The Doctor-Patient Relationship In The Opioid Crisis

In hindsight, it's plain to see that the boom in prescription opioids that started in the late 1990s coincided with an increase in opioid-related deaths in Wisconsin and across the U.S.

March 6, 2017

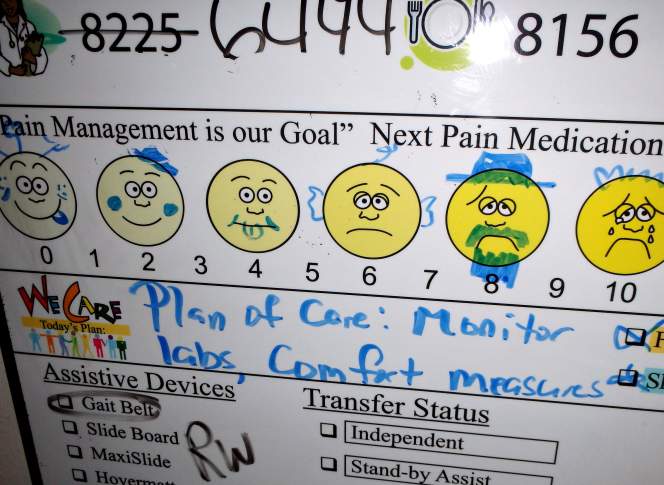

Pain scale on whiteboard at health clinic

In hindsight, it’s plain to see that the boom in prescription opioids that started in the late 1990s coincided with an increase in opioid-related deaths in Wisconsin and across the U.S. As that crisis continued to escalate in the 2000s and 2010s, spurring more people to abuse heroin and fentanyl in addition to prescription drugs, the medical profession has done a lot of debating and soul-searching about how it defines and measures pain, and how aggressively clinicians should use opioids to manage it.

This conversation can get reduced to a simplistic pendulum swinging between over-prescribing and under-prescribing, between neglecting patient suffering and pushing patients into addiction. A couple of Wisconsin-based physicians offered a more nuanced view in a Feb. 27, 2017 conversation on Wisconsin Public Radio’s The West Side. Dr. Alaa A. Abd-Elsayed of the University of Wisconsin Pain Management Clinic and Dr. Brandon Parkhurst of Marshfield Clinicdiscussed how the doctor-patient relationship is just as important as any decision about medication.

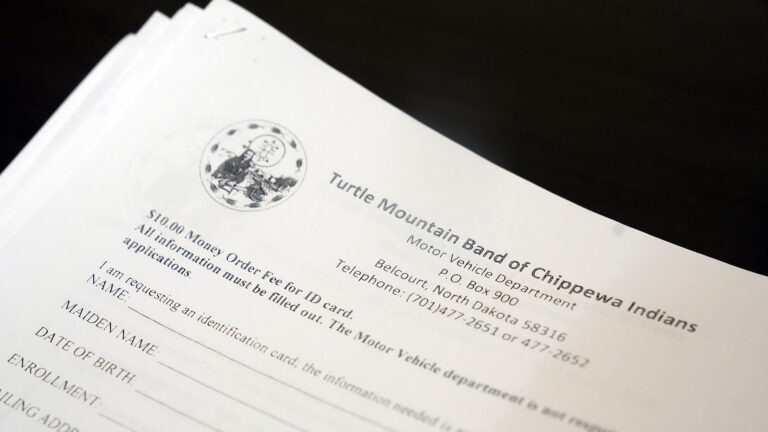

In this interview hosted by WPR’s Rich Kremer, Abd-Elsayed and Parkhurst joined Sgt. Andy Falk, an officer with the Eau Claire Police Department and supervisor of the multi-jurisdictional West Central Drug Task Force, a little over a month after Drug Enforcement Administration agents raided a Chippewa County clinic suspected of giving out opioid prescriptions improperly. The clinic, Cadott Medical Center, and its lead clinician, Dr. Clifford T. Bowe, specializes in treating chronic pain and providing medication for people recovering from opioid addictions. As the DEA continues to investigate the clinic, its patients remain in limbo.

Both prescription painkillers and opioid-based addiction treatments (methadone and buprenorphine) carry the risks of addiction and abuse. But it’s never the medication alone that takes a patient over the line from healthy medical use to dangerous abuse, Parkhurst pointed out.

“The safety really doesn’t come from the medication itself,” he said. “The safety comes from the actual act of monitoring and selecting the patient and through the mechanism of how you’re providing that.”

In other words, prescription drug abuse is a big-picture problem for each individual patient struggling with chronic pain. Effective pain treatment requires a comprehensive plan that may well involve medication, opioid or otherwise, but also needs to incorporate a patient-specific combination of other elements, from meeting with a pain psychologist to a course of physical therapy.

“Counting on medications only, I don’t think that is what should be done,” Abd-Elsayed said. “Some patients will need just pain psychology, some people will need only interventions and some patient will need a combination of all.”

There are also ways to manage pain medication use, such as trying non-opioid options before prescribing an opioid, and making sure patients who are on opioids experience periods without those drugs to prevent them from building up too much of a tolerance, Abd-Elsayed said. Carefully rotating a patient between opioid and non-opioid pain medications can head off addiction problems as well, he added.

Bowe told WPR’s Rich Kremer in January that he gave some of his patients high doses of opioids because they had built up tolerance, and said law enforcement investigators and other clinicians don’t fully understand the issue of opioid tolerance and how it impacts pain treatment. But in the Feb. 27 interview, Abd-Elsayed said the pain-treatment field has developed a better understanding of tolerance in recent years, and simply ramping up dosages in response to it is “an older concept that doesn’t apply to today’s practice.”

Doctors also feel pressure to make patients happy, which isn’t necessarily the same as serving the patients’ best interests. Surveys about patient satisfaction have become increasingly influential since the late 1990s, and the Affordable Care Act linked the concept to Medicare funding for hospitals. (In July 2016, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services announced it would remove pain management questions from Medicare’s patient satisfaction surveys.) Still, under the patient satisfaction paradigm, a patient who thinks their medication isn’t strong enough to treat their pain can have an impact on how their overall quality of care is measured. This doesn’t mean it would be healthier for a patient to just increase their dosage over the long run.

“A happy patient or a satisfied patient that has been given bad medical advice has been provided bad care,” Parkhurst said.

Parkhurst and Abd-Elsayed agreed that the answer is not simply to for clinicians to say no to a patient who asks for strong or potentially addictive painkillers. Instead, they should take the time to develop a well-rounded plan to reduce the patient’s pain. This approach requires clinicians to strike a balance between providing medically sound guidance and taking a patient’s thoughts and concerns seriously.

“We can’t just do what we want to do without involving the patient — the patient is actually the head of the team,” Abd-Elsayed said.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us