Immigration, Documentation And The Growth Of Wisconsin's Mexican-American Communities

Mexican immigrants and their descendants born in the United States comprise a growing and increasingly visible group of communities around Wisconsin.

March 27, 2018

Eagles mural at United Community Center in Walker's Point, Milwaukee

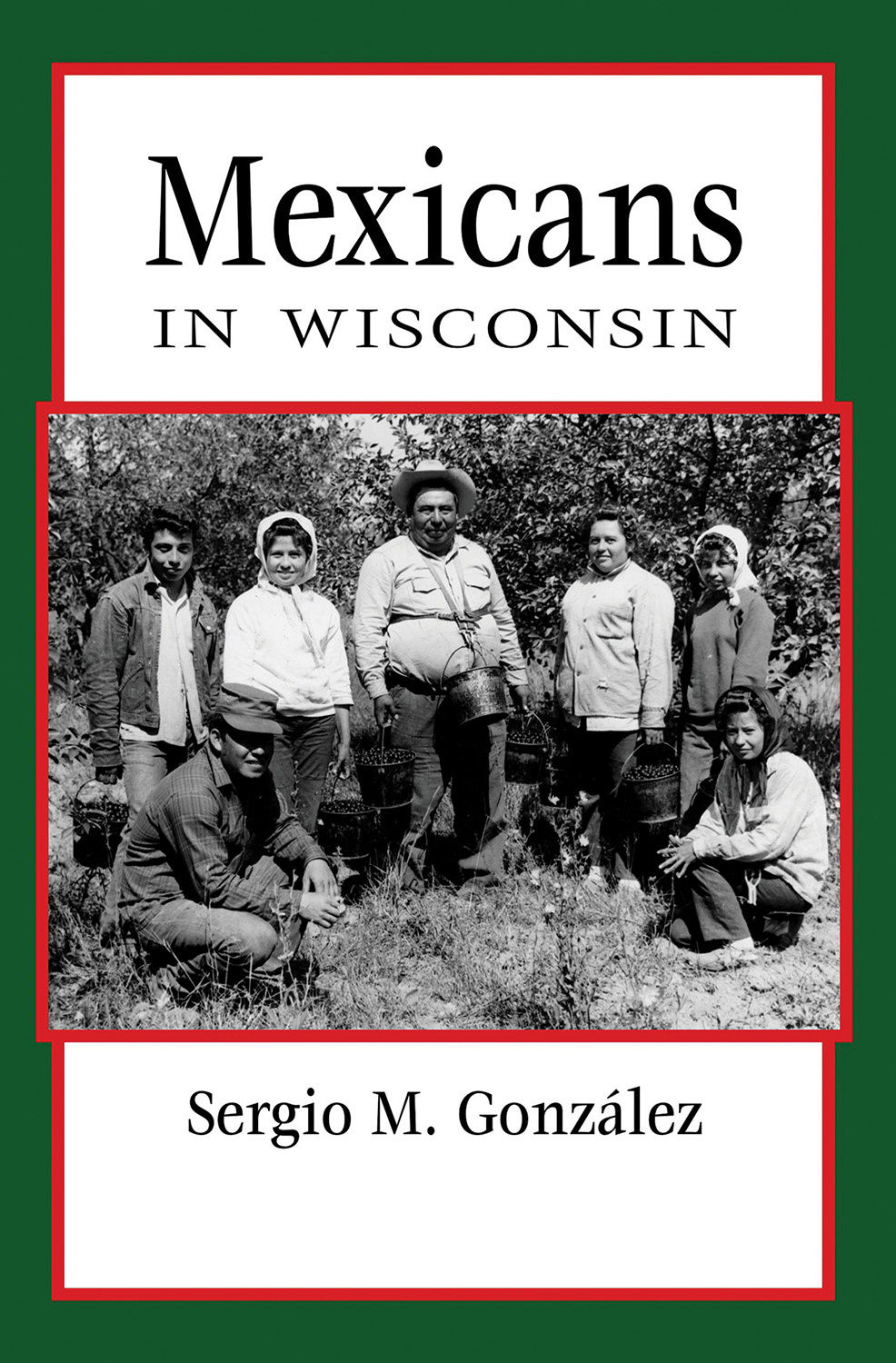

Mexican immigrants and their descendants born in the United States comprise a growing and increasingly visible group of communities around Wisconsin. First arriving in Milwaukee and neighboring cities in the first decades of the 20th century, their numbers around the state during and after World War II through federal temporary worker programs. These early immigrants were primarily migrant laborers seeking manufacturing and agricultural jobs. In later decades, Mexican-American communities established religious, business and political roots across Wisconsin. The varied experiences of these immigrants are detailed in the 2017 book Mexicans in Wisconsin, written by Sergio M. Gonzu00e1lez and published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press as part of its People of Wisconsin series. An excerpt from the book details an increase of undocumented immigrants in the 1970s and 1980s, with these arrivals contributing to an uptick in Wisconsin’s foreign-born population while the state’s number of native-born Mexican-Americans was simultaneously growing, and how a series of deportation raids and subsequent federal immigration reform helped define these communities. In the early 21st century, the ongoing prominence of immigration as a political issue in the U.S. confirms the relevance of this recent history.

Documented and undocumented immigration from Mexico to the United States grew at high rates throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s. Economists and demographers attributed the rise in immigration to a number of factors, including a series of economic crises that stunned Mexico and pushed the country’s joblessness rate to over 20 percent.

Unable to secure visas for legal immigration to the United States, some in Mexico made the decision to migrate north to find better employment and thus provide for their families back home. The decision to travel north was never an easy one for these immigrants; it involved leaving behind loved ones, homes, entire communities and a way of life.

While states along the border region became receiving sites for a large number of incoming immigrants, many Mexicans made their way to the Midwest, drawn by promises of industrial and agricultural work. Chicago trailed only Los Angeles as the urban area with the largest concentration of undocumented immigrants throughout the period.

Mexican immigration to Wisconsin continued to grow after the 1970s as factories, tanneries, foundries, canners and meatpackers began to more heavily recruit Mexican natives — through both legal and extralegal means — to fill an expanding number of grueling, low-paying positions. Immigration and Naturalization Service officials estimated that Wisconsin’s own undocumented population ranged from twelve to fifteen thousand by the end of the decade.

How one “became” undocumented in the eyes of federal law could occur in a number of ways. Some Mexican immigrants made the decision to embark on the dangerous journey across the U.S.-Mexico border without legal visas, paying anonymous brokers called “coyotes” who charged hundreds of dollars for the promise of safe passage into this country. More often than not, however, immigrants of any number of nationalities — including those of Mexican origin — who found themselves outside of proper immigration status did so after overstaying a legally approved work or travel visa.

Those who made the decision to come to the United States sin papeles (without papers) faced numerous hurdles with drastic implications for themselves and often the lives of their family members in Mexico.

Living in cities like Milwaukee without legal documentation often meant creating a life in the shadows, constantly living in fear: fear of deportation and the economic hardship that might befall their families if they lost their employment; fear of employers who abused their knowledge of workers’ immigration status and used it as a tool to dismiss surplus laborers and disrupt worker organization; and fear of a general American public that often considered undocumented immigrants at a minimum unwelcome guests and at worst “illegals” who posed a risk to local and national security.

This fear permeated all aspects of life and work for those who lived in the margins. A Mexican father who came with his family to the United States explained to the Milwaukee Journal, “You are lonely and afraid because you are not in your own country. You feel angry, but there is nothing you can do. There is nowhere to run.”

Undocumented immigrants’ feelings of dread and anxiety were often exacerbated by increased federal immigration raids at worksites in southeast Wisconsin in the early 1980s.

Latino community leaders expressed anger that undocumented immigrants of Latin American descent were targeted in massive federal raids, while those from European countries — especially those who hailed from regions under communist rule that were deemed of higher importance for national security — were treated with a larger degree of leniency. Wisconsin Latinos were especially affronted when INS officials initiated a series of deportation raids throughout the state during National Hispanic Heritage Week in 1983. These actions prompted Mexican American leaders to contact Governor Tony Earl to demand that he intervene against roundups that were “worse than a slap in the face” to the community.

Latinos in Wisconsin publicly decried these ongoing raids as unmerited and discriminatory, and rejected claims that undocumented immigrants were a drain on American society or that they were stealing jobs from American citizens. Study after study showed that undocumented workers worked longer hours for less pay than American citizens in comparable jobs, while paying more in taxes and wage deductions than they received in social services. Many employers bypassed federal minimum wage laws by paying undocumented workers outside of the U.S. tax system.

One undocumented farm laborer working in the state explained to a Milwaukee Journal reporter, “It’s not much money and it’s hard work. People in this country don’t work [for] that type of money. People here work eight hours and that’s it. If it wasn’t for us, the man’s vegetables would spoil and rot. That’s the truth.”

Another worker, employed sorting metals, understood that his lack of English skills and documentation status served as barriers to promotion: “I can’t defend myself or fight back, so I just work in silence. But I can see that I’ll be doing the same job as long as I remain here.”

Rising rates of immigration and reports of employer abuses against undocumented workers led federal legislators to debate the breadth and inclusivity of immigration reform throughout the early 1980s.

In 1986, Congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act, signed into law by President Ronald Reagan. This major revision of federal law sought to curb undocumented immigration by increasing border security and strengthening employer sanctions for knowingly hiring undocumented workers. But it also created a pathway to legalized status for people already living in the country without documentation. The legalization provision allowed undocumented immigrants who had lived in the United States since before Jan. 1, 1982, to receive temporary resident status and eventually work toward citizenship. Nationwide, approximately four million undocumented immigrants applied for legalization through the newly created pathway before the decade’s end.

In Wisconsin, social service and religious organizations such as Catholic Social Services, the International Institute, and La Casa de Esperanza set up aid centers to help undocumented people apply for legal status. Staff and volunteers counseled immigrants on the preregistration process and helped them fill out the necessary paperwork. These organizations also served as buffers between the undocumented community and INS officials, as many immigrants remained wary of interacting with agents of the federal government after the deportation raids of the early 1980s.

Fears within the undocumented community of continued government surveillance and possible deportation prevented many from applying for legalization. While officials estimated that more than twelve thousand people could be eligible for relief, fewer than a third actually applied through the federal government.

Yolanda Ayubi, a project coordinator at the Social Development Commission and a member of the Milwaukee Hispanic Coalition, explained, “There is a deep fear. It’s hard for a person who has always been hiding his tracks — using another name or social security number — to go and uncover everything that’s been covered.”

While popular media coverage focused on the uptick in undocumented immigration throughout the period, the majority of growth within Wisconsin’s Mexican-descent community in fact came from its American-born population.

According to the 1980 census, Wisconsin’s Latino population had grown to sixty-three thousand people, or about 1.3 percent of the state, 65 percent of which claimed Mexican descent. Three-quarters of Wisconsinites were born in the U.S., while more than 80 percent of Mexicans were born stateside. This population was comparatively younger than the general population; while 33 percent of the state’s population was under twenty years old, that number grew to more than 50 percent within the Mexican community.

In Milwaukee — a city that trailed only Chicago and Detroit in the Midwest with regard to Latino population — a 1983 survey conducted by the Milwaukee Journal found that more Latinos living in the city had grown up in the metro area than in Mexico. A third of all Latinos interviewed were in fact native Wisconsinites, while many had moved to Wisconsin as children.

These Mexican Americans who had lived their whole — or close to their whole — lives as Americans were more likely than their forebears to be bilingual and educated, having benefited from the reforms that gave them improved access to the public school system and university educations. While still facing discrimination in schools and workplaces, many were able to find work in a variety of professions, from entrepreneurs to educators, positioning them to be better advocates for newer immigrants.

This item was excerpted from Mexicans in Wisconsin, published by Wisconsin Historical Society Press. The book’s author, Sergio M. Gonzu00e1lez, was interviewed about the experiences of Mexican-Americans in the Badger State on the Dec. 25, 2017 edition of Wisconsin Public Radio’s Central Time.

Author Sergio M. Gonzu00e1lez is a doctoral candidate in the University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of History with research interests in American labor, immigration and working class history. His research investigates Milwaukee’s Latino community throughout the 20th century, focusing on the role of religion in creating interethnic and intraethnic communities, organizations and social justice movements.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us