What Foxconn Means For The Great Lakes Compact

As Taiwanese electronics giant Foxconn touts its plans to build an LCD factory in southeastern Wisconsin, one open question is what demand that operation will place on Lake Michigan.

August 3, 2017

LCD screens and Lake Michigan sunrise illustration

At the turn of the century, a Canadian company named Nova Group sparked outrage across the Great Lakes region when it proposed to withdraw millions of gallons water from Lake Superior water and sell it in Asia. In the short term, this led Canada to crack down on freshwater exports. Over the long run, proposals like this and a long-brewing fear of outsiders coveting Great Lakes water helped to motivate the 2008 ratification of the Great Lakes Compact.

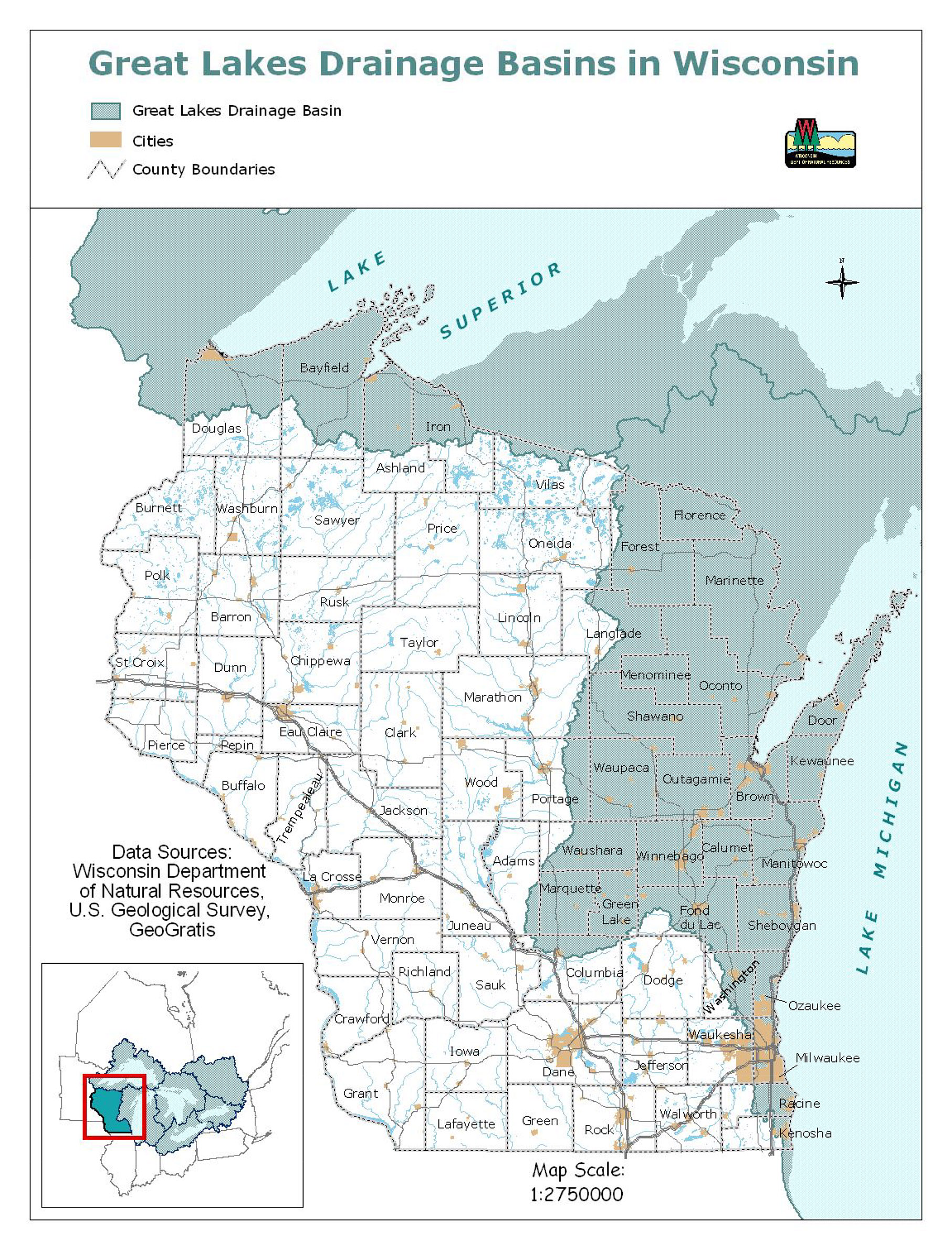

An agreement between eight U.S. states, the Great Lakes Compact regulates access to using the lakes’ water resources, which contain about one-fifth of the surface freshwater on earth. Only communities within the Great Lakes Basin — the region in which water drains into the lakes ecosystem as opposed to other watersheds like the Mississippi River’s — may use these resources on a standard basis. Water utilities completely outside the basin must receive multi-state approval via the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Council.

As vast areas in North America and around the world grapple with water scarcity, elected officials and business boosters anticipate that resource insecurity will lead more companies to set up shop in the Great Lakes region. One very water-intensive business is electronics manufacturing. As Taiwanese electronics giant Foxconn touts its plans to build an LCD factory in southeastern Wisconsin, one open question is what demand that operation will place on Lake Michigan.

LCD screens: a thirsty product

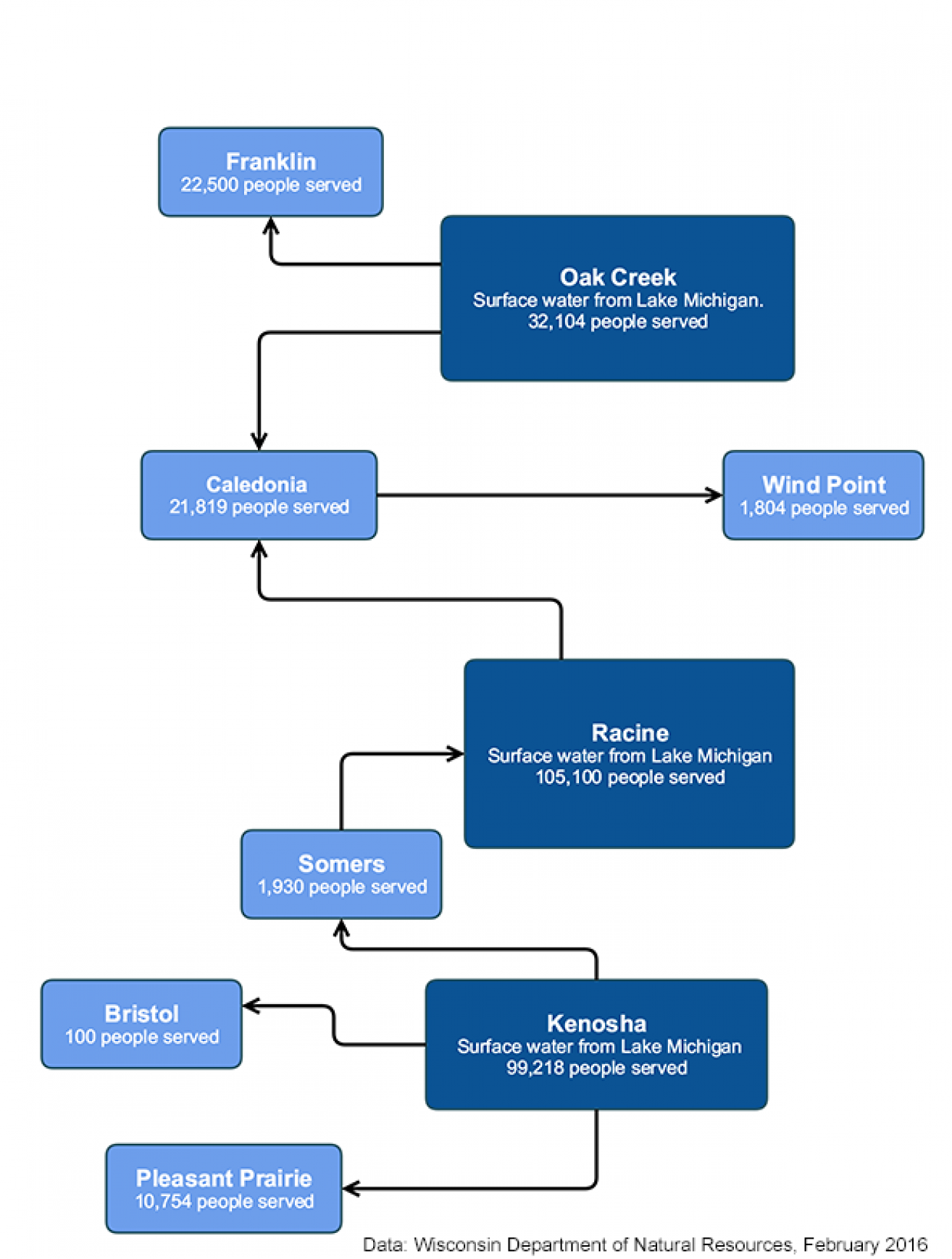

David Hsieh, a Taipei-based analyst and displays expert with the financial intelligence firm IHS Markit, recently noted that such an operation could use as much as 60,000 cubic meters of water per day. That volume equals 15,850,200 gallons, which is nearly as much as the entire city of Racine uses in a day.

An LCD, or liquid-crystal display, consists of sandwiched layers of glass substrate, liquid crystals, and optical filters and reflectors. These layers, Hsieh said, are the key to why fabricating these screens requires so much water. Throughout the manufacturing process, the layers must be cleaned over and over again for the end product to function correctly.

“It needs the purity of the glass surface so that the semiconductor layer can be perfectly exposed onto the panel surface,” Hsieh said in an email. He noted that some of the water used in these processes can be recycled.

Some of these steps in electronics manufacturing use a highly purified type of water called ultra-pure water. In the process of converting municipal water supplies into this form, some water cannot be returned to the ecosystem. That means that an LCD fabrication facility like the proposed Foxconn factory would not be able to return all the water it uses to Lake Michigan or other sources, even if it goes through proper wastewater treatment processes. Environmental regulators call this problem “consumptive use.”

The boundaries around Great Lakes water

The Great Lakes Compact sets a variety of conditions on how entities not located within the watershed can access the lakes’ water. How these rules applies to Foxconn will depend very specifically on where its factory complex is located. If plans of a site in Racine or Kenosha counties pan out, three distinct scenarios would trigger different rules under the compact: The facility will be entirely within the Great Lakes Basin, in a municipality that straddles the basin border, or in a county that straddles the border but not within a municipality that straddles it.

If a water user is located fully within the Great Lakes Basin, it can access the water with state approval. If the user is in a straddling municipality and creates a new or increased consumptive use of water over a 5 million gallon per day threshold, that would also require regional U.S. governors and Canadian provincial premiers to review the water use and issue non-binding guidance, said Pete Johnson, deputy director of the Conference of Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Governors and Premiers. Johnson helped draft the Great Lakes Compact, and the conference is the organization in charge of administering its rules.

The third scenario is a bit more complex. If the Foxconn factory is built in a municipality fully outside the Great Lakes Basin but still in a county that straddles the basin line — say, somewhere in south-central Racine County — that’s considered a “diversion” of water outside the basin, and would require the unanimous approval from the governors of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. (The Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quu00e9bec have a role in non-binding reviews of water use plans in the Great Lakes, but are not technically parties to the Great Lakes Compact.) This last scenario is essentially the process the city of Waukesha went through in its long-fought and ultimately successful bid to tap Lake Michigan. Waukesha was the first city outside the basin but in a straddling county to seek and receive access to the water under the compact.

Once it’s actually sourcing water from Lake Michigan in 2023, Waukesha plans to use about 8.2 million gallons per day. Foxconn is hoping to have its factory up and running by 2020. The company hasn’t indicated anything about how much water it would use, but a large-scale factory will require millions of gallons of water a day, not just for employee needs, but more importantly for the water-intensive LCD manufacturing process.

Waukesha spent years just seeking permission to access Lake Michigan water, albeit with support from state officials, including Gov. Scott Walker. Foxconn wants its facility to be operational by 2020. Meanwhile, Walker and state legislators want to give the company a pass on broad swaths of state environmental regulations. This aspect of the state’s incentives package for Foxconn wouldn’t exempt the company from complying with federal regulations (some of which the state is tasked with enforcing through its agencies, including the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources) or with the terms of the Great Lakes Compact.

What Wisconsin can and can’t change

Debate over the incentives bill Wisconsin legislators and Walker have put forward for Foxconn has muddied the waters over how the Great Lakes Compact would apply to the planned factory.

An Aug. 1, 2017 op-ed by state Sen. Kathleen Vinehout, D-Alma, a possible 2018 gubernatorial candidate in Wisconsin, stated “[t]he bill changes the law related to diversion of water under the Great Lakes Compact.” However, the compact is an agreement among eight U.S. states, which means that no single state can unilaterally change its terms. That said, states do have discretion as to how they go about complying with the compact in certain situations.

According to an analysis from Wisconsin’s nonpartisan Legislative Fiscal Bureau, the incentives bill would loosen the state’s permitting requirements for water access if the facility were located within a straddling community — again, a city, village or town that is partially in and partially out of the Great Lakes Basin.

Foxconn would be exempt from having to submit to the DNR a “water supply service area plan” that spells out how the facility would go about using water supplies and the projected economic and environmental impacts. This exemption would be a considerable change in how Wisconsin holds up its part of the bargain under the Great Lakes Compact, but does not alter the compact itself. The bill changes nothing about what would happen if the factory were in a straddling county without being in a straddling community— because it can’t.

“Our understanding is that as long as it’s not changing the basic terms of the compact, the basic principles, then the state has some leeway as to how it’s implemented,” said Paul Ferguson, program director for natural resources at the LFB. However, he added that the Foxconn facility would still have to return as much water as it uses to the Great Lakes Basin, or close to it. If it operates for a 90-day period in which it uses an average of 5 million gallons per day more than it returns, Ferguson said, that would trigger a review from the compact council.

Reached for clarification, a member of Vinehout’s staff referred questions to Ferguson.

Pete Johnson of Conference of Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Governors and Premiers would not comment specifically on the Foxconn deal, but drew a distinction between what an individual state can and cannot do under the Great Lakes Compact.

“The general rule of compacts is that they’re a contract between states and you can’t change the terms of the compact,” he said. “However, when the terms of the compact were passed, eachof the states adopted implementing legislation on how the terms of the compact would be implemented within each jurisdiction.”

Questions of location and lax regulation

Speculating about where the proposed Foxconn factory complex might end up in relation to the Great Lakes Basin gets messy fast. The basin’s border follows a jagged path through southeastern Wisconsin, not neatly aligned with political borders or important pieces of infrastructure like highways and railroads. One area Foxconn may be eyeing in Racine County would put the facility just barely in or out of the basin depending on which specific parcels of land the company buys and builds on.

Foxconn may try to source its water via the city of Racine’s waterworks. This also parallels the experience of Waukesha, which plans to get its water via the Milwaukee suburb of Oak Creek, rather than tapping directly into Lake Michigan itself.

State and federal environmental regulations would treat a private facility like the one Foxconn proposes as a separate water utility unto itself, not simply a customer of a city water utility. In eastern Wisconsin, it’s fairly typical for smaller cities to purchase water from bigger ones that already have water intake and treatment infrastructure in place.

Foxconn could also try to draw on groundwater wells in the vicinity of its facility. However, that would be no less controversial, said John Dickert, who previously served as the mayor of Racine and recently became president of the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative, a nonprofit that brings together dozens of U.S. and Canadian communities to advocate for protecting the region’s water resources. The GLSCI opposed Waukesha’s bid for Lake Michigan water, as did Dickert in his capacity as Racine’s mayor.

Dickert said he’s been hearing the Foxconn facility would use about 10 million gallons of water per day, lower than the 15.8 million estimated by financial analyst David Hsieh, but still a significant volume and more than Waukesha plans to draw. Sourcing any amount like that from groundwater would likely put Foxconn at odds with nearby farmers and communities, and contribute to drawdown on nearby lakes, rivers, and streams.

“I don’t think you’d have a lot of people in those areas that would be excited about them pulling 10 million gallons a day out of a high-capacity aquifer,” Dickert said.

Dickert and other opponents of the Waukesha water diversion have said publicly that they believe the approval of that city’s bid set a bad precedent for future applications of the Great Lake Compact. Both Dickert and Pete Johnson of the Conference of Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Governors declined to speculate on how that precedent might play out for Foxconn, because so few details have come out about the project.

What Dickert and his organization do believe, though, is that more companies will try to establish a foothold in the Midwest in order to take advantage of the Great Lakes’ water resources.

“If you’re pulling it out of the lake, you know you have a significant resource that is sustainable,” he said.

Foxconn considered building facilities in Michigan before going with Wisconsin.

Hsieh also said that he anticipates electronics manufacturers will continue to be drawn to the Great Lakes region in the future.

If this industry clustering does indeed become a major trend, Dickert wants to see state and federal environmental regulations upheld, along with Great Lakes Compact provisions that govern access to water. He called it “incredibly irresponsible” to carve out special environmental exemptions for Foxconn.

In other words, an agreement initially designed to prevent shipping water out of the Great Lakes to places like like Asia might be tested by foreign companies.

“If you do this for Foxconn, the next company that’s going to come in is going to ask for the same thing,” Dickert said.

Editor’s note: This article was updated to clarify the terms of the Great Lake Compact, and corrected to note that projected water use by an electronics manufacturing facility could reach 60,000 cubic meters per day.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us