The businessman: Pig farm developer gains little trust in Wisconsin town, but he doesn't particularly care

Critics accuse a developer of disregarding local concerns in his push to construct the state's largest pig farm in rural Burnett County, but he calls himself the victim of "selfish" residents.

Wisconsin Watch

December 20, 2023 • Northern Region

For nearly five years, residents and property owners in the northwest Wisconsin town of Trade Lake have clashed with a developer of a proposed $20 million pig farm. The swine breeding operation, known as Cumberland LLC, would be the state's largest. Locals have found little comfort in answers to their questions about how the farm would impact their quality of life. (Credit: Andrew Mulhearn for Wisconsin Watch)

This article was first published by Wisconsin Watch. It is the second story in a three-part series called Hogtied, which examines the political, regulatory and economic forces shaping a proposal to build the state’s largest pig farm.

He says he’s an open book.

He calls himself a creator.

“Not a details person at all!” his LinkedIn profile declares. “The best compliments to me is working around detailed people. I create a project and need them to complete it.”

Jeff Sauer travels the country, bringing tidings of pigs.

In January 2019, Sauer came to Trade Lake, Wisconsin, with a plan in his pocket. He sought to establish the region’s first large swine breeding farm, also known as a concentrated animal feeding operation, or CAFO. For that, he required farmland and lots of it.

The $20 million project, known as Cumberland LLC, could have housed more than 26,000 hogs — the state’s biggest sow operation. Given the potential of the massive farm to transform life in Burnett County, residents and property owners raised a gauntlet of questions: Who would own and operate the facility? Would it be well run? Who could the community hold accountable if it wasn’t?

They found little comfort in the answers.

Opponents discovered Cumberland’s owners sought to purchase fields from Trade Lake’s then chairman, Jim Melin. Several sued to remove Melin from office, accusing the local official of conflicts of interest. From testimony collected during litigation, the plaintiffs believed they could establish Sauer falsely represented himself as a company owner when he submitted a CAFO application. They urged the state to reject it.

Sauer, who has since accumulated infractions in business dealings in another Wisconsin community, has sown distrust in Trade Lake among a public already wary of large livestock farming. Critics accused him of trying to site the swine facility, sentiment be damned.

Opponents have asked whether the level of diligence the company has invested into the hog farm’s planning and community relations foreshadows a lack of care and transparency in operations. Adding to their unease is state regulators’ reliance upon self-monitoring and community watchdogging to safeguard the environment from agricultural pollution.

Meanwhile, Cumberland’s absentee owners hold minimal culpability in the event of damage because they formed a limited liability company that would own the facility — a common industry practice.

Sauer rejected the accusations and maintains he has never lied. In fact, Sauer said, he now is the sole owner of the entire project.

That the facility would be run poorly is preposterous, he said. “What would make you think that we would put an investment of that magnitude in and then make it look like trash?” Sauer told Wisconsin Watch.

He considers himself, and others in the local agriculture community, the victims of “selfish” and “stupid” “crazies” and a hostile press.

“I bet you any money that your publication that you’re wanting to write right here for this story is to slam me one more time — to slam Cumberland LLC,” Sauer said. “Have you heard one uplifting story about this whole thing since it began?”

Searching for a farmer’s sympathy

Cumberland’s developers anticipated controversy from the start, particularly over potential odor and pollution. They chalked it up to community resistance to change.

Sauer filed a preliminary CAFO application with the state in early 2019 after scoping out properties in the Trade Lake area for months.

“The key to our puzzle is a participating farmer,” he later explained.

Sauer identified one in Erik Melin, 38, Jim Melin’s son. Erik, who was taking over his family’s farming business, would purchase manure from Cumberland to fertilize fields he owns and rents.

In April 2019, a reporter from the area’s newspaper, the Inter-County Leader, learned of the proposal and contacted Erik for an interview. Erik texted Sauer shortly after and suggested Sauer do the talking.

“We may want to wait on this opportunity for a while,” Sauer responded, asking Erik to hold off until he could coach him. “Media can distort what you are implying and we don’t want that.”

Sauer had reason to believe waiting to comment was for the best. Public sentiment toward CAFOs usually sours, he said.

“It always does.”

Jeff Sauer speaks in a 2019 interview with “Here & Now.” He arrived in Trade Lake in 2019 with a plan to establish Wisconsin’s largest pig farm. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Trade Lake meets the businessman

Sauer unveiled his vision to Trade Lake community members the previous January at a town board meeting, but his presentation was listed under a vague agenda heading, and few members of the public appeared.

Still, word spread.

The board revisited the matter at Trade Lake’s annual meeting in April. The Inter-County Leader had outlined details of the Melin sale the previous day, and more than 120 people overflowed the historic town hall for a monthly meeting that normally draws just a handful or two.

Property owners sought answers from Sauer in the form of scientific data, contingency plans and financial assurances.

They got something else.

“I’d like to know who he is,” said Trade Lake resident Howard Pahl, 71, at the meeting’s start.

“Well, I’ve been in a lot of post offices under wanted posters,” Sauer opened.

The crowd raucously laughed.

Sauer introduced himself as a farmer from Thorp, Wisconsin, and a part-owner of a dairy and hog operation, unrelated to Cumberland.

He marketed the proposed swine farm’s advantages for Trade Lake: It would source its corn locally, create about two dozen new jobs and annually generate $5 million in economic activity.

“Can I interrupt you for a second?” said local resident Dean Moody. “You’re not telling us who you are.”

In 1966 Sauer moved with his five siblings to Thorp, where their father, Arthur, farmed more than 1,000 acres for 30 years. Sauer says he concluded his formal education with the eighth grade, then attended the school of “hard knocks” to learn construction.

Now 57, he is married, by his account, to a woman who doesn’t like hogs. In August 2019, Sauer was a father of seven, who ranged in age from 9 to 35.

He knows how to apply pesticides and herbicides. The co-owner of the veterinary company with whom Sauer planned Cumberland describes him as a “very, very clever guy” in construction and building equipment.

Sauer also is entrepreneurial. After working as a sales manager at Thorp Equipment, where he helped design calf nurseries, Sauer in 2017 founded Clear-View Solutions Group, which assists swine producers with permitting in Wisconsin.

His ventures have landed him into conflict with the state and a central Wisconsin town where he operates an animal composting and rendering business.

Sauer says the company, Organic Waste Connections, which disposes of cow, horse, goat, llama, sheep and pig carcasses, is rooted in core values “like a foundation built on treating others as Jesus instructed us to — by showing respect for them and their needs.”

A sign noting its 1890 construction stands in front of the Trade Lake Town Hall in Burnett County, on April 28, 2023. (Credit: Drake White-Bergey / Wisconsin Watch)

Developer faces environmental lawsuits and citations

In November 2022, the town of Reseburg sued Sauer, alleging he is operating the facility without a license, generating noxious odors, producing leachate and discharging stormwater with dangerous levels of E. coli that drains into nearby waterways.

The lawsuit, which claims Sauer began commercial operations in June 2020, alleges that he refused to abide by a town animal composting and rendering ordinance and cooperate with local officials.

Denying all of the town’s allegations, Sauer maintained he started the business in 2008, a year before the town unlawfully enacted its “retaliatory” ordinance, which has since, he asserted, only been applied to him, illegally.

In August, the parties agreed to parameters, effective through January 2024, concerning the disposal and storage of dead animals.

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources also cited Sauer three times. A since-dismissed case from 2022 alleged Sauer failed to amend an industrial stormwater pollution prevention plan. The following September, after repeated warnings, Sauer was cited for failing to obtain a construction site stormwater discharge permit and to develop an erosion control plan.

In September, Sauer pleaded no contest in Clark County Circuit Court to one of the charges, and the state dismissed the other. He was fined $5,000.

“He has painted himself in a very unflattering light, and I suspect we will hear refrains of, ‘How come DNR would consider granting him a permit for a complex operation like a CAFO when he can’t even get into compliance with a stormwater permit?'” wrote an agency staff member to the state’s CAFO permit coordinator.

Sauer, who said the novelty of Organic Waste Connections is bound to ruffle feathers and “has no correlation to the Cumberland LLC project,” told Wisconsin Watch that it’s up to the state’s agricultural and natural resources departments to regulate his business with respect to the offenses named in the town’s lawsuit — not Reseburg.

“So if we’re in good standing with those two departments,” he said, “the other stuff is just basically bullshit.”

Rain soaks the ground at the site of a proposed concentrated animal feeding operation, or CAFO, in the Burnett County town of Trade Lake, on April 28, 2023. (Credit: Drake White-Bergey / Wisconsin Watch)

Developer on defense as community crackles

At the Trade Lake annual meeting, attendees lobbed a volley of concerns Sauer’s way.

What would Cumberland do for the community if the farm impaired local air or water?

“So the question ‘if’ is a really big word ’cause you’re assuming it will and I’m assuming it won’t,” Sauer said, adding, “You cannot deal with something of the unknown, because of the unknown, with the unknown.”

A local farmer asked what guarantees the company could provide that it would “properly” respond to accidents like manure spills.

“The answer to your question is there’s only two guarantees in life,” Sauer said. “Death and taxes.”

The crowd fumed.

“I can guarantee you that it ain’t going to smell, right?” Sauer shouted over the grumbling. “And I can leave here and fall off the end of the road and get killed. So what good is it?”

“You’re asking us to assume a lot of risk and trust,” another attendee said. “And I just ain’t feelin’ the love.”

A woman asked if a “comprehensive and tangible” impact study would be available.

“This is our heritage,” she said. “This is our legacy. This is our birthright. It isn’t yours. And you’re trying to dictate to us. And I’m mad as all get-out.”

The room burst into applause and amens.

“So, that is not required for us to do at the moment,” Sauer said.

He reminded the audience he didn’t have to publicly discuss the hog farm until the state held a public hearing later in the review process.

“You’re working from historical knowledge,” he said. “Some of these things are fallacies.”

Sauer might have attempted to persuade the crowd that draining the local aquifer doesn’t make financial sense for Cumberland’s owners or that the manure wouldn’t smell because it would be treated and injected into the ground.

But, he said in subsequent interviews, what’s the point of trying to convince the “antis” when community members already decided they don’t want the pig farm?

Controversy has existed “since the beginning of time,” Sauer told the crowd.

Trade Lake experienced controversy over a dock, he continued, referring to another divisive town issue. Controversy over boat wakes too.

“And quite honestly, everybody’s talking about negatives here,” Sauer said. “I want to know would your battery work in your car if you had it all negatives? No, it’s an equilibrium of positives and negatives which makes your economy work.”

At the urging of another attendee, Erik Melin addressed the gathering to share his enthusiasm.

“I’m very excited for this,” he said. “It allows for me and my wife and my children to be profitable in farming. We are very invested in this community. We love Trade Lake. We don’t want to ruin it for anybody.”

When residents suggested passing a CAFO moratorium, Sauer told them they couldn’t do so that night, and even if they did, Cumberland would be exempt because he already submitted the application to the state.

“Wisconsin sets all the criteria,” Sauer said. “You follow the rules, you do exactly as laid out, you get the permit. It’s not ‘if.'”

By the end of the meeting, he was hurling legal threats.

“Correct me if I’m wrong,” Moody said, “but what I heard you say is you’re coming in whether you have to do it with the lawyers or we welcome you.”

“I won’t even pay a penny for that litigation,” Sauer said, in reference to the moratorium. “The state of Wisconsin will fight this, and that’s not going to cost me a penny, but it’s going to cost taxpayers.”

Sauer contended that even if all locals don’t benefit from the hog farm directly, the Melins’ opportunity would extend to the public.

“You got manufacturing in town here. Do you prosper from that? No, but it does make the community,” Sauer said. “So it’s every aspect is a building components of everything that’s in sync that makes the community stronger.”

“Can I stop you, ’cause you’ve gotten so far from my statement,” Moody said.

“No!” Sauer said.

“Yeah, you have —”

“The reality is that our intentions are to come.”

“Yeah, any way you have to.”

During a deposition that occurred in the Melin lawsuit, Sauer said he left the annual meeting with the impression that there were “a bunch of pricks” in Trade Lake.

“You guys are all selfish,” he told trial lawyer Andy Marshall. “You’re included.”

Marshall, a town property owner who represented the 11 plaintiffs who sued Melin, asked Sauer if residents’ concerns over groundwater contamination or disease are also selfish.

“Fake news,” Sauer said.

Trial lawyer Andy Marshall stands on his property in the town of Trade Lake., in Burnett County on April 30, 2023. Marshall represented residents in a lawsuit that accused Trade Lake Town Board Chairman Jim Melin of alleged conflicts of interest in the construction of the state’s largest pig farm. (Credit: Drake White-Bergey / Wisconsin Watch)

Trade Lake moves to halt hog farm

Following the annual meeting, the community’s opposition to Cumberland was “swift and overwhelming,” as Marshall, 63, described it.

Several Trade Lake property owners and residents formed a local opposition group, KnowCAFOs, and periodically deluged the email inboxes of Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency staff, along with elected and appointed officials. The St. Croix Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin also admonished the project.

Opponents questioned the surveying and study of the farm site and unsuccessfully petitioned regulators to conduct an environmental impact statement.

“We will not back down until the DNR starts to protect the waters of our state as the department was intended,” wrote Trade Lake resident Judi Clarin, 62.

Confusion over CAFO ownership

Sauer has been described as the consultant, coordinator or middleman, but questions remained about whether he co-owned or managed Cumberland — which formed in 2018 — at the time he submitted his initial CAFO application.

People who file with the state must certify they are one or the other, but many Trade Lake property owners alleged Sauer misrepresented himself, a violation punishable by a fine of up to $10,000 or six months imprisonment. Opponents cited the purported falsification as grounds for denying Cumberland’s application.

Sauer was retained by owners of an Algona, Iowa, swine management and veterinary company, Suidae Health and Production, in 2017 to site and build the Trade Lake farm. Sauer said he wouldn’t be paid until he did so. In 2020, at least six of Cumberland’s owners were current or former Suidae veterinarians.

As he was deposed in 2019, Sauer at various points claimed not to be an owner or know who the owners are; to never have been an owner; to be unsure whether he is an owner; to not recall whether Cumberland’s other owners ever told him that he, too, is an owner; and that it’s possible that he might be an owner because he might be named so in the future.

When confronted with these contradictions, Sauer said he, in fact, is actually the operator and manager.

“Operator and manager of what?” Marshall asked.

“This piece of paper,” Sauer said, referring to the CAFO application, later adding, “This piece of property. This whole facility until it’s up and running.”

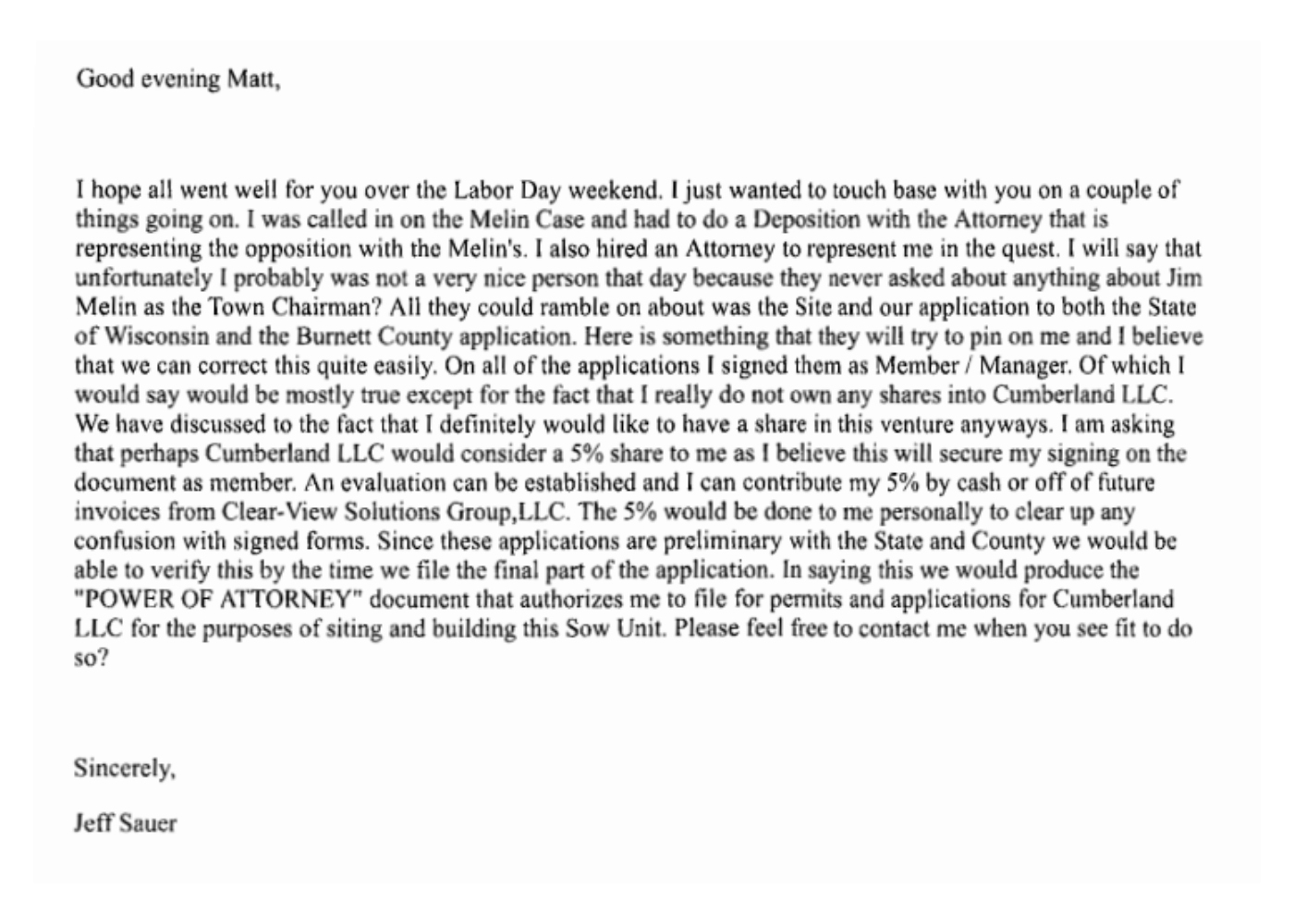

Four days after Sauer’s deposition, he contacted Suidae veterinarian and Cumberland co-owner Dr. Matt Anderson.

“On all of the applications, I signed them as Member/Manager,” Sauer told Anderson. “Of which I would say would be mostly true except for the fact that I really do not own any shares into Cumberland LLC.”

Sauer suggested that Cumberland give him a 5% cut of the company, which would prove he was an owner. Opponents took Sauer’s message as evidence that he understood he’d been “caught” and sought to “cover up the false statements” he made on the application. Afterward, the Department of Natural Resources required Sauer to verify he was authorized to sign it.

Further convoluting Cumberland’s ownership were Anderson’s remarks at a Burnett County Natural Resources Board hearing in July 2019, shortly before the committee recommended the county board of supervisors also enact a year-long CAFO moratorium.

“I’ve been an owner in Suidae for 20 years and I’ve been a veterinarian serving animals and those people that own animals for just over 20 years, and we’re not a CAFO,” Anderson told the audience. “We’re a service provider.”

“We sought” to go about the state’s permitting process “as best we can,” he continued, “not sneaking around in any way.” The hog farm, “if done responsibly, which would certainly be our intent,” presents “no danger to the community.”

Marshall, who also deposed Anderson, asked why Anderson failed to mention that he happens to be one of the CAFO’s owners.

“Mr. Marshall, we are open and honest people so we expect to be perceived that way,” said Anderson, who did not respond to Wisconsin Watch’s requests for comment.

“I’m wondering why, if you wanted to be open and honest, you don’t communicate to the county board that’s considering something with respect to the business that you own that you’re part owner of the business,” Marshall said. “That strikes me as being odd.”

As opponents of the proposed Cumberland LLC pig farm questioned his role in the project in 2019, Jeff Sauer emailed Suidae veterinarian and Cumberland co-owner Dr. Matt Anderson to request a 5% cut of the company, which would prove he was an owner of the proposed pig farm. This image shows an excerpt of Sauer’s Sept. 2, 2019, email to Anderson.

How CAFO partners limit liability

Many details of the Cumberland project are scant as the private company’s finances and operations plans are shielded from disclosure.

Under the original proposal, Cumberland would own the buildings, but not the hogs. Suidae Health and Production also would own no hogs, but its clientele would. Suidae, instead, would handle the farm’s management and payroll and receive payment for each pig that leaves the facility for finishing.

But Trade Lake community members took note that Cumberland’s absentee owners structured the business as a limited liability company.

Research conducted by University of Kentucky associate professor of sociology Loka Ashwood found that farm investors form LLCs to shield personal assets in case of business failure, enabling them to take on more financial risk. Instead, risk is thrust upon the communities in which CAFOs operate.

“They know they’ll have spills. They know they’ll have disease outbreaks. They know that is going to happen,” Ashwood said. “So they need to reduce their liability and culpability.”

One effective and typical system, Ashwood found, uses a chain of LLCs. One LLC can retain the land beneath a CAFO and lease it to a different LLC that owns the buildings. That LLC can, in turn, lease the buildings to the LLC that operates the business. The operating LLC may hold no assets, so in the event of a lawsuit due to poor management, that LLC can claim it lacks them.

Meanwhile, absentee investors don’t necessarily face community pressures to operate responsibly as a local farmer would.

It’s unclear to what degree Cumberland would operate under this model.

With respect to risk management, Sauer testified that Cumberland’s owners hadn’t considered putting up security bonds to resolve potential nuisance claims because they aren’t required to.

“They can pick up and they can move on when the moment is right for them, leaving us with what’s behind,” Ramona Moody, wife of Dean Moody and the current chair of the Trade Lake board, told PBS Wisconsin in 2019. “The cleanup, whatever they’ve left in their facilities, that ends up becoming our responsibility. So who holds them accountable?”

Trade Lake community members decided to do just that.

Ramona Moody speaks in a 2019 interview with “Here & Now.” She is the chair of the Trade Lake town board in 2023, and wonders about accountability when it comes to risks associated with CAFOs given ownership that can be structured to limit their liability. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Trade Lake enacts CAFO regulations

After Melin agreed to step down as town chair, the Trade Lake board passed a CAFO ordinance and moratorium.

The ordinance, since updated, does not impact the siting of large farms but regulates the way they run.

Trade Lake requires new CAFOs of 500 animal units or greater — 1,250 swine or 357 dairy cows — to apply for a permit that regulates waste management, animal health and mortality, water use and air pollution. Owners also must prove the farm won’t harm nearby property values or roadways. A financial assurance must be provided to cover application review and enforcement and, in the event of pollution or closure, cleanup costs.

“They call people ‘activists,'” Clarin said, “but they’re just people that are actively trying to protect their water.”

Unsurprisingly, some farmers bristled at the ordinance. To their disbelief, it limits farm vehicles and large trucks entering and exiting CAFO premises to standard business hours and days, except vehicles involved in planting, harvesting and haying, which can operate at any time.

“It’s pretty clear that they just don’t want farming at all,” Erik Melin said. “I don’t know where you would compromise.”

Developer on town’s concerns: ‘I don’t care’

Around the time Sauer asked Anderson for a 5% share in Cumberland, Marshall contacted Burnett County’s administrator to explain why the county should reject Cumberland’s local CAFO application.

One reason he cited: Sauer’s “contempt” for the county and residents of Trade Lake.

When he was deposed, Sauer testified that he consulted with members of Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce who told him that Burnett County’s CAFO moratorium, passed in July 2019, was illegal. The business lobbying organization, Wisconsin’s largest, has played an outsized role in opposing CAFO regulation around the state.

“So you don’t care what the county says?” Marshall asked Sauer.

“I don’t really care what they say.”

“You don’t care what the town says?”

“I don’t care.”

“You’re going to do what you’re going to do and they’re going to have to take it?”

“I’m going to dot the i’s and cross the t’s, and we are going to do what the law requires.”

Sauer’s feelings toward the community appeared to further darken.

The town last amended its CAFO regulations in March 2022. About two weeks later, the Polk Burnett Farm Bureau sounded the alarm on the “anti-agriculture ordinances” being enacted in northwest Wisconsin.

Sauer shared the post on social media with added commentary: “Crazies are at it some more! I hope they don’t write these while eating!” he wrote. “They definitely are selfish bastards that want what they want and could care less about others.”

It’s been more than four years, and Cumberland still seeks state approval. After Sauer’s application was rejected last spring, he returned with a smaller plan to house up to 19,800 swine.

Asked how he would respond to community members’ grievances, Sauer remarked he felt much the same way.

“The lies. The misconceptions. Just the flat lies,” he said. “If I was to point fingers — I mean, we were getting abused more than anyone else.”

This story is a product of the Mississippi River Basin Ag & Water Desk, an editorially independent reporting network based at the University of Missouri School of Journalism in partnership with Report For America and funded by the Walton Family Foundation. Wisconsin Watch is a member of the network.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us