, but drawn to characteristically female roles throughout their life. Historically, Two-Spirit people were widely accepted by their communities and were known by many names.

Kai Pyle: We have a really rich vocabulary for describing gender and sexual diversity. In Anishinaabemowin, our language, it’s agokwe. For the Navajo, it’s nàdleehé. For Dakota people, it’s winkte. We have terms for people like us.

Narrator: Names differed by nation and language, as did a Two-Spirit person’s role in their society. But often, Two-Spirit people were highly respected and believed to possess special talents and insight.

Kai Pyle: It encompasses our world views, which are often very different from how Euro-American society defines gender and sexuality.

Narrator: Though embraced by their communities, Two-Spirit people were met with disdain by Western travelers. In 1830, American artist George Catlin traveled the Mississippi River and witnessed a Sauk and Meskwaki ceremony centered on a Two-Spirit member of the tribe. While the event may have been held in honor of the Two-Spirit, the title of Catlin’s painting reveals his attitude toward the subject.

Kai Pyle: The painting was called “The Dance of the Berdache.” The term ‘Berdache’ came to refer to what they would call, like, a passive homosexual, in their derogatory terms. Catlin describes it as one of the most disgusting and abhorrent facets of the New World; that it should be eradicated before it even can be recorded in any more detail.

[heartbeat]

§ §

Narrator: The Europeans who came to the New World brought very specific views about those who deviated from heterosexual norms. Eventually, those norms would be rigidly enforced.

Kai Pyle: Starting in the late 1800s, there was a big push to civilize Native people. The United States government and often also the religious organizations that ran many of the boarding schools were trying to make the kids into ‘cookie cutters’ of American boys and American girls.

Narrator: For Two-Spirit people, this was especially traumatic.

Kai Pyle: There are stories of Two-Spirit people who disappeared, essentially, from boarding schools. Once discovered to be Two-Spirit, they were taken away and never seen again.

[somber music]

Narrator: As Wisconsin became a territory in 1836, laws were created that called for harsh punishments for homosexual acts. The topic was widely considered taboo and kept out of conversation until 1895 when world events thrust it onto headlines across the globe.

[tense music]

Dick Wagner: London was the world’s capital. Wisconsin newspapers would have a column from London talking about the arts and political happenings. Oscar Wilde was the toast of the town.

Narrator: Playwright Oscar Wilde was one of the first global celebrities. He had even visited Wisconsin on a speaking tour. But in London in 1895, he was put on trial, and his homosexuality was exposed in salacious detail.

Dick Wagner: The coverage reveals a total negative perception about homosexuality. “Wilde’s Disgrace” and “Shame for Oscar.” One paper ran with the headline, “Wilde Not Yet a Suicide,” as if he should certainly be one.

[ship blows horn, ship engine hums]

Narrator: In La Crosse, Wisconsin, the city’s many newspapers ran updates on Wilde’s trial in 1895. That year, George Coleman Poage was coming of age and entering La Crosse High School.

[waltz music]

Ashley Brown: Poage was a very intelligent young man. We know that he was a voracious reader. It’s not out of the realm of possibility that he was reading about the trial of Oscar Wilde, gaining a very clear sense of what America and, indeed, what the world thought about gay men.

Narrator: Poage’s story reveals the challenges of telling LGBTQ+ history from a time when true identity had to be a closely guarded secret, one Poage would carry his entire life.

Ashley Brown: Homosexuality very often has been something that society has viewed as shameful. And there can be a tremendous silence.

Narrator: Poage graduated from La Crosse High School as salutatorian, then went on to the University of Wisconsin to study history. He would make history himself by stepping onto the track.

Ashley Brown: When he joins the track team, lo and behold, he is the first African American on the track team at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Official: On your marks, set!

[fires starter gun]

[cheering]

Narrator: Poage excelled at the hurdles, a standout, earning himself an invitation to compete at the 1904 Olympics. § Meet me in St. Louis, Louis

§ §

Meet me at the fair §

Narrator: The 1904 Olympic Games were held as a part of the World’s Fair in St. Louis, a notoriously segregated city. Even as a competitor on the world stage, Poage was isolated from his fellow athletes when not competing.

Ashley Brown: He would have been with them, but not regarded quite as the same. He spent the vast majority of his life living in that kind of America.

§ §

Narrator: Segregated, alienated, Poage would not waver.

[fires starter gun]

In St. Louis, history was waiting for him at the finish line.

Ashley Brown: He won two bronze medals, making him the first African American to win medals at the Olympic Games.

Narrator: George Coleman Poage from La Crosse, Wisconsin, was among the world’s best. A triumph and a moment for American history. However, in the subsequent decades, Poage’s achievements would be nearly forgotten. That would start to change when UW-La Crosse historian Bruce Mouser helped revive interest in the athlete.

Audrey Mouser Elegbede: From my dad’s perspective, Poage’s story was one that just hadn’t received the recognition that it deserved. It seemed to have been forgotten by history. Just not… documented.

Narrator: As Bruce Mouser started to document Poage’s post-Olympic life, certain clues began to emerge, pointing to a hidden aspect of Poage’s story. He resigned a St. Louis teaching position under a cloud of suspicion. He moved to Chicago’s gay-friendly Cabaret District.

Ashley Brown: Poage also joined the Chicago Athletic Club, considered a social outlet for gay men.

Audrey Mouser Elegbede: Poage had to keep quiet or downplay many of the things that made him who he was.

Narrator: Bruce Mouser had clues that supported a theory that Poage had been a gay man. But he didn’t feel that he had enough evidence to make this claim.

Audrey Mouser Elegbede: To out someone after their passing has considerable impact, and I think he wanted to be respectful not only of Poage, but with the family. Is that part of his identity they wanted to share?

Jennifer Livingston: It’s been years in the making, but today Poage Park officially had its grand opening ceremony.

Narrator: Mouser’s research had helped ignite interest in the community about their historic Olympian. Poage’s relatives came to La Crosse for the park dedication. Mouser was unprepared for what happened when meeting Poage’s grand-nephew.

Audrey Elegbede: The nephew really, in sort of a casual way, sort of,

[speaking softly]

“You know my uncle was gay.” It made it possible for him to complete Poage’s story.

Ashley Brown: It’s really about giving a full account of the individual’s life. A person’s sexuality also matters in the sense that this is a part of their identity.

Audrey Mouser Elegbede: It was uncovering… uncovering a life.

Narrator: Over 100 years after making Olympic history, George Coleman Poage was welcomed home.

Audrey Mouser Elegbede: For there to be acknowledgment for who Poage was, both as an athlete and as a man–

[piano chords]

Narrator: For a man like Poage, the early 20th century’s social and legal limitations on sexual expression forced him into a hidden life. Across the state in Milwaukee, another man of the time, Ralph Kerwineo, was hiding in plain sight.

Kai Pyle: Ralph Kerwineo was a Black and Native man who was extremely stylish. If you look at his photos, he’s got it going on…

[chuckles]

for sure!

Narrator: Kerwineo’s style would fly in the face of the era’s strict policing of gender expression.

Kai: Ralph became briefly infamous in Milwaukee in 1914. He was arrested by the police for allegedly passing as a man and marrying two women. He was known as the ‘Girl-Man of Milwaukee.’

Narrator: Born in Kendallville, Indiana, and raised as Cora Anderson, Kerwineo hoped for a career in one of the few fields available to women. In 1900, while in nursing school in Chicago, Kerwineo met Mamie White, and the two started out life together. However, both struggled to find work at a time when immoral doctors could take advantage, demanding sexual favors before hiring. With few opportunities, the two young nurses calculated a man’s wage would make their life together much better.

Kai Pyle: They decided to move to Milwaukee, and this person started to live as the person known as Ralph Kerwineo.

Narrator: Kerwineo found work as a bellboy at the Plankinton Hotel. Then, as a factory hand. White kept care of their home. They appeared to all as a traditional husband and wife. Then, as happens in many relationships, troubles began.

Kai Pyle: Ralph, in Mamie’s eyes, started to get too… comfortable with his expression as a man. Coarse in his habits, going out with other men after work. Eventually, they split. And a little while later, Mamie discovered that Ralph was seeing Dorothy Kleinowski and that they were, in fact, getting married.

Narrator: Hurt and angry at Kerwineo, White showed up at his workplace under the guise of applying for a job. Told they had no work suited for women, White revealed they already had a female employee and uncovered Kerwineo’s secret.

Kai Pyle: This blew up all over the papers.

Narrator: Kerwineo was arrested. In 1914, it was against the law to wear the clothes of another gender.

Kai Pyle: I can’t imagine being incarcerated and then paraded through newspapers, having your name dragged all over the place.

Narrator: The name being dragged was Cora Anderson, the identity Kerwineo had long left behind. His effort to live honestly as he saw himself would be called dishonest and deceptive.

Kai Pyle: It’s a story that tells us a lot about the way gender-variant people have been criminalized in the past.

Narrator: Kerwineo was forced into a dress as part of a sensational public trial.

[judge banging gavel]

The overflowed crowd laughed when, under oath, he had no choice but to say he was a woman.

Kai Pyle: He was released as long as he promised that he “would return to wearing skirts,” as they put it.

Narrator: At the end of the trial, Kerwineo was quoted: “When we leave this court, Kerwineo will be dead. My name when I leave here will be Cora Anderson.”

[dramatic orchestra]

But Ralph Kerwineo would not die.

Kai Pyle: After his arrest, he went around with some vaudeville circuits. He would start off the show dressed as a woman, then show up as a man, vice versa.

Narrator: And he kept presenting as male for long after the infamous trial.

Kai Pyle: I think it shows a lot of resilience on Ralph’s part. It was 1914, and we can’t necessarily apply labels from today to somebody who lived a hundred years ago. But he said his woman’s soul had died, and a man’s soul had taken its place. Ralph was going to do whatever Ralph wanted. Whoever he was, he had a strong spirit and free will.

Narrator: Despite his strong spirit and free will, mainstream America was not ready for Ralph Kerwineo to live his full life freely among them. Society had rejected him. In this same era, another Wisconsin man found his solution to living freely by building his own personal oasis, removed from society and even time.

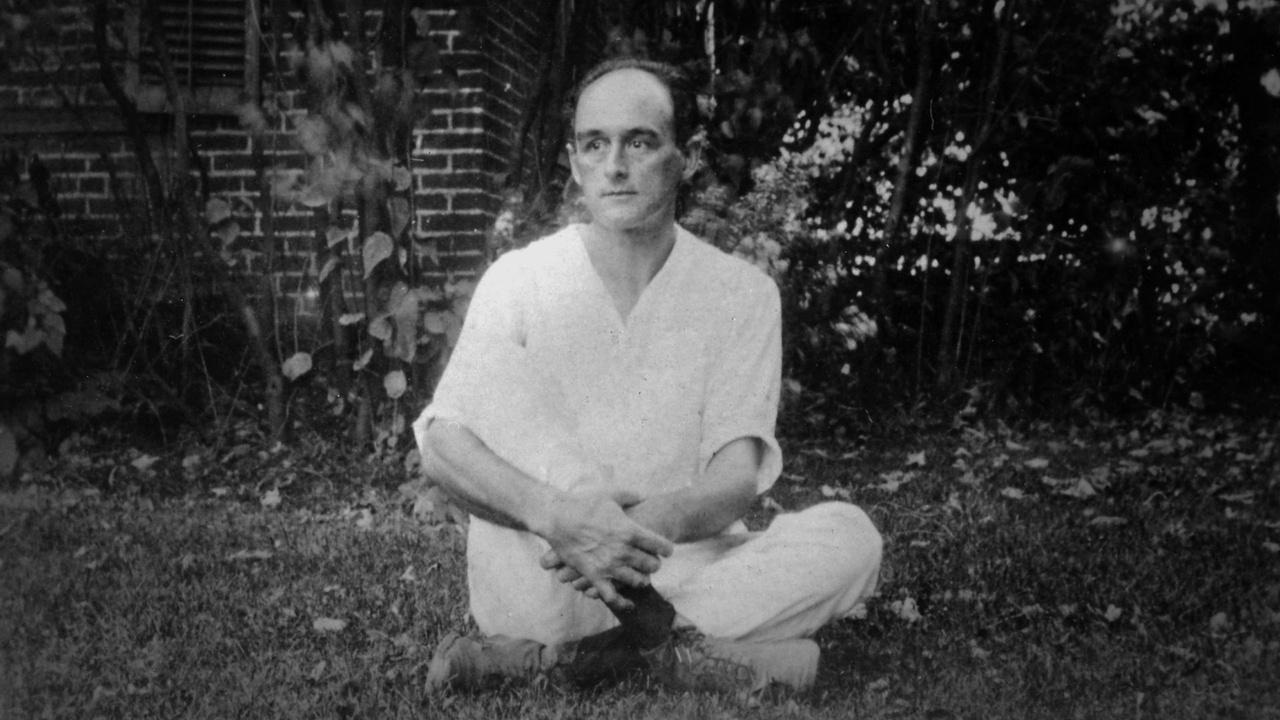

Dick Wagner: Ralph Warner of Cooksville, I call Wisconsin’s first out gay man.

[acoustic guitar]

Narrator: An eccentric, living a lifestyle from a century before his time, Ralph Warner entertained guests at his home and personal preservation project, which he named ‘The House Next Door.’ The old building on a small plot in rural Wisconsin was Warner’s very own gateway, transporting him from the 1920s back to the mid-1800s.

Larry Reed: He was an unusual character and doing an unusual thing, sort of liking old stuff. People were tossing that stuff away.

Narrator: Warner’s interests ran counter to the mood of his times, as 1920s America became more urban and less rural. His deliberate effort to slow the increasingly frenetic pace of life caught the attention of magazines and newspapers.

Larry Reed: The word was out. Good Housekeeping, House and Garden. Ralph Warner put Cooksville on the map.

Narrator: Warner’s land of long ago promised more than a collection of antiques and old-fashioned meals. It was a place where one could live a different life.

Will Fellows: Warner was really, in some ways, ministering to certain people who were looking for something to soothe their angst about the ways in which American life was changing.

[engine rumbles]

But then, ironically, the automobile, which in some ways was the bane of preservation, was also the lifeline that brought people to Cooksville to find their hours of respite in Warner’s creation of The House Next Door.

Larry Reed: Ralph Warner’s House Next Door was charming, just a charming little place. People called it “a wee bit of England in Wisconsin.”

Will Fellows: Summer evenings with the windows open, the sound of song and piano from the House Next Door traveling through this little village.

Narrator: But the main attraction was Ralph Warner himself.

Dick Wagner: He tells one lady who comes to look at his curios: “Well, you should look at me. I’m the most curious thing here.” So, he had just sort of created this persona for himself. And they gave fairly good clues about who he was.

Narrator: Warner defied the strict gender norms of the 1920s. He entertained his visitors by cooking and serving the meals himself. He designed and curated the interior of his home, and tended his traditional English garden.

Will Fellows: It’s representative of a certain strain of the gay sensibility. It includes that love of things related to the home and decor, things related to hospitality and caregiving.

Dick Wagner: By presenting himself as who he was, he was, in his own way, for his own time, coming out, which is really quite remarkable for the 1920s.

Narrator: Through the House Next Door, Warner had created his own personal haven. A place removed from time, where people could be who they wanted to be.

Will Fellows: He really viewed it as a sacred little space that he would share with people, like-minded, kindred spirit type people.

Narrator: Ralph Warner’s the ‘House Next Door’ was a predecessor to the coming heritage tourism movement in Wisconsin. The next generation to undertake historical preservation often looked to Warner as an inspiration. Such was the case for Edgar Hellum, who still remembered Warner well when interviewed in his nineties.

Edgar Hellum: Mr. Warner, Ralph Warner, had an old house that he had restored, and he served meals. That’s what gave me the bug.

§ §

Narrator: In 1934, Hellum met Bob Neal. Through a shared passion for old buildings, a life partnership would develop. In a letter sent right after their meeting, Hellum gushed, “Bob Neal, just the name makes the weekend seem like make-believe!” The two men lived at a time when they needed to keep their love for each other a secret. However, the life’s work they built together would draw attention and admiration for generations.

[elegant piano]

In the early 1800s, prospectors swarmed Southwestern Wisconsin in search of lead ore. They dug caves into the hillsides, reminiscent of badger holes, earning the namesake the ‘Wisconsin Badgers.’ In the 1830s, Cornish immigrant miners settled in the boomtown of Mineral Point, building tiny stone cottages for their family homes.

Will Fellows: These were very small, modest dwellings, some of which seemed to almost grow out of the bluff behind them.

Narrator: By the mid-1930s, the cottages had been long abandoned. They were being torn down for their materials. But where others saw ruin, Edgar Hellum and Bob Neal saw beauty.

Edgar Hellum: Bob said, “I’ve found a house,” but he said, “It’s so decrepit.” He said, “I don’t know whether it can be fixed or not. Can you come over and take a look?” And he had found Pendarvis House. Oh, God, it was awful!

[chuckles heartily]

Narrator: So, for ten dollars and a dream, the two men purchased the cottage and set about restoring it.

Will Fellows: People thought they were kind of nuts. These two young men down on the slummiest street in town living together in one of these rundown stone cottages a lot of people thought should just be knocked down.

Dick Wagner: It was an unusual thing to happen in a small Wisconsin town. They were often described as artistic young men, and it probably was true in that you had to have some sense of what could be, which is what artists do is they create something out of almost nothing.

Narrator: After many months of working sixteen-hour days, Hellum and Neal had restored the home to its 1800s aesthetic. They gave it the Cornish surname ‘Pendarvis.’

Will Fellows: Bob and Edgar were thrilled but needed to make some sort of a living from it.

Narrator: They started with opening a small tea room at Pendarvis. But it soon evolved into a quaint restaurant, embracing the historic identity of the locale. For their signature dish, Bob Neal turned to his family’s old Cornish recipes and landed on the pasty.

Will Fellows: Even though the food itself was very basic, almost kind of like a peasant food in a way, there was a touch of finesse to the meal.

Edgar Hellum: We made the best pasty that anybody made in Mineral Point. We used top-grade beef. We had a good crust recipe, and then, it had to come right from the oven to the table. Simple farm fare, but we did it with a touch of class.

Will Fellows: The focus was not fine dining. The focus was the experience.

Narrator: A pasty was served with a flourish for the table to share while Bob Neal told tales of the Cornish miners who had settled old Mineral Point.

Dick Wagner: Bob Neal clearly had a vision for what heritage tourism could be.

Narrator: By the late 1940s, Pendarvis House restaurant had become a niche destination. The tiny operation received national visibility after being included in an influential travel guide written by food critic and later cake-box celebrity Duncan Hines.

Edgar Hellum: Duncan Hines, he said, “Don’t change a thing, don’t change a thing.”

[laughs warmly]

Narrator: Over the next several decades, Neal and Hellum acquired additional stone cottages in Mineral Point. A restoration project that became their life’s work, and one of Wisconsin’s most-visited historic sites.

Dick Wagner: Pendarvis really sparked and grew historic tourism here in Wisconsin.

Will Fellows: Gay men made an extraordinary contribution in preservation. Both Warner and Bob Neal and Edgar Hellum, they were really early advocates for cultural tourism.

Narrator: The two men complemented each other. Neal handled the food and championed Cornish lore, while Hellum brought the old buildings back to life. Though it was an age when they needed to keep their love for each other a secret, their shared vision and artistic endeavor endures to this day.

Dick Wagner: It’s a remarkable story of how two gay men led their lives to create this artistic and historic place. It’s not just part of the Cornish lore, but it’s part of the gay history of the state.

While Pendarvis was a passion to preserve, another couple was embracing change, exploring a new and radical art movement through their school in Milwaukee.

Josie Osborne: The Layton School of Art was started by two women in 1920, Miss Partridge and Miss Frink.

Narrator: Charlotte Partridge and Miriam Frink met at Downer College for Women in Milwaukee in 1915. Historically, women’s colleges were a place where romantic female relationships could safely thrive. For Partridge and Frink, their love and commitment for each other thrived for more than 50 years.

Josie Osborne: Charlotte Partridge was charismatic. She was just sort of lovable, right? She smiled a lot. She was the gregarious one. Miriam Frink, she was much more serious and let Charlotte be the front person.

Narrator: The two made friends with Milwaukee businessman Frederick Layton, the meatpacking millionaire who had opened the Layton Gallery in 1888, and filled it with grand works purchased on his travels. In 1920, Layton offered the gallery basement to Partridge and Frink to hold classes. But the art they would inspire would be radically different from the old works that filled the gallery’s walls.

Josie Osborne: Charlotte Partridge and Miriam Frink were more aligned with what was happening in terms of the European avant-garde.

Narrator: European avant-garde movements like Cubism and Dadaism challenged artistic conventions, shocked some, and spoke deeply to others.

Josie Osborne: For Charlotte Partridge and Miriam Frink, they brought these avant-garde ideas into their teaching, into their own art collection in their home, and embraced it.

[piano]

Narrator: In the house the couple had designed and built together, they hung modern works of art at home among bold creative expressions.

Josie Osborne: There’s a pretty strong connection between queer identity and avant-garde movements. There’s something about growing up knowing you’re different from what the rest of society says people should be, just makes you more open to new ideas.

Narrator: New ideas fueled Partridge and Frink’s avant-garde art school.

Josie Osborne: The Layton School of Art was basically an incubator for creative expression.

Narrator: Like Europe’s Bauhaus, the Layton School put art and design on equal footing. Nude drawing classes were attended by students of both sexes, something previously unheard of in Milwaukee. Generations of graduates would contribute to the city’s art scene and design of its products.

Josie Osborne: They’re developing these creative minds, really sent a lot of people out into the community with this training and this understanding of what was possible.

Narrator: All things seemed possible for the Layton School. Through the Great Depression, the two leaders took no salary to stay open. During World War II, they held free art shows intended to build public support for the war effort. After the war, enrollment boomed. Partridge and Frink would greet the 1950s with a bold plan for a new modern home for the school. But times were changing.

Josie Osborne: The 1950s were not, not a good time to be a woman. Definitely not a good time to be a queer woman. They had just raised all the money to build this amazing building. Then it was determined that it wasn’t appropriate for two women to be leading a school of national reputation.

Narrator: The Layton School’s male-dominated board forced Charlotte Partridge and Miriam Frink to leave the school they founded and nurtured for decades. Their last work was scratching a pencil edit to the board’s resolution, making it crystal clear that their retirement was not voluntary. Without their leadership, the Layton School ultimately struggled. Its sleek headquarters were condemned for a highway project in the late ’60s. A few short years later, the Layton School closed. The doors shut on a life’s endeavor. The couple remained involved in Milwaukee’s community, with Partridge leading efforts in building senior housing. Their impact on the city’s art scene would live on. In 1974, a group of former Layton School instructors started the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design (MIAD). MIAD continues today as a world-class art and design school, training students in understanding what’s possible. A legacy sparked by Charlotte Partridge and Miriam Frink.

Josie: I discovered what bad–

[whispers]

Can I say ‘badass?’

[laughs]

I discovered what total badasses they were! These stories are beginning to emerge that gay and lesbian people are making a huge difference in our culture. They’re people who blazed a trail for me to be able to be who I am. But they’re also people who did great things.

Narrator: Throughout the early 20th century, the LGBTQ+ community made significant, yet unsung contributions to Wisconsin history. They were also there to contribute, to step up when world history turned dark. As Nazi Germany swept across Europe, Americans joined the fight for the free world, including gay men, hoping their commitment to the war effort would lead to greater inclusion back home. But gay soldiers would have to serve in silence.

Dick Wagner: Gay men were fighting in the service, even though the service didn’t want them. Unwanted yet undeterred, gay men answered the call.

Dick Wagner: They not only had to fight the homophobia of the military system, but then, they had to fight fascism, too.

Narrator: Motivated by the prospect of a freer society after the war, this was especially true for a young soldier from Rhinelander, Wally Jordan.

Dick Wagner: During the war, Wally Jordan was having gay pen pals that he was keeping a correspondence with.

Narrator: Jordan’s letters provided personal insight into gay men who communicated frankly, despite the risk of discovery, sharing their thoughts on the war, hopes for the future.

Dick Wagner: He writes in these letters that he has a vision that after the war, there will be a big national conference of gay men, where they will proudly proclaim their rights and demand that they be respected. After World War II, there could be a better world, and that better world ought to encompass the gay men who had been fighting to win the war for the Allies.

Narrator: But a hero’s welcome would not be waiting, even for those who put it all on the line.

[propellers rotating]

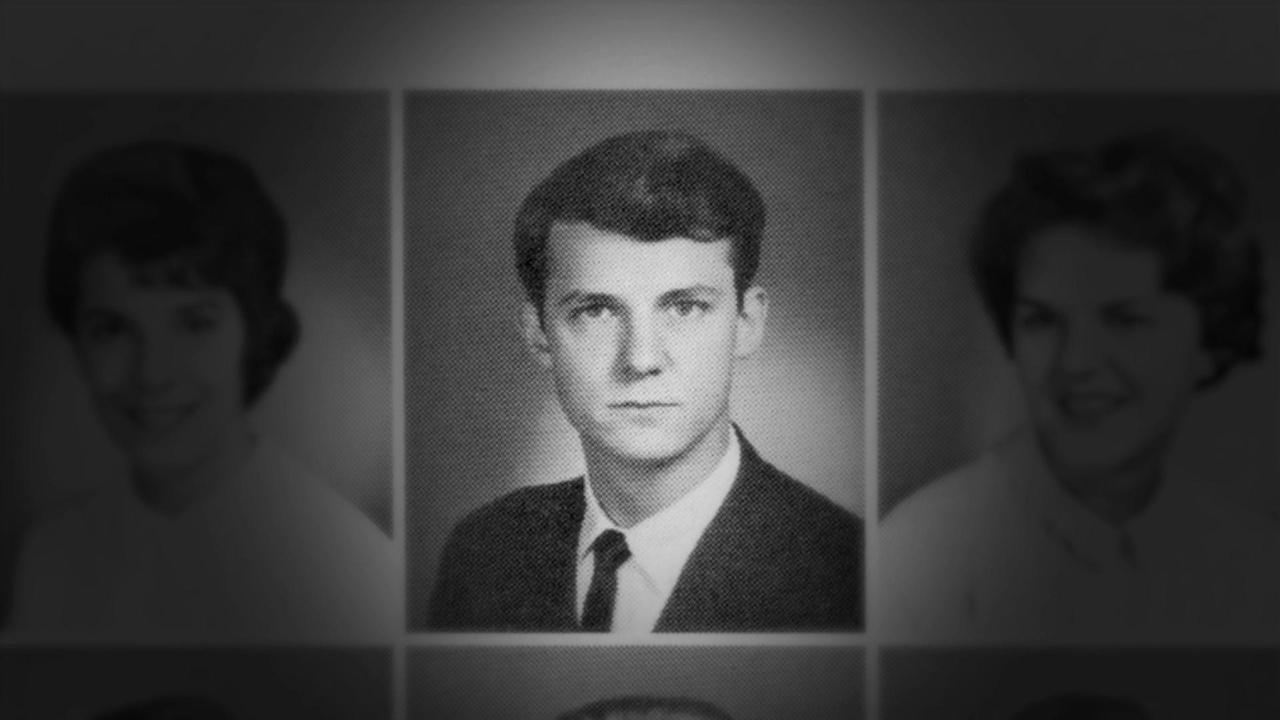

Lieutenant Kenneth Palmer from Edgerton, Wisconsin, was a decorated war hero, surviving over 50 dangerous missions, including a harrowing bombing run over Munich. As he navigated his B-24 bomber over his target, the plane took on heavy anti-aircraft fire. A piece of flak ripped through the nose of his plane, sending shrapnel flying toward Palmer. His jacket took the brunt, shredding into pieces. But the young navigator miraculously walked away with little more than a few bruises and a story for the ages. He quipped, “If they can come that close and not get me, I’m safe.”

[bell ringing]

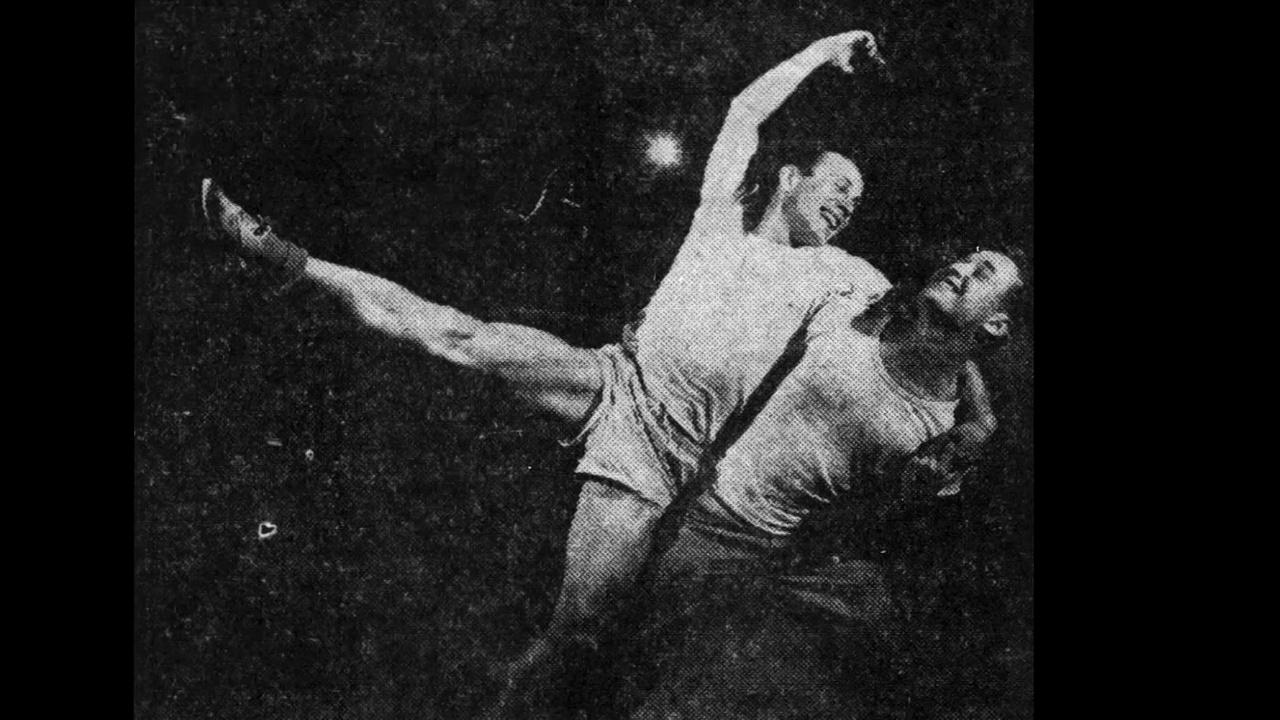

After the war, Kenneth Palmer returned to college at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He and so many of his fellow veterans were looking to catch up on the years and opportunities lost to the war. Palmer studied commerce and served as secretary and also performer in the extracurricular theater troupe, the Haresfoot Club.

[applause]

[band plays rousing music]

Scott Seyforth: Haresfoot was a theatrical organization that formed on campus in the late 1890s.

Singers: Have you ever been to a picture show? No!

Scott Seyforth: And they were very popular at the time. They would perform six, seven, eight sold-out shows. And they would get on the train, and they would do a tour. They thought it was good publicity for the University, but they didn’t like the idea of sending men and women out together on the road. It turned into one of these all-male companies where men played the women’s roles.

Haresfoot Cast: Follow the girls

§ §

[inaudible]

§ §

Follow the girls

Narrator: The Haresfoot motto became “All our girls are men, yet everyone’s a lady.”

Scott Seyforth: They’d go to Eau Claire and La Crosse, sometimes to St. Paul, and do their shows.

[men singing]

It was the Wisconsin Idea in drag.

[applause]

Dick Wagner: Though the company was predominantly heterosexual, there were a lot of gay men who were attracted to Haresfoot.

Narrator: The theater was a sanctuary.

Dick Wagner: You have both sexuality and gender identity all mixed up together.

The element of drag allowed performers to experiment with gender roles publicly. To be expressive about sexuality under the protection of theatrical satire.

Dick Wagner: Haresfoot was willing to push those boundaries.

Narrator: In 1948, the Haresfoot Club was celebrating its 50th anniversary with an original show, Big as Life, a send-up of the legendary Paul Bunyan myth. The cast included senior Kenneth Palmer, donning a red wig to portray the female role of Mabel. The group’s 50th year would be a fateful one.

Scott Seyforth: A University police officer found two men making out in a car on campus, and he arrested them. In their car was an invitation to a party at a private home.

Narrator: Police raided the Adams Street house party and made arrests on morals and sodomy charges.

Scott Seyforth: Two of the men involved in that sting operation were members of Haresfoot.

Narrator: Kenneth Palmer was arrested, his name and address printed in the newspaper. The press called the home “a den for lewd activities.”

Dick Wagner: On campus, there was concern about this growing outbreak of homosexuality. And so, there was an investigation launched of the Haresfoot theater troupe.

Narrator: The investigative committee called upon psychiatrist Dr. Annette Washburne for guidance.

Scott Seyforth: Dr. Washburne had a classification of homosexuals. She believed that there were ‘pseudo homosexuals’ that could be treated. ‘True homosexuals’ were a danger on campus, and she really believed that the University needed to get rid of those people.

Narrator: Kenneth Palmer completed his requirements for graduation. But at the highest levels of the University, his degree was denied.

Scott Seyforth: There’s a belief that to graduate gay men into society is a stain on the University. It’s appalling. It’s regrettable. It’s unfathomable.

In 1950, Cold War tensions were brewing in Korea. War hero Kenneth Palmer anticipated a return to service. He pleaded with the University to have his degree granted, emphasizing that it would be unlikely for him to rise through the officer ranks without a diploma. Once again, he was denied.

Narrator: Fallout from the Haresfoot Scandal would not end with Palmer. A silent force would push the next generation of gay students deeper into hiding.

Lewis Bosworth: I was at home in my apartment one day in 1962, and the phone rang.

[rotary phone rings]

It was one of my friends. He explained to me that there was this purge going on to rid the University of gay male students.

Scott Seyforth: Lewis Bosworth, he is one of only two former students that has ever spoken publicly about their involvement in the purge.

Narrator: The purge was a systematic effort to identify gay students and staff and discretely remove them from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The policy was a carryover from the paranoia of the 1950s, starting with the Red Scare.

Joseph McCarthy: Even if there were only one communist in the State Department, that would still be one communist too many.

Narrator: Which led to the Lavender Scare, a campaign to ban homosexuals from working in the federal government.

Ashley Brown: Gays and lesbians really became the scapegoats. It is assumed that gay men and lesbians are actually threats to national security and that they can be blackmailed.

The hunt for homosexuals at the University began as a response to the Haresfoot scandal. Fourteen years later, in 1962, the purge pressed on.

Dick Wagner: The Dean of men, Dean Zillman, started to compile a list of hundreds of male homosexuals on campus. And he would call people in and ask them to name names, which was clearly a McCarthy-type tactic.

Narrator: Theodore Zillman had been an attorney and personally questioned suspected homosexuals. Heavy consequences awaited those who confessed.

Dick Wagner: The University would inform parents, basically, would force the kids to come out.

Scott Seyforth: They were ruining people’s lives. Kicking out people right before graduation. There are cases of students attempting suicide. You read these transcripts. It’s heartbreaking.

Narrator: One name on Zillman’s list was sophomore Lewis Bosworth.

Lewis Bosworth: I was getting calls from the Dean’s office to come in, and I ignored it as long as I could, simply on the grounds that it wasn’t any of their business.

Scott Seyforth: Dean Zillman didn’t like it when people didn’t respond to his request.

Lewis Bosworth: A detective from the University Police came to my place of employment and threatened me. And so, I finally did go to the Dean of Men’s office. They certainly were a whole lot worried about gay men, young men.

Scott Seyforth: Dean Zillman interrogated him. It must have been terrifying to be on the receiving end of an interrogation about your sexuality in the 1960s.

Lewis Bosworth: I was afraid that I might be expelled. Well, I lied through my teeth when he asked me if I was homosexual. Since I denied everything, there wasn’t anything they could do with me.

Narrator: But Dean Zillman had other plans.

Lewis Bosworth: I had been accepted to a program abroad, a junior year abroad program. Well, they reneged on that. They took away the scholarship. I graduated in ’64. There were other people involved in that who fared less well than I did.

Narrator: Hunted, harassed, the University’s years-long purge ensured that hundreds of gay students would never make it to graduation.

Lewis Bosworth: It was important to their quote-unquote investigation to get as many names on their list as they could, and I refused to do that. I didn’t give them any names.

Narrator: Defiant in the face of bigotry, Lewis Bosworth went on to become an outspoken activist. He later returned to UW-Madison and built a career centered on welcoming students, helping them navigate the college experience rather than kicking them out.

[birds chirping]

Scott Seyforth: It was spring of 2013. I went into the LGBTQ+ graduation ceremony. And sitting at one of the tables was Lewis Bosworth, sitting by himself. I was stunned. I said, “Lewis, what is it like for you to be at this?” He says, “Scott, it’s unimaginable. “When I was this age, this would have been unimaginable.”

Dick Wagner: One of the amazing things about Wisconsin is that early on, gay and lesbian people found ways to affirm their own identity. In their own way, they could achieve a certain amount of liberation.

Kai Pyle: You can learn to understand people if you know their history.

Narrator: A history often hidden. But history would soon be made out in the open.

Ashley Brown: Well, the battles never end. There are forces really that come together that try to turn the tide.

Narrator: A movement to be part of the American story. To no longer live a hidden life.

Dick Wagner: People were liberating themselves, knowing that their lives were something that they had to live and were valid to live.

Announcer: Funding for Wisconsin Pride is provided by Park Bank, S.C. Johnson, Greater Milwaukee Foundation, Evjue Foundation, the charitable arm of the Capital Times, CUNA Mutual Group, New Harvest Foundation, West Foundation, Paula Bonner and Ann Schaffer, La Crosse Community Foundation, MG&E Foundation, Rogers Behavioral Health, with additional support from and with support from Focus Fund for Wisconsin Programs, and Friends of PBS Wisconsin.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us