How Our Elections Analysis Became A Supreme Court Question

Wisconsin is at the center of what is shaping up to be a landmark legal decision about how electoral districts are determined and the role of partisanship in creating legislative district boundaries.

September 28, 2017

Supreme Court of the United States building entrance

Wisconsin is at the center of what is shaping up to be a landmark legal decision about how electoral districts are determined and the role of partisanship in creating legislative district boundaries. As Americans increasingly tend to live among neighbors who hold similar political perspectives, the redistricting process is taking on new importance in a closely divided nation.

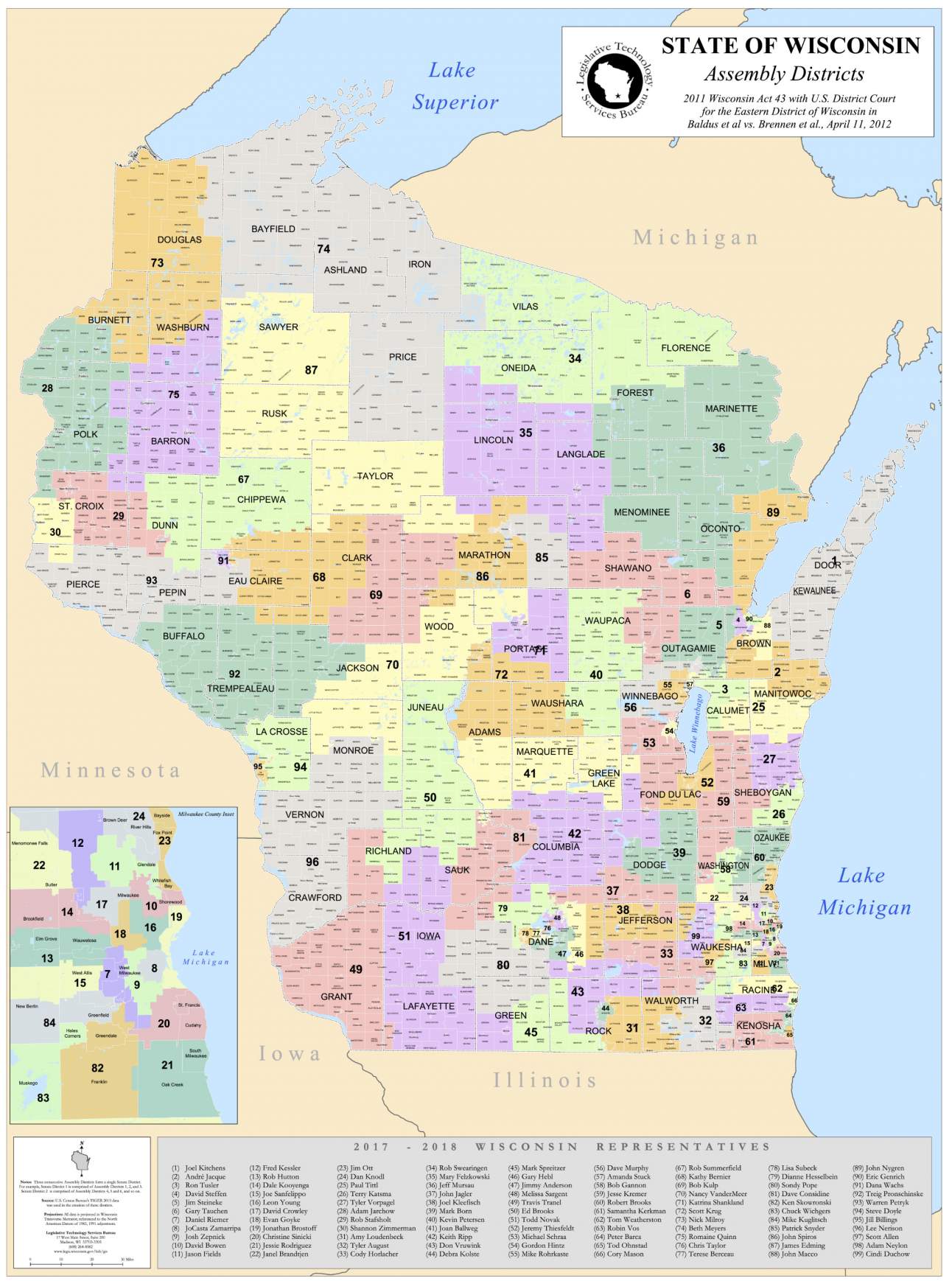

In its October 2017 term, the Supreme Court of the United States will hear arguments in Gill v. Whitford, in which the plaintiffs claim that the boundaries of Wisconsin State Assembly districts are a partisan gerrymander favoring Republican candidates. Gerrymandering is a term used to describe legislative districts that are intentionally shaped to steer election results, such that the outcome of elections are influenced by the selection of which voters are included within district boundaries.

In Gill v. Whitford, the plaintiffs argue that when Wisconsin’s Republican majority and a law firm it hired created legislative districts following the 2010 decennial census, they intentionally drew boundaries that ensured a continued GOP majority in the Assembly, the lower house of the state legislature. Though the plaintiffs are not directly challenging the state Senate district boundaries, they are implicitly involved in the case because they are based on the Assembly districts. This lawsuit is not challenging the state’s eight Congressional districts.

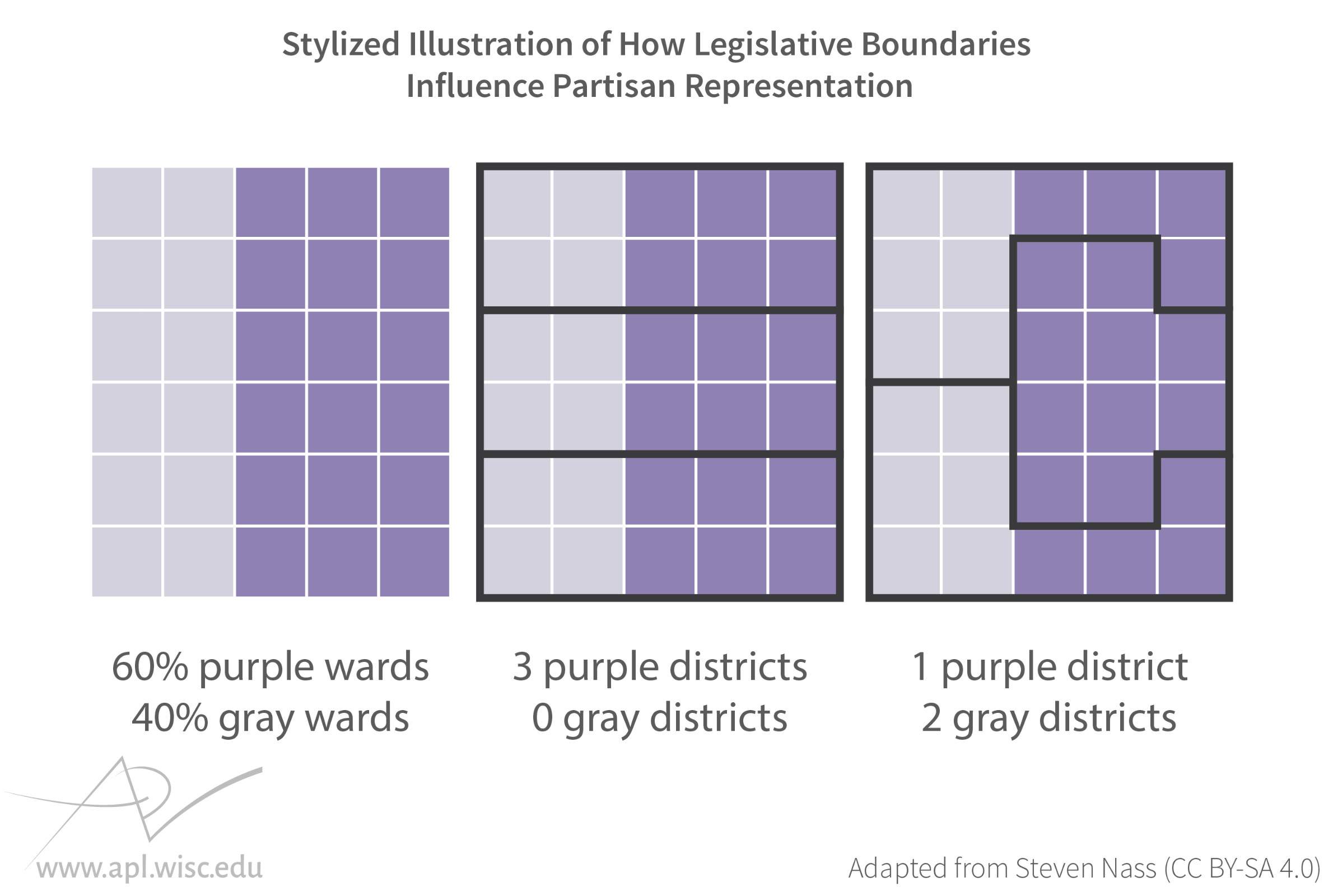

Gerrymandering is generally achieved through two processes, known colloquially as “cracking” and “packing.”

In the case of a partisan gerrymander, cracking refers to the practice of the controlling party setting district boundaries that split geographic concentrations of opposing party voters across multiple districts so that these constituents are not able amass enough votes to win a seat in a given district. Packing refers to the practice of drawing districts to include as many opposing party voters as possible, guaranteeing that the opposing party will win a selected few seats by a deep margin, but allowing neighboring districts to remain safely in the controlling party’s hands.

The plaintiffs in Gill v. Whitford claim that the Republican majority in Wisconsin’s state legislature applied both cracking and packing in its 2011 redistricting process, setting new state Assembly district boundaries in order to ensure their continued dominance in the state legislature.

Historical analysis cited in Supreme Court brief

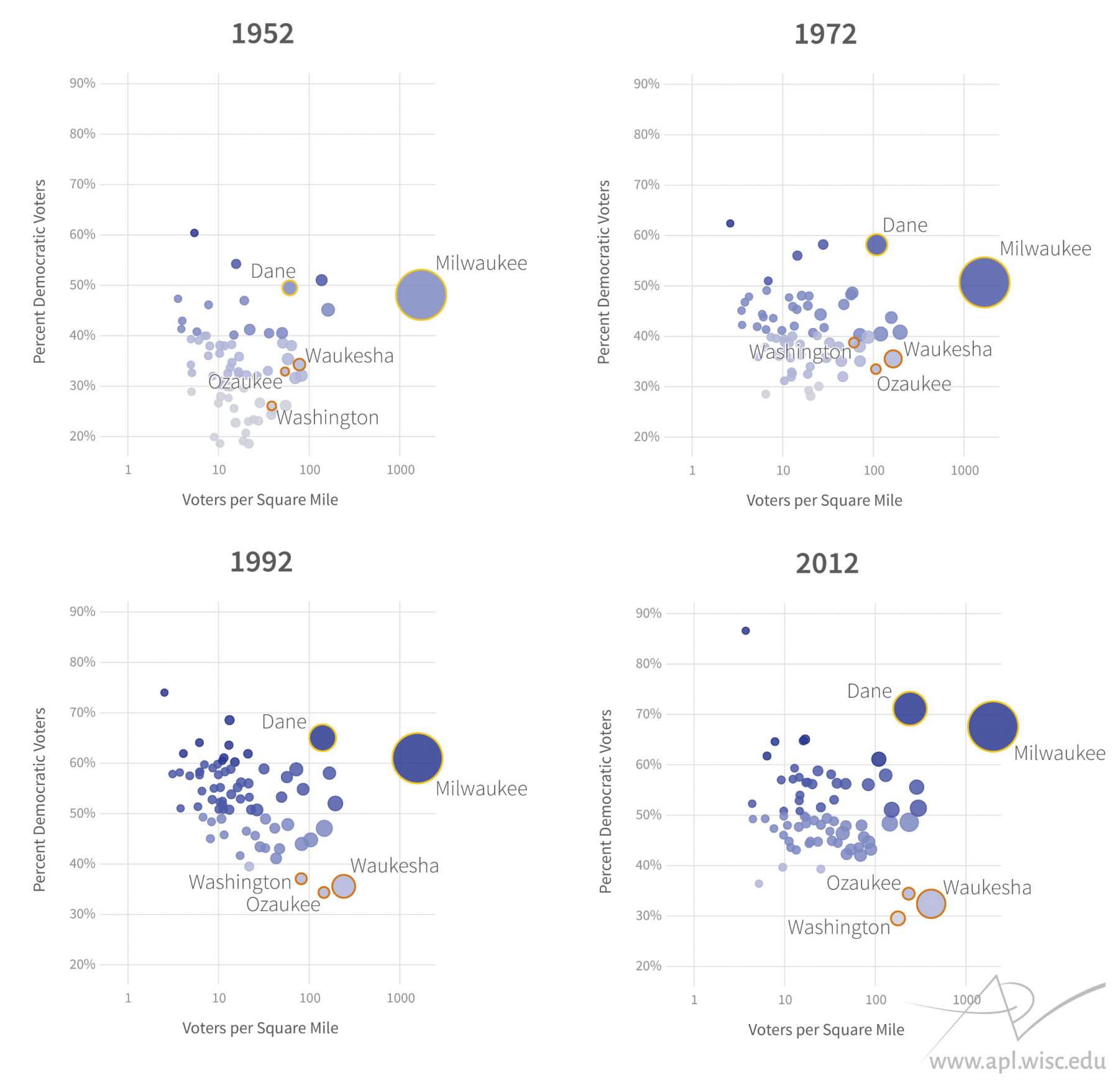

The Republican National Committee and National Republican Congressional Committee argued in an amicus curiae brief filed with the Supreme Court on April 24, 2017 that the concentration of Democratic voters into urban districts is a natural process related to demographic change. It stated: “Democratic voters are more likely to be packed into compact and homogeneous areas not only in Wisconsin, but also in most of the rest of the United States.”

In support of its argument, the RNC brief cited a WisContext report that discussed analysis by the University of Wisconsin Applied Population Laboratory of county-level partisan voting patterns in the 1952, 1972, 1992 and 2012 presidential elections in Wisconsin. This research showed that Democratic voters were increasingly concentrated in high population density counties.

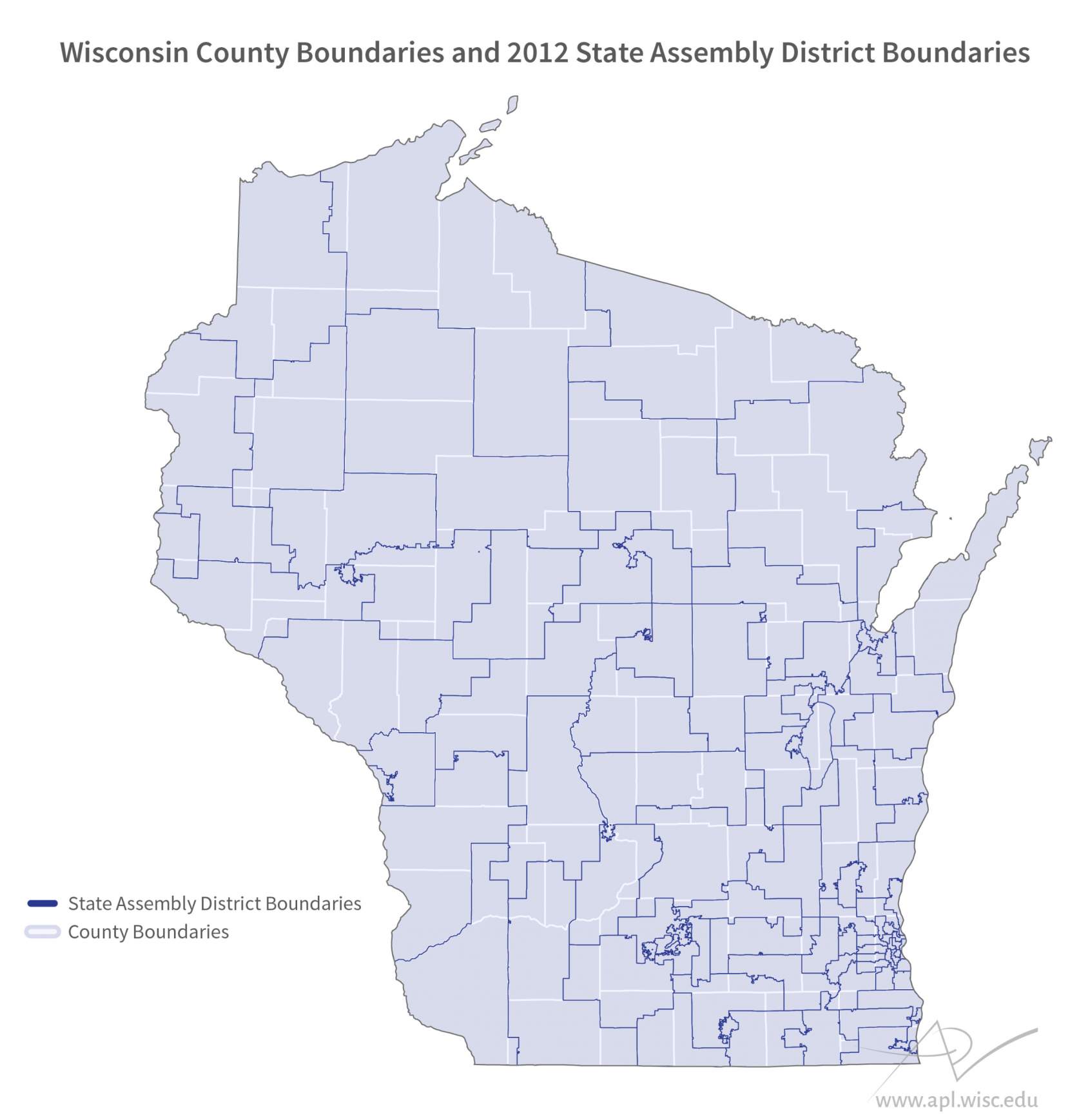

However, it is important to distinguish between counties and legislative districts because these two geographies are not equivalent. Concentrated partisanship at one scale does not make partisanship at the other inevitable. Legislative districts are redrawn every 10 years in order to account for population change. The linchpin of legislative districting, known as the “one person, one vote rule,” requires that district boundaries be redrawn periodically so that each person has roughly equal representative power in government.

As Wisconsin’s population grows and is redistributed through the demographic forces of births, deaths and migration, it means legislative districts must be changed over time to maintain equality in representation.

For example, a long-standing Wisconsin population trend sees urban populations growing while more rural parts of the state remain the same or even decrease in population. Without periodic redistricting, more and more residents of densely populated areas would share representatives in the state legislature, while people in places with static or shrinking populations would have an increasingly larger proportion of representation.

Just how different are counties and legislative districts in Wisconsin? The following map shows Wisconsin’s 72 counties overlaid with the state Assembly districts set in the 2011 redistricting process. The relatively smaller in geographic area districts in major cities like Madison, Milwaukee and Green Bay reflect higher population density in those places. In less densely settled regions, meanwhile, a single elected official might represent voters who live in several counties.

Redistricting is meant to equalize the share of representation across parts of the state as populations shift. Applying the one person, one vote rule means that as population density within a district increases, its geographic size must become smaller to maintain equal representation.

On the other hand, county boundaries do not change in response to changing populations. In 1950, the population density of Milwaukee County was 732 persons per square mile. In 2010, it was about 800 persons per square mile.

The following chart shows the population density for Milwaukee County, Jefferson County and Price County since Wisconsin’s founding. These three counties have different demographic trajectories, and their county boundaries have remained fixed even though their populations have shifted. Milwaukee County’s population density has increased dramatically over time, so one would expect there to be major changes to political districts within Milwaukee County.

Urban counties in Wisconsin have increasingly leaned more towards Democratic Party candidates over the past half-century, but county boundaries, unlike those for legislative districts, are typically fixed over time and are not at risk of manipulation for political purposes.

In Gill v. Whitford, the Supreme Court is reviewing whether legislative district boundaries were intentionally altered to promote continued Republican control of the State Assembly. An increase in voters in urban counties who support Democrats may lead to urban legislative districts with very high concentrations of Democratic-leaning voters, or what could be considered as natural “packing” in these most densely populated districts. But that doesn’t rule out the possibility that the boundaries were created to produce even more packing than can be accounted for by demographic processes.

To address whether concentration of Democratic voters is the result of underlying demographic shifts as well as consider possible district cracking in Wisconsin, the Supreme Court will review a new metric of gerrymandering put forth by the plaintiffs in Gill v. Whitford. Called the efficiency gap, it measures the difference in a state between the number of votes cast in favor of a party candidate and the number of seats won by that party. Under this metric, the balance of seats in each of Wisconsin’s two state-level legislative bodies and its eight seats in the U.S. House of Representatives should be roughly equivalent to the partisan balance of votes statewide — regardless of underlying demographic processes.

The RNC and NRCC brief argued against using the efficiency gap as a metric of gerrymandering: “In light of this general trend, which results in an ‘inefficient’ concentration of Democratic votes in densely populated areas, the [efficiency gap] is a tool that advances the partisan interests of the Democratic Party.”

Constant demographic flux leads to a need for periodic redistricting to ensure continued equal representation in government. The founders of the United States recognized the crucial role of demographic change in a representative government when they drafted the U.S. Constitution. Article 1, Section 2 requires that a population census will be taken every 10 years. Wisconsin’s state constitution likewise calls for revising state legislative district boundaries following each decennial federal census to maintain equal representation amid a changing population.

The core questions in Gill v. Whitford are who controls that process and how it might be manipulated to the benefit of one party over another. With the 2020 census and another redistricting cycle approaching, the case is attracting considerable national attention and has the potential to set a major precedent.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us