Health Officials Begin to See Flattened Curve

The governor and public health officials expressed cautious optimism in a Monday briefing.

April 13, 2020

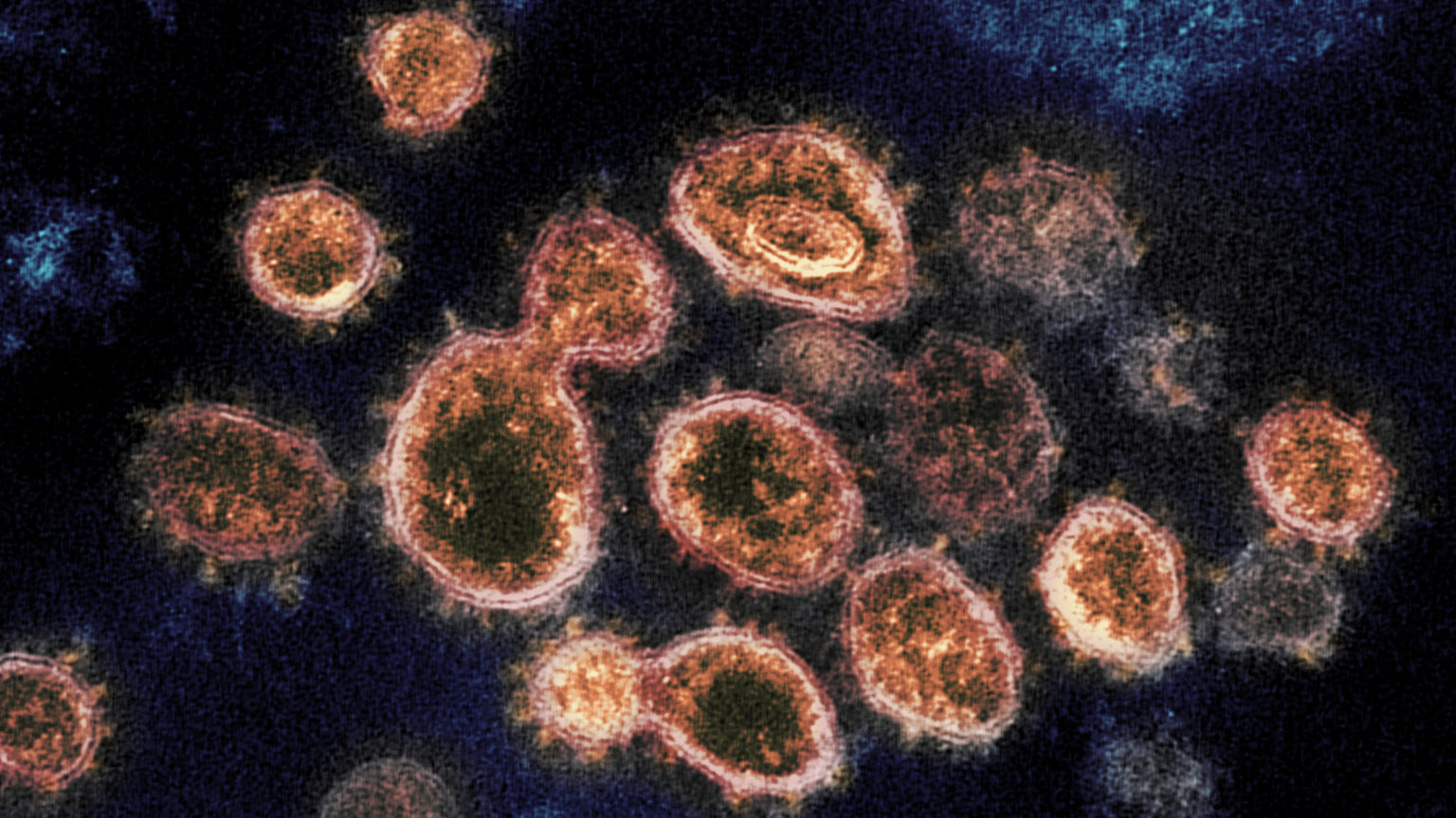

This transmission electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, isolated from a patient in the U.S. Virus particles are shown emerging from the surface of cells cultured in the lab. The spikes on the outer edge of the virus particles give coronaviruses their name, crown-like. (Courtesy: NIAID-RML)

Wisconsin is starting to see a flattening of its epidemic curve, the governor said at a Monday briefing.

He and public health officials cautioned Wisconsinites that though the curve is flattening, the state is not “out of the woods” yet.

“It doesn’t mean that we’ve eradicated or eliminated–we’ve flattened the curve, but we haven’t smashed the curve down to nothing,” state epidemiologist Dr. Ryan Westergaard said. “There’s still people with the infection in the community that we don’t know about. So we need to be very careful, make sure we have all the resources in place.”

Gov. Tony Evers said the state’s “Safer at Home” policy was key to help tamp down the number of cases.

“We’re talking about fewer people getting sick, we’re talking about less of an impact on our health care systems, we’re talking about saving lives, we’re talking about your neighbors and coworkers and friends and family,” Evers said. “These are the lives we will save if we continue to flatten the curve.”

As the state sees a reduction in an increase of cases, the governor said he will be “very careful” on the decision to open the state. He and health officials at the briefing said public health measures like increased testing and contact tracing capacity would be needed to allow for a loosening of the stay-at-home order.

“We’re not going to be flipping a switch,” Evers said.

This comes the same week the Legislature is set to take up a bill to provide the state with coronavirus-related aid. Evers said he had not seen the legislation and could not comment on it.

Evers did criticize legislative Republicans and state and federal courts for allowing last Tuesday’s election to move forward with in-person voting. He called it “a mess that could’ve been avoided.”

“I don’t know what I could have done differently–the Supreme Court has decided that it was unconstitutional for me unilaterally to [change the election],” Evers said. “If I had done that earlier, the result would have been the same. They would have turned it down five weeks before that.”

Westergaard said in terms of the medical impact the in-person election could have had on the state’s efforts to combat COVID-19, health officials should know one-to-two weeks after the election, or likely in the coming days.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us