Wisconsin Pride – Pendarvis

§ §

Narrator: Ralph Warner’s the ‘House Next Door’ was a predecessor to the coming heritage tourism movement in Wisconsin. The next generation to undertake historical preservation often looked to Warner as an inspiration. Such was the case for Edgar Hellum, who still remembered Warner well when interviewed in his nineties.

Edgar Hellum: Mr. Warner, Ralph Warner, had an old house that he had restored, and he served meals. That’s what gave me the bug.

§ §

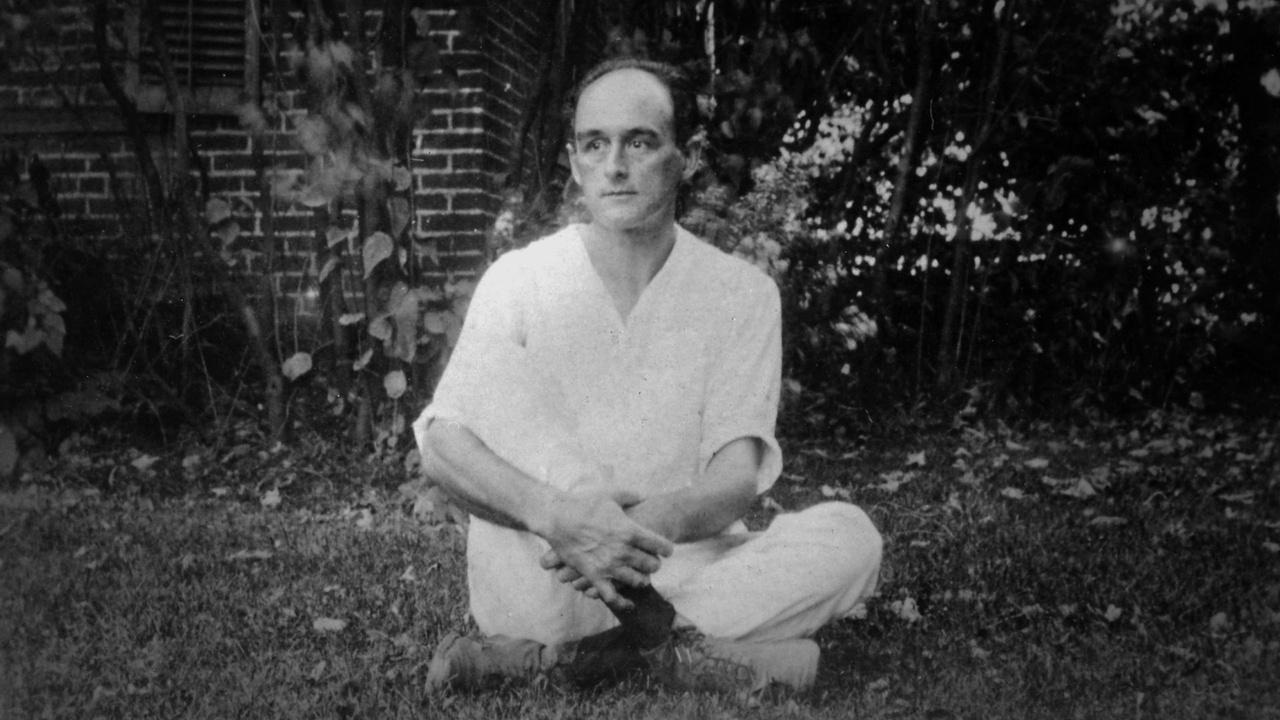

Narrator: In 1934, Hellum met Bob Neal. Through a shared passion for old buildings, a life partnership would develop. In a letter sent right after their meeting, Hellum gushed, “Bob Neal, just the name makes the weekend seem like make-believe!” The two men lived at a time when they needed to keep their love for each other a secret. However, the life’s work they built together would draw attention and admiration for generations.

[elegant piano]

In the early 1800s, prospectors swarmed Southwestern Wisconsin in search of lead ore. They dug caves into the hillsides, reminiscent of badger holes, earning the namesake the ‘Wisconsin Badgers.’ In the 1830s, Cornish immigrant miners settled in the boomtown of Mineral Point, building tiny stone cottages for their family homes.

Will Fellows: These were very small, modest dwellings, some of which seemed to almost grow out of the bluff behind them.

Narrator: By the mid-1930s, the cottages had been long abandoned. They were being torn down for their materials. But where others saw ruin, Edgar Hellum and Bob Neal saw beauty.

Edgar Hellum: Bob said, “I’ve found a house,” but he said, “It’s so decrepit.” He said, “I don’t know whether it can be fixed or not. Can you come over and take a look?” And he had found Pendarvis House. Oh, God, it was awful!

[chuckles heartily]

Narrator: So, for ten dollars and a dream, the two men purchased the cottage and set about restoring it.

Will Fellows: People thought they were kind of nuts. These two young men down on the slummiest street in town living together in one of these rundown stone cottages a lot of people thought should just be knocked down.

Dick Wagner: It was an unusual thing to happen in a small Wisconsin town. They were often described as artistic young men, and it probably was true in that you had to have some sense of what could be, which is what artists do is they create something out of almost nothing.

Narrator: After many months of working sixteen-hour days, Hellum and Neal had restored the home to its 1800s aesthetic. They gave it the Cornish surname ‘Pendarvis.’

Will Fellows: Bob and Edgar were thrilled but needed to make some sort of a living from it.

Narrator: They started with opening a small tea room at Pendarvis. But it soon evolved into a quaint restaurant, embracing the historic identity of the locale. For their signature dish, Bob Neal turned to his family’s old Cornish recipes and landed on the pasty.

Will Fellows: Even though the food itself was very basic, almost kind of like a peasant food in a way, there was a touch of finesse to the meal.

Edgar Hellum: We made the best pasty that anybody made in Mineral Point. We used top-grade beef. We had a good crust recipe, and then, it had to come right from the oven to the table. Simple farm fare, but we did it with a touch of class.

Will Fellows: The focus was not fine dining. The focus was the experience.

Narrator: A pasty was served with a flourish for the table to share while Bob Neal told tales of the Cornish miners who had settled old Mineral Point.

Dick Wagner: Bob Neal clearly had a vision for what heritage tourism could be.

Narrator: By the late 1940s, Pendarvis House restaurant had become a niche destination. The tiny operation received national visibility after being included in an influential travel guide written by food critic and later cake-box celebrity Duncan Hines.

Edgar Hellum: Duncan Hines, he said, “Don’t change a thing, don’t change a thing.”

[laughs warmly]

Narrator: Over the next several decades, Neal and Hellum acquired additional stone cottages in Mineral Point. A restoration project that became their life’s work, and one of Wisconsin’s most-visited historic sites.

Dick Wagner: Pendarvis really sparked and grew historic tourism here in Wisconsin.

Will Fellows: Gay men made an extraordinary contribution in preservation. Both Warner and Bob Neal and Edgar Hellum, they were really early advocates for cultural tourism.

Narrator: The two men complemented each other. Neal handled the food and championed Cornish lore, while Hellum brought the old buildings back to life. Though it was an age when they needed to keep their love for each other a secret, their shared vision and artistic endeavor endures to this day.

Dick Wagner: It’s a remarkable story of how two gay men led their lives to create this artistic and historic place. It’s not just part of the Cornish lore, but it’s part of the gay history of the state.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us