Wisconsin debates cash bail changes in wake of Waukesha parade tragedy — as some states ditch system entirely

Somewhat lost in a revived debate involving the rights of the accused and protecting the public: Wisconsin's cash bail system wasn't created to protect public safety.

Wisconsin Watch

January 18, 2022 • Southeast Region

Darrell E. Brooks appears in Waukesha County Circuit Court on Jan. 14, 2022 in Waukesha. Brooks is accused of killing six people and injuring dozens more while driving an SUV through a suburban Christmas parade. A series of mix-ups led Brooks to be released from jail on Nov. 16 on an unusually low cash bail. (Credit: Derek Johnson / The Waukesha Freeman)

By Clare Amari, Wisconsin Watch

Darrell E. Brooks had been out of jail for just five days when he allegedly plowed a red Ford Escape into a Christmas parade in Waukesha in November, killing six people and injuring dozens more.

A series of mix-ups led Brooks, 39, to be released from jail on Nov. 16 on an unusually low cash bail after a case in which he allegedly used the same SUV to run over a woman after battering her.

As a prosecutor prepared to recommend bail, she lacked access to the results of Brooks’ risk assessment — a tool to help determine his likelihood of reoffending or failing to appear for his next court date. That information was not uploaded into a case management system, according to Milwaukee County District Attorney John Chisholm, whose office has faced a torrent of criticism for its handling of the domestic violence case.

The assessment identified Brooks as high risk and listed previous felony convictions and charges in cases involving violence, alongside a “serious persistent illness in which he is not receiving treatment for.”

But facing an overwhelming case load, the prosecutor recommended that Milwaukee County Court Commissioner Cedric Cornwall set Brooks’ bail at $1,000 — an unusually low amount under such circumstances. The bond was posted on Nov. 11. The Milwaukee County Jail released Brooks on Nov. 16 to the Waukesha County Sheriff’s Department, where he was released after a hearing that day in a paternity case.

Less than a week later, Brooks allegedly sped past barricades and into the parade gathering of thousands — transforming a joyous celebration into a mass casualty scene.

The shocking incident left Waukesha residents reeling and revived a debate about bail reform: How do you balance the rights of the accused while protecting the public? A legislative study committee in 2019 introduced a litany of bills to change the system that did not advance in the Legislature.

Somewhat lost in the latest discussion: Under Wisconsin’s Constitution, cash bail is not designed to protect the public — only to ensure the accused’s appearance at the next court date.

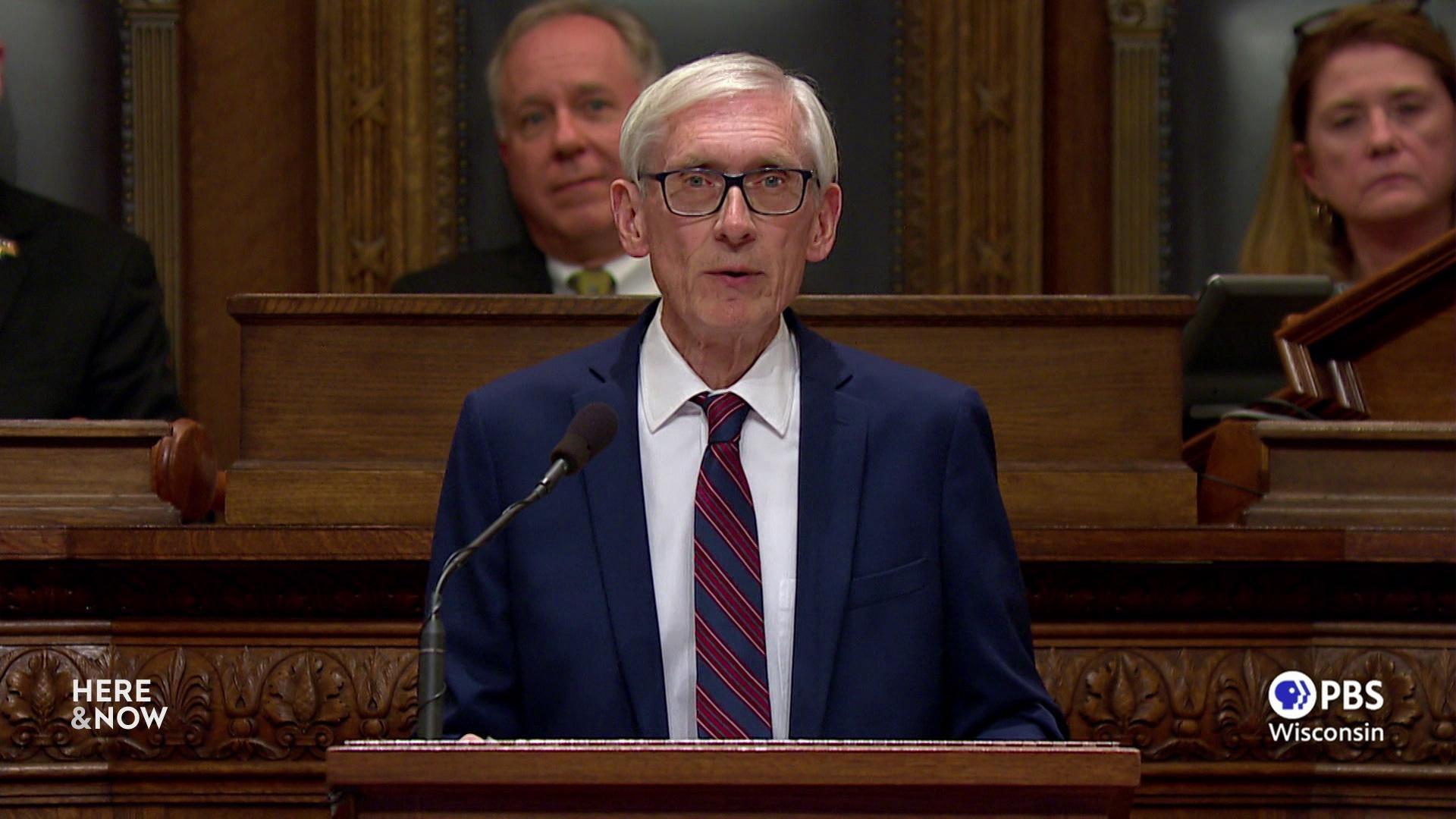

Nevertheless, Republican lawmakers are calling for Chisholm’s ouster and pushing legislation to more frequently jail the accused before trial. Democratic Gov. Tony Evers says he’s open to stricter bail policies, but his office says it currently lacks authority to remove Chisholm, citing a legal opinion.

“Wisconsin lives are in danger because of the low bail that soft-on-crime judges and DAs are currently setting,” state Sen. Julian Bradley, R-Franklin, said in a January 2022 statement. “This revolving door for criminals must end.”

For Bradley, that would include requiring a bond of at least $10,000 for defendants who have been previously convicted of a felony or violent misdemeanor, among a suite of bills he and other Republicans have proposed to tighten cash bail laws.

Sen. Julian Bradley, R-Franklin, is seen during a meeting of the Committee of Judiciary and Public Safety at the Wisconsin State Capitol in Madison on Oct. 14, 2021. Bradley has proposed a bill requiring a bond of at least $10,000 for defendants who have been previously convicted of a felony or violent misdemeanor. (Credit: Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

Such proposals look past fundamental shortcomings in Wisconsin’s cash bail system, critics say. Higher bail may have kept Brooks locked up during the parade, but it would not have prevented a wealthier defendant with a similar track record from leaving jail. A long-standing critique of systems nationwide is that they disproportionately incarcerate low-income defendants and people of color awaiting trial, including for nonviolent offenses.

A few states have virtually eliminated cash bail. They include New Jersey, where data show that defendants are increasingly showing up for court dates and committing fewer serious crimes while awaiting trial. However, other states that have made similar changes, such as Alaska and New York, face significant pushback from critics concerned that eliminating cash bail encourages a spike in crime.

“Release on bail is a risky proposition, and relying on it is a risky proposition, too,” said Lanny Glinberg, an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin Law School. “Because it can function as punishment before due process, but it can also be necessary to ensure public safety. And that can be a difficult balance to strike.”

Some cash bail critics in Wisconsin say smaller changes could better protect public safety. That includes Chisholm, who called his office’s handling of Brooks’ domestic violence case a mistake, blaming “human error” within an overloaded and under-resourced court system. He advocates overhauling Wisconsin’s preventive detention law to allow prosecutors to swiftly argue to detain potentially dangerous defendants without bail.

Milwaukee County District Attorney John Chisholm says he opposes cash bail, and that his office made a mistake in the handling of bail in the domestic violence case against Darrell E. Brooks. Brooks is charged with killing six people and injuring dozens of others when he drove into a Christmas parade in Waukesha. Chisholm advocates overhauling Wisconsin’s preventative detention law to allow prosecutors to swiftly argue to detain potentially dangerous defendants without bail. (Credit: Courtesy of Milwaukee County District Attorney’s office)

“I’m opposed to cash bail,” Chisholm told Milwaukee County supervisors in December. “It doesn’t do a good job of assessing risk.”

Poor locked up, rich go free

Wisconsin did not design its cash bail system to lock up potentially dangerous defendants. The state Constitution says judges may consider only one factor when setting bail: whether a defendant will likely return to court, although judges can weigh safety when adding conditions of release, such as requiring a defendant to wear an ankle monitor.

Wisconsin judges still typically set high cash bails for serious crimes, using the justification that the accused is a high flight risk because he or she is facing a lengthy prison term. Brooks is now in Waukesha County Jail, facing six counts of first-degree intentional homicide among more than 70 other charges, after a judge set bond at $5 million.

But even relatively lower bail amounts — $150 or $200 — sometimes keep low-income defendants in jail while facing nonviolent charges. Meanwhile, judges have few tools to detain rich defendants for violent crimes, retired Milwaukee County Circuit Judge Jeffrey Kremers told Wisconsin Watch in 2019 for a report that examined how the use of cash bail disproportionately keeps the poor behind bars.

“Our only option for someone who we all agree is very dangerous, a super flight risk, is to set high cash bail,” Kremers said. “What I don’t know is that you (the defendant) have a brother who’s a hedge fund manager who comes in and posts the $500,000 and you’re out.”

State Rep. Cindi Duchow, R-Delafield, wants to amend the Wisconsin Constitution to allow judges to consider public safety when setting bail. She recently introduced such a resolution, which would require passage by two consecutive Legislatures before being put on the ballot as a referendum. Sen. Van Wanggaard, R-Racine, authored a Senate version of the resolution.

“It’s really very simple common sense,” said Duchow, who pushed for such changes in two previous legislative sessions — spurred by the release of a man accused of molesting children in her neighborhood. “If somebody commits a crime, let’s see if they are a risk to the community.”

State Rep. Cindi Duchow, R-Town of Delafield, introduced a constitutional amendment to require judges to consider the danger a defendant poses to the community when setting bail amounts. As of January 2022, judges in Wisconsin are only supposed to use bail as a tool to ensure the accused appears for the next court hearing. Duchow is seen at a 2018 meeting of the Legislative Study Committee on Bail and Conditions of Pretrial Release in Madison. (Credit: Emily Hamer / Wisconsin Watch)

The amendment would not address the dilemmas over detaining potentially violent defendants who can afford bail. And critics say adding dangerousness provisions to cash bail could worsen income and racial disparities in Wisconsin’s criminal justice system, which already imprisons one of every 36 Black adults — higher than any other state.

“It just creates more opportunities for people who lack means or people of color to be detained on a variety of charges — and for the racial disparities in the system to increase,” said Meghan Guevara, executive partner at the Baltimore, Maryland-based Pretrial Justice Institute, which advocates for changes in the bail system. “You could have someone who is a significant risk to not show up to court, or to public safety, but if that person has cash on hand, then they’re back in the community.”

Downsides of pretrial detention

Brooks’ case notwithstanding, defendants rarely commit serious crimes when released before trial. In Milwaukee County, 98% of those released to pretrial supervision whose cases were resolved in 2017 did not commit new violent crimes, according to a presentation by Kremers. The only way to prevent all new violent criminal activity among defendants awaiting trial would be to detain everyone. That would be unconstitutional and overflow jails at taxpayers’ expense.

Liberty should be “the norm,” and detention before trial “the carefully limited exception,” according to a 1987 U.S. Supreme Court case.

Meanwhile, studies show that pretrial detention can prove counterproductive.

Researchers have found that spending even a few days in jail awaiting trial in misdemeanor cases correlates with defendants committing more crimes later on and pleading guilty — even if they are innocent. It can also exacerbate poverty and cause defendants to lose child custody or employment. Ironically, research shows defendants detained pretrial for even brief stays are less likely to show up for court than defendants not detained.

New Jersey bails on cash bail

New Jersey opted for a risk-based pretrial detention system in ditching cash bail in 2017, seeking to prioritize public safety — and not a defendant’s ability to pay, according to a 2021 report to the New Jersey Governor and the Legislature. The rate of New Jersey defendants charged with serious offenses while on pretrial release dipped to 0.4% from 1.6% from 2017 to 2019. Court appearance rates jumped to nearly 91% from just over 89% during the same period.

New Jersey relies heavily on a screening tool called the Public Safety Assessment (PSA), a computer algorithm that uses defendants’ criminal history and past performance in court — among other factors — to predict the risk of them committing a new crime or failing to appear in court. It’s the same type of assessment that Chisholm’s office overlooked in recommending Brooks’ bail. At least nine other Wisconsin counties use PSAs, according to a 2020 Wisconsin Supreme Court survey. Eight other counties said they use different pretrial risk assessment tools.

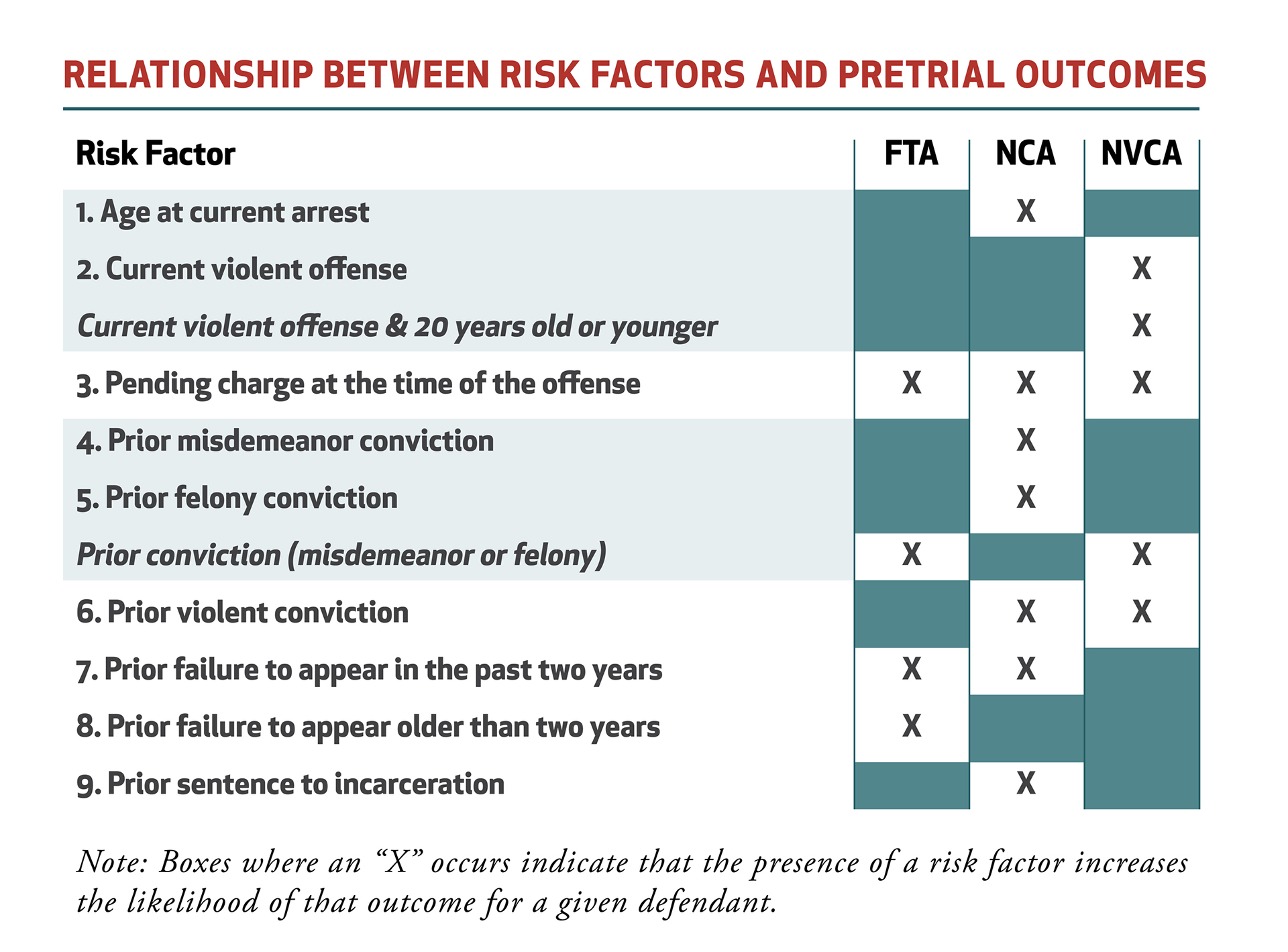

These are the nine risk factors that the Public Safety Assessment uses to predict how likely a defendant is to fail to appear (FTA), commit new criminal activity (NCA) and commit new violent criminal activity (NVCA). The Laura and John Arnold Foundation found these factors to best predict risk based on an analysis of 750,000 cases from 300 jurisdictions across the United States. (Credit: Courtesy of the Laura and John Arnold Foundation)

But the use of those tools in Wisconsin make up just one component of a bail recommendation — in contrast to New Jersey, which has removed money from the equation.

New Jersey’s shift has reshaped jail populations, driving a “sharp decline” in low-risk defendants who could not otherwise afford bail while boosting the proportion of defendants facing serious offenses, according to the New Jersey report. The overhauled system, unlike its predecessor, also allows for the detention of domestic violence offenders like Brooks — regardless of their financial status. Domestic violence is seen as a predictor of more violent crimes like mass shootings.

Risk tools draw critics

Still, risk assessments remain an imperfect tool for solving pretrial incarceration dilemmas.

“The risk assessment instruments, like human decision-making, have a very hard task that so far nobody has cracked very well — (to) precisely band people into risk levels,” said Chris Griffin, director of empirical and policy research at the University of Arizona law school. Griffin is studying the impact of risk assessments in Dane County.

The Pretrial Justice Institute reversed its support for risk assessments over concerns that they exacerbate racial disparities. The assessments “rely on data related to prior arrests and prior conviction, and there’s so much racial bias baked into that data in every community in the country,” Guevara said.

Meghan Guevara, executive partner at the Baltimore, Maryland-based Pretrial Justice Institute, says the cash bail system worsens income and racial disparities in the criminal justice system. In 2020, the Pretrial Justice Institute reversed its support for risk assessments over concerns that they exacerbate racial disparities. (Credit: Courtesy of Meghan Guevara)

Racial disparities persist in New Jersey’s reworked criminal justice system, with Black people comprising 60% of the statewide jail population in 2020 compared to just 15% of the total population, according to the state report.

Chisholm advocates changing the state’s preventive detention law to keep potentially dangerous defendants in jail without bail. Echoing other criminal justice officials, he called the current version “simply unworkable” due to procedural flaws.

Detaining a defendant under the current law, he said, would require “the equivalent of a court trial” within 10 days of taking the defendant into custody — an insurmountable barrier for prosecutors.

“The simple solution is to allow us to argue, honestly, to the judge, to the court commissioner, why it is that we think somebody should not go back out into the community, and then that person would be detained,” Chisholm said. “That case would be expedited, and you would prioritize getting that case resolved.”

Duchow said she could back a preventive detention overhaul, which would likely also require a constitutional amendment.

Any such changes should include “stringent requirements” for prosecutors to argue for detention for a narrow group of serious charges, Guevara said, with on-the-record decisions open to public scrutiny.

But even the most effective bail changes won’t necessarily prevent rare events like what happened in Waukesha, Guevara added, unless communities address the underlying causes of violence.

“We’re often very quick to pay for new jails or to pay for other criminal justice interventions, whereas our mental health systems and other supportive systems are woefully lacking,” she said. Addressing Brooks, she asked: “Did something else need to happen earlier to disrupt the trajectory of what’s going on with this man’s life?”

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us