The Great Migration And Beloit's African American Heritage

Beloit stands out in Wisconsin. It's a small city — home to fewer than 40,000 people — with a relatively large African American community.

By Will Cushman

February 13, 2020

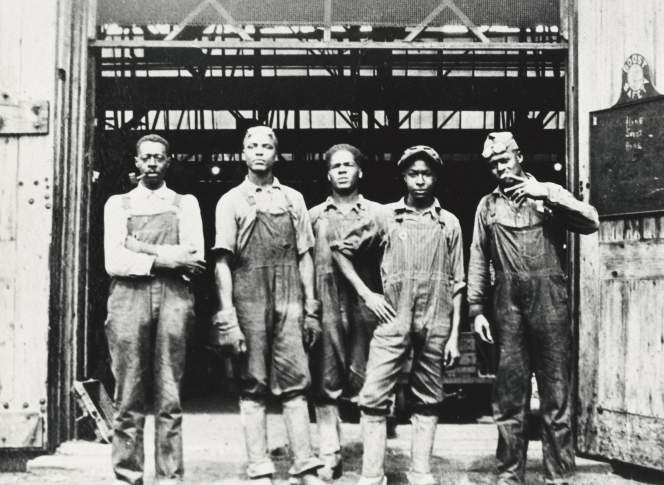

African American foundry workers at Fairbanks, Morse and Company in 1925

Perched along the state’s border with Illinois, Beloit is as far south as one can get in Wisconsin. However, the city’s roots extend much farther into the South, where they tap into the fertile soils of northeast Mississippi and a handful of small agricultural towns.

Beloit stands out in Wisconsin. It’s a small city — home to fewer than 40,000 people — with a relatively large African American community. Black residents have called Beloit home since its early years in the mid 19th century — one of the city’s first blacksmiths was an African American man. But the city’s black community remained tiny in its early years, numbering in the dozens until the second decade of the 20th century.

African Americans began arriving in Beloit by the hundreds in the 1910s as part of the first Great Migration, which continued for several decades up to World War II. Millions of black Southerners moved north to find employment and to escape rampant racial violence and state-sanctioned segregation. In the Midwest, major cities like Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit and Milwaukee became prominent Great Migration destinations. But despite being lesser-known, some smaller communities also attracted African American migrants from the South.

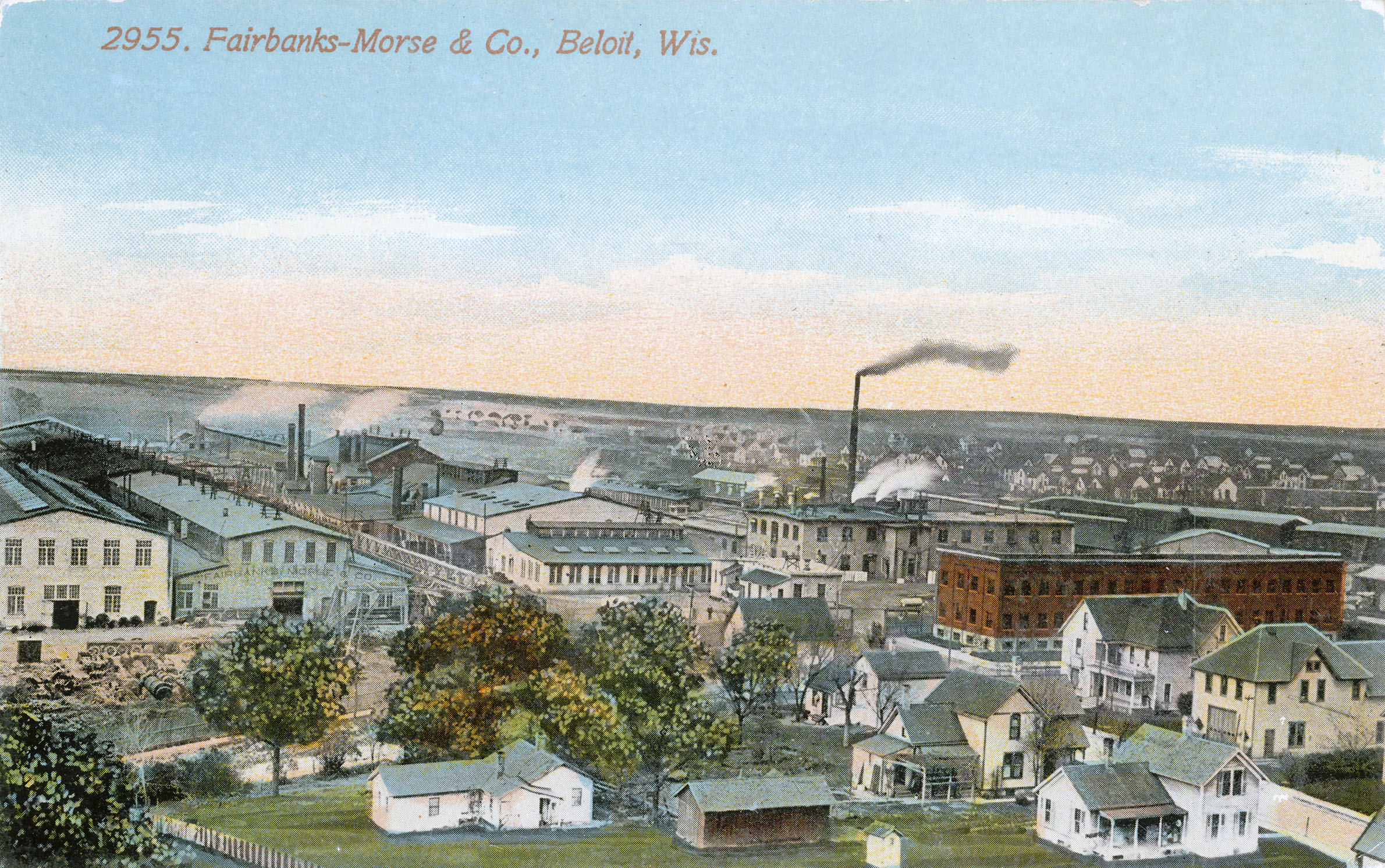

It was Beloit’s manufacturing sector that attracted and benefited from the new workforce. Specifically, the Beloit Iron Works foundry and a manufacturer of pumps, engines and other products known as Fairbanks, Morse and Company drew hundreds of young men and their families north. In just a decade or so, Beloit’s African American community numbered greater than 2,000, upward of a tenth of the city’s total population. (Beloit is about 15% African American in 2020.) Many of these newcomers came from four small communities in northeast Mississippi’s agricultural belt: Pontotoc, Houston, New Albany and West Point.

In Beloit’s factories, African Americans found new opportunities, but they also encountered familiar racism.

“They were still getting overlooked to become superintendents, foremans and all those things,” said Linda Fair, an academic advisor at Blackhawk Technical College in Janesville. Fair recounted Beloit’s black history in a talk at the Beloit Public Library recorded for a June 25, 2019 episode of PBS Wisconsin’s University Place.

In addition to workplace discrimination, Fair described the structural and cultural barriers African Americans encountered in Beloit, including housing segregation, health care discrimination and a lack of employment opportunities outside of low-wage manufacturing and domestic work. But Beloit’s black residents persevered, Fair said, leaning on their religious faith and pursuing education as a means to greater opportunities.

Such opportunities expanded in the second half of the 20th century, as a national civil rights movement precipitated landmark legislation like the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited educational, employment and public services discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin.

The legislation and changing attitudes opened up new opportunities for Beloit’s African American community, and Fair named a number of community members who were the first among their peers to land positions in city government, local schools and Beloit’s health care system.

“At the time when they were doing these things, they weren’t doing it so that I could stand here in 2019 and shout their names out,” said Fair. “They did it because it was in their heart, it was in their mind, it was embedded into them to reach out, do what you gotta do, take care of your family and help leave a legacy for some others to follow.”

Key facts

- Beloit’s first black residents were Mr. and Mrs. Emmanuel Craig, who settled in the village in 1839, soon after its founding. Emmanuel Craig was employed as a coachman.

- The Ousleys were one of Beloit’s first black families, arriving decades before the first Great Migration. Grace Ousley was the first African American to graduate from Beloit High School and the first black woman to graduate from Beloit College, in 1904.

- The city’s black population was tiny up through the second decade of the 20th century, when thousands of African Americans moved to Beloit. Most of these newcomers to Beloit came from four small cities in northeast Mississippi during the first wave of the Great Migration.

- Only two financial institutions in Beloit would loan money to African Americans in the early portion of the 20th century, and much of the local real estate was restricted to white residents only.

- Beloit’s Fairbanks Flats apartments, which remain in existence in 2020, were originally built in the early 20th century to house an influx of workers at Fairbanks, Morse and Company, many of whom were African Americans from the South.

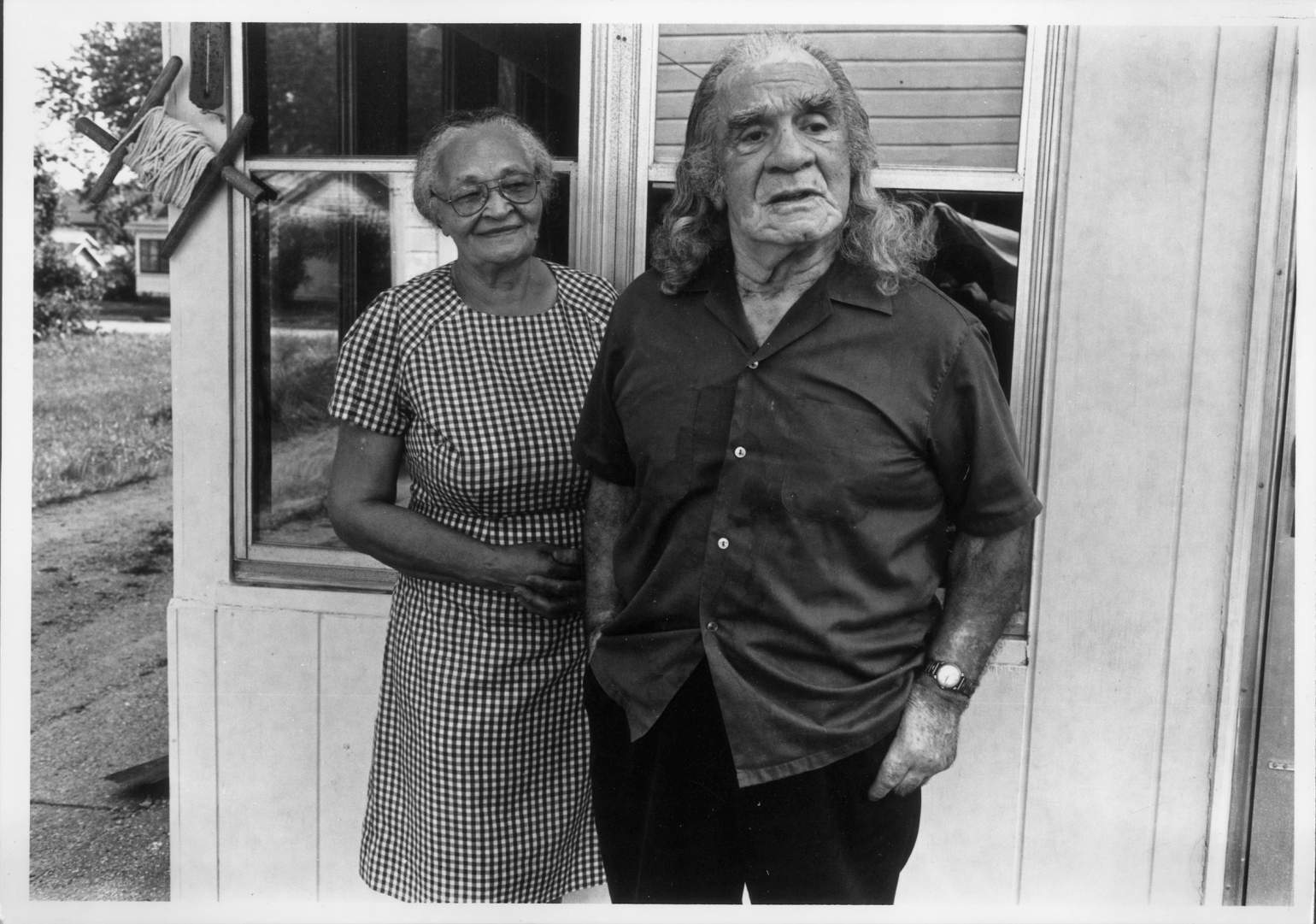

- Among the thousands of migrants who came to Beloit from Mississippi during the 1910s was Rubie White (later Rubie Bond), who arrived as a girl with her family in 1917. She shared her story in PBS Wisconsin’s Wisconsin Stories: Finding a Home program in 1998.

Key quotes

- On the importance of Beloit’s proximity to Chicago in attracting newcomers during the Great Migration: “Beloit was situated in an ideal location on the border of Illinois and Wisconsin, so they could still … reach their family members that might be in Chicago.”

- On the outsize role of Fairbanks-Morse in attracting African American workers: “‘Beloit, Beloit, Beloit,’ said the train conductor as he carried loads of people from the South to the North to work at Fairbanks-Morse. He called out again, ‘Beloit, Beloit, Beloit.’ No one moved. Then he said, ‘Fairbanks,’ and the whole train emptied.”

- On systematic housing discrimination black residents faced: “Realtors and financial institutions would not rent, sell or finance property to Blacks unless there were already Blacks living in that area.”

- On the historical importance of religious faith within Beloit’s black communities: “Church has served as a religious and social center. Especially think about all the people that transported north from Houston, Pontotoc, some of those cities — they didn’t really know much about the area, so their hangout was the church. They had Bible meetings. You had choir rehearsals. It was just their social gathering place. They relied heavily on their religious beliefs.”

- On the value of understanding your community’s history: “Now, we must never forget, sometimes it is impossible to know where you are headed without reflecting on where you came from. Understanding your heritage, your roots and your ancestry is an important part of carving out your future.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us