Evictions in Wisconsin Dipped During a Federal Moratorium — What's Next for Renters and Landlords?

Here & Now extra: A nationwide halt on evicting tenants during the pandemic simultaneously slowed down and uncovered deeper fissures in a housing crisis faced by lower-income renters.

By Marisa Wojcik | Here & Now

August 3, 2021 • Northeast Region

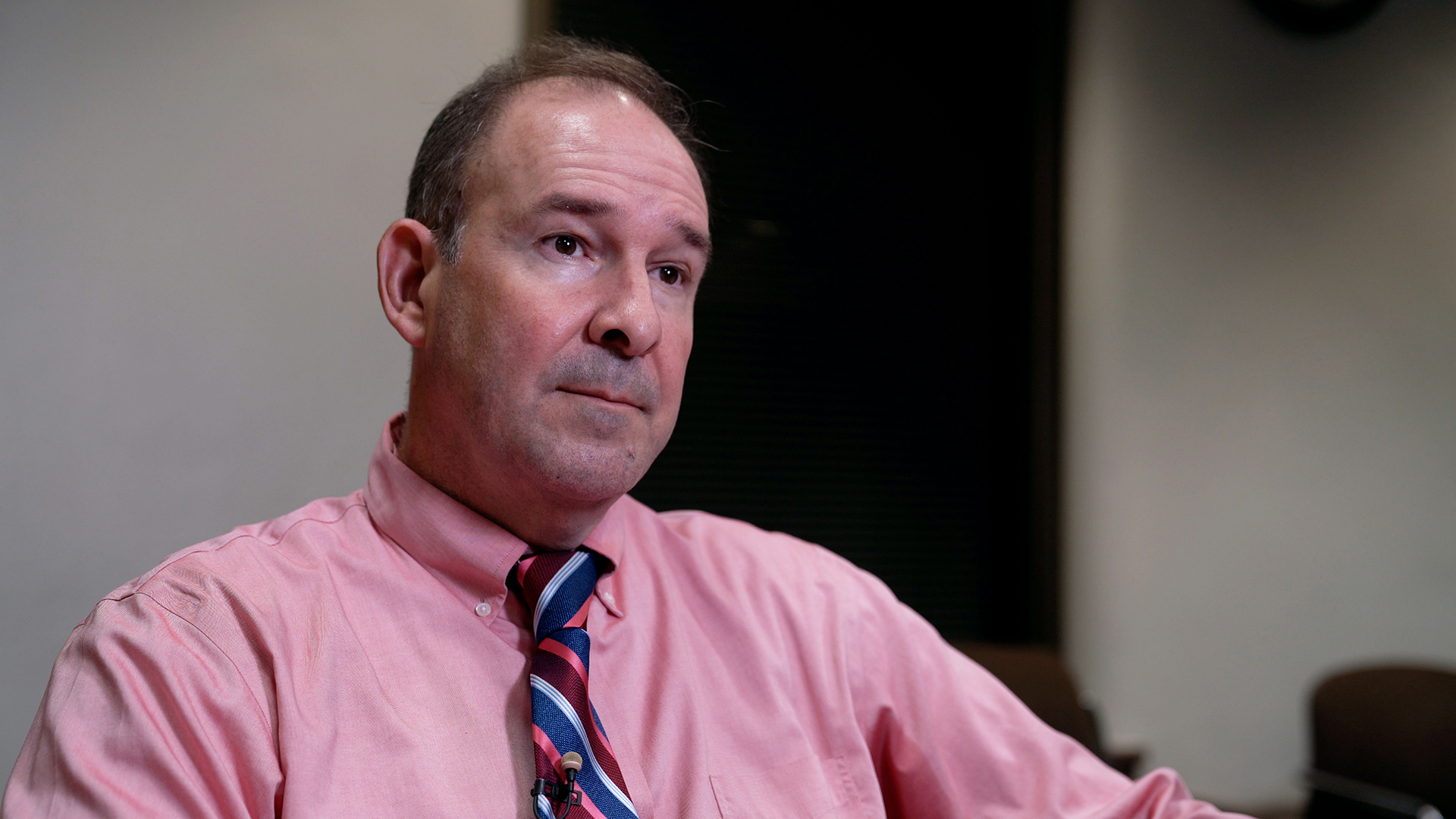

Brown County Commissioner Paul Burke presides over an eviction hearing in July 2021. (Credit: Marisa Wojcik / PBS Wisconsin)

On a Tuesday afternoon, a small crowd of people gather around the door to Commissioners Courtroom B at the Brown County Courthouse in downtown Green Bay. Landlords, renters and attorneys wait to have their eviction cases heard.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, this crowd has been much smaller as landlords were prohibited from evicting tenants for not paying rent.

A federal moratorium on evictions was declared Sept. 4, 2020 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to slow the spread of COVID-19. After multiple extensions, the moratorium expired July 31, 2021.

Like many unexpected developments over the course of the pandemic, this nationwide ban on evictions was unprecedented. As a result, the impacts of ending that ban are yet another unknown.

“We expect to be very overwhelmed. We’re already getting an increase in housing calls,” said J. Scott Schnurer, a housing lawyer based in Green Bay with Legal Action of Wisconsin.

The statewide legal services nonprofit has been planning for different worst-case scenarios following the end of the moratorium, knowing that landlords will once again be able to evict tenants for non-payment of rent, meaning a surge of evictions could follow.

“Our firm-wide housing unit has been meeting on a regular basis to come up with a pattern and practice to try and serve as many people as we can,” Schnurer said.

In his more than 15 years in this work, Schnurer tries to represent as many clients facing eviction as possible when they reach out for help no matter where they are in the process, even if it is only an hour before a court date.

Eviction proceedings for people who live in Brown County are conducted at the courthouse in downtown Green Bay. (Credit: Marisa Wojcik / PBS Wisconsin)

Eviction cases can range from non-renewal of a lease to violations such as property damage, chronic nuisance or police calls, or too many people living in one unit, according to Schnurer. However, the primary reason for eviction is for not paying rent.

“I’d say 90% of what we generally see are for nonpayment issues,” said Brown County Commissioner Paul Burke, who has all eviction cases come before him when a tenant is first summoned.

Burke will ask the tenant questions to ensure the landlord has followed appropriate legal steps. He also tries to ask the tenant if they have a legal defense for not granting an eviction.

“I will ask some questions, but it’s not my job to present a defense,” Burke said.

Brown County Commissioner Paul Burke, who is responsible for adjudicating eviction hearings, notes landlords pursue orders due to non-payment of rent in the vast majority of cases. (Credit: Marisa Wojcik / PBS Wisconsin)

It’s not uncommon for the tenant to give an explanation as to why they’re behind in their rent payments, like losing a job or covering expensive medical bills.

“They’re very surprised when I tell them that’s not a defense to these sorts of actions,” said Burke. “Especially when you have nonpayment outside of this moratorium time, to get an eviction is not a difficult process.”

Danielle Kasee found out just how easy it is to be evicted for nonpayment during a three-month lapse in the eviction moratorium. On her daughter’s 16th birthday on July 31, 2020, Danielle and her children lost their home. Exactly one year later, the day the federal moratorium expired, Kasee got to make it up to her daughter for her 17th birthday.

The crisis of losing housing

Before the moratorium, a landlord would seek an eviction order based on nonpayment rather than lease violations because it was a more clear-cut process in the legal system. During the moratorium, though, landlords found other avenues that were less certain to result in an eviction.

Beyond not knowing what legal defenses they might have, renters also may not understand the overall eviction process. Some don’t appear in court, meaning a judgement defaults to eviction. Others move out after only receiving a warning.

“Sometimes you get these notices and it scares the tenant enough and they vacate rather than dispute the case and assert their rights,” said housing lawyer J. Scott Schnurer.

If either party in an eviction proceeding is likely to have an attorney, it’s the landlord. In Schnurer’s experience, this difference creates an imbalance when an eviction case is heard before a commissioner or a judge.

“Landlords and tenants are not on equal footing for negotiating,” Schnurer said. “Tenants would have a much better position if they had representation.”

Moreover, if a tenant is behind in rent, it’s unlikely they can afford an attorney.

Renters may not be familiar with the eviction process, which includes a timeline of official notices and hearings. (Credit: Marisa Wojcik / PBS Wisconsin)

Much of the legal process of an eviction is unknown territory for a tenant, whereas some landlords that own many properties pursue it regularly. Meanwhile, even just standing before a judge can be scary for a tenant.

“It’s intimidating to be in a courtroom when you’re not used to being in a courtroom,” said Schnurer.

Milwaukee County is attempting to address that issue with a program called “Right to Counsel.” The pilot program will guarantee residents earning less than 200% of the federal poverty level free legal services for eviction proceedings.

Schnurer said there are a lot of unknowns and misconceptions related to evictions, particularly for people who haven’t experienced them.

“The process happens much quicker than the 10 days that people see on this piece of paper because they misunderstand that it’s not directed to them as the tenant. It’s directed to the sheriff,” Schnurer said. “If you get evicted and the sheriff has to assist the landlord in removing you, you’re going to get whatever you can carry out with you at the moment and the landlord can just get rid of the property left over.”

Deputy Joseph Fischer of the Brown County Sheriff’s Office handles most evictions once they get to the point where a tenant must be physically removed. He tries to connect them with social services so they’re not just out on the street.

“When someone truly does need help, I don’t want to be the person to just remove them. I want to at least give them some sort of direction if they’re willing to take it,” he said.

Deputy Joseph Fischer works with the Support Services Division of the Brown County Sheriff’s Office, which becomes involved in eviction process when an order authorizes removal of tenants from a rental property. (Credit: Marisa Wojcik / PBS Wisconsin)

Over his 10 years as a civil process deputy, Fischer has seen the number of evictions steadily rise and involve an increasing number of people who are elderly or who have mental health issues.

“He’s built up relationships and can work together with different agencies,” said Capt. John Rousseau, who leads the Brown County Sheriff’s Office Support Services Division.

“This process is tough,” explained Rousseau. “From the sheriff’s office perspective and from our position, we’re enforcing the order of the court. We have a very, very small piece at the very, very end. And the unfortunate part is when our civil process deputies go out there, while we only have this very last part, everything else comes along with it, too. So the emotion and the stress and the fact that they’re going through a crisis of losing their housing. All of that comes out at the very last step.”

The landlord’s role in evictions

Landlord Joe DeKeyser owns six rental properties in Green Bay, which house a total of nine households. As a smaller landlord, the eviction process is expensive and as foreign to him as it is to most tenants.

DeKeyser said he has compassion for his renters, some of which have a prior eviction on their record or are living on fixed incomes.

“For me, to give them an opportunity as a starting base, it meant a lot that they could build from there and have some stability to go forward,” he said.

Joe DeKeyser owns six rental properties in Green Bay, and has been a landlord for nine years. (Credit: Marisa Wojcik / PBS Wisconsin)

When the pandemic upended some tenants’ lives, DeKeyser worked with them as they secured federal emergency rental assistance funds distributed through local community action programs.

During his nine years as a landlord, DeKeyser said he’s only evicted one tenant for nonpayment when all other options ran out.

“We very much empathized with her, but the situation was not going to change and we couldn’t see how we could help her in any way,” he said.

As much as DeKeyser empathizes with tenants, he hopes they understand his perspective.

“The expenses of insurance, utilities, upkeep and then the mortgage on top of it — it really puts a squeeze on the bottom of that line,” DeKeyser said.

Joe DeKeyer, a landlord in Green Bay, stops by one of his rental properties in Green Bay. (Credit: Marisa Wojcik / PBS Wisconsin)

When DeKeyser gives tenants a chance to catch up on rent, that’s money out of his own pocket to pay for personal expenses. But he still sees eviction as a “last resort.”

“I think the pandemic really showed the disconnect in communications between landlords and tenants,” said J. Scott Schnurer. “I think that there’s this mentality that you just don’t communicate until it’s almost too late.”

The story can look very different for landlords that own a lot of properties, where evicting lower-income tenants can be profitable, said Branden DuPont, a data analyst with the Medical College of Wisconsin.

DuPont’s work has focused on Milwaukee, where he’s built a system to reliably track eviction data to study trends and better understand their impacts on people’s health. He considers the eviction process at a broad level.

“It’s really used as a rent collection tool,” DuPont said. “If you have 70% of your income going to rent and you have a large shock – your car breaks down or maybe your kid has some sort of emergency, maybe they break their arm – you have this decision because you’re already overextended financially. Do I pay my landlord? Or do I pay to fix my car so I can get to work? Or this medical bill because my kid broke his arm? What the serial eviction practice is doing is trying to re-prioritize who gets paid first.”

A housing attorney sits in a largely empty courtroom at the Brown County Courthouse, which has seen fewer eviction proceedings while a nationwide moratorium was in place. (Credit: Marisa Wojcik / PBS Wisconsin)

With the federal moratorium in place, evictions still occurred but were significantly reduced in number.

There was a three-month gap in 2020 when no moratorium was in place. Across Wisconsin, there were 365 total eviction filings in May. That number shot up to 3,042 eviction filings for June when the moratorium lapsed, according to eviction data from the Department of Administration.

Overall, there were one-third fewer eviction filings statewide with the moratorium in place. In Milwaukee, eviction filings were cut nearly in half.

Eviction’s impacts on health

Branden DuPont’s work at the Medical College of Wisconsin is seeking to understand how evictions affect a person’s health.

“To be in good health, you need stable, reliable shelter first and foremost,” said DuPont. “There’s a lot of established research showing an association between evictions and a whole host of social determinants of health and the worst health outcomes.”

“You’re one and a half times more likely to die just overall compared to not having an eviction on your record,” noted DuPont.

Evictions due to nonpayment also compound the problem for renters with extremely low incomes.

“If they have an eviction on their record, the security deposits can go up. You have less options for where you can and who you can rent from,” said DuPont. “Typically, it’s lower-quality housing, you have to pay more and you need more money upfront.”

An apartment complex in Green Bay is home to lower income renters, who can see their difficulties finding housing grow if they have been evicted. (Credit: Marisa Wojcik / PBS Wisconsin)

The National Low Income Housing Coalition presents data about housing costs in Wisconsin, including how many hours a minimum wage worker would need to afford a fair market rate unit, how much of a person’s income goes to rent and the annual income needed to afford rent.

The pandemic has shined a brighter light on cracks that already existed in the housing system, but it also made those gaps wider.

“I think this has really revealed how fragile our housing system is for extremely low-income households,” said Brad Paul, executive director of the Wisconsin Community Action Program Association, the organization charged by the state to distribute federal emergency rental assistance dollars.

However, the issue of affordable housing is starting to expand beyond low-income renters.

“We’re seeing this entirely different demographic of people than we’ve ever served before,” said Cheryl Detrick, president and CEO of the Northeast Wisconsin Community Action Program, or NEWCAP. “They never qualified for any programs before. They never needed programs before.”

Cheryl Detrick is the president and CEO of the Northeast Wisconsin Community Action Program, also called NEWCAP, which is responsible for administering housing assistance in the Green Bay region. (Credit: Marisa Wojcik / PBS Wisconsin)

These emergency rental assistance dollars will continue to flow to renters and landlords through 2025, with or without a moratorium in place.

Housing advocates want to keep the moratorium in place as the more contagious Delta variant of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 rages across the country and is spreading rapidly in Wisconsin. But it’s also about maintaining stability.

“It would be very beneficial from where I sit to have the moratorium extended, particularly because there is a significant amount of money in the housing system right now that can help stabilize people, and that helps landlords too,” said Paul.

Advocates also fear that even with rental assistance dollars, the system will become overrun with new eviction filings.

Housing advocates have been seeking to extend the federal moratorium on evictions during the COVID-19 pandemic. (Credit: Marisa Wojcik / PBS Wisconsin)

Paul pointed to estimates that one in five households nationwide are behind in rent. As of July 5, 2021, the U.S. Census Household Pulse Survey estimated almost 78,000 people in Wisconsin live in households that are not caught up on rent.

In Wisconsin, the state Supreme Court ruled the governor and Department of Health Services cannot enact a statewide moratorium on evictions related to a public health emergency. Additionally, the state Legislature has banned municipalities from setting any local moratorium on evictions.

At the federal level, Democrats in Congress have sought to reinstate an eviction moratorium before it expired, which the administration of President Joe Biden indicated it did not have legal authority to enact. On August 3, the CDC was moving to institute a new eviction moratorium for places with high COVID-19 transmission, though details had not yet been announced.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us