'I feel like I'm dreaming': Afghan refugees embark upon new lives in Wisconsin

Whether they fled to the U.S. after the fall of Kabul or in previous years, Afghans hoping to build new lives in an unfamiliar place rely on the help of lawyers and resettlement agencies even as they strive to overcome the trauma of departing their original homes.

By Marisa Wojcik | Here & Now

January 31, 2022 • West Central Region

This story is part of a PBS Wisconsin/WPR WisContext collaboration, utilizing reporting, research and community-based expertise to provide information and insight about issues that affect Wisconsin.

“It’s just like completely shocking. It’s just like, oh my God, I was never expecting this. And it just happened all of the sudden,” said an Afghan man who worked with the Marines.

“When I saw the news, I’m so upset. I am so sad,” said another Afghan man who likewise worked with American troops.

“People saw chaos and it was awful. The way that the United States had to leave,” said a Madison immigration attorney.

“Everybody just try to escape because they want to survive,” said a journalist from Kabul.

“Basically the Taliban had overrun the city and the airport. To me it was like Kabul fell,” said a leader for a Wisconsin-based charity.

Images of crowds of people outside the Kabul airport, waiting on tarmacs, and being packed into military planes saturated screens around the world as the U.S frantically evacuated people out of Afghanistan in August 2021 and the Taliban seized power.

In August 2021, Afghans seeking to flee from the impending takeover by the Taliban crowded the grounds of the Kabul airport, guarded by U.S. military personnel. (Credit: Courtesy of PBS NewsHour)

The emergency evacuation airlifted more than 120,000 people. Thousands were brought to Fort McCoy near Tomah. Less than half a year later, hundreds of families are settling in, calling Wisconsin their new permanent home. But there is still an uphill climb to find housing, navigate the immigration system, and sort through the trauma of leaving their home to the hands of the Taliban.

“Everyone who doesn’t think like them is an enemy to Taliban. And you can get killed for the basic reason as living in Kabul,” said Sher Khan, a journalist.

Khan was evacuated from Kabul with his wife and children in 2021 and they reached Fort McCoy in September. Now, with the Taliban in power, many have lost hope for those they left behind in Afghanistan.

Journalist Sher Khan, sitting with his son, fled from Afghanistan with his family in 2021, arriving at Fort McCoy in September. He expresses incredulity and appreciation for the magnitude of the effort to help Afghan refugees. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

“I was hoping that I get graduated and then go back home so I could surprise my family. But that never happened,” said “Johnny,” who came to the U.S. in 2014 on a Special Immigrant Visa, or SIV, for work he did to help the U.S. military.

“I was receiving threats, like text messages and then phone calls while I was working with the U.S. Marines,” Johnny said. “I decided not to stick around anymore and just move to the U.S.”

Johnny’s identity is being protected in this report because he fears his family still in Afghanistan will be targeted. His family tried, but were unable to make it to the Kabul airport.

“The day that explosion happened, they left 30 minutes before, you know, like 30 minutes before,” Johnny noted, referencing a suicide bomber attack at the Kabul airport on Aug. 26. “Can imagine they were there? You know, like you could have lost the entire family.”

For many families, it’s a similar story.

“I am concerned about my two brothers. They worked with the military, said Khalid, who came to Wisconsin in 2017, after receiving threats for his work with the U.S. Two of his brothers are being targeted by the Taliban five years later. They, too, were unsuccessful getting into the Kabul airport.

Khalid worked with the U.S. military in Afghanistan but fled the nation in 2017 after being threatened. He still has family members in Kabul who were unable to leave during the August 2021 airlift. He has been working as a translator for Afghans who made it to the U.S. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

“They punish them: Go away from airport,” said Khalid. “They hit him by the gun and they broke his arm.”

Khalid’s brothers have fled central Kabul for safety, only visiting their families under the cover of darkness.

“Neighbors are being threatened by the Taliban because they lived next door to someone that is known to have worked for the U.S. or a U.S. company. Just proximity could put you in danger,” said Mary Flynn, a refugee resettlement program manager for Lutheran Social Services of Wisconsin and Upper Michigan, based in Milwaukee.

Lutheran Social Services of Wisconsin and Upper Michigan is one of several local resettlement agencies that is helping Afghan refugees establish new roots in communities around the state. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

“The new generation, they hoped for the future. But now, they don’t have hope for the future,” said Khalid.

“There is no hope of future for the people. For example, even if [the] Taliban didn’t kill me, my children would not get the chance to get education, and I don’t want to see that. I would have done everything I could to provide my children to get their education, because I don’t want my children to be extremists. I don’t want my children to be fundamentalist. I want my children to do something to make a positive difference in other people’s life. That’s what they are supposed to do,” said Khan.

“In terms of money, in terms of jobs, in terms of the economy, in terms of how people are escaping the country and no education — it’s just like so many different things,” Johnny said.

With Kabul’s airport closed to people seeking to leave Afghanistan, the only way out for Johnny’s family is to flee to a neighboring country, a journey his young sisters cannot weather.

“Those little girls won’t be able to walk for 20, 25 days in a row — that’s just impossible to just get to another country. There’s no flights, there’s no transportation and they don’t have the documentation. I am really hoping that someone will see and hear my voice and do something about it. You know, we were promised that we will be saved and our family will be saved,” Johnny said.

“Johnny” worked with the Marine Corps in Afghanistan and came to the U.S. in 2014 on a Special Immigrant Visa after receiving threats. He fears for family members who remain in Afghanistan and were unable to flee Kabul. As more Afghans have arrived in U.S., he is trying to help their experience by working as a translator. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

“Honestly, when we’re at Fort McCoy talking with people about their own asylum case, their own SIV or a way to stay in the U.S., they almost always start out with, ‘The most important thing to me is what can I do for my family or my friends or my colleagues who are still in Afghanistan,’ and they’re deathly afraid, for good reason, [of] what could happen to them,” said Grant Sovern, an immigration attorney in Madison.

“What we realized about two months into everybody being here is they’re going to have to apply for asylum like everybody else does who is afraid to go back home,” said Sovern, who is the board president of the Community Immigration Law Center.

While many people qualified for special immigrant visas, at least half were designated with something called parole status. Sovern helped with legal orientation efforts at Fort McCoy, running clinics to help people start to think about the asylum application process.

“We all assume you can get asylum because your country is falling apart, and that is not what asylum is about. You have to show that you will be — you specifically — will be singled out because of one of these grounds,” he said, referencing five factors motivating persecution that determine asylum eligibility in the U.S. “So it’s a long process.”

Immigration attorney Grant Sovern does pro bono work for refugees, including helping teach about how the asylum process works. “They’re going to have to apply for asylum like everybody else does who is afraid to go back home,” Sovern explains. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

For Sovern, who has been doing pro-bono immigration work for years, there’s been a lack of legal resources long before this moment.

“This is certainly the most acute and the largest number of problems for the resources that we already don’t have, and a timeline that has to be achieved,” he said. “Otherwise we could be sending people back to Afghanistan.”

Sovern explained that anyone with parole status has one year upon entering the U.S. to file the paperwork applying for asylum, and two years to be approved. But they need a permanent address first.

“Right now, we are just all scrambling with the surge. We can’t even do anything else,” said Flynn. Lutheran Social Services is handling refugee resettlement cases in the Milwaukee area. Agencies help with a long list of items, but most important and desperately needed is affordable housing.

“The increasing prices are making it more difficult because we always want to have them be self-sufficient — the dignity and respect of learning life in America and doing well. We want them to do well,” said Flynn.

Mary Flynn is a program manager for refugee resettlement with Lutheran Social Services of Wisconsin and Upper Michigan. She points to finding affordable housing as a particularly difficult hurdle for refugees. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Johnny said Wisconsin is a good place for refugees to resettle.

I love cheese and I’m kind of turning to something more like a Wisconsin person. I really don’t like the cold, but beside that, I love Wisconsin,” he said.

Johnny and Khalid are helping out as translators for newly arrived families.

“I’m not done with serving and I really want to be somewhere — so I can be proud of my family and both of my countries,” said Johnny.

“I help as a volunteer because our Afghan culture. When you are an Afghan somewhere, they will need the help — you have to help,” said Khalid.

Afghan refugees who arrived at Fort McCoy and are moving on to resettle in Wisconsin and elsewhere around the U.S. are on a long road to making new homes for themselves. (Credit: Courtesy of Fort McCoy)

As local organizations around Wisconsin work to settle more and more people, they’re hoping communities will step up and help with resources.

“I think it’s a real opportunity for all of us to practice the welcome that really is Wisconsin,” Sovern said. “But the welcome also includes, providing a safe community where they can live. Right now, it means finding other ways to help. Their local refugee resettlement agencies are needing places for them to stay, are needing clothing and kitchen supplies and school supplies for kids when they’ll go to school. But they also need legal support. I think I would count them as lucky if they ended up in Wisconsin, because I think there are a lot of people who believe in that kind of thing, and I think people will step up and help.”

Flynn expressed a similar sentiment.

“I think that we always have to remember that this could be us. When you think of it that way, you see the importance of being kind and compassionate and making them feel welcome like you’d like to be,” she said.

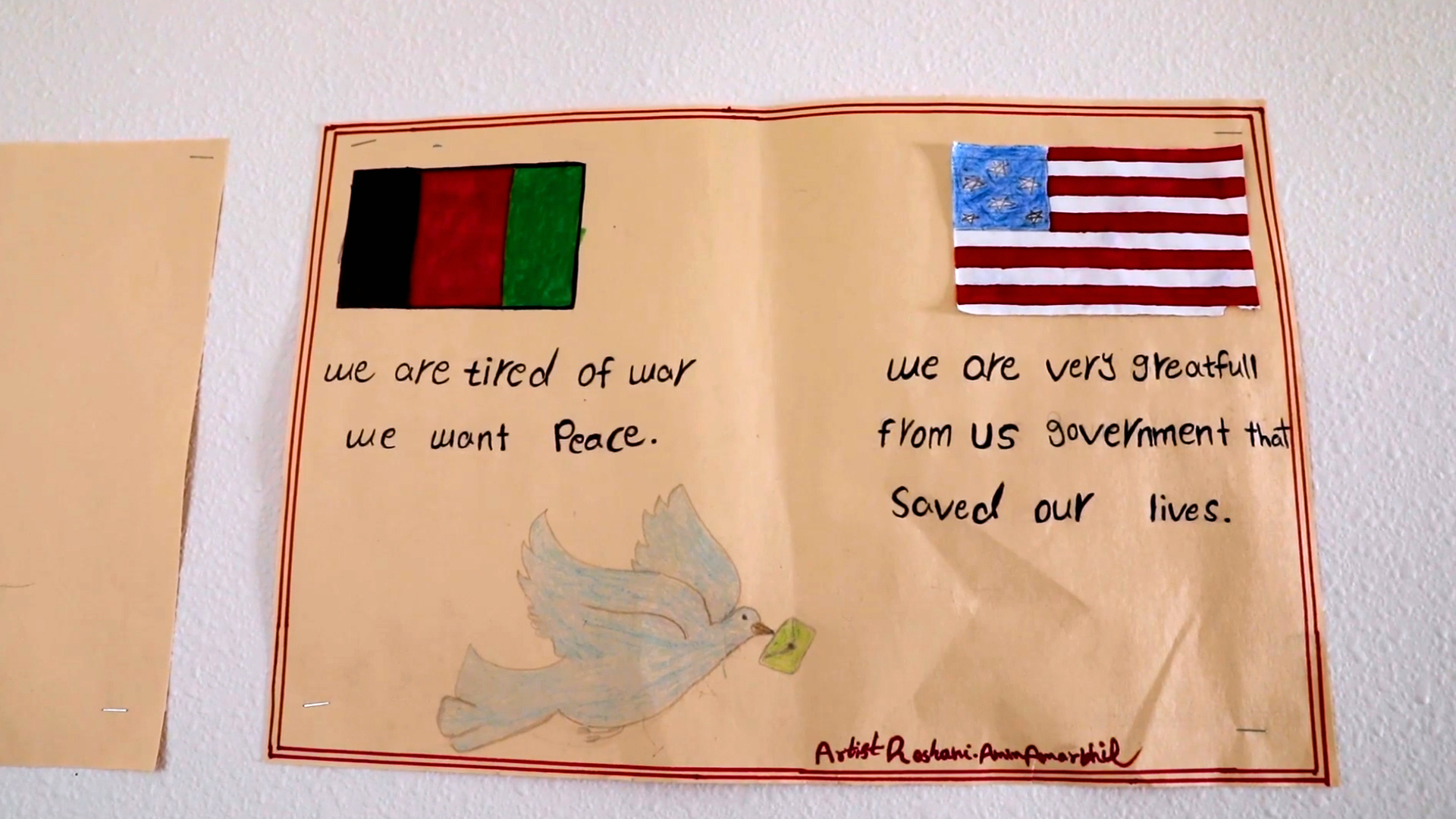

A hand-drawn poster at Fort McCoy expresses common sentiments among Afghan refugees seeking to restart in U.S.: weariness over decades of strife in their former home and appreciation for a new start. (Credit: Courtesy of Fort McCoy)

“Bringing this amount of people from one side of the world to the other side of the world and giving them all the things they need, that is just beyond my imagination,” said Khan. ” I mean, sometimes I feel like I’m dreaming. Whatever we receive here, we are thankful for.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us