A Midcentury Revolution In Farming Would Change Wisconsin Forever

Technological changes — electricity and mechanization — in the mid-20th century would revolutionize the practice and business of agriculture in Wisconsin, and set into motion economic and demographic changes that continue well into the 21st century.

August 28, 2019

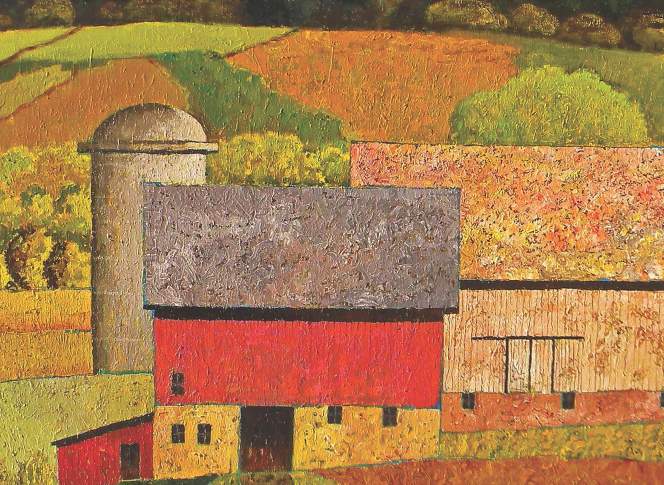

'Wisconsin Agriculture: A History' book cover crop

Farming and its ways of life are at the foundation of human civilization, its practitioners and products establishing the cultures and economies of local communities, regions and peoples across history. Wisconsin is defined by its long-cherished status as an agricultural state, its self-identity and global reputation shaped over many decades by its best known foods and the plants and animals responsible for providing them. But agriculture is a constantly changing enterprise, including in the dairy state. Initially a major grower of wheat around its founding, the state would become a center of milk and cheese production by the 20th century. Agriculture is also diverse in nature, particularly in Wisconsin. Along with dairy and major commodity crops like corn and soybeans, the state’s farmers cultivate a variety of vegetables, fruits, and livestock for meat, fiber and fur, along with a host of specialty products. Jerry Apps, a former University of Wisconsin-Extension agent and professor, rural historian and contributor to Wisconsin Public Television, recounts the development of farming around the state in the 2015 book Wisconsin Agriculture: A History, published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press. An excerpt from the book examines how technological changes — electricity and mechanization — in the mid-20th century would revolutionize the practice and business of agriculture, and set into motion economic and demographic changes that continue well into the 21st century. As farms grew in size and fewer people made their livings and grew up on them, the communities of rural Wisconsin would be transformed — a shift that would reverberate throughout the state.

The first agricultural revolution, which began in the 1830s, saw the heavy draft horse breeds replace the sturdy oxen that had done the heavy work on the farm since colonial days. And then, for many Wisconsin farmers, farming methods remained relatively unchanged for a long time to come — nearly a century, for some.

The next big changes in agriculture began during World War II and became more evident in the years immediately following. This revolution was marked by electricity replacing lamps and lanterns and tractors putting horses out to pasture. Agriculture was evolving in other ways as well, but electricity and mechanization were the core of sweeping changes.

As historian William F. Thompson wrote, “There was much that was familiar throughout Wisconsin in that last full year of peace before the war. The climate and seasonal rotation remained much as they had been at the time of settlement, varying only slightly from year to year … Few people foresaw sprawl or pollution, much less a rate of change in their physical and social surroundings that was governed only by its own momentum.”

Electricity comes to the country

Arguably, electricity influenced farm operations and farm family life more than any other technological innovation — before or after.

With electricity in his barn, a farmer no longer needed a pocket of matches to strike the wicks of the lamps and lanterns that had lighted his way for years. With the pull of a lever, a pump motor came alive and began pumping water. Turn another switch, and the milking machine began pulsing, allowing the farmer to add several more cows to his dairy herd. And with yet another switch, a barn cleaner automatically moved the animal waste to the manure spreader standing outside the barn, without the farming having to touch a shovel or fork.

On my home farm, we no longer had to hope for a bright moon to light our way to the barn for morning and late-afternoon chores; now a yard light showed the way. And I stopped carrying a lantern up to the haymow, for with the flip of a switch, the haymow was as bright as day.

According to the report “Wisconsin Agriculture in Mid-Century” prepared in 1953 by the Wisconsin State Department of Agriculture, electricity was “one of the best and cheapest workers on Wisconsin farms… It is used in the performance of numerous farm tasks as well as providing light, power and fuel for the farm home. The water that flows in the barn is often supplied by an electric pump. Electricity is used for the milking machine, milk cooler, feed grinder, fans, radios, washing machines and many other items.”

By 1950, 93% of the farms in Wisconsin had electricity, paying an average monthly bill of $9.74.

Mechanization arrives on the farm

After essentially replacing oxen in the mid-19th century, horses continued to handle the heavy work on the farm through the Depression years. Many farmers didn’t purchase their first tractor until after World War II. During the Depression, when gas tractors became available, many farmers simply couldn’t afford them. (A handful of farmers owned steam tractors, mostly used for powering threshing machines.) Most farmers were accustomed to farming with horses and enjoyed working with the animals.

In the 1950s, prosperity led more farmers to add tractors to their farm equipment. And with tractors came a new generation of tractor-powered farm machinery. Dairy farmers needed a barn full of hay to feed their hungry cows throughout the long winters, and hay making with horses was slow, tedious, dusty, and dirty work. Thankfully, tractor-pulled hay balers allowed the farmer to forgo bunching newly raked hay by hand, pitching it onto a horse-drawn wagon, and then forking it into the haymow.

With tractors and newly developed forage harvesters, corn binders were eliminated, and tractor-pulled grain combines eliminated the need for grain binders, for shocking grain by hand, and for the threshing crews that moved from farm to farm.

In the wake of these technical innovations, communal work gatherings such as silo-filling bees and threshing bees disappeared. These work bees not only helped neighbors with the harvest, but were social events and a way to tie rural communities together.

Changes in rural communities

This second revolution affected farming practices and had profound structural effects on rural communities. The most obvious was the decline in the number of farms. With tractors, electricity, and new disease-resistant and higher-yielding crop varieties, Wisconsin farmers could grow more crops and milk more cows with less human power than ever before.

As a result, farmers, and especially farmers’ children, had fewer opportunities in farming. Starting in the late 1940s, with more young people having completed a high school education, many of them left the farms for work in the cities. Some of the more fortunate young people left to attend college.

The number of Wisconsin farms had peaked in 1935 at around 200,000; by 1950 that number was down to 168,561 and falling. At the same time, the average size of a Wisconsin farm increased from 117 acres in 1935 to 138 in 1950. In 1910, 35.7% of Wisconsin’s citizens lived on farms; by 1950, that percentage had fallen to 21.3.

As the number of farms shrank, farms themselves became larger, and the farm population declined, rural communities changed dramatically.

One-room country schools, a prominent feature in all Wisconsin communities, were mostly closed by the mid-1950s, as school buses transported the remaining young people on farms to the consolidated schools in the nearby villages and cities. Many country churches closed as well. Crossroads cheese factories ceased operations as trucks and improved roads made travel from farm to market easier. And with better roads and better cars, people traveled farther to large retail centers for their purchases, causing smaller villages to lose business.

Wisconsin’s farm economy at midcentury

Income from Wisconsin’s dairy industry grew steadily during World War II, reaching $300 million in 1943 and more than $500 million in 1946, increases due mainly to the greater demand for dairy products during the war. In 1948, Wisconsin’s dairy income reached $590 million; it dipped to $580 million in 1952.

One reason for the increased income from milk was how it was priced. Milk pricing in the United States was affected by milk marketing orders, which were instituted in 1949. These milk marketing orders provided a floor for the amount of money dairymen received for their product. When there was more milk than the market required, the government stepped in and bought dairy products, thus keeping milk prices from falling as far as they otherwise might.

The sale of cattle and calves was the second major source of Wisconsin farm income at midcentury, reaching $200 million in 1951. The sale of hogs ranked third ($129 million) and poultry fourth ($111 million).

Life on a Wisconsin farm, 1950

By the mid-20th century, many Wisconsin farm homes were beginning to see the transforming effects of modern conveniences including indoor plumbing, central heating, and electricity.

A writer for the Wisconsin Crop and Livestock Reporting Service described the farm home at midcentury as being

surrounded with evidence of an advancing agriculture. The springhouse is replaced by the refrigerator, and modern methods of food distribution and the deepfreeze have eliminated much of the necessity for home canning. Telephones, electricity, radio, television and automobiles have all contributed to improved rural life in Wisconsin. . . . By 1950, 87 percent of Wisconsin farmers had electric washing machines. . . . Forty percent of the farm home wood heaters had been replaced with central heating. About fifty percent had water piped into the home.

Not all farm families, however, wanted — or could afford — to upgrade their operations, and many Wisconsin farms stepped into the second half of the 1900s with one foot firmly planted in the past.

David Shekoski recalled that in the 1950s, his grandparents Gustav and Elizabeth Fritz heated their farmhouse near New London with wood-burning stoves, including the ancient, massive one in the kitchen.

“It was amazing what my grandmother could do with that stove,” he remembered. “If the cooking temperature was a little too hot or too cool, she knew exactly where to slide the kettle to achieve the correct cooking temperature. There were no temperature settings to adjust except the stove vents on the firebox and the damper in the stove pipe.”

In summer, Elizabeth prepared meals on a kerosene stove in the summer kitchen to avoid heating the house. And indoor plumbing remained “something only to be dreamed about.”

Yet apart from that,

[T]he house was equipped with all of the conveniences of modern times. Running water was fed directly into the kitchen by a hand pump mounted next to the sink. (Apparently the well was drilled and the house was built around it. There was another pump in the back yard between the house and the barn.) Electricity was brought to the house through wires that extended from a pole next to the road and entered the house through the kitchen wall. The extent of electrical service was one outlet in the kitchen (which operated the refrigerator and the radio, which sat on top of the refrigerator), a wire that ran to the ceiling for the kitchen light, and another wire that ran along the wall to the single outlet in the living room.

When farm families did decide to make improvements, those upgrades often took place in the barn before the house.

At my home farm, we installed running water in the barn twenty years before we had indoor plumbing in the house. As my father often said when I asked why conditions in the barn seemed better than in the house, “There is no income coming from the house.”

The years from the end of World War II into the early 1960s were a time of tremendous change in Wisconsin agriculture. Not only did total farm numbers continue falling from their peak in 1935, but the number of dairy farms declined as well. In 1965, Wisconsin had 86,000 dairy farms (124,000 total farms). By 1970, the number of dairy farms would fall to 64,000 (110,000 total farms).

Many young people left the land to find employment in cities. Those remaining on the farm now felt the need to purchase more land and invest in the mechanization required to farm more acres. Dairy farmers purchased more cows and built larger barns and silos, and their debt levels rose. Some left dairy farming to concentrate on raising cash crops — mainly corn and later soybeans — for sale off the farm. Others left dairy farming to grow vegetables and other specialty crops.

This item was excerpted from Wisconsin Agriculture: A History, published by Wisconsin Historical Society Press.

Jerry Apps was born and raised on a central Wisconsin farm. He is a former county agent for the University of Wisconsin-Extension and professor emeritus for the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at UW-Madison. He is the author of more than forty fiction, nonfiction and children’s books, with topics ranging from barns and cheese factories to farming with horses and the Ringling Brothers circus, and his experiences are detailed in multiple Wisconsin Public Television documentaries, including Jerry Apps: A Farm Story, A Farm Winter with Jerry Apps, The Land with Jerry Apps, Jerry Apps: Never Curse the Rain and Jerry Apps: One-Room School.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us