Phosphorus Offers A Window Into Complexity Of Waukesha Water Deal

The city of Waukesha takes pride in its wastewater treatment plant.

February 14, 2017

Waukesha Clean Water Plant

The city of Waukesha takes pride in its wastewater treatment plant. But don’t ask for it by that name. So much does the city esteem its effluent that the facility that treats it is literally called the Clean Water Plant.

This plant is a big part of Waukesha’s argument that it can use Lake Michigan water with minimal environmental impact. In a long-sought and historic decision in June 2016, Waukesha became the first city not inside the Great Lakes Basin to get approved to use one of the five lakes as its drinking water source. Under the Great Lakes Compact, a complex binational agreement that governs access to the lakes, Waukesha must return as much water as it takes out. As agreed upon, the city plans to use an average of 8.2 million gallons per day, and return that water with discharges from its Clean Water Plant into the Root River, which flows into Lake Michigan at Racine.

State environmental officials currently deem the Root River “impaired” under the Clean Water Act. This designation is largely related to the river’s high concentrations of phosphorus. Phosphorus is one of the most essential chemical elements for life on Earth, and one of the biggest culprits in nutrient pollution, which occurs when too much of a given nutrient enters a body of water, throwing off its ecological systems. It typically enters water bodies via runoff from farms, where it’s plentiful in fertilizer and animal waste, as well as through urban runoff from lawns and stormwater from roads when people spread phosphorus-containing compounds to melt ice.

Waukesha officials say their treatment plant will release water with lower concentrations of phosphorus and therefore, they argue, improve the quality of the Root River.

Racine Mayor John Dickert has raised fears about his city getting a raw environmental deal, with phosphorus- and pharmaceutical-laden wastewater repelling anglers and beachgoers and their tourism dollars from the Root. State Rep. Cory Mason, D-Racine, has said the discharge could increase the risk of flooding in some neighborhoods, and in a 2012 comment that still makes Waukesha officials shake their heads, declared that Racine is not “Waukesha’s toilet.”

But Waukesha’s water engineers continue to insist that their approach is scientifically and environmentally sound, and that the design of the plant makes it impossible to discharge untreated sewage to the Root.

“We’re adding flow at a much lower [phosphorus] concentration, which means it’ll lower the concentration of the river,” said Dan Duchniak, general manager of the Waukesha Water Utility.

Waukesha still has to build additional infrastructure to carry its treated wastewater to the Root River, and construction won’t begin until 2019 at the earliest. This water won’t start flowing into the river until 2022 or 2023, Duchniak said. Between now and then, the city is working on expanding its wastewater treatment plant and improving its phosphorus treatment systems.

Duchniak is still waiting to hear how the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources will regulate the city’s discharge. His goal is for the treated wastewater to have a phosphorus concentration lower than .075 milligrams per liter, which is the maximum level in the state’s phosphorus standards for streams. The standard for rivers is a little bit higher, at 0.1 mg/L, and monitoring has shown the Root on average has a concentration of about 0.13 mg/L.

Waukesha’s discharge of 8.2 million gallons alone would likely have little impact on the 6 quadrillion-gallon (that’s 15 zeros) Great Lakes system as a whole. Moreover, Lake Michigan is nowhere near to having the phosphorous problems that have fed massive algal blooms in Lake Erie. In Wisconsin alone, 22 cities already discharge wastewater to Lake Superior or Lake Michigan, and these remain comparatively clean lakes when it comes to nutrient pollution.

However, 8.2 million gallons is a much bigger proportion of the Root River’s flow, and the argument over phosphorus offers a window into the complex scientific decisions that will come into play if more cities follow Waukesha’s lead and try to tap into Great Lakes water.

Dilution is or is not the solution

Essentially, the argument over phosphorus in the Great Lakes comes down to whether one agrees with the idea that diluting a chemical’s presence in the water is an environmental benefit. This isn’t a new argument: In matters from chemical pollution to plastics in large bodies of water, one often encounters the phrase “dilution is not the solution to pollution” — or, from another perspective, “dilution is the solution to pollution.” But the complex hydrology at work doesn’t readily lend itself to either aphorism.

Scientists use a few distinct concepts to measure the presence of contaminant chemicals like phosphorus in water. The “load” is the total amount of the chemical going into the water body or watershed as a whole. The “concentration” is the ratio of a given chemical to water — measured in units like milligrams per liter or parts per billion. The city of Waukesha is basically saying that its discharge will increase the Root River’s phosphorus load but reduce its concentration, and that this is a net benefit.

Once the treated water travels through the Root River, it flows into Lake Michigan and becomes part of a larger circulation that gradually carries water north into Lake Huron, south to Lake Erie, and then east over Niagara Falls and into Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River. Phosphorus doesn’t just ride the current, of course — it also feeds into the complex nutrient cycles of aquatic plants, animals, and microorganisms.

In large part because of those nutrient cycles, the forms phosphorus takes are important to consider alongside its load and concentration in water. Organisms will use phosphorus differently depending on whether it’s dissolved in water or suspended in particulate form. And depending on how various natural cycles and organisms handle phosphorus, it may have different impacts on other organisms and processes — meaning variations will ripple out in unexpected ways.

The location of phosphorus in a lake is also important. Ecology isn’t the same near the shore and out in the middle of a big, deep body of water. The Great Lakes are relatively healthy and resilient considering the many large urban areas along their shores, but each can still have localized algae problems in near-shore areas. No lake has it anywhere near as bad as Lake Erie, where phosphorus runoff from farms has accumulated to feed algal blooms that can be seen from space and have temporarily shut down drinking water sources for thousands of people.

Waukesha’s argument about dilution gets mixed reviews from scientists and environmental advocates.

“If the city is able to get the phosphorus concentrations in their discharge down to the levels that they’re saying they can, then it should result in a lower phosphorus concentration in the river itself,” said Harvey Bootsma, a freshwater sciences professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. “From that perspective, their argument is valid.”

One catch is that phosphorus can still create localized algae problems. Sewage plants generally do a good job of removing particulate phosphorus from water, but not so much dissolved dissolved phosphorus, which pesky algae organisms like Cladophora crave, Bootsma said.

The Great Lakes’ phosphorus load has gone down significantly since the 1970s, and Lake Michigan consistently comes in under the target set by international agreements. Offshore concentrations have declined, but higher-concentration hotspots could still occur near shores, where rivers, sewer outflows and runoff from roads and farms converge. In Lake Michigan, this has meant an increase in near-shore blooms of Cladophora.

Scientists may not actually know enough about near-shore phosphorus concentrations. David Bunnell, a researcher with the U.S. Geological Survey, calls that “one of the gaps in monitoring” of phosphorus in the Great Lakes.

“What more people are trying to say now is in the near shore, ‘Are there local areas where phosphorus concentrations are higher?’” he said.

However, the Root River itself, despite being classified as impaired, contributes less to Lake Michigan’s phosphorus load than the Lower Fox River to the north or St. Joseph River to the east, he added.

In a sense, dilution has clearer benefits in the Root River than in Lake Michigan, said Mary Evans, a research ecologist with USGS.

“For creatures in the river, generally the concentration they’re experiencing…is considered to be what matters,” she said. “For a receiving water body and the response of a bay or of Lake Michigan to nutrient loading, in general the load is considered to be what matters. There are specific fluctuations where parts of a lake can act more like a flowing water system and react more to the concentrations.”

One good piece of news is that even if Waukesha releases much more phosphorus into Lake Michigan than it says it will, it’s not likely that an increase would cause problems in Great Lakes to the east. The overwhelming majority of Lake Erie’s troublesome phosphorus comes from local sources — only about 6 percent of it seems to be coming from Lake Huron, Evans said. This suggest that not much phosphorus travels from Lake Superior or Lake Michigan to Lake Huron in the first place.

Whatever the impact, more phosphorus is more phosphorus. Cheryl Nenn of Milwaukee Riverkeeper, an organization that has opposed giving Waukesha access to Lake Michigan’s water, fears more will ultimately hurt the quality of the Root River.

“Even if you’re discharging wastewater that’s at a lower concentration level, it’s still adding a cumulative phosphorus load,” Nenn said. “Any addition of phosphorus would be contributing to the impairment.”

Nenn also admits that if the Root’s water quality gets worse during the 2020s or later, it won’t necessarily be Waukesha’s fault.

“If the water quality got worse…it’s going to be very hard for [the city of Racine] to prove that it’s because of a minimal increase in discharge from the city of Waukesha,” she said.

Phosphorus is just one factor in how Waukesha’s wastewater will affect the Root River. The discharge will also add a lot of water to a river that often has pretty low flow.

David Ullrich, executive director of the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative, a coalition of dozens of U.S. and Canadian cities in the Great Lakes Basin that oppose the Waukesha deal, is concerned that the increased flow could raise the risk of flooding, or stir up sediments from the river bed with unknown consequences.

“The concern is always cumulative — death by a thousand cuts or something like that,” Ullrich said.

What if there are more Waukeshas?

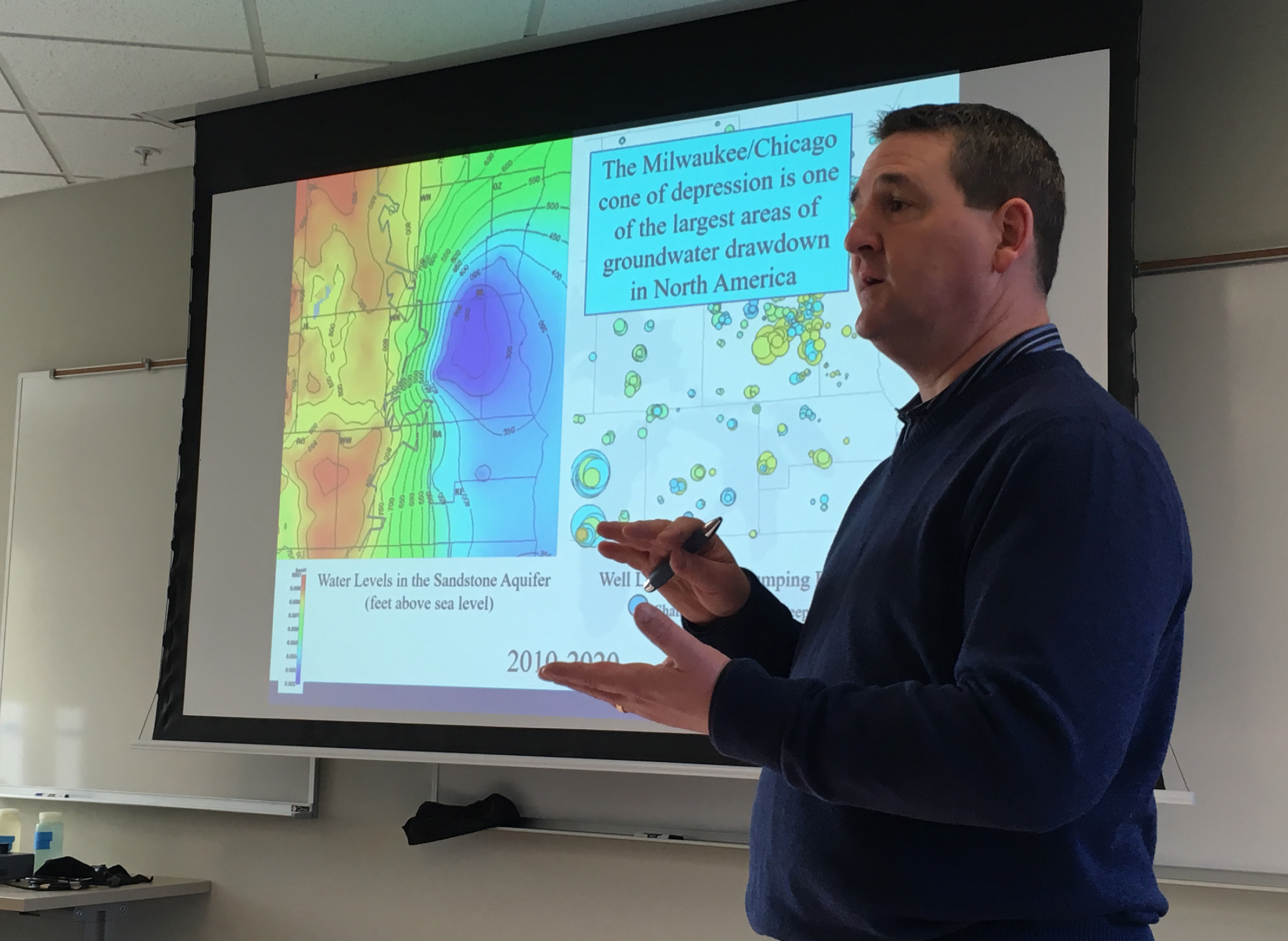

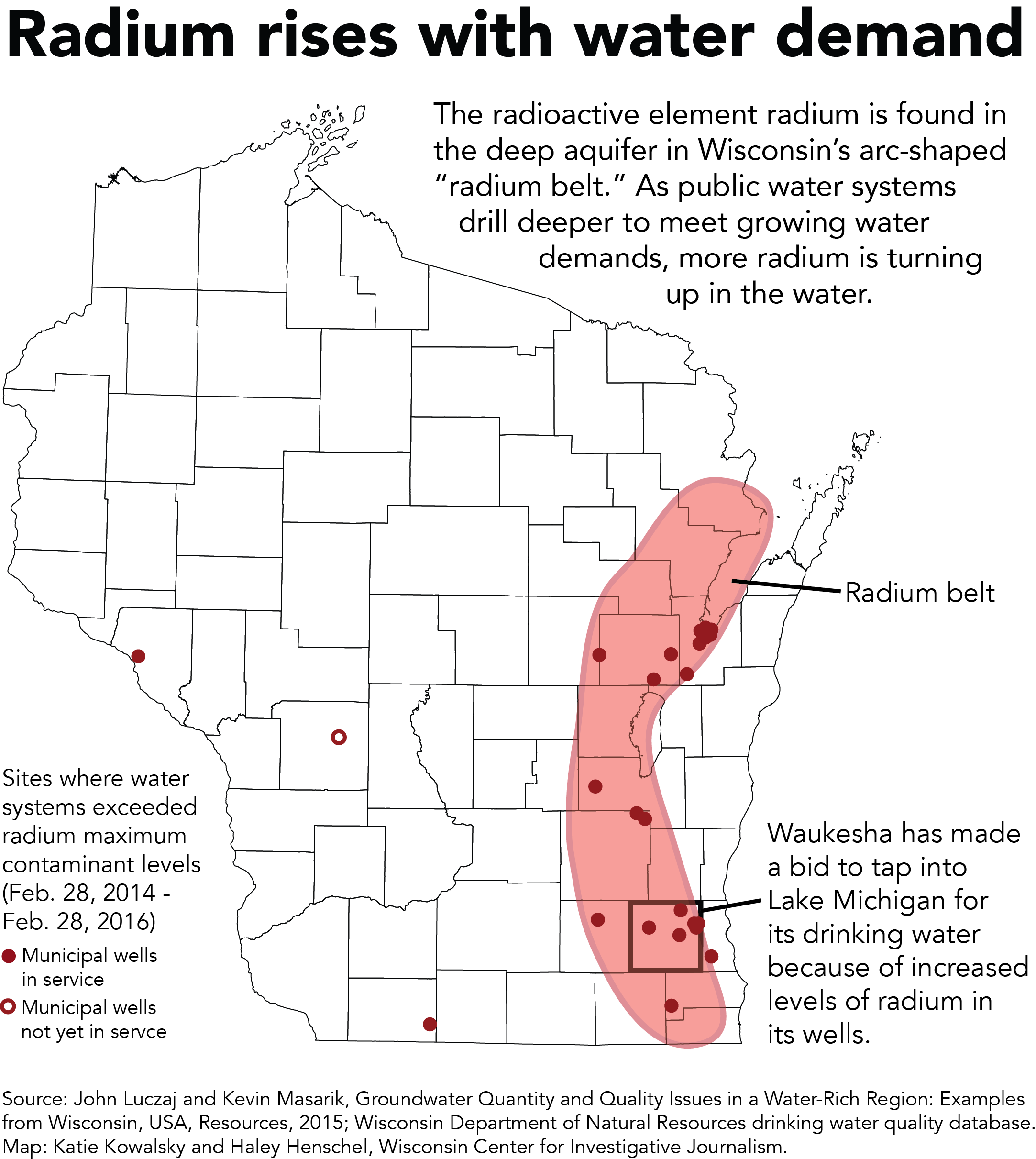

Waukesha sought Lake Michigan water to solve a legitimate problem: the fact that its groundwater is increasingly tainted with radium. There are a lot of reasons why its decision is so contentious, but the biggest one is because it’s a first.

The Great Lakes Compact entitles cities entirely or partially within the Great Lakes Basin to access the lakes’ water. Cities that are not themselves within the basin, but are in counties straddling the basin’s border, may seek access. However, they must seek approval from a Compact Council of the governors of all eight Great Lakes states, showing that their use of water can meet certain environmental benchmarks, and that drawing water from the lakes is their only reasonable option. The Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec participate in Great Lakes Compact governance as well, but for them to vote on the actions of an American unit of government would violate the U.S. Constitution.

Waukesha is the first community to petition for Great Lakes water as a city straddling the border of the Great Lakes Basin. Its success sets a precedent for dozens of other communities that are likewise just barely outside the basin.

Opponents of the unanimous decision to let Waukesha go ahead believes it puts the Great Lakes Compact on shaky ground. They don’t trust that state regulators will be able to hold the city to its environmental promises, and contend that Waukesha had other alternatives, like installing additional measures for removing the radium that gets into the water from eastern Wisconsin’s strip of naturally occurring radium deposits. Waukesha has countered that additional radium treatment methods would consume additional water in the course of treating it, thereby speeding the groundwater drawdown that caused the contamination.

“With this being the first one under the compact, it’s just very important that it’s done right,” said Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative executive director David Ullrich. His organization is petitioning the eight Great Lakes governors to reverse their decision on Waukesha, and may go to federal court if that effort fails.

Again, even opponents of the Waukesha decision realize that the city alone would likely have little impact on the overall Great Lakes system or even Lake Michigan. But if other communities follow, then cumulatively they would have a greater environmental footprint. Don’t expect dozens of cities to stampede to the Compact Council just yet — Waukesha spent more than a decade and millions of dollars in its bid, and will have to spend millions more just to build the infrastructure to discharge the new wastewater. It’s not an easy or cheap process.

But groups like the Initiative still aren’t satisfied that cities that make it through the approval process will be held to strict standards of need and environmental quality.

“The ultimate question here is, did they meet conditions and standards?” Ullrich said. Whatever the outcome with Waukesha, he wants the Compact Council to rethink its standards and processes for weighing requests from straddling-county communities.

What’s not new, though, is discharging wastewater into one body of surface water or another, including rivers and streams that feed into Lake Michigan.

Dan Duchniak, head of Waukesha’s water utility, points out that two other cities discharge wastewater into the Fox River — not the same Fox River as mentioned above but a different one that’s a tributary of the Illinois River — before it flows through downtown Waukesha, but he said this hasn’t harmed fishing, watersports, or development along the river. So he’s not convinced living downstream from a wastewater discharge has to be bad.

As a onetime city of Racine employee, Duchniak added that he wouldn’t want to harm that community either. He contends that by adding to the flow of the Root River, the discharge will make the river better for fishing.

“One thing that I’d like to stress is that this is the norm,” Duchniak said. “A lot of people, I believe, are trying to make this more than what it really is. Ninety-four percent of the wastewater utilities in the state discharge to a river or stream. It’s not like this is something new, or we’re looking at a cheap way out or looking to do something that’s unprecedented.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us