Why It's Difficult To Gauge The Effects Of Wisconsin's FoodShare Work Rules

As work-related eligibility rules for Wisconsin's food stamp program expand, it remains unclear to what extent the requirements already in place are having their intended effect.

By Will Cushman

February 26, 2019

Cart in grocery store floor-level view illustration

As work-related eligibility rules for Wisconsin’s food stamp program expand, it remains unclear to what extent the requirements already in place are having their intended effect: namely, to nudge able-bodied adults into employment that could replace their need for food assistance.

Wisconsin’s program, named FoodShare, is funded through the federal Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program, or SNAP. Since 1996, the federal government has required states to attach work requirements to SNAP benefits for some able-bodied adults, though many states have secured waivers for this provision over the years.

Wisconsin held a waiver from 2002 until 2015, when then-Gov. Scott Walker and the Republican-led Legislature reinstated the work requirement, citing Wisconsin’s post-recession economic recovery and low unemployment. Walker and the Legislature followed that up in 2017 with an expansion of that work requirement, scheduled to take effect in October 2019.

Since 2015, Wisconsin has required able-bodied adults younger than 50 who do not have dependents to follow federal work requirements in order to maintain FoodShare benefits beyond three months over a three-year period. These requirements stipulate able-bodied recipients to spend 80 hours a month working, participating in a state-sanctioned workforce training program, or doing a combination of the two.

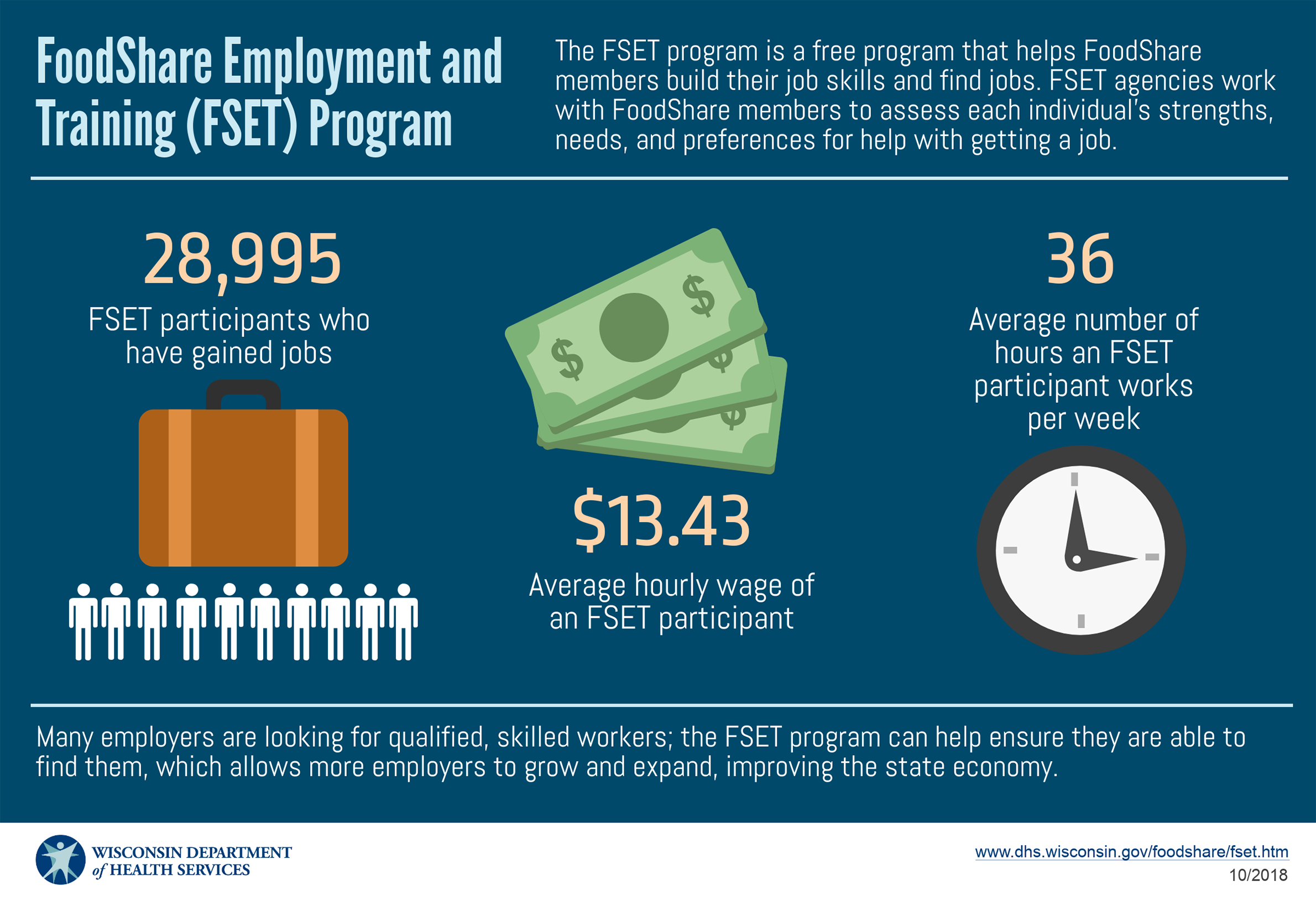

FoodShare Employment and Training, commonly known as FSET, is the primary workforce training program that FoodShare members take part in to meet the work requirement. Created in 2008, the program is free for FoodShare recipients, and data from the Wisconsin Department of Health Services show that more than 30,000 participants have secured employment between April 2015, when the work requirement was reinstated, and September 2018.

Over the same time, around 84,000 FoodShare recipients have lost their benefits, according to David Lee, the executive director of Feeding Wisconsin, a statewide association of food banks. But it is unclear how many of those 84,000 former FoodShare members have found jobs, either through FSET, other training or on their own.

It’s similarly difficult to gauge how well FSET is preparing FoodShare members for the workforce and eventual self-sufficiency, even as the state is preparing to expand its work requirement from 20 to 30 hours per week and expand to cover able-bodied parents of school-aged children.

Lee said the expanded requirements could very well kick more people off FoodShare after it takes effect.

“I think when we were doing some of our client engagement over the last year, what we’ve learned is that there are a lot of folks in communities across the state who are working, just not working enough hours to comply with the extended work hours,” Lee said in a Feb. 15, 2019 interview on Wisconsin Public Television’s Here & Now.

“So you might have somebody working at a convenience store 20, 25 hours, 28 hours a week, but they can’t get those last two hours to comply with … this new 30-hour work requirement,” Lee added

The additional requirements will make FSET all the more important to thousands of FoodShare recipients, and the state is doubling its investment in the program to $107 million per year. Much of those funds will go to the seven vendors around the state that operate local FSET workforce trainings.

The effectiveness of FSET may remain opaque because in 2017, Walker vetoed a provision passed by the Legislature that would have required a pilot and evaluation of the FSET expansion.

The lack of a rigorous evaluation “makes it really impossible to track the effectiveness of FSET,” Lee told WisContext in a follow-up interview. Noting the large gap between FoodShare members being rejected benefits for not meeting work requirements and the number known to have found jobs through FSET, Lee said the program “doesn’t feel super effective.”

If the goal of FSET is to help FoodShare members achieve economic self-sufficiency, Lee said the data available don’t paint a very rosy picture so far. The average hourly wage of FSET participants stands at $13.43.

“These are still low-wage jobs that aren’t family supporting,” Lee said.

WisContext has reached out to the Department of Health Services to ask how it evaluates FSET, but has not received a response.

DHS has solicited advice on how to best evaluate FSET, however, and received a detailed analysis and set of recommendations in 2018.

Those recommendations are part of a policy paper by graduate students at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s La Follette School of Public Affairs. The paper details major challenges to evaluating FSET even if there were a state mandate. These challenges include the training programs’ decentralized structure and differences in programming offered by the various vendors throughout the state, as well as significant challenges that are inherent to rigorous social science techniques, like identifying an appropriate control group to compare results against.

The authors made several evaluation recommendations. They range from relatively simple changes, like standardizing how FSET vendors use funds, to those that are expensive and time-consuming, like streamlining data reporting. They did not place a price tag on their recommendations, but do note that an ideal evaluation would be costly.

J. Michael Collins, an associate professor in the La Follette school, advised the graduate students’ work on the paper. He said the challenges to evaluating FSET are significant, but if the state truly wants a successful program, it’ll need to address them.

“If you’re going to implement a policy goal, shouldn’t there be some accountability on the implementation?” Collins said, though he added that no other states with similar work requirements have been able to evaluate their success, so far as he is aware.

“Monitoring and evaluating success of these policy programs is really hard,” he said.

Without a more rigorous evaluation of FSET, including evaluations of the barriers to access and effectiveness of trainings, Lee suggested the state could end up spending hundreds of millions on expanding the program without understanding if it’s helping or hurting the individuals it’s meant to serve.

“It would help the state to understand the population of folks who are being affected by this policy,” he said.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us