Steve Vavrus on Wisconsin's hot, smoky, dry summer of 2023

By Zac Schultz | Here & Now

September 8, 2023

Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts co-director Steve Vavrus explains how the summer's extreme heat, wildfire smoke and drought reflect growing challenges for the state in a warming world.

VIDEO TRANSCRIPT

Zac Schultz:

Northern Bayfield and Douglas Counties reached the highest drought rating possible recently, marking the first time any part of Wisconsin has been designated with exceptional drought since the monitoring program began more than 20 years ago. This, while flood warnings span the southeast corner of the state. And this week, red flag warnings for extreme fire danger were issued in southwest Wisconsin as temperatures continue to soar. Here to help us understand the convergence of these extremes is the co-director of the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts, Steve Vavrus. Thanks for joining us today.

Steve Vavrus:

Thank you for having me.

Zac Schultz:

Now, most people that understand climate change is real also realize that weather patterns will continue to get more extreme, but do we need to redefine extreme? I mean, what is extreme? Is it 100 degrees at the beginning of September and the start of school extreme anymore, or is it going to get a lot worse, and this will look like the good old days in a few years?

Steve Vavrus:

It's a great question. We have shifting baselines right now when it comes to climate, that what seemed ordinary, or what may be seeming more ordinary in the future, would've been considered extreme years ago. We saw that for sure in the South this summer, Phoenix having its hottest summer on record and breaking all sorts of extreme 100-plus-degree days. And that certainly looks like the future we're heading toward, and so the definition of an extreme may well change. I'm afraid that people are becoming a bit numb to records, for example. We seem to have record after record when it comes to weather and climate these days, and it's easy for people to start to think, "Wow, this is just the new normal."

Zac Schultz:

When we talk about an exceptional drought in the far northern tip of Wisconsin, can we put that in context of what people think of as a drought? Because once we get into these words of moderate, severe, extreme and then exceptional, I mean, exceptional almost sounds good in some ways.

Steve Vavrus:

Right, we have to be careful with the terminology we use. When it comes to drought, we do have a pretty objective way, as objective as it can be, for evaluating drought. The United States Drought Monitor comes out every week as a new map that evaluates drought conditions across the country, and the authors make a decision about what category of drought to put different parts of the state or each state in. And so, as you mentioned, exceptional drought, the highest drought category right now in far northern Wisconsin, as well, as of today, parts of southwest Wisconsin. And this highest designation of drought category is the first time in Wisconsin that level has been reached since the drought monitor began in 2000.

Zac Schultz:

A lot of Wisconsin's infrastructures, homes, businesses, schools, roads, were designed and built for a different era. How prepared are we for this new reality?

Steve Vavrus:

That is something we really need to face and look at hard, because, as you say, we built our infrastructure for a climate that no longer exists, and it's not going to exist in the future, most likely. And so, decisions on long-term building, road conditions that can withstand heat, culverts that can withstand large storm runoff events, building homes that are more able to cope with hot days, and even public health decisions about what we do during heatwaves, those are all sorts of decisions we need to be facing, and we need to face 'em quickly. And, fortunately, some of them have win-win opportunities. For instance, if we clean up our air by reducing carbon emissions, we also improve air quality, which improves things like asthma, and can extend lifespans.

Zac Schultz:

So when we talk about policy makers, most Republicans in the legislature either deny the existence of climate change, or, at the very least, don't wanna see the state involved. But what role do federal, state, and local government have in dealing with this crisis?

Steve Vavrus:

Well, there's a lot the government can do, and I think it falls along the lines of both mitigation and adaptation of climate change. So when we talk about mitigation, we're talking about ways to reduce the problem in the first place. How do we reduce the amount of heat-trapping pollution we create? Are there any ways that we can draw some of that heat-trapping pollution down out of the atmosphere? The other way is through adaptation, so accepting that climate change is happening, and it's going to happen, and it's going to impact us. What are the ways that we can change our strategies, our operations, our way of life to adapt and cope with this new reality?

Zac Schultz:

As the director of the state climatology offices, are you also working with the agricultural industry? Are farmers early adapters in some of these areas, since they're literally on the ground, they see the reality as it exists day to day?

Steve Vavrus:

Farmers are amazingly resilient when it comes to weather and climate variations. I'm always struck by how ingenious they are about coping with these extremes that Wisconsin experiences. So things like more drought-resistant crops is something that has emerged over the last few decades, and has paid off in a big way this summer with our drought conditions. But even farmers, as resilient as they are, can face difficult conditions, like we've seen this year, where we went from one extreme of record wetness, from January through April, to now near-record dryness thereafter. And so these kinds of challenges are ones that even our farmers have difficulty coping with.

Zac Schultz:

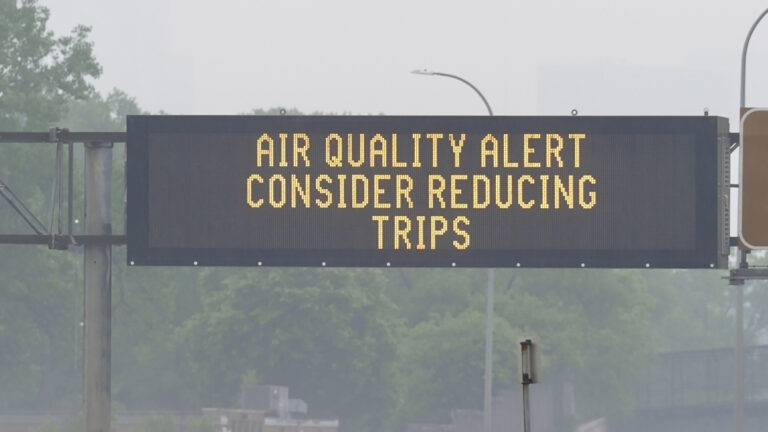

There have been a lot of assumptions in recent years about Wisconsin as a possible climate refuge in the years to come. Is that still true? I mean, there were a lot of people who were very surprised by the amount of wildfire smoke they were breathing all summer long, and all of a sudden, the comparisons to the heat in Phoenix or a hurricane in Florida don't feel quite as accurate.

Steve Vavrus:

I think a lot of people who are advocating for Wisconsin and the Great Lakes as a climate haven have needed to take a second look after this summer. As we've seen, we are not immune to weather variations and climate change. The wildfire smoke caught everyone off guard. In all the concerns about climate change, wildfire smoke was not one that rose to the level that we saw in the past few months, but yet, there we were in late June, experiencing some of the worst air quality in the world. And so, that was one of these unknown unknowns when it comes to weather and climate variations. But we do need to rethink. I think the people who are advocating Wisconsin as a climate haven do need to rethink that, because we are not immune by any stretch. And we've seen it this year with the drought, the heavy rainfalls, and then, recently, the extreme heat.

Zac Schultz:

For those of us with young kids, will the world be fundamentally different for them as adults? I think a lot of us can relate to stories our parents grew up. They were somewhat similar, if we lived in the state long enough, but are they going to have a different reality?

Steve Vavrus:

They will have a different reality, and that is just something we need to accept. But Wisconsin will still have a lot of similarities in the future to what it has now and what it's been in the past. I am reminded of this term, shifting baselines, which comes from ecology, where people get used to the climate, weather, or environment and nature that they grew up with. And then that can change gradually over the course of their lifetimes. And then, when their kids or their grandkids become aware, they have a new shifting baseline. They don't know what it was like 50, 100 years ago when you or your parents or grandparents were young. And so I think this same concept of shifting baselines applies to climate change as well.

Zac Schultz:

Is there a silver lining out there? Is there any hopeful news about, you know, our ability to adapt and survive, that maybe kids may not remember it the same way that grandpa did, but that they will still be okay, that we can adapt as a society?

Steve Vavrus:

Absolutely. We need to stop thinking doom and gloom about climate change because if we do, it kind of becomes a self-reinforcing cycle and makes people just throw up their hands and say, "Oh, it's all bad news. There's nothing we can do about it." But there is a lot we can do about it. And we need to point out success stories. And a really good example of a success story is how we're coping better with extreme heat. People may be aware or remember the Chicago heatwave of 1995, which killed hundreds of people. After that, Chicago and other cities around the country started taking heatwaves a lot more seriously as a public health threat. And they adopted heatwave action plans, which have been implemented around the country, and those have been remarkably successful. For example, late August, the heatwave that struck the upper Midwest was comparable in magnitude to the 1995 event, and yet, I've heard very little in terms of major mortality coming out of the Midwest. So a non-event can be a great event, it can be a great success story, and we need to point to those as ways that we can adapt and ways that we have co-benefits, because we'll always have heatwaves, regardless of climate change. So these are things we can do to make ourselves more resilient to weather variations, regardless of climate change.

Zac Schultz:

All right, Steve Vavrus, the state climatologist and the co-director of the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts, thanks for your time today.

Steve Vavrus:

Thank you, Zac.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us