History Is at the Heart of Wisconsin's 2021 State of the Tribes Address

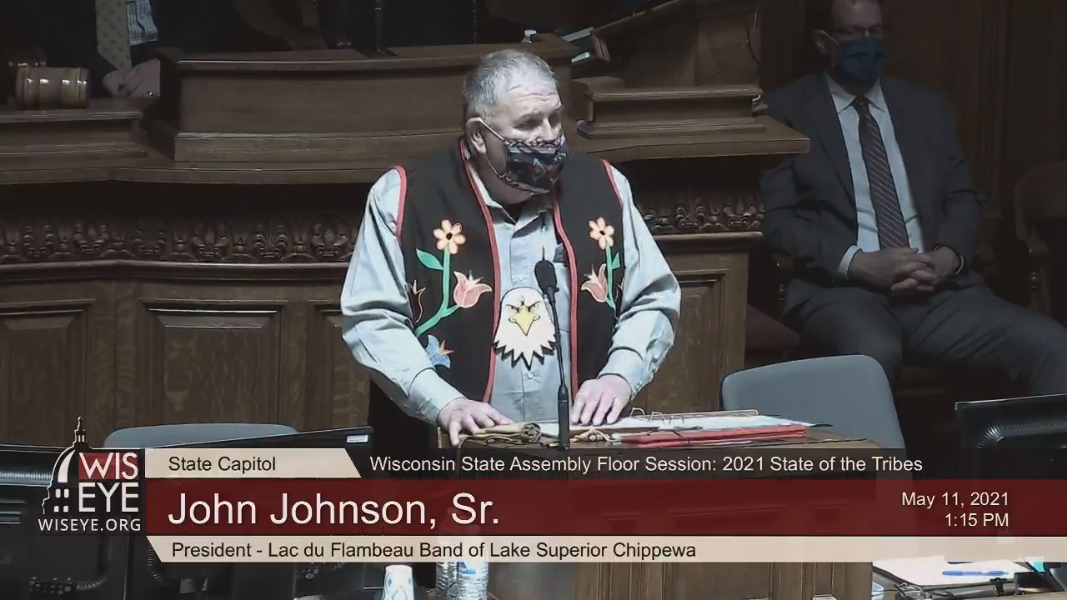

In a speech to the state Legislature, Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa President John D. Johnson, Sr. connects the principles of tribal sovereignty to contemporary issues important to Native communities.

May 11, 2021

History’s deep currents and their inexorable flows into present-day conditions flowed throughout the 2021 State of the Tribes address, delivered to the Wisconsin Legislature on behalf of Wisconsin’s 11 sovereign and federally recognized tribal nations. At the same time, the history-making magnitude of the coronavirus pandemic loomed over the speech and its setting.

The address was delivered by John D. Johnson, Sr., president of the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, whose 12-by-12-mile reservation — or Waswagoning, a “place where they fish by torchlight” in the Ojibwe language — now straddles portions of Iron, Oneida and Vilas counties. “Just travel north to Minocqua and hang a left,” said Johnson, inviting lawmakers to visit.

Johnson sketched an overview of the relationship between tribal nations and the state government, flowing from Native rights confirmed in treaties with the federal government since before Wisconsin joined the Union. Now nearly two centuries later, the treaties’ cultural and legal consequences inform both daily life and long-term issues in Native communities. From remembrance of the Sandy Lake Tragedy to the legacy of the bald eagle “Old Abe” to memories of the “Wisconsin Walleye War” and its lingering tensions, Johnson connected past and present to illustrate issues important to Wisconsin’s Native peoples.

The speech marked the 17th annual State of the Tribes address. The Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Council selects a leader from one of Wisconsin’s tribal nations to communicate concerns and priorities with lawmakers.

Early in the address, Johnson called for a moment of silence to remember those who have been lost during the pandemic. COVID-19 has hit Native communities particularly hard across the nation, including in Wisconsin, resulting in broad disparities among different racial and ethnic groups tracked by public health authorities.

As of May 10, the 95 confirmed deaths among American Indian Wisconsinites make for the highest COVID-19 mortality rate in the state by race or ethnicity, more than 50% higher than white residents and more than 35% higher than Black residents. The disparity in hospitalization rates is similarly wide, with American Indian Wisconsinites more than twice as likely as white residents to be admitted for treatment following a diagnosis, a level barely behind that for Black residents. In terms of confirmed cases, American Indian Wisconsinites are about 40% more likely to be infected than white residents, though about 80% as likely as Hispanic residents, who have the state’s highest rate.

“The pandemic has hit hard the most vulnerable people,” said Johnson, who wore a mask throughout the speech. “This includes our elders and those with susceptible health conditions within our communities.”

Johnson highlighted the opioid epidemic and a parallel problem of methamphetamine addiction throughout northern Wisconsin that has continued during the global health crisis.

“The flow of drugs into the Northwoods has escalated during the pandemic as mental health, economic and social challenges exert growing pressure on people and families,” he said.

To confront that issue, Johnson endorsed a state budget proposal put forth by Gov. Tony Evers that would fund a regional medical facility to provide mental healthcare and addiction treatment. He also noted the continual barrage of mass shootings across the United States, including a May 1 shooting at the Oneida Casino in Ashwaubenon, as more impetus for prioritizing mental health.

The economic impacts of tribal gaming in Wisconsin’s Native communities and surrounding areas was the first of several examples Johnson raised to address misconceptions about governance and sovereignty. Pointing to the origins of the Lac du Flambeau name, he discussed Native spearfishing and netting practices, explaining how the annual harvest is gathered and used, and decrying continuing harassment, threats and assaults faced by people exercising their tribal rights.

“This spearing season, we provided fish to Elders in our community and others who struggled to eat during the pandemic,” said Johnson. “We harvest fish, hunt deer and gather wild rice and other foods dependent on a healthy ecosystem.”

Johnson described the cultural role and longevity of these rights.

As chair of the Voigt Intertribal Task Force committee, Johnson plays a role in policy recommendations regarding natural resources and treaty rights to the board of commissioners for the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission.

How natural resources are important to Wisconsin’s tribal cultures and livelihoods was emphasized by Johnson, who advocated development guided by a long-term prioritization of sustainability. As such, Johnson condemned mining, citing the Flambeau Mine, an open-pit gold and copper mine in Rusk County that operated in the 1990s and was the focus of intense controversy and legal battles — it has since been the focus of a reclamation process.

“We ask how our decisions today impact those who come after us hundreds of years from now,” Johnson said. “We respectfully ask every level of state government to do the same.”

Johnson noted and denounced bigotry that Wisconsin’s Native communities have endured and continue to confront.

To challenge systemic racism and discrimination, Johnson called for continuing investment in education. He cited the example of Act 31 and its requirements that Native culture and history are taught in Wisconsin schools. (PBS Wisconsin is a partner in crafting the Wisconsin First Nations curriculum.) He also noted the April 2021 passage and enactment of Senate Bill 69, which sets requirements for teaching about the Holocaust and other genocides.

Praising those goals, Johnson said he hopes this new law will also mean students learn about genocide perpetrated upon Native peoples.

Concluding the address, Johnson discussed efforts to change derogatory place names and offensive sports mascots. He highlighted the approval of a new name for a lake in western Oneida and Vilas counties.

Johnson connected dehumanizing language experienced by Native people to the ongoing crisis of murdered and missing Indigenous women.

May 5 marked MMIW Awareness Day, which was recognized by tribal councils and over a dozen local government bodies around the state. In July 2020, Wisconsin Attorney General Josh Kaul convened a Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women task force for the state. The group subsequently held its first meeting in December, and identified a lack of data about the scope of this issue as an immediate priority. The state has received $300,000 from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Violence Against Women Act grant program, with $200,000 being dedicated to a research project to understand how many Native women in the state suffer these crimes.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us