Why Did Evers Veto An Update to Withholding Tables After a Tax Cut?

The governor approved income tax cuts included in the state's 2021-23 budget but vetoed a provision that would have required the Department of Revenue to immediately adjust tax withholding levels, raising questions about the rationale behind this action.

By Zac Schultz

July 15, 2021

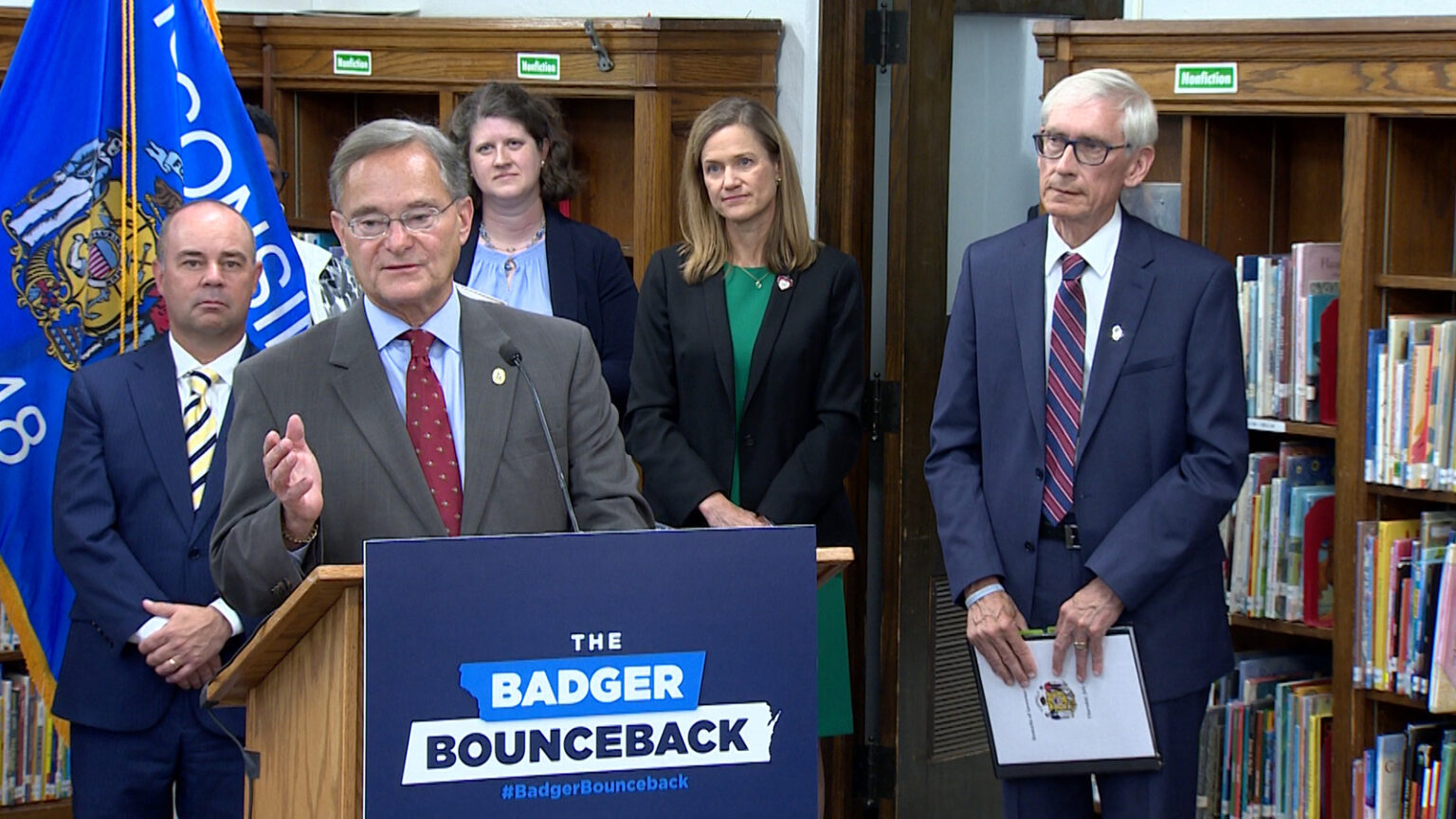

Wisconsin Department of Revenue Secretary Peter Barca speaks at the 2021-23 budget ceremony held July 8 at Cumberland Elementary School in Whitefish Bay, surrounded by Gov. Tony Evers and other members of the governor's administration. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Governor Tony Evers and Republicans in the state Legislature have made a show of highlighting tax cuts in Wisconsin’s 2021-23 budget. Even as the state income tax rate is going down, workers won’t automatically see a boost in their take home pay. That’s because the governor used his partial-veto authority to eliminate language in the budget that ordered the Wisconsin Department of Revenue to immediately update tax withholding tables.

“This is the strangest thing I’ve ever seen. I have no idea why he did that,” said John Witte, a University of Wisconsin-Madison professor emeritus who specializes in tax and budget policy.

Withholding tables are used to estimate the amount of income tax a worker can expect to owe to the state. According to a paper prepared by the Legislative Fiscal Bureau: “The individual income tax withholding tables were last adjusted on April 1, 2014. As such, the tables currently in effect are based on the tax rate and bracket structure that applied to tax year 2014.”

Wisconsin’s income taxes have been cut multiple times since 2014, and the 2021 changes reduced rates in the third bracket from 6.27% to 5.3%, which is projected to save taxpayers $2.36 billion over the next two years. The third bracket applies to wages between $23,930 and $263,480 for individuals, meaning most of the tax savings will go toward wealthier earners.

The effect of not updating the withholding tables means people are paying in more in taxes than they need to, but they get that money back when they file their income tax return. The Legislative Fiscal Bureau’s analysis provided a detailed example of what that would look like.

For a single individual with $24,000 of taxable income in tax year 2021, all of their income would be taxed within the first two income tax brackets under current law. However, under the current withholding tables, a portion of this same individual’s income would be subject to income tax withholding under the third income tax bracket. Moreover, the income tax rates associated with the bottom two brackets are higher under the withholding tables (4.0% and 5.84%) than the rates under current law (3.54% and 4.65%). In general, because state withholding is based on the individual income tax provisions in effect for tax year 2014, the tax amounts that are withheld are larger than if withholding were based on current law provisions.

In his veto message, Evers indicated he wants to hold on to that money in case the state needs to spend it elsewhere.

“I object to requiring the Department of Revenue to make these withholding table adjustments at a cost of approximately $700 million while other critical priorities have not been sufficiently funded by the Legislature. This veto does not increase anyone’s tax liability compared to what the Legislature passed,” wrote Evers.

When income taxes are withheld throughout the year and paid to the state, that money is used to fund general operations. A spokesperson for the Department of Administration confirmed the state does earn interest on that money, but said the interest rate is “extremely low” at 0.045%. However, the state doesn’t expect to earn any interest, as Evers wants the Legislature to spend the money.

“As noted in the governor’s veto message, the governor’s goal in vetoing the budget stabilization fund transfer and withholding table change is for the general fund balance to be invested into public schools, higher education, economic recovery and other priorities, and interest would not be earned on those expended funds,” said the spokesperson.

The Legislative Fiscal Bureau analysis also indicated a cost to changing withholding tables: “The main drawback of adjusting the withholding tables is the significant one-time cost to the state’s general fund. It should be noted that, absent other tax law changes, this one-time cost will continue to increase each year that the tables are not adjusted.”

Witte said there is speculation that Evers vetoed the change in the withholding tables because the governor hopes Democrats will take control of the Legislature in the 2022 election and repeal the tax cuts. By not changing the withholding tables, most taxpayers wouldn’t notice a difference, that thinking goes.

“If he changed the tables the tax cuts would be permanent,” said Witte.

“I can definitely squash that,” said Peter Barca, Secretary of the Department of Revenue. “The governor has no intention of reversing these tax cuts.”

Barca said it wasn’t a surprise to him Evers vetoed the provision.

“Virtually any governor would have vetoed that. We already have the authority to do it (change the withholding tables),” said Barca.

The Legislative Fiscal Bureau wrote what state law compels: “The Department (of Revenue) is required ‘from time to time’ to adjust these withholding tables to reflect any statutory changes to individual income tax rates and brackets.”

The seven years since the last update show “from time to time” is flexible wording.

Barca said Evers’ objection had more to do with the Legislature’s deadline of October 1 for making the changes. He said it’s common for governors to veto timelines from the Legislature.

“Don’t tell us what to do and when to do it,” said Barca.

Barca expects the Department of Revenue to adjust tax withholding tables over the course of the next year.

“We’re reviewing it, people get the (tax) break no matter when we do it,” he said.

According to Barca, a median income family of four with a household income of around $110,000 in 2021 will see a $683 tax decrease due to the tax cuts. Adjusting the withholding tables would bring them an extra $57 a month in take-home pay.

Workers can change their tax withholding anytime they choose by adjusting their W-4 statement, increasing or decreasing their tax withholding as needed. Barca noted most employees prefer to overpay and get a tax refund, as opposed to underpay and owe money at tax time.

“Just generally if you’re going to get $100 back versus owe $100, people would rather get the $100 back,” he said.

Witte agreed with that sentiment, even if he thinks it’s a bad idea.

“It’s stupid to pay more taxes and get it back at the end,” he said. “It’s the wrong strategy, but the vast majority of people in the United States do that and count on those refunds to do big purchases.”

Editor’s note: This article was updated with additional comment from the Wisconsin Department of Administration.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us