Wisconsin Supreme Court Confirms Time Limit on Governor's Emergency Powers

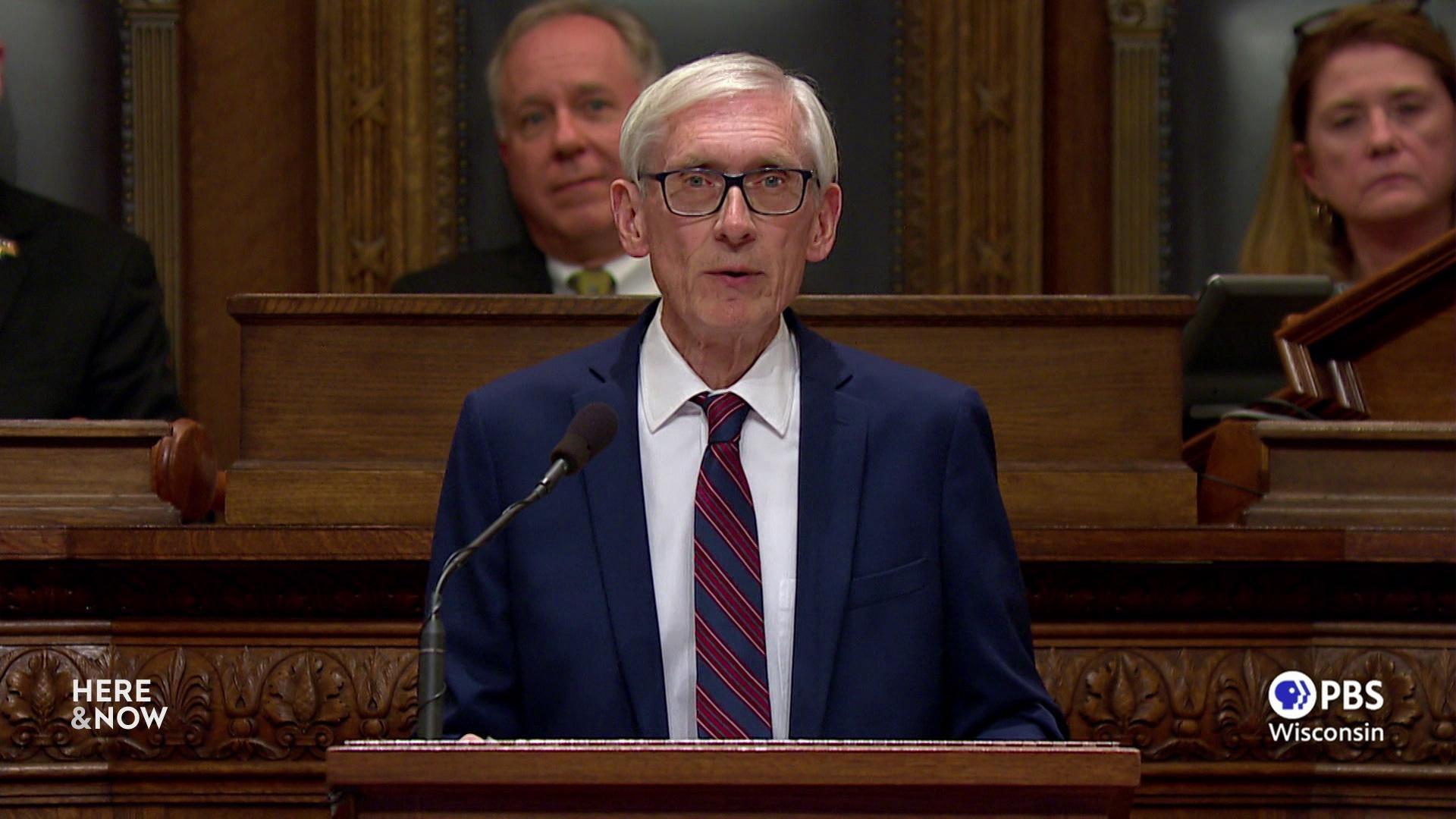

The 4-3 conservative majority on the state's high court ruled the initial emergency order issued by Gov. Tony Evers in response to COVID-19 applied to the pandemic as a whole, and subsequent declarations were unlawful, overturning the statewide mask mandate.

By Will Cushman

March 31, 2021

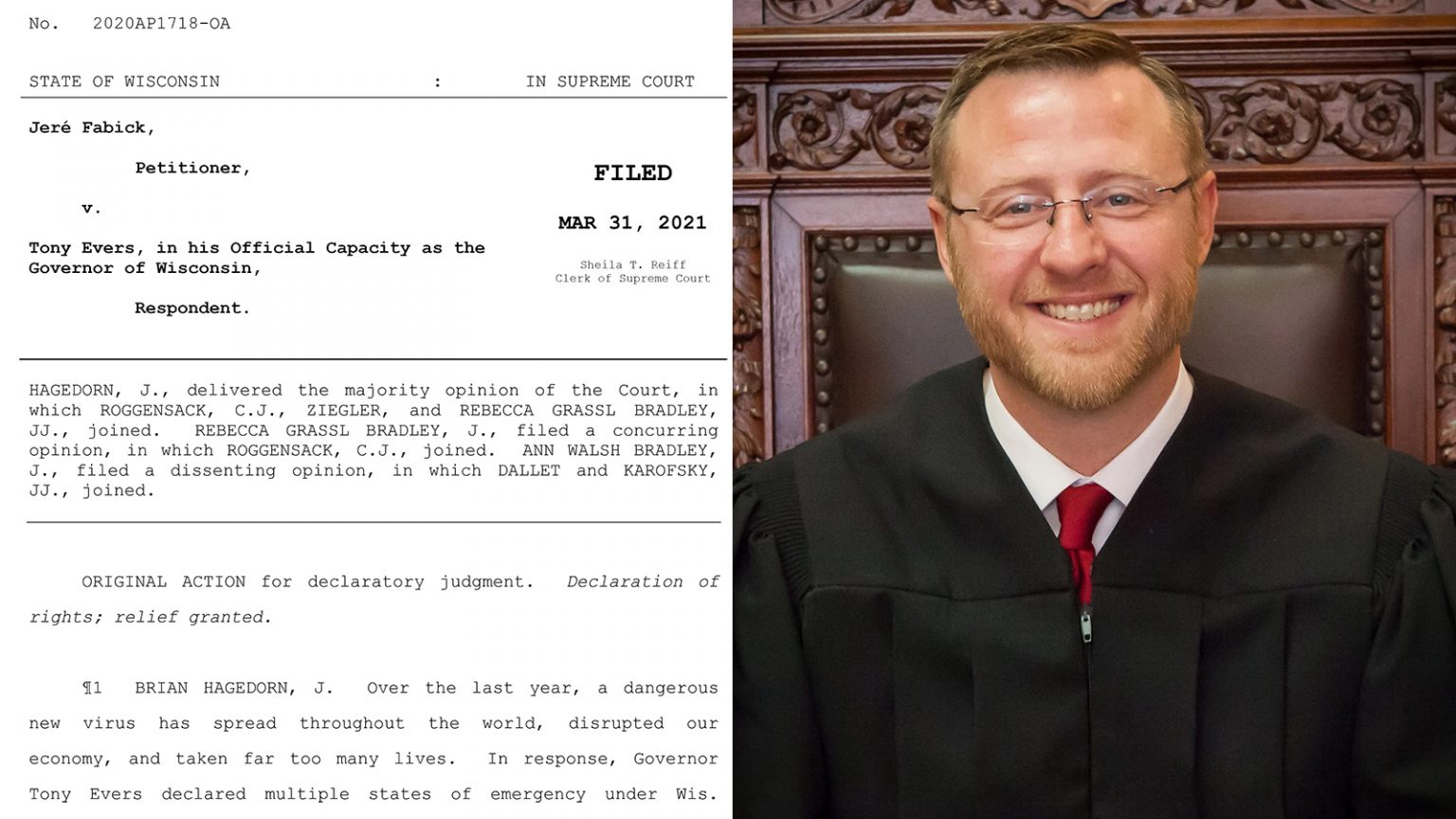

Justice Brian Hagedorn wrote the ruling of a 4-3 majority of the Wisconsin Supreme Court in Fabick v. Evers, a lawsuit challenging the governor's declaring multiple public health emergencies in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. (Credit: Courtesy of the Wisconsin Supreme Court)

Cleaving along standard ideological lines, a closely split Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled Wednesday that Gov. Tony Evers doesn’t have the power to declare multiple public health emergencies in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The 4-3 decision, with the court’s conservative bloc in the majority, carried an immediate effect of overturning Wisconsin’s statewide mask mandate.

The fate of the mask mandate, in effect since August 2020 under multiple public health emergencies declared by Evers, was not the only consequential item affected by the court’s action. Its decision could also preclude the state from qualifying for federal assistance for the state’s FoodShare program valued at nearly $50 million per month.

Delivering the majority opinion, Justice Brian Hagedorn wrote the court’s decision was not a judgement of the prudence of Evers’ emergency declarations or mask mandate.

“The question in this case is not whether the Governor acted wisely; it is whether he acted lawfully,” Hagedorn wrote. “We conclude he did not.”

At issue in the case filed by construction equipment dealership owner and conservative activist Jeré Fabick are the limits of emergency powers granted to the state’s executive branch under state law. The statute grants the governor the ability to issue executive orders declaring states of emergency in response to disasters or public health crises.

The law places limits on the governor’s emergency powers, though. States of emergency automatically expire after 60 days unless extended by joint resolution of the Legislature. Lawmakers can also revoke an emergency order by joint resolution before it expires.

Evers first declared a public health emergency in response to COVID-19 in March 2020, authorizing the Wisconsin Department of Health Services to exercise emergency powers to more nimbly respond to the emerging pandemic. That executive order expired in May. Fabick argued successive public health emergencies Evers declared in response to rising COVID-19 caseloads in the state amounted to unlawful extensions of the original order because they were all ultimately in response to the pandemic.

Hagedorn, joined by Chief Justice Patience Roggensack and Justices Rebecca Bradley and Annette Ziegler, agreed.

“The statutory language suggests the Legislature gave the executive branch expansive, but temporary, authority to respond to emergencies,” Hagedorn wrote in the majority opinion. “When the governor employs those powers beyond the time limits imposed by the Legislature, or after revocation of those powers by the Legislature, he wields authority never given to him by the people or their representatives.”

The decision had the immediate effect of voiding an executive order issued Feb. 4, 2021, declaring a public health emergency, along with an accompanying emergency order requiring face coverings for anyone 5 and older in enclosed public spaces. Both were set to expire April 5.

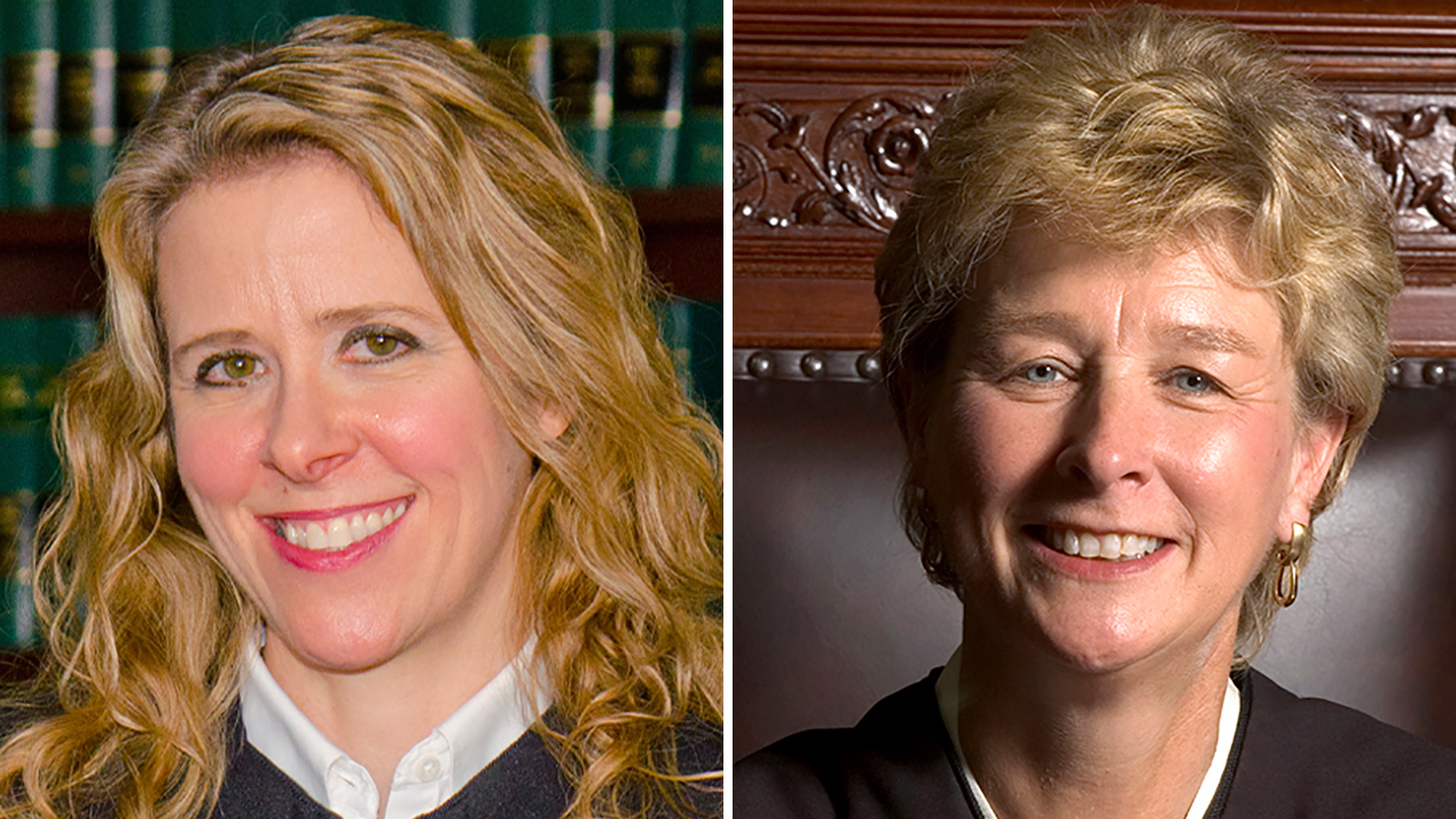

While the majority opinion decided the case based on its interpretation of the wording of state law, a concurring opinion penned by Justice Rebecca Bradley and joined by Chief Justice Roggensack was more philosophical in its reasoning.

Quoting heavily from the Federalist Papers and other sources from the early years of the United States, their concurring opinion centered on the separation of powers enshrined in the U.S. and state constitutions. Bradley and Roggensack lamented what they termed as the state Supreme Court’s “ever-evolving abandonment” of separation-of-power principles since the early 20th century, which they wrote has resulted in too much legislative power being delegated to the executive branch.

They wrote Evers’ interpretation of his emergency powers amounted to a violation of the separation of powers and was therefore unconstitutional.

“Governor Evers’ construction of [Wisconsin law] would leave the exercise of extraordinary power entirely to the judgment of the executive, unlimited in duration,” Bradley wrote. “As the Governor would have it, so long as he alone thinks the cause of a public health emergency persists, he retains the unchecked power to keep Wisconsin in a perpetual state of emergency.”

In a dissent, the court’s liberal wing denounced the majority decision on multiple levels. Writing for the minority, including Justices Rebecca Dallet and Jill Karofsky, Justice Ann Walsh Bradley said the state Supreme Court should never have heard the case in the first place because she said Fabick did not have taxpayer standing, a prerequisite to take up the case.

To have taxpayer standing, Fabick needed to demonstrate he incurred a monetary loss as a result of Evers’ emergency declarations. Fabick argued he incurred a monetary loss as a Wisconsin taxpayer because the state was originally responsible for paying 25% of the cost of activating the National Guard to respond to the pandemic. However, in January, President Joe Biden signed an executive order covering the cost of National Guard activation for COVID-19 response entirely through federal coffers, both retroactively and going forward.

In the majority decision, Hagedorn wrote Fabick could maintain taxpayer standing because federal policies could shift yet again in the future, creating a “threat” of monetary loss.

In the dissent, Walsh Bradley wrote that reasoning was flawed.

“The majority errs by granting taxpayer standing to Fabick on a conjured justification neither briefed nor argued by any party,” she wrote. “In essence, the product of this new theory results in a standard so low that all that is needed for taxpayer standing in this court is a song and a whistle with an ability to produce a melody appealing to at least four justices.”

Walsh Bradley wrote the majority’s interpretation of state statutes outlining governors’ emergency powers was also flawed. She zeroed in on the statutory definition of a public health emergency: “the occurrence or imminent threat of an illness or health condition” that meets certain criteria.

While the ruling concluded the pandemic satisfied these criteria and Evers’ original public health emergency declaration was lawful, it argued that subsequent declarations were unconstitutional due to the 60-day limit in state law.

On the other hand, the dissent agreed with Evers’ argument that subsequent declarations were in response to discrete “occurrences” of illness, those occurrences being different surges in COVID-19 infections resulting from separate factors such as, the minority asserted, the beginning of the school year.

Walsh Bradley wrote Evers’ emergency declarations in July and September were “premised on statutory occurrences that are distinct from each other and from that relied upon for [the original order]. Therefore, they are permissible pursuant to the Governor’s authority under [Wisconsin law].”

Echoing a brief filed on behalf of the Evers administration, Walsh Bradley compared the evolving COVID-19 pandemic to changing conditions following a natural disaster.

“Imagine heavy rains leading to a flood that two months later causes a dam to break. If the governor declared a state of emergency because of the initial flooding, he could not issue another for the new flood caused by the dam failure because it shares an underlying cause with the previous state of emergency,” Walsh Bradley wrote. “This simply could not be the Legislature’s intent.”

In response, Hagedorn wrote that interpreting state law to permit new emergency orders as the threat of the pandemic evolves “reads the duration limitations right out of the law.”

“A governor will surely have little difficulty drafting a new emergency order stating that the challenges or risks are a little different now than they were last month or last week,” he wrote.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us