A Lack Of Precedent In Wisconsin's Special Elections Lawsuit

If a voter in Wisconsin sues the state to try and compel the governor to call a special election, they might have a hard time finding precedent for that action.

By Scott Gordon

March 16, 2018

Wisconsin Capitol dome with special election lawsuit precedents text

If a voter in Wisconsin sues the state to try and compel the governor to call a special election, they might have a hard time finding precedent for that action. A plaintiff in such a case can make specific arguments about what state law requires a governor to do when a state legislative seat becomes vacant, and perhaps broader constitutional arguments about the right of citizens to elect their representatives.

But special-elections lawsuits are hard to find in Wisconsin’s legal history, and similar suits in other states have little to no bearing on how a judge should interpret Wisconsin law. On top of that limitation, federal courts haven’t really given state-level judges much to go on.

At the national level, U.S. Supreme Court justices and federal judges have written many times in rulings about the fundamental right of citizens to vote for their own representatives, but have created very little precedent that applies to the central question of Newton v. Walker: What do Wisconsin’s special-elections laws actually mean?

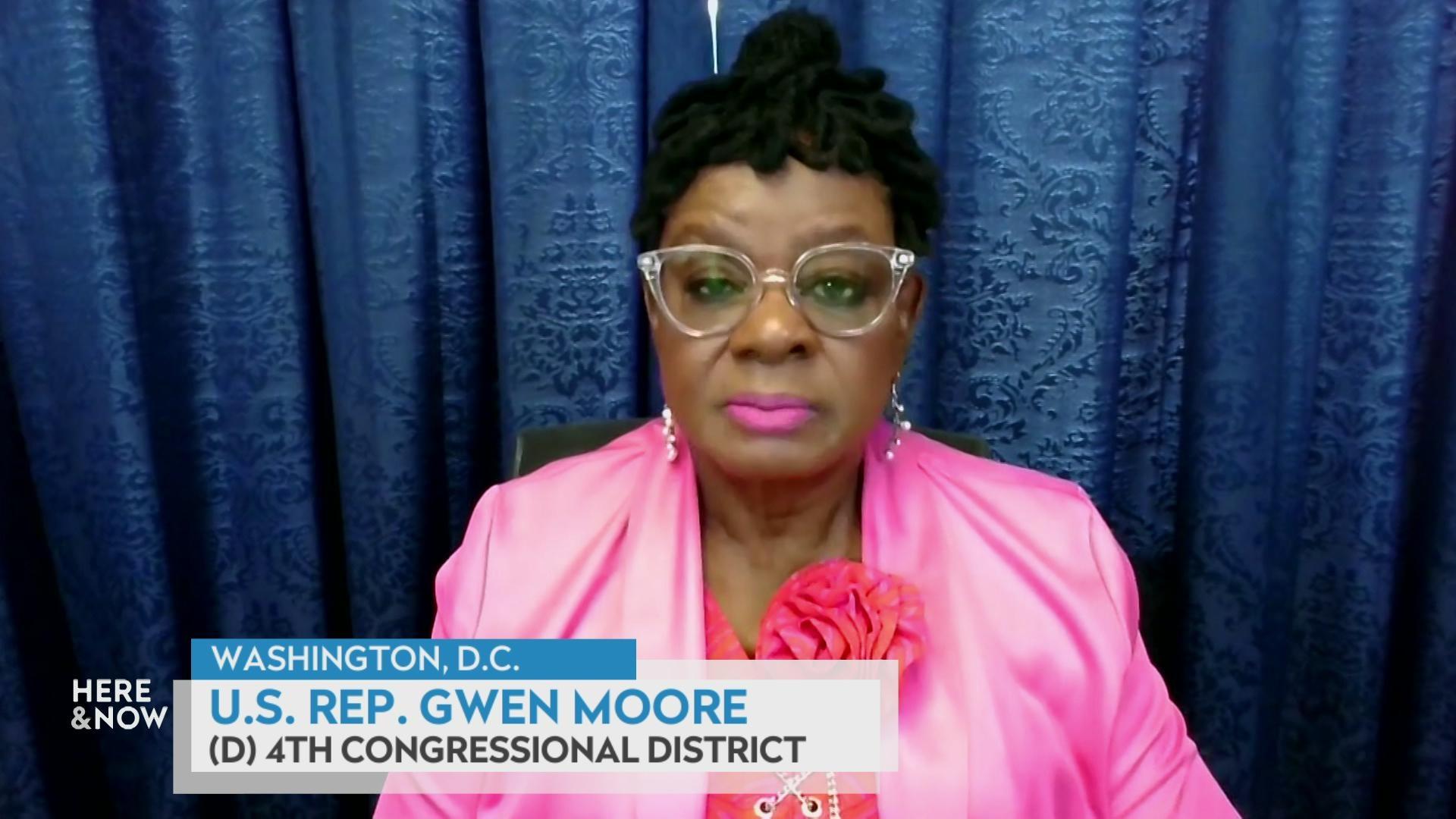

The case, filed in Dane County Circuit Court in late February, seeks to compel Gov. Scott Walker to call special elections in the state Legislature’s 1st Senate District and 42nd Assembly District. Both became vacant on December 29, 2017, when Walker hired their officeholders for posts in his administration.

The plaintiffs — five voters living in the vacant Assembly district, and three in the vacant state Senate district — contend that section 8.50 of Wisconsin’s state statutes plainly require the governor to call special elections. Walker and state Attorney General Brad Schimel have countered that the law’s language technically allows the governor to wait until the already regularly scheduled election for both districts, in November 2018.

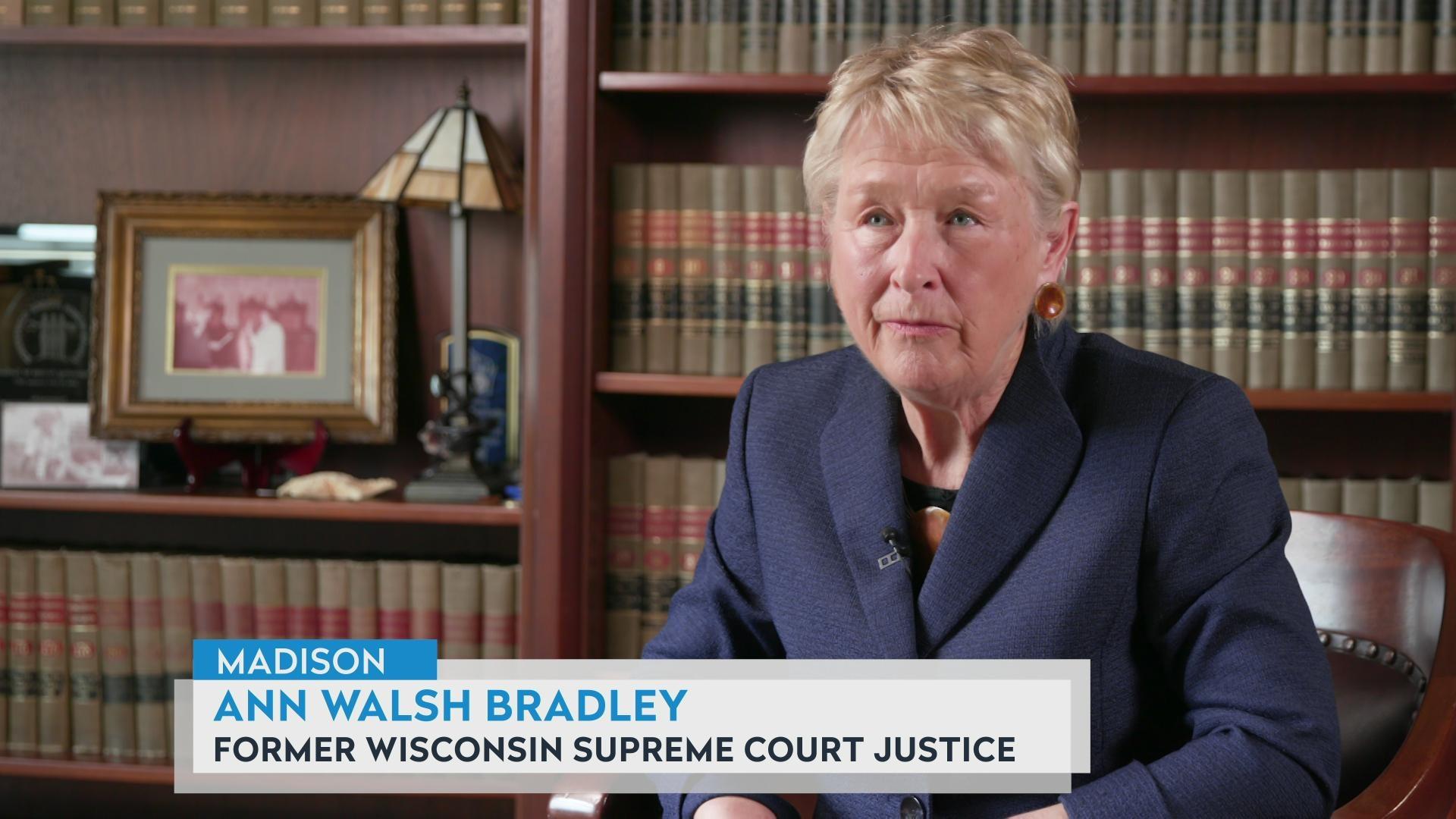

Dane County Circuit Court Judge Josann Reynolds is presiding over the case. Reynolds will have to decide what Wisconsin’s special-elections law actually means in this instance, and whether it’s appropriate for a court to force the governor to call special elections under these specific circumstances. Often a judge parsing such questions will have a body of relevant state- and federal-level court decisions to draw on for guidance. Not all of this precedent will speak directly to the specific circumstances of a case before the court, but it might lay out principles and tests that a judge can apply to the facts at hand. In Newton, though, it’s difficult to tell what if anything might provide guidance.

When judges have forced special elections

The plaintiffs’ lawyers cite several court decisions related to special elections in their filings, but all had to do with vacancies in the U.S. House of Representatives. Governors must fill House vacancies through elections, but that requirement is couched in Article I, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution. Questions of state law can still come into play in such cases, but they don’t center entirely around state law, much less shed light on how a state court should interpret Wisconsin’s statutes.

“The number of such suits is still relatively small, and it’s hard to generalize because the standards for calling special elections can vary from state to state and from office to office,” said Steven Huefner, an Ohio State University Moritz College of Law professor who has studied elections in Wisconsin and other Midwestern states.

Most states have laws or state constitutional provisions that direct governors to fill state legislative vacancies through special elections, but even those rules vary in their wording and details.

What about recent examples of conflicts over legislative vacancies? There are at least two cases of Republicans taking a Democratic governor to task over special elections, both of them in New York.

In 2010, New York Governor David Paterson, a Democrat, initially stalled on calling a special election for the state’s 29th Congressional District after Rep. Eric Massa, also a Democrat, resigned amid a sexual harassment scandal. Massa vacated his office in March of that year, and would have been up for re-election that November. In Fox et al v. Paterson, Republican voters sued the governor, who then relented and called a special election — for November. Unsatisfied with that date, the plaintiffs continued pursuing the lawsuit. A federal judge eventually ruled, in July 2010, that Paterson had a mandatory duty to call a special election, but required that it be held no later than the date of the November election. In this case, a stalling governor essentially got what he initially wanted.

The controversy that played out around Paterson’s handling of the 29th District was a note-perfect partisan reversal of what’s happening in Wisconsin. New York’s Democratic governor cited cost concerns, conservative commentators blasted him for effectively leaving the seat open for 10 months, Republican state legislators accused Paterson of playing dirty politics and pushed for an earlier special election, and journalists pointed out that delaying the district’s election until November could advantage Democrats, because Democratic U.S. Sen. Chuck Schumer was up for re-election that fall, which could spur strong turnout among left-leaning voters. (It didn’t actually work out that way — Tom Reed, a Republican, won the 29th District seat.)

In 2015, a federal judge once again had to force a governor of New York to call a special election to fill a U.S. House seat. Republican U.S. Rep. Michael Grimm resigned his seat in the state’s 11th District in January of that year after pleading guilty to federal tax fraud charges, ending a short but colorful Congressional career that also saw him threaten to throw a TV reporter off a balcony. Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, didn’t initially announce any decision about a special election. A group of voters and a Republican attorney, convinced Cuomo was stalling, sued him in early February, and a judge ordered the governor to call a special election. Cuomo relented, and the election was held in May 2015. Republican Dan Donovan won that election, and was re-elected to the seat in 2016.

More recently, Michigan Governor Rick Snyder, a Republican, is facing two controversies over vacant seats, one for a Congressional seat and the other for the state legislature.

U.S. Rep. John Conyers, a Democrat who represented the 13th District seat, resigned in December 2017. Snyder decided not to fill that seat until the Nov. 6, 2018 election. This decision prompted Michael Gilmore, a candidate for the seat, to file a federal lawsuit, which is ongoing. And in March 2018, after Michigan State Sen. Bert Johnson, a Democrat, stepped down after pleading guilty to corruption charges, Snyder decided to wait until November to fill that seat.

It’s telling that the initial complaint filed in Newton v. Walker doesn’t point to any instances of a judge ruling how state law requires a governor to act or not when filling a legislative vacancy. In the process of researching this story, WisContext failed to find any similar lawsuits seeking to force the state to hold special elections.

A shrug supreme

When it comes to broader Constitutional guidance in this case, there may not be a whole lot, said Ohio State law professor Steven Huefner.

One portion of the U.S. Constitution that’s relevant to special elections and legislative vacancies is Article IV, Section 4, which requires every state to have “a republican form of government.”

On the surface, that language pretty clearly creates a baseline expectation that states hold elections, and that a vacant legislative seat would be filled by an election. But it hasn’t been construed to spell out anything specific about special elections, which helps to explain why states have such widely varying approaches to filling vacancies in their legislatures. (The National Conference of State Legislatures has a guide to each state’s rules.)

The U.S. Supreme Court also punted on the whole “republican form of government” thing long ago.

Huefner points to the Court’s 1849 decision in Luther v. Borden, a case that stemmed from Rhode Island’s Dorr Rebellion. Insurgents challenged that state’s non-democratic form of government — which, among other things, granted voting rights only to white men who owned a certain amount of property — by claiming that it violated Article IV, Section 4 of the Constitution. The Court ruled that the question of defining a “republican form of government” was best settled by Congress or the president.

In essence, “the U.S. Supreme Court has essentially said there is nothing in this clause for the federal courts to enforce,” Huefner explained.

What about the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution?

“The Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantees of equal protection of the law and due process of law offer federal courts some ability to ensure that states honor at least those two central ideas of representative democracy,” Huefner said, “but with respect to how states actually conduct elections, those principles have had little to say.”

The 1965 Voting Rights Act also bolsters the guarantee of a republican form of government, but likely isn’t applicable to the scheduling of a special election, said Huefner.

Given the limited amount of constitutional guidance and legal precedent on state-level legislative vacancies, when deciding what its special-elections laws actually mean, Wisconsin’s court system may well be on its own.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us