Wisconsin's Vietnam Veterans Present Complex And Personal Portraits

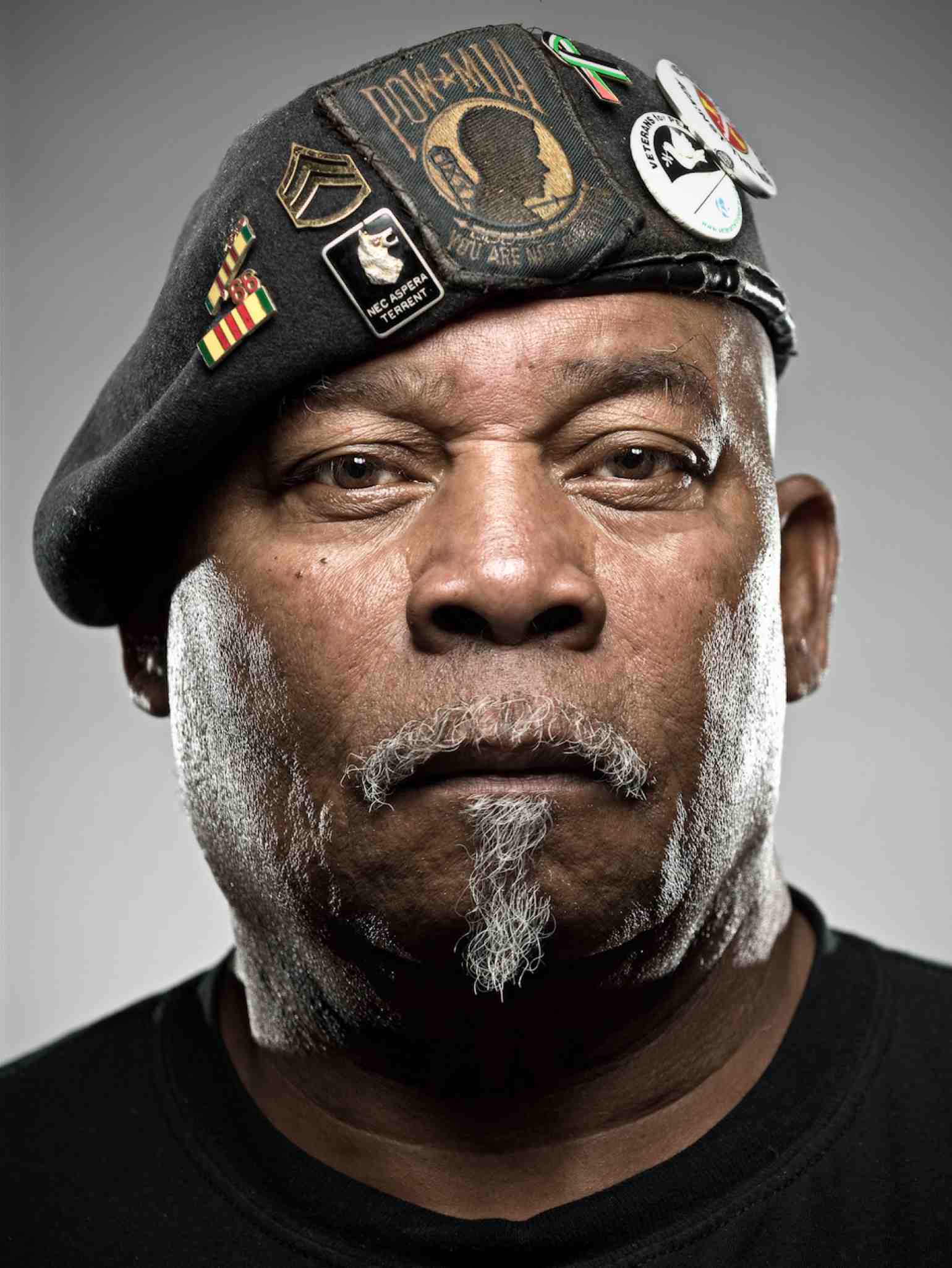

The indelible imprint of the Vietnam War and the myriad marks it left on the lives of those people who experienced it is impossible to miss in a series of veteran portraits by photographer James Gill.

September 19, 2017

James Gill portrait of Bruce Jensen for Wisconsin Vietnam War Stories crop

American veterans of the Vietnam War served in a long, grueling, squalid and horrific conflict that killed more than 58,000 of their fellow U.S. troops. At home, the war became deeply unpopular and inspired a protest movement of historic scale. Those who survived it have often felt less honored and, well, less listened to than veterans of previous wars. They came home to a wide variety of lives and future paths, and would develop philosophies that reflected the imprint of their wartime experiences in wildly different ways.

The indelible imprint of war and the myriad marks it leaves on the lives of those people who experience it is impossible to miss in a series of veteran portraits by photographer James Gill. These images were central to Wisconsin Vietnam War Stories, a three-part documentary by Wisconsin Public Television that originally aired in 2010. The project recounted the experiences of Vietnam veterans from around the state. Posed but starkly unglamorous, these portraits drive home the fact that Vietnam veterans are ordinary people who found themselves at the center of an extraordinarily painful period in modern history.

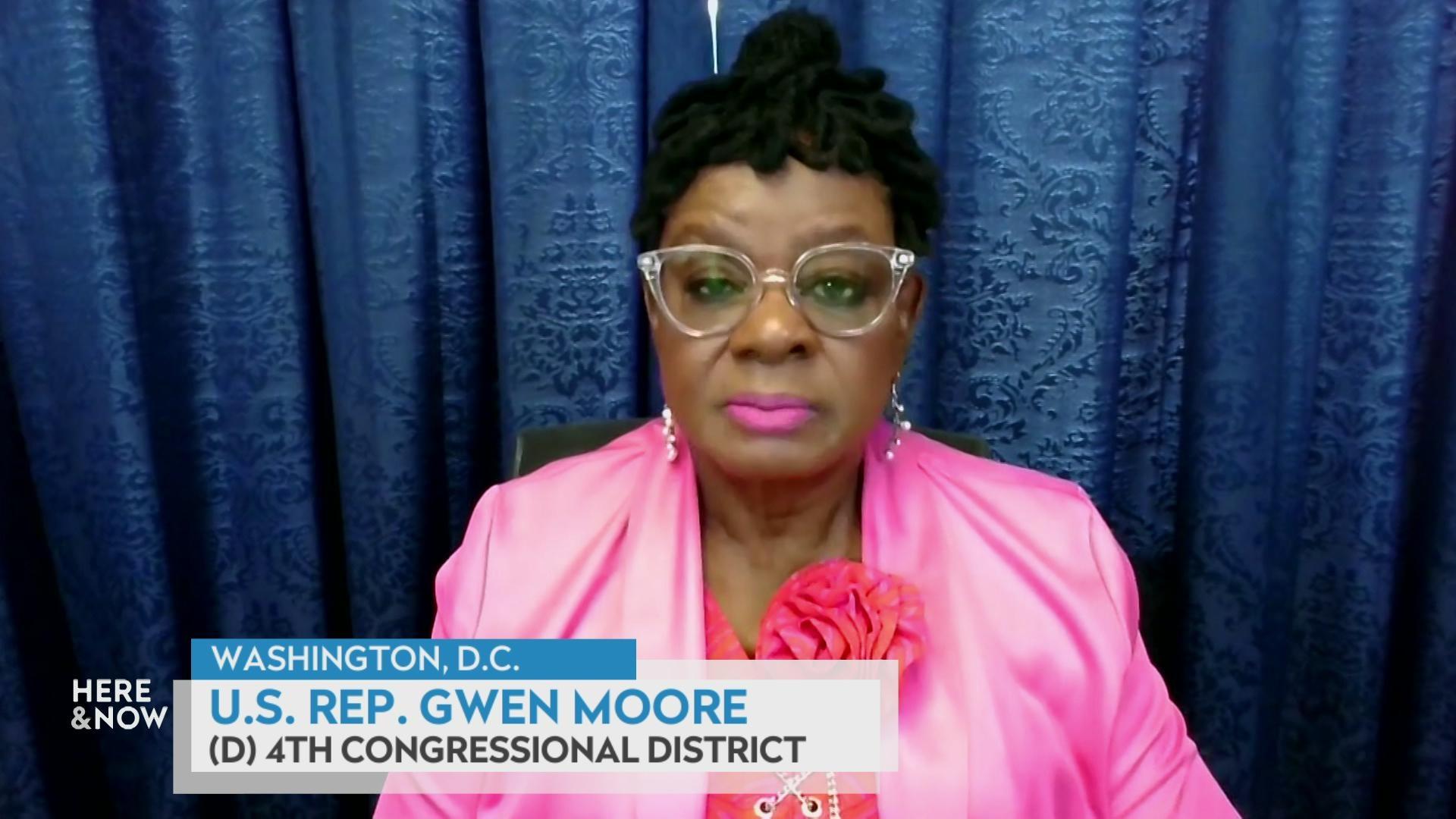

As the staff photographer for Wisconsin Public Television, Gill spoke briefly about his work on the photo portraits at a Nov. 11, 2009 event at the Chazen Museum of Art in Madison before introducing a panel of Wisconsin Vietnam veterans who reflected upon their experiences. George Banda served as a combat medic in the US Army’s 101st Airborne Division. Bruce Jensen served as a gunner’s mate on the US Navy’s USS Stone County in the Mobile Riverine Force. James Kurtz served as a platoon leader in the Army’s 1st Infantry Division. Rev. Ray Stubbe served as a Navy chaplain during the Battle of Khe Sanh. Will Williams served a staff sergeant in the Army’s 25th Infantry Division. Their discussion was recorded for Wisconsin Public Television’s University Place.

The five veterans discussed the horrors and numbing effects of combat, the incredible moments of humanity they witnessed during their service, and how they’ve processed their experiences in the decades since they completed their tours of duty. Their activities have ranged from anti-war organizing to efforts to reconnect with fellow veterans to even revisiting Vietnam in search of a sense of closure. Much as American society has struggled to understand the Vietnam War’s tangled legacy over the past half-century, these veterans’ reflections embody that complexity in a personal way.

Key facts

- One of the most influential modern American portrait photographers, Richard Avedon, created giant portraits of key figures of powerful figures in U.S. government and society in 1976 to mark the nation’s bicentennial. These photos included multiple members of President Richard Nixon’s administration who were key figures in the Vietnam War. These photos were published in Rolling Stone magazine in a gallery titled “The Family.”

- George Banda talked about the difficult experience of losing combat friends, especially a close friend he bonded with who was a fellow Milwaukee native. Banda also spoke about the loneliness he experienced while going off to war, but also while transitioning back to civilian life.

- Bruce Jensen discussed the Mobile Riverine Force, a joint Army/Navy campaign that aimed to clear Viet Cong presence along the Mekong River and its tributaries. He said the force used concepts that were first developed during the American Civil War.

- Rev. Ray Stubbe recalled spending a three-month period where each person in his unit received one cup of water and one combat ration per day.

- Will Williams said that his Veterans for Peace chapter once applied to participate in a Veterans’ Day parade in Milwaukee, but was denied because organizers considered it a “political” group.

- The panelists discussed their use of the phrase “don’t mean nothing” or “don’t mean anything,” which signifies a non-judgmental, we’re-all-in-it-together attitude toward what happened in combat.

- Some soldiers interviewed for the project spoke about not understanding what they were fighting for, so it came down to fighting to stay alive and keep each other alive.

- A lot of the veterans interviewed for Wisconsin Vietnam War Stories told interviewers that very few people had previously shown interest in hearing about their experiences. Several of the panelists discussed this lack of curiosity, attributing it to the unpopularity of the Vietnam War and the disconnect between traumatized veterans and the general public.

Key quotes

- Gill on sacrifices made by these veterans: “I think that we have forgotten what makes this country great. It is not the sports stars, movie heroes or politicians. In reality, they are not any better or worse than the guy who works at PDQ or the grandmother who packs your purchases at Wal-Mart. That is why portraying these veterans as they are was so important to me. They are real Americans who have given up a part of their lives, and sometimes much more, for the rest of us.”

- Gill on his intentions with the photos: “The portraits in this exhibit are meant to confront you. They are not pretty pictures. There is no pretense that these would be used in a Christmas card. The veterans don’t have a mask of a smile to hide behind, or to lead you away from their true identity. With that stripped away, my hope is that these images and words can show you a glimpse into the reality of their Vietnam experience.”

- Banda on public discourse about starting and getting more involved in wars: “I wouldn’t want to put anyone through what I went through — no one. … You protest, you vote, you get out there and you tell people, ‘Hey, wait a minute, this isn’t what we should do. Let’s think this over a little bit.'”

- Jensen on the role humor played in his unit: “In Vietnam, in the [Mekong] Delta, it was a way of coping. I was the practical joker on our boat. Nobody knew what to expect from me. But I kept them laughing and I kept their minds off of anything, the bad things.”

- Kurtz on his and others’ service in Vietnam: “Most of the people that served before 1968 expected to serve. Because as we were growing up, the draft was very much a reality. Our fathers and uncles and brothers were either in World War II or Korea. And so that was just part of the passage of the males up until about that time. Then when the war — after Tet happened — and it was clear that we were leaving, the draft in some ways became fairer because they started, the deferments and all of that were gone. But yet, it’s a very hard thing to do for people to go into a war zone and know that the country didn’t support them and that they might be, as John Kerry said, the last person to die.”

- Kurtz on pride as a Vietnam veteran: “It’s taken a while for them to have that feeling of pride. Most of them that I talk to had not had any conversations at all about their Vietnam experiences until we had these things.”

- Kurtz on a disconnect between veterans and governing elites: “Examine what happened with the run-up to Iraq. The people who made the decision, none of them served. None of them served. And it’s only if we have people who have had the experience to understand how awful war is. We’re going into a situation right now where pilots are becoming obsolete and we’ve got people in Las Vegas flying combat aircraft. We need to have people who understand how bad war is.”

- Stubbe on camaraderie between troops in the war: “These are mainly young people, about 19-, 20-year-olds, who, you see their real humanity coming out in these terrible, terrible, terrible times of carrying out people that you know are dying or don’t have a head, or whatever, anymore… people would give their last drops of water to somebody else.”

- Stubbe on being a chaplain under heavy artillery fire: “I would go from bunker to bunker and trench to trench. Couldn’t hold church services, but we could gather four or five people at once and have maybe a short prayer or whatever — I could hug them, they could hug me. We could say what’s going on, how things are. They could tell jokes about their girlfriend back home, or whatever. That’s another thing, there was so much humor going on at this time. You know, a rocket would explode right out front, like the first row from the table here. And someone would say, ‘Oh, those NVA gunners, they’re piss-poor, look at that they can’t even fire accurately on our bunker!’ Not realizing the rocket was fired maybe five miles away.”

- Williams on feeling a bond with fellow veterans but being involved in anti-war activism: “I’m not proud of what I did in Vietnam, because through time and reading and finding out the truth about why we went to Vietnam, it made me angry about it. And I’m not proud of it. But that bond, I think it can’t be broken, in a sense.”

- Williams on the transformation of the Nov. 11 national holiday from Armistice Day into Veterans Day: “It wasn’t until 1954 when it became Veterans Day with Eisenhower’s signature. So I think that day might have been a beginning of the glorification of war, rather than looking at what war do to the people and the people that fight it. So I feel we’re treated different because I am with Veterans for Peace, because that legislation didn’t say, ‘It’s for veterans who fly the flags and tie ribbons around trees’ or if it’s veterans that speak out for peace. It said all veterans.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us