Wisconsin Pride – George Poage

§ §

Narrator: As Wisconsin became a territory in 1836, laws were created that called for harsh punishments for homosexual acts. The topic was widely considered taboo and kept out of conversation until 1895 when world events thrust it onto headlines across the globe.

[tense music]

Dick Wagner: London was the world’s capital. Wisconsin newspapers would have a column from London talking about the arts and political happenings. Oscar Wilde was the toast of the town.

Narrator: Playwright Oscar Wilde was one of the first global celebrities. He had even visited Wisconsin on a speaking tour. But in London in 1895, he was put on trial, and his homosexuality was exposed in salacious detail.

Dick Wagner: The coverage reveals a total negative perception about homosexuality. “Wilde’s Disgrace” and “Shame for Oscar.” One paper ran with the headline, “Wilde Not Yet a Suicide,” as if he should certainly be one.

[ship blows horn, ship engine hums]

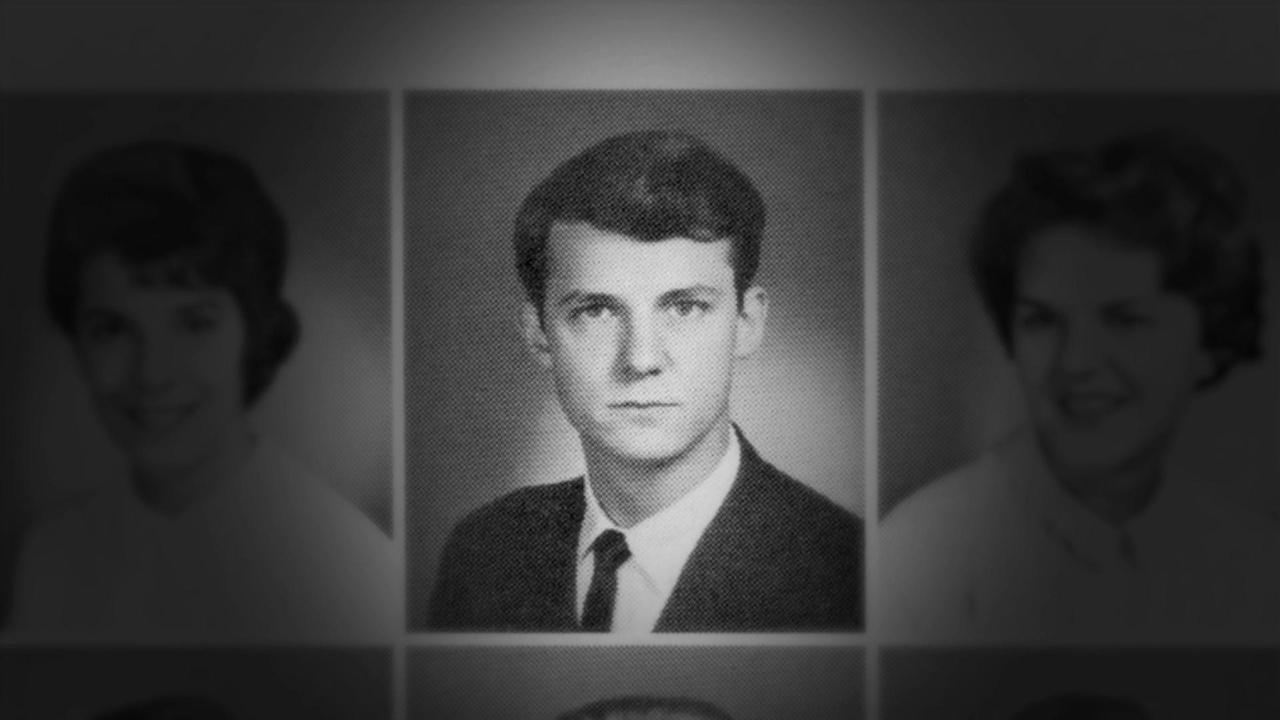

Narrator: In La Crosse, Wisconsin, the city’s many newspapers ran updates on Wilde’s trial in 1895. That year, George Coleman Poage was coming of age and entering La Crosse High School.

[waltz music]

Ashley Brown: Poage was a very intelligent young man. We know that he was a voracious reader. It’s not out of the realm of possibility that he was reading about the trial of Oscar Wilde, gaining a very clear sense of what America and, indeed, what the world thought about gay men.

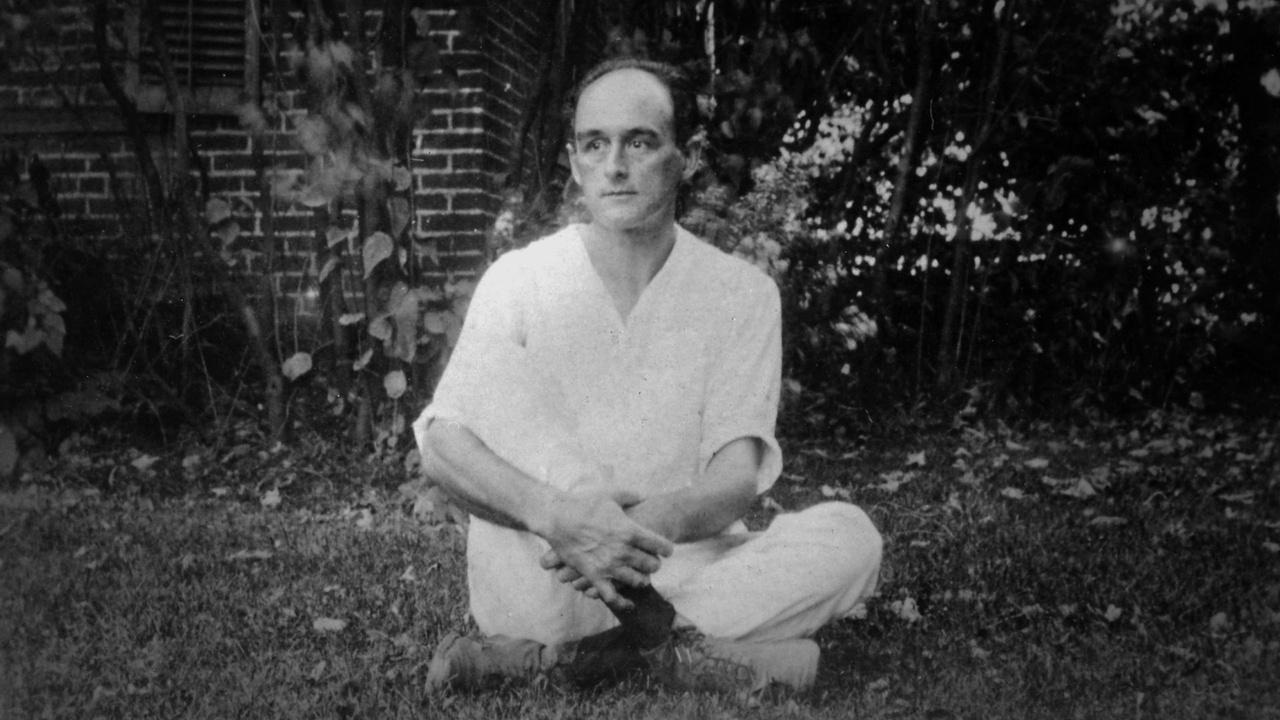

Narrator: Poage’s story reveals the challenges of telling LGBTQ+ history from a time when true identity had to be a closely guarded secret, one Poage would carry his entire life.

Ashley Brown: Homosexuality very often has been something that society has viewed as shameful. And there can be a tremendous silence.

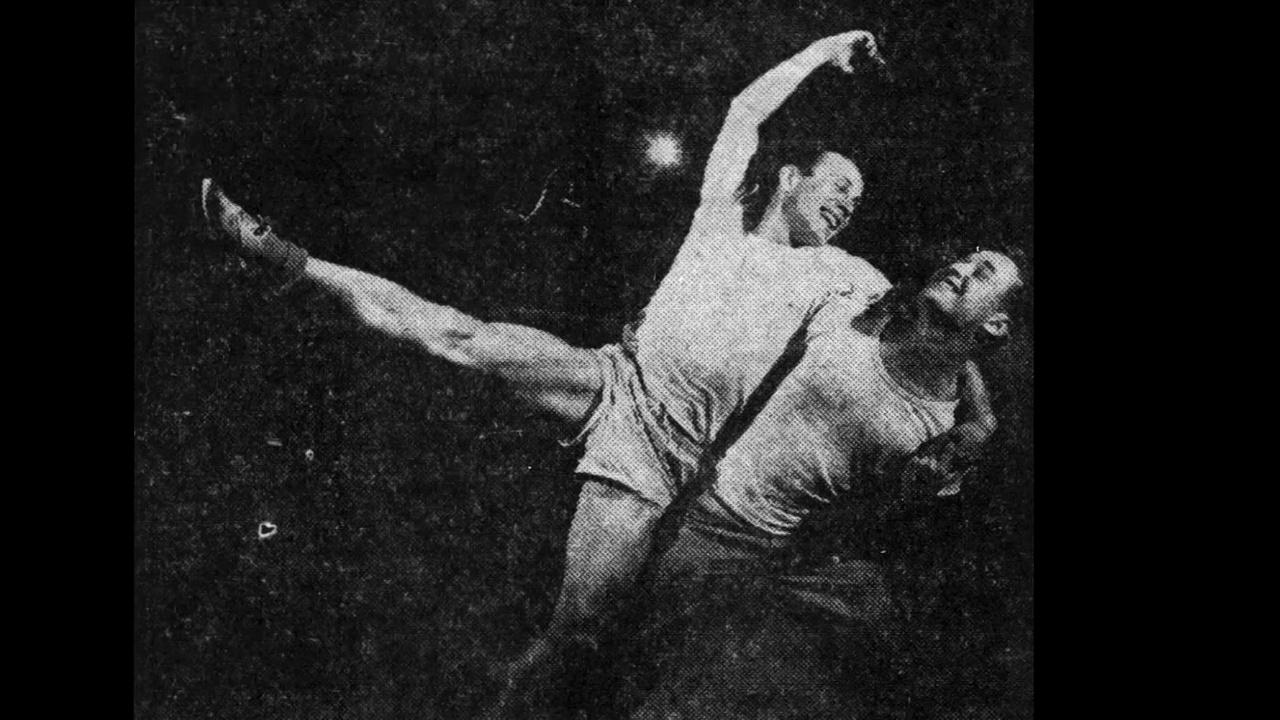

Narrator: Poage graduated from La Crosse High School as salutatorian, then went on to the University of Wisconsin to study history. He would make history himself by stepping onto the track.

Ashley Brown: When he joins the track team, lo and behold, he is the first African American on the track team at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Official: On your marks, set!

[fires starter gun]

[cheering]

Narrator: Poage excelled at the hurdles, a standout, earning himself an invitation to compete at the 1904 Olympics. § Meet me in St. Louis, Louis

§ §

Meet me at the fair §

Narrator: The 1904 Olympic Games were held as a part of the World’s Fair in St. Louis, a notoriously segregated city. Even as a competitor on the world stage, Poage was isolated from his fellow athletes when not competing.

Ashley Brown: He would have been with them, but not regarded quite as the same. He spent the vast majority of his life living in that kind of America.

§ §

Narrator: Segregated, alienated, Poage would not waver.

[fires starter gun]

In St. Louis, history was waiting for him at the finish line.

Ashley Brown: He won two bronze medals, making him the first African American to win medals at the Olympic Games.

Narrator: George Coleman Poage from La Crosse, Wisconsin, was among the world’s best. A triumph and a moment for American history. However, in the subsequent decades, Poage’s achievements would be nearly forgotten. That would start to change when UW-La Crosse historian Bruce Mouser helped revive interest in the athlete.

Audrey Mouser Elegbede: From my dad’s perspective, Poage’s story was one that just hadn’t received the recognition that it deserved. It seemed to have been forgotten by history. Just not… documented.

Narrator: As Bruce Mouser started to document Poage’s post-Olympic life, certain clues began to emerge, pointing to a hidden aspect of Poage’s story. He resigned a St. Louis teaching position under a cloud of suspicion. He moved to Chicago’s gay-friendly Cabaret District.

Ashley Brown: Poage also joined the Chicago Athletic Club, considered a social outlet for gay men.

Audrey Mouser Elegbede: Poage had to keep quiet or downplay many of the things that made him who he was.

Narrator: Bruce Mouser had clues that supported a theory that Poage had been a gay man. But he didn’t feel that he had enough evidence to make this claim.

Narrator: Bruce Mouser had clues that supported a theory that Poage had been a gay man. But he didn’t feel that he had enough evidence to make this claim.

Audrey Mouser Elegbede: To out someone after their passing has considerable impact, and I think he wanted to be respectful not only of Poage, but with the family. Is that part of his identity they wanted to share?

Jennifer Livingston: It’s been years in the making, but today Poage Park officially had its grand opening ceremony.

Narrator: Mouser’s research had helped ignite interest in the community about their historic Olympian. Poage’s relatives came to La Crosse for the park dedication. Mouser was unprepared for what happened when meeting Poage’s grand-nephew.

Audrey Elegbede: The nephew really, in sort of a casual way, sort of,

[speaking softly]

“You know my uncle was gay.” It made it possible for him to complete Poage’s story.

Ashley Brown: It’s really about giving a full account of the individual’s life. A person’s sexuality also matters in the sense that this is a part of their identity.

Audrey Mouser Elegbede: It was uncovering… uncovering a life.

Narrator: Over 100 years after making Olympic history, George Coleman Poage was welcomed home.

Audrey Mouser Elegbede: For there to be acknowledgment for who Poage was, both as an athlete and as a man.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us