New Opioid Policies Face Structural Obstacles, Entrenched Attitudes

One barrier to more doctors prescribing medications to treat opioid addiction? Many are confused about how to navigate the regulations, or they're not addiction specialists and are intimidated at the prospect of trying to treat patients with substance use disorders.

February 28, 2017

Opioid addiction medication molecules illustration

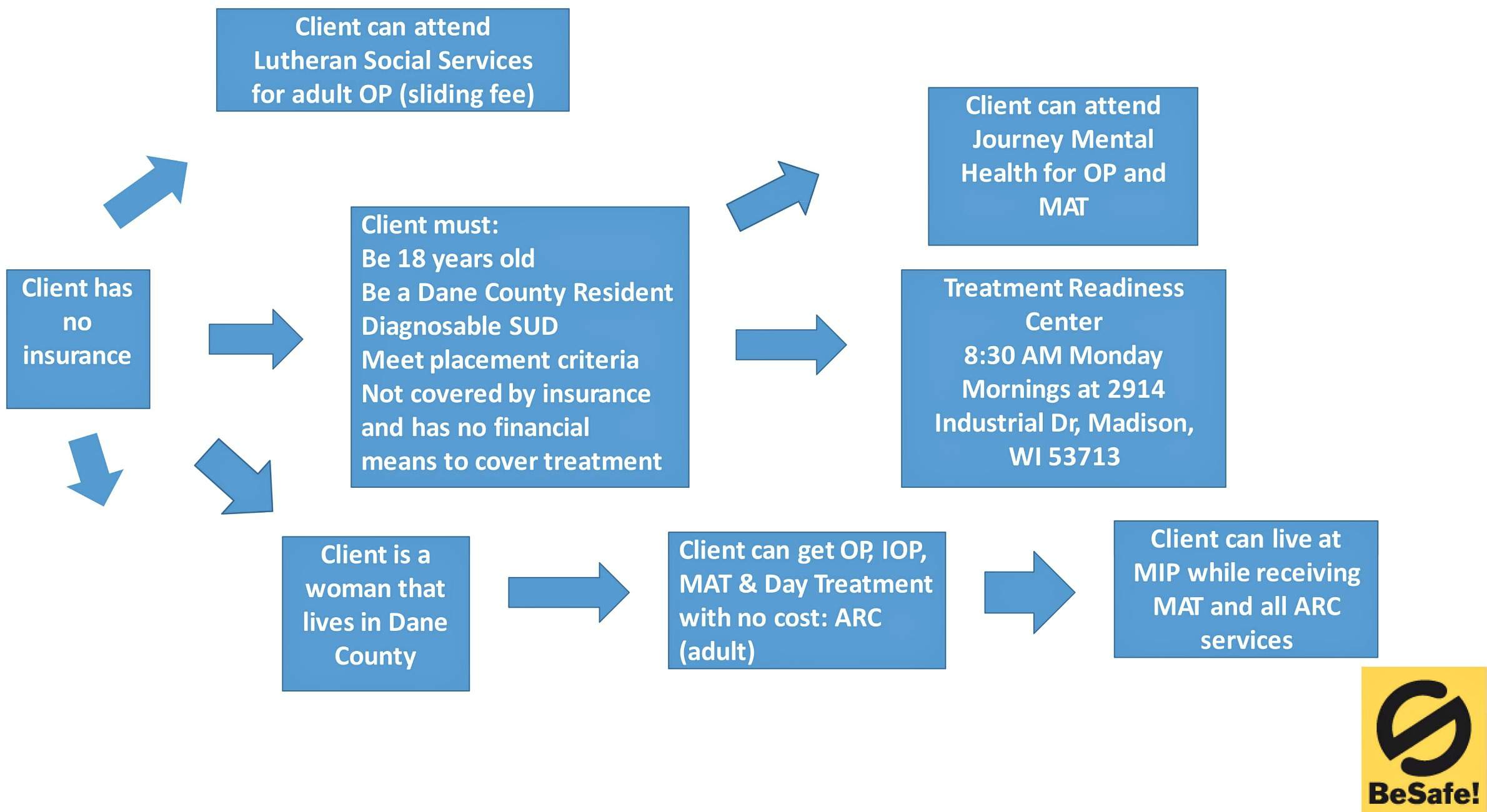

People in the Madison area looking for treatment of an opioid addiction have a guide they can use to find out where to start. The document, created by a non-profit called Safer Communities, is 40 pages long — 33 of those pages are flowcharts helping people figure out which service providers to use depending on which health insurance policy they have and other individual circumstances. It aims to simplify a tough decision-making process, but it’s still dizzying to look at.

“Imagine trying to figure it out in opioid withdrawal,” said Skye Tikkanen, a substance abuse and mental health counselor with Madison-based Connections Counseling, who is in long-term addiction recovery herself. She has played an active role in reshaping Wisconsin’s policies on addiction and treatment, including working with state Rep. John Nygren, R-Marinette, on his opioid-focused HOPE Agenda.

Along with many other people in the substance-abuse field in Wisconsin, Tikkanen believes the state is making progress in tackling its opioid crisis, but also sees plenty of barriers remaining, especially in practical limitations on access and in attitudes that keep policymakers and medical professionals from embracing medication-assisted treatment for addicts.

Legislation in the HOPE Agenda has expanded access to treatment, provided emergency responders with the life-saving overdose antidote naloxone (better known by the brand name Narcan), and offered some people who help overdose victims some protection from criminal or civil liability. Nygren has introduced 11 additional bills for a planned special session of the state legislature in 2017. These proposals include allocating more money to create treatment programs in underserved areas (AB 8), funding more treatment options for nonviolent criminal offenders (AB 2), creating a consultation program for patients with addictions (AB 9), providing public-school staff with mental health training (AB 11) and funding additional addiction training for medical professionals (AB 7). Together, these bills would begin to address some of the institutional issues that stand in the way of progress on the opioid epidemic.

On the federal level, the future of the Affordable Care Act is uncertain, but along with the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, it requires health insurance to provide more coverage for mental health and substance abuse treatment.

Tikkanen said the medical profession can bolster such policy changes by increasing the number and geographic reach of doctors offering medication-assisted treatment, but “we’re not seeing a huge increase in that so far.”

The nature of the challenge keeps evolving, especially as potent opioids including fentanyl and an elephant tranquilizer make their way into the heroin supply.

“We are seeing less people initiate opioid abuse disorders, which is what we really want to see, but there’s just more dangerous drugs out there, so people who are using are at such high risks for death,” Tikkanen noted.

The state still can’t quite meet the need for treatment with the public and private resources it has. About 300 Wisconsinites are on opioid treatment waiting lists on any given day, said Elizabeth Goodsitt, a spokesperson for the Wisconsin Department of Health Services.

Regulatory confusion

The three main medicines that clinicians with prescribing privileges use to treat opioid addiction — methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone — are regulated differently.

Methadone and buprenorphine are opioids themselves, so prescribing them to treat opioid addiction is technically illegal under the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act, which Congress passed in 1914.

For methadone, federal regulators deal with this law by requiring the drug to be dispensed at designated clinics, and that patients generally have to show up in person to receive a daily dose, gradually earning take-home privileges over several months.

In contrast, clinicians can prescribe buprenorphine, best known in a proprietary formulation called Suboxone, but need to get a special waiver from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. The buprenorphine waiver comes with an initial limit of 30 patients, and doctors must get federal permission to increase it.

Clinicians do not need to get a certification to prescribe naltrexone — best known in a proprietary once-a-month injection called Vivitrol — as it’s not as strictly regulated as the other two, in part because it’s not an opioid.

One barrier to more clinicians prescribing medications? Many are confused about how to navigate the regulations, or they’re not addiction specialists and are intimidated at the prospect of trying to treat patients with substance use disorders.

“As soon as we say ‘opioid addiction,’ people start stumbling because they are not sure whether they are authorized to do it or not,” said Aleksanda Zgierska, a physician and professor with the University of Wisconsin’s Health Innovation Program and president of the Wisconsin chapter of the American Society of Addiction Medicine. Through this group, she works to help more doctors get the information and training they need to treat substance use disorders.

More non-specialized primary-care physicians are getting interested in opioid treatment because they see the problem afflicting their communities, Zgierska said. And in a way, doctors who encounter a lot of patients with drug problems might be more experienced than they think, she added.

Zgierska questions the basic assumptions behind the very specific way in which opioid addiction treatment is walled off through specialization and regulations. She uses diabetes — which, like addiction, is a chronic disease — as a parallel.

“We don’t have second thoughts about authorizing the majority of treatment for diabetes — for that, primary care physicians can prescribe the medications that are needed,” Zgierska said. “It’s just assumed that we prescribe it, and patients are commonly seen within primary care within the scope of our practice.”

No one faults a diabetic for being physically dependent on insulin, or questions the wisdom of providing it as a crucial step in medical treatment. But with drug addicts, there’s more hand-wringing about addressing a patient’s behavioral habits if that person is to take medication.

Zgierska believes addicts should receive a balance of medication and behavioral treatment. However, she questions whether concerns about providing behavioral treatment should prevent a family doctor from prescribing the addiction medicines, especially in areas of the state where there aren’t enough mental-health resources.

“We don’t make it contingent on the patient going and seeing a nutritionist or a personal trainer,” Zgierska said of diabetes treatment. “We just start with patients where they are at.”

Wisconsin’s health regulations on opioid treatment are generally are no stricter than federal rules. But they can make it tough to fit together the pieces of a holistic treatment plan.

Skye Tikkanen, for instance, is licensed as both a mental-health counselor and a substance-abuse counselor. The medical profession might treat substance abuse as a form of mental illness, but under Wisconsin’s regulations there’s one set of rules for outpatient mental health and another governing substance abuse.

These regulations differ on all kinds of matters. For instance, mental health clinics must have a plan in place to help patients who have a crisis after business hours. The state does not have a parallel regulation for substance abuse clinics, though some specific emergency services are required to be on-call 24/7. And substance abuse and mental health counselors have to meet different requirements in order to take on a supervisory role at their clinics.

The separate regulations also give mental health counselors more freedom to collaborate with other clinicians for a patient’s care, Tikkanen said.

Having two sets of regulations also means a facility must be dually licensed if it wants to offer both medication and mental health counseling under one roof, and that impedes methadone clinics who’d like to do so, said Dan Bizjak, who is president of Recovery and Addiction Professionals of Wisconsin and worked at a methadone clinic in Milwaukee before beginning his current job as a social worker at Rogers Memorial Hospital in West Allis.

Ideally, Tikkanen would like for these two sections of regulations to be combined into one consistent set of rules.

“Being a dually licensed counselor, it is a challenge to figure out which statute I need to listen to in order to protect my clients,” she said.

Geographic barriers

Licensed methadone clinics in Wisconsin treated 8,160 people in 2016, said DHS spokesperson Elizabeth Goodsitt.

One HOPE Agenda law (2015 Wisconsin Act 263) eliminated a requirement that people receiving treatment at a methadone clinic must live within 50 miles of it. (A patient manual on the Wisconsin Department of Health Services’ website contains outdated information about this rule; Goodsitt said the agency is working to update it.) But the change doesn’t alter the fact that large swaths of Wisconsin are nowhere near to one of the state’s 19 methadone clinics. Like many mental-health disparities, this is particularly tough on rural areas in the north of the state — the farthest-north clinic is in Wausau.

Buprenorphine and naltrexone prescriptions may not tether patients to clinics in the same way as those for methadone, but there’s not always a provider nearby. The federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration provides an online directory of doctors who prescribe buprenorphine. (It isn’t comprehensive, as a doctor can have a waiver for prescribing but opt out of being listed in the directory.) The SAMHA directory lists 229 doctors in Wisconsin — less than one percent of the state’s licensed MDs and doctors of osteopathic medicine. Together, these doctors practice in 34 of the state’s 72 counties, and have reach more into rural areas than methadone clinics. There is no similar federal or state directory for naltrexone providers, but Vivitrol’s promotional website lists about 60 doctors in Wisconsin who prescribe the drug.

But as the geographic reach of some treatment options for opioid addiction is expanding, so too is abuse, especially in rural areas.

Much of rural Wisconsin, and parts of urbanized Milwaukee and Rock counties, are federally designated as mental health professional shortage areas. Living in such an area might not prevent a patient from getting a buprenorphine or naltrexone prescription from a physician, but can make it more difficult for them to access the behavioral component of a well-rounded treatment program.

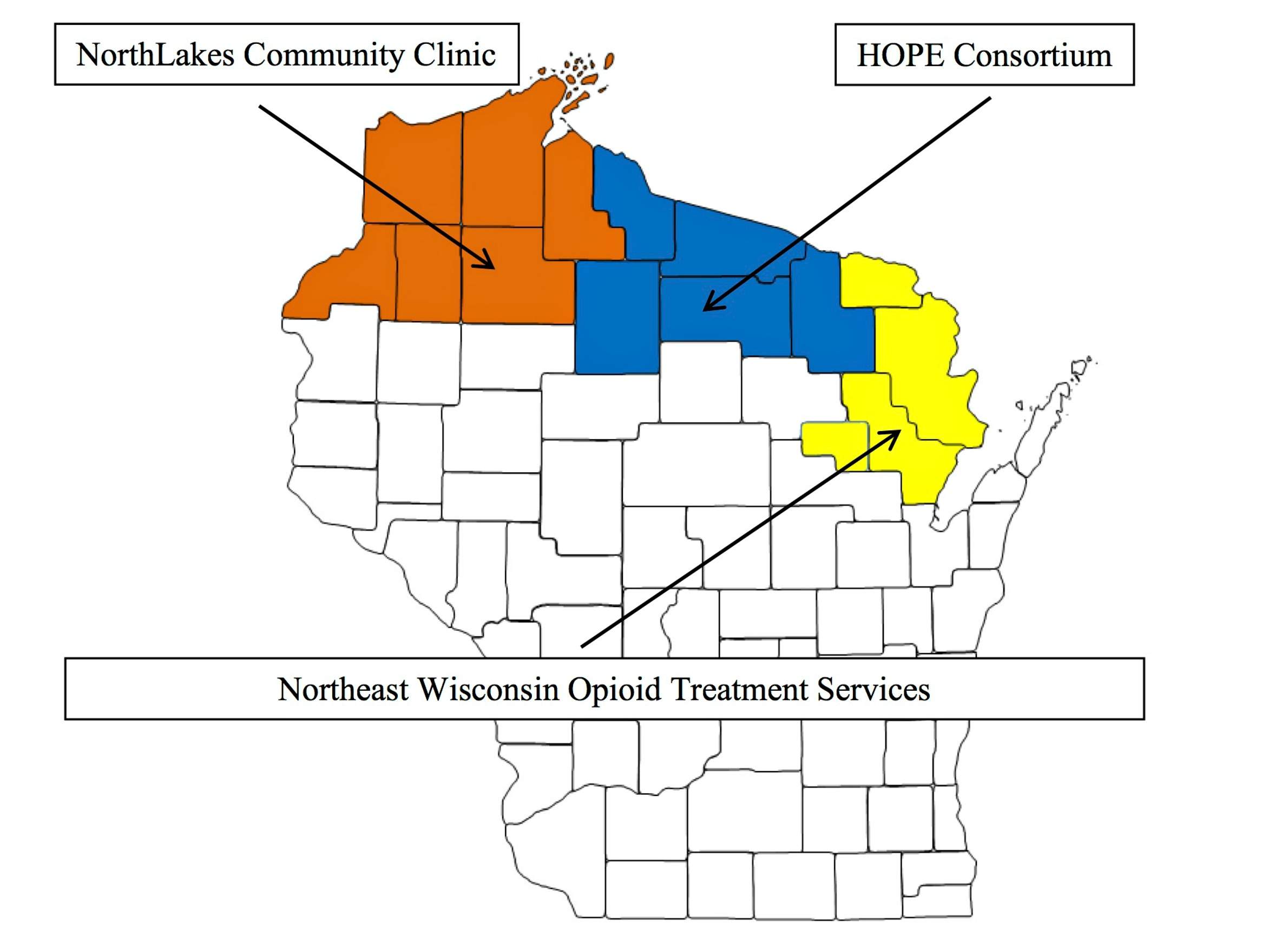

Legislators have made some steps in filling the void. New opioid treatment centers created under the HOPE Agenda target gaps in Wisconsin’s northernmost counties. Caroline Krause, a policy advisor to Rep. John Nygren, said these centers already are encountering greater demand than they anticipated. The 15 counties these three centers collectively serve have no methadone clinics, and just five have buprenorphine-prescribing doctors listed on SAMHSA’s public directory.

In the case of methadone, even if a patient living more than 50 miles from a clinic is now legally allowed to get treatment there, the distance is still a huge practical barrier for someone to deal with every single day. But even being within 50 miles of a clinic doesn’t necessarily make it practical.

“Let’s say the patient lives 49.9 miles away … When you think about what it means when they have to go to medication pickup or going every day for months, they have to drive 49.9 miles one way and back,” said UW physician Aleksanda Zgierska. That distance is far enough for anyone, especially if they’re balancing a job and/or child care, but a person in recovery might not be in the best financial shape and might not even have a car.

The clinic-based system of methadone treatment, and the way the state regulates it, can slow down treatment and arguably make it difficult for a clinic to take on more patients.

For instance, a doctor at a methadone clinic may decide to gradually reduce a patient’s dosage. Current regulations require a patient to visit the clinic any time the dosage changes by any amount.

“If I’m a patient and I’m going to start a taper because I’m ready to go down, I have to see a physician every time I go up or down on a dose, even if it’s one milligram,” said Dan Bizjak of Recovery and Addiction Professionals of Wisconsin.

Mark Parrino, president of the American Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence, also takes issue with this requirement.

“That creates a greater amount of physician time than is required,” he said.

In addition, Parrino said, federal and state requirements for licensing or certification can be a practical hindrance for doctors.

“I understand the value of that, but sometimes in a state, suppose you don’t have enough opportunities to take a course or take the licensing exam?” he asks.

Bizjak and other addiction-treatment professionals understand that regulations are in place to protect patients, and by no means do they see them as a general problem. Still, they’ve found the rise in opioid abuse and related deaths has revealed policy weaknesses.

“A lot of patients are asking for help but there’s not enough service providers out there, and sometimes the regulatory pieces hinder patients from getting treatment,” he said.

Stigma lingers around proven treatments

Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction has science on its side. Research has backed up the efficacy of methadone and buprenorphine, though there’s less scientific literature on naltrexone because the FDA didn’t approve it as an opioid-addiction treatment until 2010.

“Methadone is one of the most researched treatments in all of medicine,” said Michael Miller, medical director of the Herrington Recovery Center at Rogers Memorial Hospital in Oconomowoc and a board member with the American Board of Addiction Medicine. Additionally, more Americans are beginning to understand addiction as a chronic illness as opposed to a personal failing, and even traditionally “tough-on-crime” politicians are acknowledging opioid abuse as a public-health crisis rather than simply a criminal justice issue. But stigma remains around addiction treatment, especially around methadone, as does its long-term imprint on policy and the health care system.

Critics of medication-assisted treatment argue that it merely replaces one addiction with another. This argument does not square with medical facts. Addiction is a chronic condition that can be managed but not cured like an infection, so any effective treatment will be a long-haul affair.

The managed aspect of medication-assisted treatment makes a big difference to someone trying breaking the substance-abuse cycle.

“You’re switching people from something that they’re taking on their own schedule to something that they take on a very fixed schedule,” Miller said. “It does create a state of physical dependency, but there’s a ton of literature out there on why physical dependency and addiction are not the same thing.”

Illicit opioids can have impurities, like fentanyl-laced heroin that’s causing more overdose deaths. A given user might also alternate among different drugs if their availability is erratic, and might use them in unsafe combinations with other kinds of substances such as sedatives. But a medically administered methadone pill or a monthly Vivitrol injection is a known substance, and its effects are much more predictable.

Miller credits state legislators with seeing naltrexone and buprenorphine as opportunities to expand addiction treatment in Wisconsin, especially for rural residents. That said, he cautions against ignoring the value of methadone. Because methadone is the oldest opioid-addiction medication — coming into use for that purpose in the 1970s — it’s had the longest time to gain a reputation, negative as it may be. Companies making more recently introduced buprenorphine and naltrexone products have benefited from modern pharmaceutical marketing, as well as from lobbying efforts. Because regular physicians can prescribe these newer treatments from their offices, they also don’t suffer from the stigma people attach to the physical presence of a methadone clinic.

“You will have community groups that will say ‘On the one hand, we can’t have our sons and daughters and our neighborhood dying of overdoses’ … and that same community group is likely to say, ‘But we don’t want the treatment program in our neighborhood,'” said Mark Parrino of the American Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence.

State and local governments do have the power to make life difficult for methadone clinics. Several states have limited the number of opioid addiction treatment providers and Mississippi has only one.

States also have some discretion over how to spend their Medicaid funds — something Maine’s Republican Governor Paul LePaige has used to try to steer money away from methadone and toward buprenorphine, over objections from the addiction community.

Wisconsin doesn’t have any particularly direct anti-methadone laws, but the legislators promoting the state’s new treatment-oriented policies aren’t so hot on expanding its use. In fact, the HOPE Agenda law (2013 Wisconsin Act 195) creating new regional treatment programs in northern Wisconsin explicitly states that they cannot offer methadone. The intention is that if a patient needs medication-assisted treatment, it should be with buprenorphine or naltrexone.

“We’ve seen that a lot of people who are on methadone, they end up taking it for years, and that’s not necessarily helpful because you’re technically impaired when you’re on methadone,” said Caroline Krause, a policy advisor to Rep. John Nygren.

Changing the health care agenda

Medication-assisted treatment with methadone does have its pitfalls. Researchers have found that long-term use of methadone can have negative effects on the brain. Moreover, people do sometimes abuse methadone and buprenorphine outside of medical settings.

However, Michael Miller of the Herrington Recovery Center cautions against state policies that limit the duration of medication-assisted treatment.

“Those are terrible public policies, because it’s a chronic disease and you’re not necessarily going to treat the disease with a short-term intervention,” he said.

The medical community itself has contributed to stigma surrounding medication-assisted treatment with methadone, and, perhaps more importantly, hasn’t placed all that much emphasis on addiction as a health issue over the decades. “Doctors who prescribe methadone are sometimes looked down upon,” Miller said.

Medical-school deans and medical accreditation agencies are beginning to come around to the need to educate their students about substance use disorders, Miller said. For instance, the American Board of Medical Specialties officially recognized addiction as a medical subspecialty in 2016, and plans to begin certifying doctors in it in 2017. That change addresses a deep-rooted issue: If a physician never encountered a med-school professor who knew about addiction, it breeds what Miller calls “multi-generational ignorance.”

The traditional structure of health care tends to set addiction apart from other corners of medical specialties. The standalone nature of methadone treatment is perhaps the most obvious example. But Miller also points to a lack of addiction-related departments within prominent health care networks like Physicians Plus and SSM Health Dean.

“It absolutely should be their bailiwick,” he said.

What about the climate that greets doctors and other addiction professionals in the workforce? It’s still out of balance when it comes to attitudes — and to pay.

“My field really hasn’t been recognized as a part of the medical field for a long time,” said Madison-based addiction specialist Skye Tikkanen, who holds a master’s degree in community mental health. She would like to see more scholarships offered for students interested in pursuing careers in addiction treatment, because current compensation levels in the specialty disincentivize that choice.

“If I was a sonogram tech, I would need far less school and make far more money,” Tikkanen said. “It’s hard to invigorate young people who want to pursue mental health or substance abuse counseling when they’re going to rack up a lot of student loan debt and they’re not going to get paid very well.”

The medical establishment’s growing acceptance of addiction treatment helps, but that doesn’t quite fix the problem, Tikkanen said.

“Insurance company reimbursement rates drive what we make as professionals, so that’s going to take longer to change,” she added.

Tikkanen also wants to change the overall structure of access to treatment. She sees one solution in a Medicaid-driven “hub and spoke” model adopted in Vermont. In that system, the “hub” is a centralized regional treatment program that connects patients with a localized network of doctors and clinics.

Wisconsin lawmakers haven’t advanced a specific policy proposal to adopt a hub and spoke system or something like it, but Rep. John Nygren’s advisor Caroline Krause said members of the state’s opioid task force have discussed it.

“This is something that comes up a lot, and it looks like it works,” she said. “What we keep hearing is that Wisconsin has a lot of spokes but not enough hubs. There’s all of these [treatment] opportunities but none of them are coordinated.”

The advantage is a hub and spoke system gives patients a centralized entry point to make a first contact with the treatment system and get connected with options. It increases coordination among health care providers and removes some of the barriers people run into when navigating complex insurance and treatment networks. This in itself could save lives.

“Usually the first time the door’s shut, they give up and it’s an easier choice to use again,” Tikkanen said.

Editor’s note: This report is corrected to note that a certification is not required for clinicians to prescribe naltrexone.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us