There's More To Silvopasture Than Just Cows And Trees

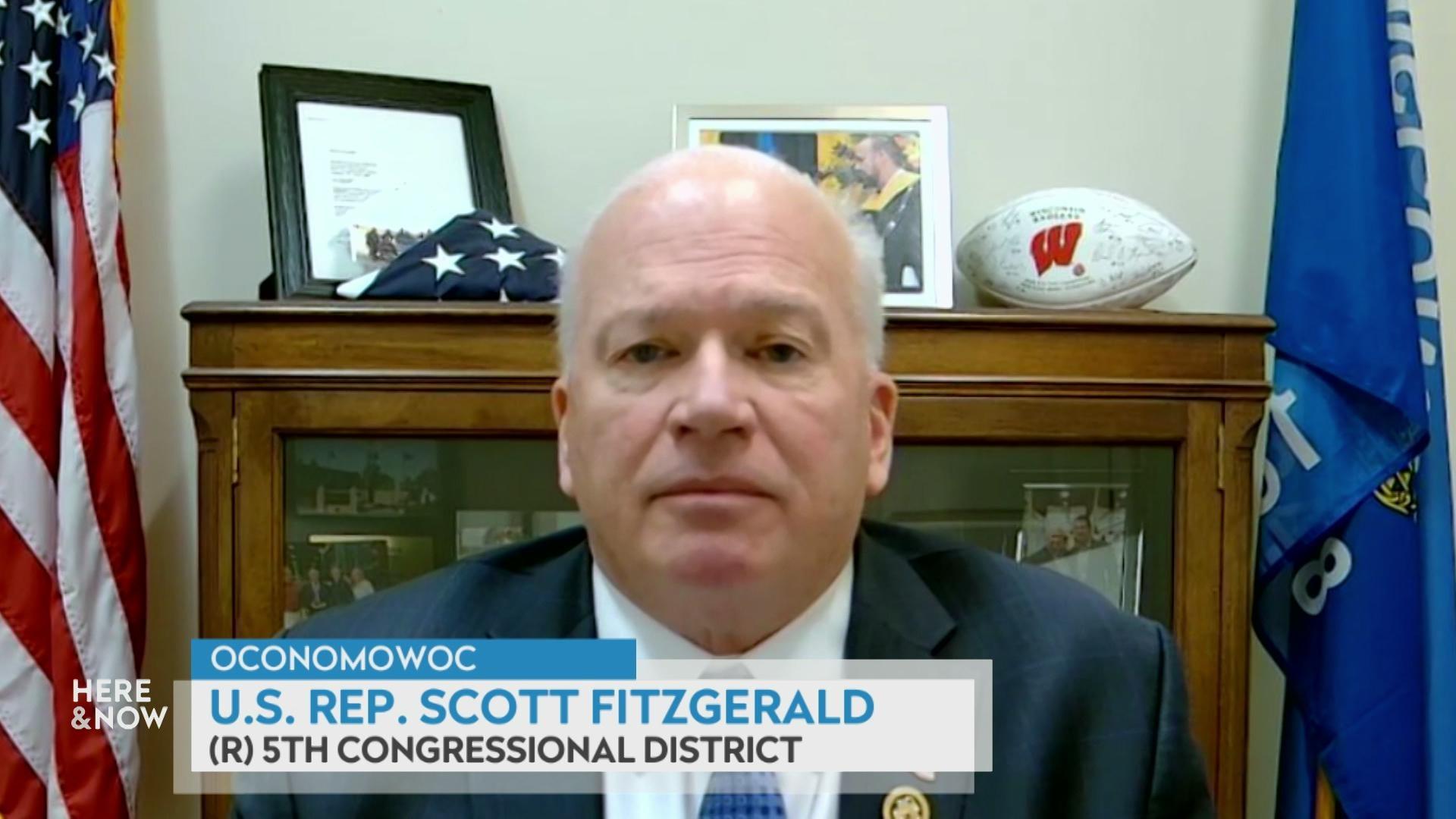

Cattle can often be seen grazing in meadows around Wisconsin, but they may also be finding their meals in wooded areas.

March 20, 2017

Cows on meadow in silvopasture

Cattle can often be seen grazing in meadows around Wisconsin, but they may also be finding their meals in wooded areas. Called silvopasture, the practice of grazing animals in the woods can bring long-term economic returns through forestry and annual income from livestock and forage. Trees shade the animals and help protect them from heat stress in summer. In winter, trees shelter animals from wind.

Silvopasture is defined as a type of agroforestry with the combination of timber, livestock and forage production on the same site. The challenge is managing all three production systems in a sustainable way that does not harm the animals, trees, soil and nearby water, said Diane Mayerfeld, a University of Wisconsin-Extension specialist in sustainable agriculture. She was one of the participants in a panel discussion at the Cooperative Extension State Conference on Nov. 11, 2015, recorded for Wisconsin Public Television’s University Place.

However, the practice of silvopasture is not widespread in Wisconsin. Researchers still need to learn about region-specific best practices that provide shade for livestock while enabling trees to thrive, noted the panel, which also included UW-Extension educators Vance Haugen, Randy Mell and Otto Wiegand, as well as UW-Madison Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology professor Mark Rickenbach.

But research by UW-Extension specialists and others that is underway should help identify the finer points of this grazing method, as well as help guide public policies that support and regulate it, along with nongovernmental ways to manage it.

Silvopasture is more than a farmer turning cattle or other livestock out into the woods, Mayerfeld said. For example, if cows are not managed well, they can damage trees and prevent saplings from growing. The farmer must provide the correct kind of food — forage — for the particular livestock as part of managing the woods in an integrated way. The farmer might plant appropriate forage in the woods or turn a pasture into a silvopasture by planting appropriate trees. In addition, grazing by cattle can be hard on fragile forest soil and contribute to the spread of invasive species.

Mayerfeld described the kinds of woods that should not be grazed and what landowners should look for when considering potential silvopasture sites. She noted that research on silvopasture in the southeastern and northwestern United States, while informative, does not necessarily shed light on how to get good results in Wisconsin.

Wisconsin’s farmers and resource professionals are interested in silvopasture and how they can use it to manage their land, Mayerfeld said, adding that demonstrations need to be conducted in the state. Silvopasture can also control invasive species and manage brush growth, but more information is needed about about tree species, which forages thrive with light shade and how to protect young trees. And people interested in this practice want to know about its costs and potential profits.

Key facts

- Silvopasture is one of five agroforestry systems, as defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: windbreaks, riparian (riverbank) buffers, alley cropping and forest farming. By combining production types, agroforestry can provide extra economic, environmental and social benefits. However, because they involve different agricultural systems at the same time, they can be more challenging to manage than more conventional farming or forestry approaches.

- Silvopasture can be used to graze beef cattle, dairy cows and heifers, sheep, goats, bison and poultry.

- Silvopasture can be developed from remnant savannas, which restore habitat that was prevalent in Wisconsin prior to European settlement. (For example, the UW Arboretum has several savanna restorations.) Some landowners see silvopasture lands as good habitat for wildlife that can be hunted.

- Landowners can establish silvopasture in an open area, in an open pasture or in an empty field, where trees would be planted and forage established at the same time. Another silvopasture option in Wisconsin is to thin woods, establish forage and introduce livestock into this landscape.

- Good silvopasture sites have an appropriate amount of light, trees big enough that livestock will not damage them and the right kind of soil. They also lack plants toxic to livestock. The landowner needs to know the site’s timber potential and how a stand of trees will be managed. People wanting to establish silvopasture in an open field need to know what kind of trees to plant and how they will be protected from the livestock.

- About 19 percent of the total acreage of farm wood lots in Wisconsin is grazed. In neighboring Iowa, about home 30 percent of this farm woodlots acreage is grazed, the highest level in the Upper Midwest. Other states around the U.S. have even higher grazing rates of wooded lands.

- About 35 percent of beef and dairy farmers in Crawford County use rotational grazing (frequently moving livestock among forage areas), one of the state’s highest percentages. About half of the county is forested, although it was mostly grass savanna prior to European settlement.

- Wisconsin property tax law gives landowners incentives to graze livestock in woods by taxing agricultural land at a lower rate to discourage its development for residential or commercial purposes. Therefore, if landowners graze livestock, they pay less in property taxes.

Key quotes

- Mayerfeld on silvopasture in Wisconsin: “Although [silvopasture is] a pretty accepted practice in the southeastern U.S. and also in the northwestern U.S., it has not been talked about a lot in the Upper Midwest. But Wisconsin farmers do have and value trees in their pasture, and they graze woodlands … We just haven’t talked about how they do it, and why they do it, and maybe how they can improve the management of it.”

- Mayerfeld on preliminary recommendations for silvopasture practices: “It’s really important to manage the grazing in a silvopasture system. We would recommend only using rotational grazing with silvopasture. At this point, we would recommend that any silvopasture paddock also includes some open pasture so that it wouldn’t be an entirely silvopasture pasture. … The water source [should] be away from the trees so that there’s a motivation for the livestock to move in and out and they don’t just park themselves under the trees. It’s very important to note that one tree or just a small group of trees is not a good idea because then you get too many livestock congregating in one space and that kills the grass; it can also be a vector, it can also encourage disease transmission between the animals.”

- Haugen on silvopasture in Crawford County: “We have a lot of opportunity to utilize some of the existing now-forested areas that then could come back into productive pasture without having some environmental difficulties.”

- Haugen on riparian grazing: “We also have a huge number of trout streams in Crawford County, and I’ve been working with Trout Unlimited, and we’ve been taking a look at putting together grazing near trout streams. … The idea is that we reduce the number of trees, we increase the amount of grass, and that it holds the soil better.”

- Mell on forestry practices: “I was trained was back in the late ’60s, early ’70s — and the training still continues for foresters, wildlife biologists and forest ecologists — that cattle in the woods are not a really [good] ecological remedy, and of course that’s our biggest background. … [But] working with restoration of woodlands that have been destructively grazed, I know the resilience that can happen once the cattle are either removed or they’re properly grazing in those areas.”

- Mell on tall-grass savanna: “We have a savanna, tall grass savanna, as a natural element, a natural forage and natural ecosystem in the southwestern part of Wisconsin. … That particular savanna is larger areas of open grass, tall grasslands, scattered areas of oak groves and of sometimes even just scattered individual trees, is what was recorded in past histories and … was a very, very strong type of ecological system.”

- Rickenbach on government forest policy: “[I approach silvopasture by] thinking about … the policies that we develop in the state and how they incentivize behaviors that we don’t have good answers for, and I think grazing in woodlands is a good example. We’re creating an incentive, a huge incentive, for landowners to graze woodlands and the response that we get from the forestry community is, ‘Well, don’t do it.'”

- Mell on working lands: “Just because foresters and ecologists and wildlife biologists have been trained against cattle in the woods doesn’t mean that they can’t adapt. Very few foresters have actually experimented with a planting process, and it would involve getting to know the local agricultural agent, different forage specialists, a number of grazing specialists, just knowing the livestock, the type of livestock that you’re going to be using in your woods … Not to say that it couldn’t be done, it just is going to take a little bit of a philosophical change in terms of the foresters. I don’t know if the wildlife biologists and/or forest ecologists would go along with that type of working land scenario. They’re really more interested in either migrating other wild animals and other wildlife that’s in that area, and or the forest ecologists of the other rare and endangered or other species in other communities that might be fragmented or segmented or damaged by grazing. But just identifying those particular areas on a private land and then identifying those areas that would be best suited for a silvocultural pasture treatment, I think, are definite possibilities in the future.”

- Rickenbach on forestry versus agriculture: “People have done very well in ways that most people would define as being a sustainable way of doing this, yet we don’t have guidance for others in how they might think about that. And I think this is kind of a disconnect between the forestry community, who has an interest in kind of maybe thinking more about traditional forestry and plantations and things like that, meeting the agricultural community and that’s already a difficult divide in this state.”

Editor’s note: This article is corrected to note that farm wood lots in Wisconsin are grazed at rates of about 19 percent.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us