Wisconsin Pride – Part Two: Struggles and Victories

Announcer: This program is brought to you by the combined resources of the Wisconsin Historical Society and PBS Wisconsin.

§ §

Dick Wagner: We define ourselves as a society by the stories we tell. If we don’t tell the stories of LGBT history, then we’re basically erasing them as if they didn’t exist.

Narrator: The history of Wisconsin has long been told from a particular point of view, one that has often concealed LGBTQ+ people.

Scott Seyforth: As I came out as a gay man, I looked for those stories. I have to tell you; those were hard to find.

Ashley Brown: There can be a tremendous silence about individuals and communities. That silence has not been accidental.

Narrator: Long hidden, these are stories of extraordinary Wisconsinites.

Josie Osborne: They’re people who blazed a trail, people who did great things.

Michail Takach: The resilience of these people in a world that feared them, outlawed them.

Narrator: But no longer would they be hidden. A movement was born. A stance on freedom was made.

Víctor Macías-González: We organized, we learned, we changed things.

Dick Wagner: These Wisconsinites were liberating themselves. Somehow, despite the oppression and homophobia, they had a place.

Narrator: Their stories reveal a larger tapestry of our collective past.

Will Fellows: It’s not just LGBTQ history or queer history. It’s also just Wisconsin history.

Narrator: Wisconsin Pride.

Announcer: Funding for Wisconsin Pride is provided by Park Bank, S.C. Johnson, Greater Milwaukee Foundation, Evjue Foundation, the charitable arm of the Capital Times, CUNA Mutual Group, New Harvest Foundation, West Foundation, Paula Bonner and Ann Schaffer, La Crosse Community Foundation, MG&E Foundation, Rogers Behavioral Health, with additional support from and with support from Focus Fund for Wisconsin Programs, and Friends of PBS Wisconsin.

§ §

Dick Wagner: Wisconsin has been a trailblazer in ways that very few people understand. And that’s an important story to tell.

[crowd shouting]

Narrator: The 1960s sparked a sea of social change across America. With it, the gay rights movement.

Judy Greenspan: We often hear about what happened in San Francisco, what happened in New York City. But we don’t hear about what happened in Wisconsin.

Narrator: In Wisconsin, LGBTQ+ people were ready to make a statement about freedom, to live openly, and to change American history. But it all began with a distinctly Wisconsin institution– the neighborhood bar.

§ §

Dick Wagner: Taverns are ubiquitous in Wisconsin.

Michail Takach: Wisconsin really was a breeding ground for bars of all different kinds. There were bars that were Serbian. There were bars that were African American. There were bars that were Polish. So, the idea of there being bars dedicated to gay people shouldn’t be surprising to anyone.

Narrator: In the post-World War II era, gay bars began to find a footing among a booming population. Though intense secrecy surrounded their existence, they started to play a pivotal role in LGBTQ+ lives.

Michail Takach: They went there to find community. They went there to find love. They went there to find hope.

Víctor Macías-González: You make friends, develop networks, and gradually begin to develop knowledge of what the gay world is.

Dick Wagner: About the only place you could actually be gay since you had to be straight at work and in your family was at a gay bar.

Narrator: The bars themselves kept a low profile, hoping to avoid attention from the police.

Víctor Macías-González: It’s almost like a holdover from the speakeasy culture. It won’t be marked. Right? The entrance is in the back. If they don’t recognize you, they won’t let you in sort of a thing.

Dick Wagner: It was not uncommon for police raids to occur in gay bars.

[police sirens]

The enforcement of norms and homophobia was a routine activity in those days.

Narrator: The police could carry out genital searches. Same-sex dancing could lead to an arrest. And bar owners could lose their license if caught serving homosexuals.

Michail Takach: The consequences were really extreme, and people still dared to live their best life. They still went out looking for each other, eager to find each other in a world that was actively trying to shut them down.

Narrator: In the summer of 1969, in New York City, six days of protests and clashes with law enforcement erupted following a police raid of The Stonewall Inn, a local gay club. The Stonewall Uprising would become famous as the catalyst for the gay rights movement in America. But anger had been brewing across the country well before Stonewall became a flash point.

[rumbling skies]

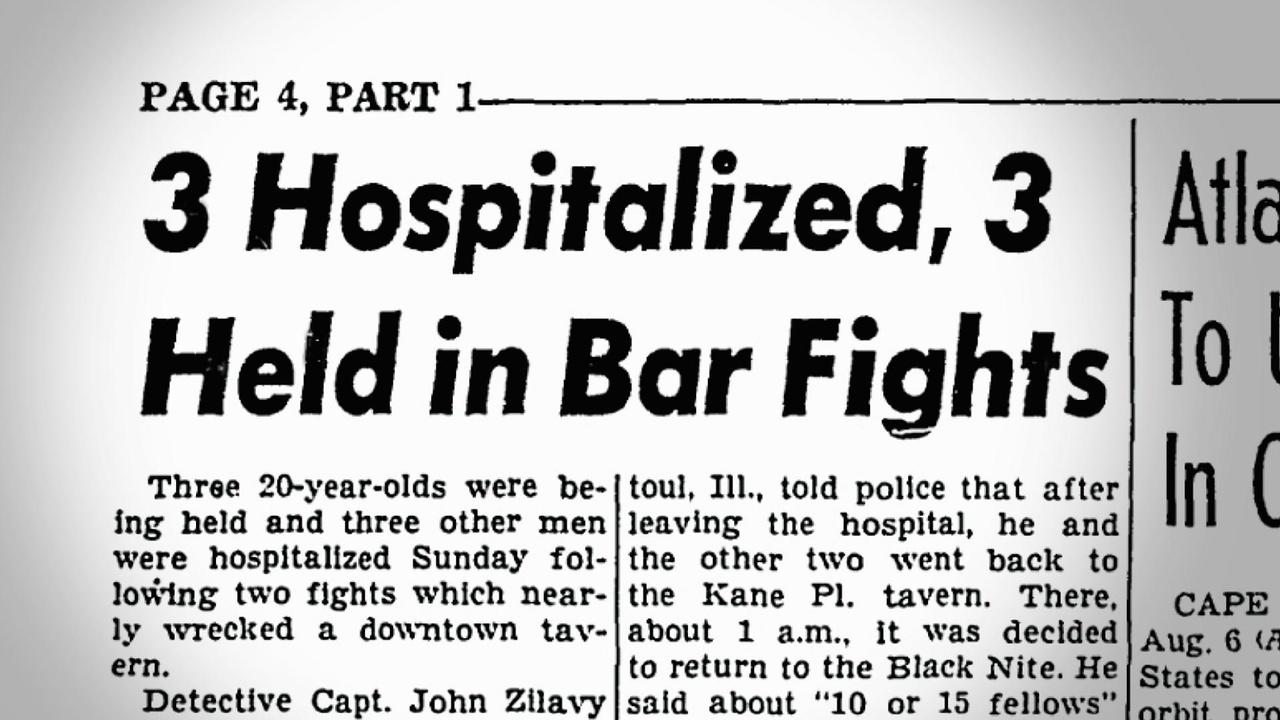

Michail Takach: Eight years before Stonewall, the Black Nite Bar was the scene of the first LGBTQ uprising in Wisconsin history.

[thunder claps]

Narrator: A rainy August 5, 1961. After a night out on the town, three sailors found themselves outside the Milwaukee gay bar, The Black Nite. The servicemen had been sent there on a dare. When asked to show their ID at the door, they panicked, dragged the bouncer outside, and attacked him. A nearby bar patron refused to stand by and do nothing.

Michail Takach: The heroine of The Black Nite was Josie Carter, an African American gender non-conforming queen of color.

Josie Carter: I’m Josie Carter. And, oh gosh, look out!

[shrieks warmly]

Michail Takach: Josie ran out there with a beer bottle in each hand and knocked one of the sailors unconscious and hit the other one over the head.

[glass shattering, shouting]

They dragged their friends out of there and said they’d be coming back to teach gay people a lesson.

Narrator: Bullied as a child, a survivor of sexual violence, Josie Carter refused to be harassed any longer.

Josie Carter: I have to be me. If I can’t be me, what the hell?

Michail Takach: Josie really was everyone’s best friend.

Narrator: For Josie Carter and her friends, The Black Nite Bar was a second home, a place worth fighting for.

Josie Carter: Just let me live my life, and you live yours. And we’ll get along beautifully.

Narrator: She warned the others in the bar about the attack, rallying them to stand their ground.

Michail Takach: People got really mad because they were like, “We have this one space. “We have this one space in Milwaukee “we can go and be ourselves “and dress however we want and express however we want. And now, they’re coming in here and harassing us.” And Josie’s response was, “We don’t run from a fight.”

Josie Carter: I’m not a runner. I mean, the high heels… I’m sorry. I do not run.

Narrator: The sailors returned with about a dozen others in reinforcements, but were in for a surprise.

Michail Takach: The sailors were met by 74 bar patrons who were mad as hell and not taking it anymore.

[angry shouting]

Narrator: The two sides clashed.

Michail Takach: The brawl literally destroyed the bar. All the windows were broken. All the glass in the bar was broken. Everything was just destroyed.

[police siren]

Narrator: The police broke up the fight and arrested the three sailors. The violence that night drove the headlines. But a larger message was sent.

Michail Takach: Other gay people saw news clippings about “The Black Nite Brawl” and said, “Oh, my gosh, there are people like me. “And they’re not putting up with it. And they are fighting back.” This was a big deal in 1961.

Narrator: Beyond a place of refuge, the gay bar became a symbol of liberation, galvanizing a community.

Víctor Macías-González: There wouldn’t be a gay movement without gay bars.

Michail Takach: The Black Nite was the first in a series of dominoes that fell that really advanced Wisconsin on the national landscape in terms of gay rights, gay protections, and gay awareness.

Narrator: But the fight for equality was only just beginning. And an age of activism would soon follow.

[angry crowd]

Dick Wagner: The ’60s had seen a whole range of activism here in Wisconsin. You had the anti-war movement, which was very strong on the Madison campus. In Milwaukee, you had a push for Black Civil Rights. There was a sense that there was this activism, which was a way to change things.

Protester: Sisterhood is powerful!

Narrator: A generation began to rise up during a time of political and social strife. Advancing a variety of movements, including gay rights.

Dick Wagner: There was this impetus that it was time to do something. Stonewall sent that signal, and people responded to it.

Narrator: In 1969, TIME magazine’s cover story, “The Homosexual in America,” put gay life into the national conversation. This inspired an anonymous writer at the University of Wisconsin-Madison to publish an open letter in the campus paper calling for homosexuals to band together.

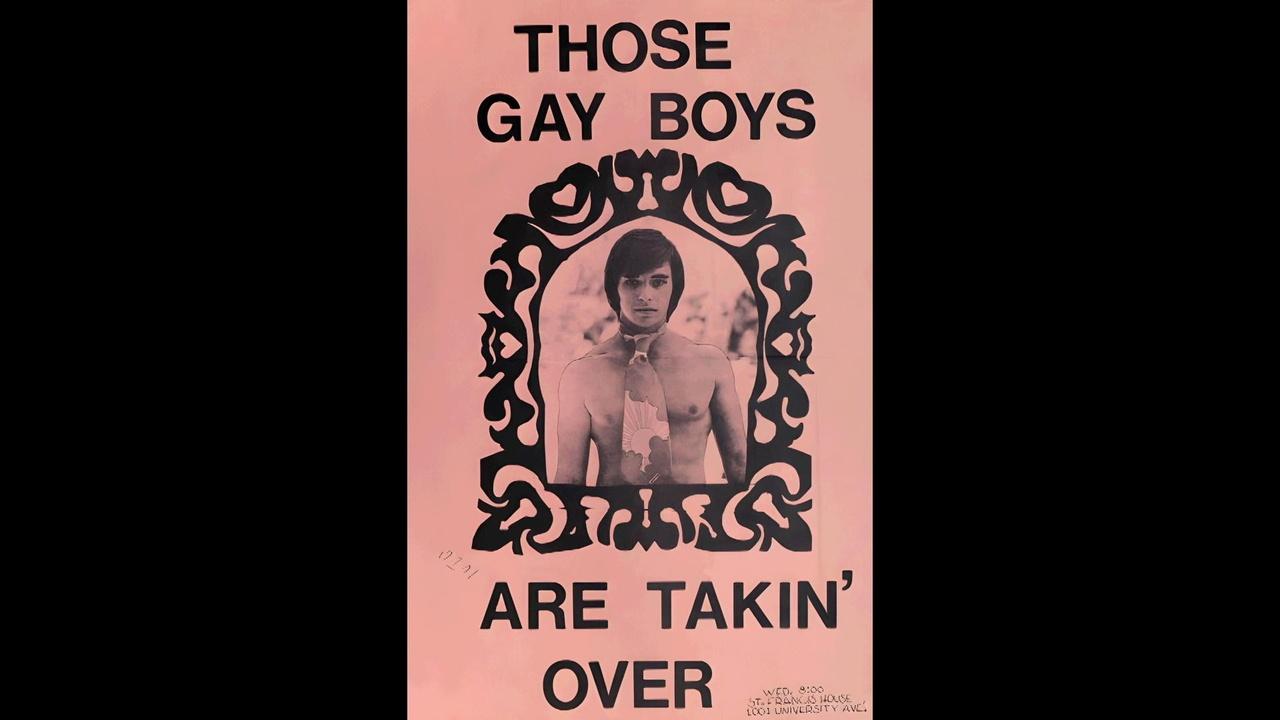

Scott Seyforth: They started by calling themselves the Madison Alliance for Homosexual Equality.

§ §

Dick Wagner: The Madison Alliance for Homosexuality Equality was recognized as the first gay organization in Wisconsin.

Scott Seyforth: Just months after Stonewall, they were on the local news channel. You know, out queers are on television in the state of Wisconsin. In March, they hold the first publicly announced gay dance. They had the first protest.

Narrator: The group protested outside a Madison theater playing the film The Boys in the Band.

Dick Wagner: They felt it depicted self-loathing homosexuals. The early activists particularly found that despicable as a portrayal.

Film: You’re a sad and pathetic man. You’re a homosexual, and you don’t want to be. But there’s nothing you can do to change it.

Dick Wagner: While they were picketing, they heard shouts of “faggots” from young kids in cars driving by. But it was very brave to do that kind of public action. To go out and be visible homosexuals in the community. You found other people who were willing to be out, and that gave you strength.

Narrator: By 1971, the group had adopted the name “the Gay Liberation Front” and had been attracting new members across campus, including an anti-war activist named Judy Greenspan.

Judy Greenspan: I can’t count the number of times I was tear gassed.

[explosion, shouting]

There was, like, a revolutionary spirit on campus. We were all part of this progressive movement, and it was a massive movement.

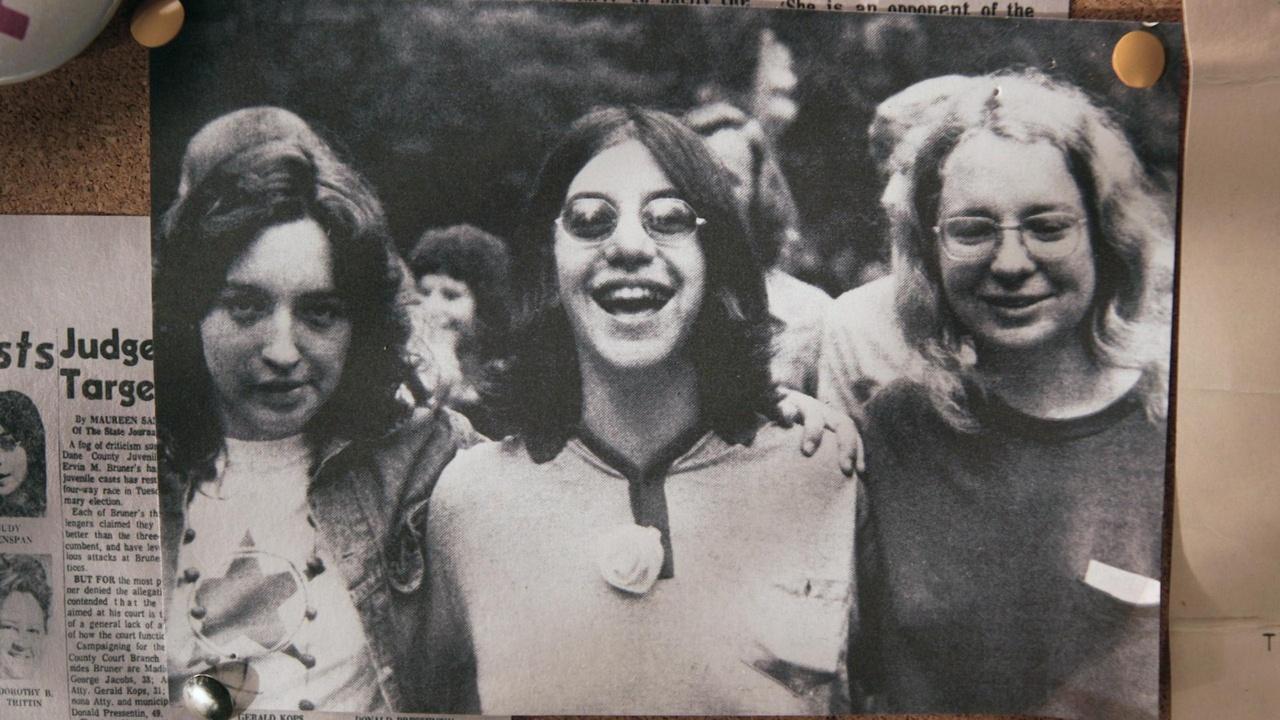

Narrator: A New Jersey native, Judy Greenspan came to school at UW-Madison drawn by the anti-war movement. Finding like-minded people fighting for a cause, Greenspan was still looking for something more. Searching for other lesbians…

Judy Greenspan: So, I found out where the Gay Liberation Front was meeting. I went to a meeting, and they were literally about forty-five young men… and one woman. I just said, “This is ridiculous.”

Narrator: Determined to build a sisterhood, Judy Greenspan and a friend began to post fliers on campus, calling for lesbians to come together. What Greenspan did not expect was the reaction from comrades in the anti-war movement when they saw the fliers.

Judy Greenspan: People would say, “Oh, what are you organizing?” And they’d look at it, and their jaw would drop. And then, they’d sort of walk away. The amount of homophobia in the anti-war movement was, I thought was pretty deep. I don’t see the dichotomy between being a political person fighting for social change and being queer. I don’t; I think they’re– they’re together.

Narrator: Greenspan’s grassroots organizing helped form the group that would become known as Madison Lesbians.

Judy Greenspan: We didn’t have the community. We had to build the community. And we just did it the best that we could. You know, could somebody have done it better? Probably.

[laughs]

But we did it; We did it.

[laughs]

Narrator: Together, Madison Lesbians and the Gay Liberation Front traveled around the state, working with emerging gay organizations at other college campuses on LGBTQ+ issues. But at home, they would find themselves locked out when students at Madison East High invited Greenspan to speak.

Dick Wagner: The principal ruled that “No, out lesbian Judy Greenspan couldn’t come and speak.” In fact, the Madison Principals’ Council ruled that they wouldn’t allow any homosexual speakers in the high schools.

Judy Greenspan: And the school board totally backed him up on it. Everybody would say, “Oh, yeah. “I mean, that’s a no-brainer. “Gay people are sick; They’re ill. “It’s illegal. Can’t let them into schools.”

Narrator: The ban not only kept gays and lesbians out, but also put any closeted students or teachers at risk. The Madison Lesbians and activist Judy Greenspan decided to take a stand for gay rights.

Judy Greenspan: We fought back by running an openly lesbian candidate for school board. And I said, “Oh, yeah, I’ll do it.” So, as a lesbian, I could not go into the schools. I couldn’t speak to the students. I couldn’t get through the door. But as a candidate, they would not be able to deny me entrance.

Dick Wagner: As a candidate, she would appear on forums that were in the high school and be able to debate. It was a very inventive way to challenge the ruling of the principal.

Judy Greenspan: We were not running to be part of the political system. But we really ran as a way to protest what we thought is a horrible injustice.

Narrator: Greenspan would not win the 1973 school board election. But would make history as the first out lesbian to run for public office in America. And the first in a long line of LGBTQ+ people who sought office in Wisconsin.

Dick Wagner: Wisconsin is the only state to have elected three out congresspeople. Steve Gunderson, a Republican. Mark Pocan, a Democrat. And the first U.S. out Senator, Tammy Baldwin.

Narrator: For Judy Greenspan, it was about seeking justice. Taking a public stance for those who couldn’t.

Judy Greenspan: It was definitely one of the proudest things that I have done in my life.

Radio Host: Welcome once again to Gay Perspective, the radio voice of Gay People’s Union. We’re going to be interviewing a young lady who happens to be a homosexual. But first, let’s have a little music.

§ §

[cue ball strikes]

Narrator: The nation’s first LGBTQ+ radio program, Gay Perspective, hit the airwaves in 1971.

Host: This program will discuss a gay perspective.

Narrator: Produced in Milwaukee by the activist organization Gay People’s Union to serve a community finding its voice.

Host: Today, throughout the country, homosexuals are clamoring for their rights.

Michail Takach: Within 10 years of the Black Nite Brawl, Milwaukee had really come together as a community of LGBT people looking to not just find each other socially but to socially activate and organize. One of the organizations that came out of this era was Gay People’s Union.

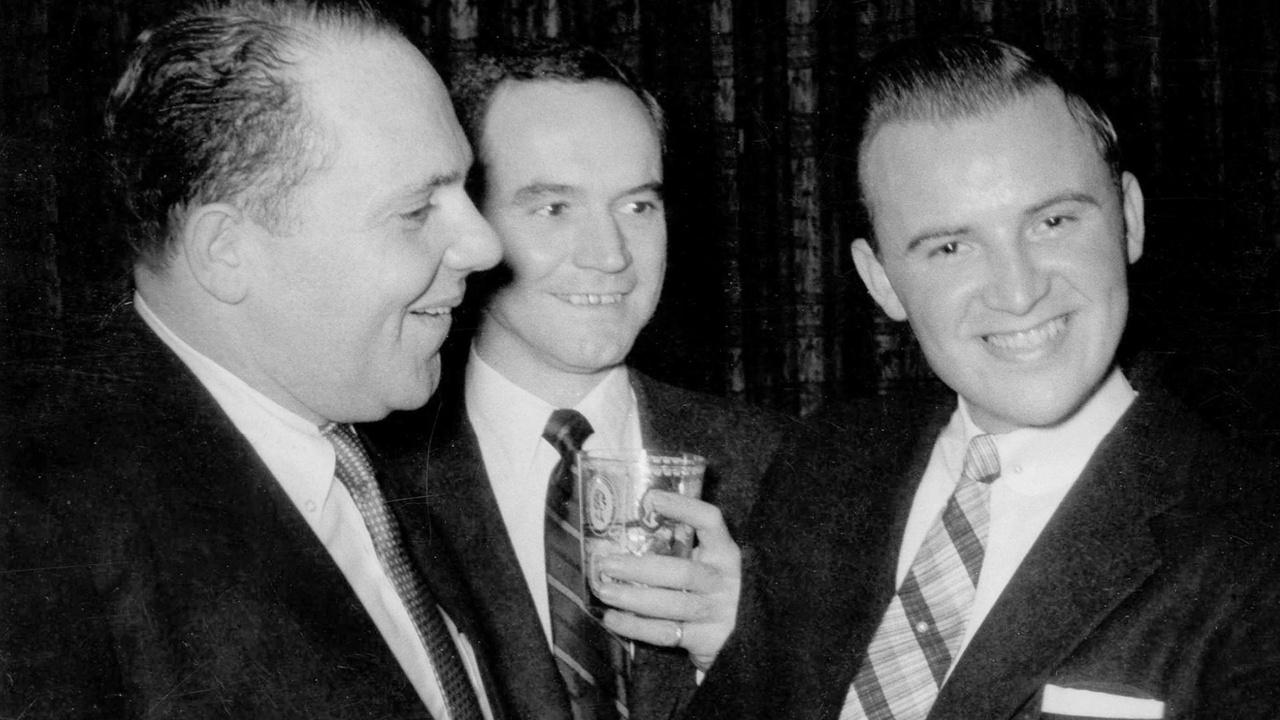

Narrator: Gay People’s Union was founded in 1971 by two openly gay men, Eldon Murray and Alyn Hess.

Brice Smith: Being able to be openly gay, they were able to do so much work for the community and for the Gay Liberation Movement.

Michail Takach: This was a time where people could be fired from their job just for being gay.

Narrator: Eldon Murray, who served in Korea, then worked as a stockbroker, was quoted, “My clients didn’t care “as long as I made money for them. “I could stand up and be openly gay when few people could.”

Standing alongside him was gay rights crusader Alyn Hess, a landscape architect turned social activist.

Michail Takach: They established the first gay crisis hotline in Milwaukee. They opened the first gay community center. And they also fought with local newspapers about printing the names of people arrested for disorderly conduct and got them to end that policy, which was a lifesaver for many, many gay people.

Dick Wagner: They were remarkable pioneers in the fight for gay rights.

Michail Takach: They really changed Milwaukee for the better.

Narrator: Along with their radio program, Gay People’s Union established GPU News, A newspaper written by and for LGBTQ+ people. The publication found a national audience and introduced readers to singular voices, like columnist and trans pioneer Lou Sullivan.

Brice Smith: Lou Sullivan wrote articles on historical figures. People with whom he identified. People who are assigned female at birth but had lived as men. He very much recognized and appreciated how important history is to an individual’s identity.

Narrator: Lou Sullivan grew up in Wauwatosa, Wisconsin. His fourth birthday party was a memorable day.

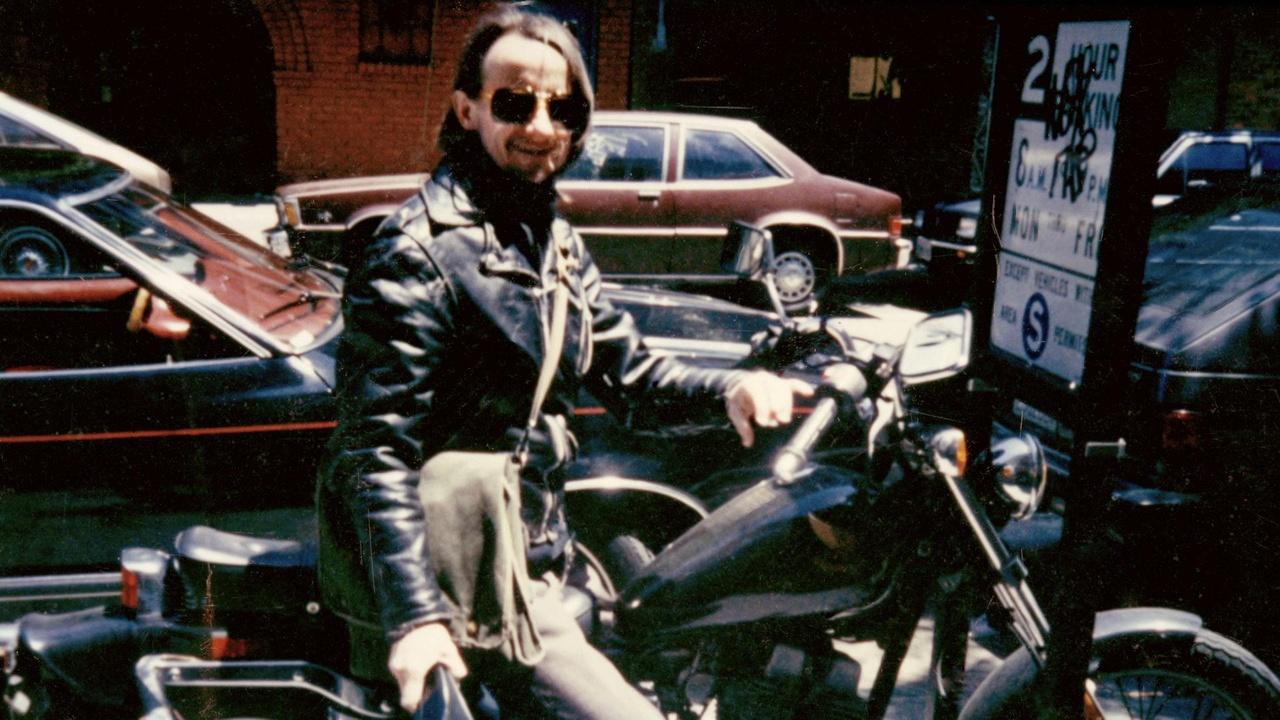

Brice Smith: It was a Davy Crockett-themed birthday party. Lou always remembered that when he put on that Davy Crockett costume, he really felt like he was Davy Crockett. His life intersected with so many of the key moments in the Baby Boomer generation. He liked to brag that he was the most “Beatled” kid at his school ’cause he knew more about The Beatles than anyone. His idol became Bob Dylan. And he would wear these cowboy boots, bell-bottom jeans. As he moved into his early twenties then, his idol became, incidentally, his namesake.

[laughs]

The rock star Lou Reed.

Narrator: Lou Sullivan donned a leather jacket, embraced a new identity, and began to live life as a gay trans man.

Brice Smith: A lot of people assigned female at birth were really into these pop culture icons: the Beatles, Bob Dylan, Lou Reed. But what was different with Lou is that he both wanted these men, and also wanted to be them simultaneously. So, the lines between desire and identification were very blurred for him.

Narrator: Sullivan underwent a mastectomy and received hormone therapy while considering a gender-affirming surgery for years. And although the surgery was an established medical practice by the 1970s, Lou Sullivan’s unique request was denied.

Lou Sullivan: I was told that my case was too unusual, that they had never heard of a female-to-male who wanted to be a gay man, that they did not want to be the first to operate and deal with such a person.

Brice Smith: His youngest brother, Patrick, died in a motorcycle accident. This is when he realized, “You know what? “We don’t have that long. “If I were lying on my deathbed, “I would regret not transitioning. This is something I’ve got to do.”

Narrator: For nearly a decade, Sullivan pleaded the case to medical professionals that someone could be a trans man and also a homosexual. And in 1986, he finally prevailed. A doctor in San Francisco agreed to perform the gender-affirming surgery, charting new territory in the medical field.

Brice Smith: As soon as he found someone willing to help him, then he just shouted from the rooftops and spread the word. It spread like wildfire through the trans community.

Narrator: Lou Sullivan published a groundbreaking guidebook to help both doctors and trans people bridge the gap between sexual orientation and gender identity. Sullivan also shared first-hand experiences with the trans community through his female-to-male newsletter.

Lou Sullivan: As long as no one else is talking about it, it’s going to be forever silent, and no one is going to hear about it. I wanted to connect with people in feeling like an honest person with people. I just don’t see any reason to hide it.

Brice Smith: Lou was able to be there for countless trans men. There’s just nothing like moving in the world and having everyone see you as you know you should be seen, as you have known yourself to be for so long.

Lou Sullivan: I spent so many years trying to figure out a place in society. Finally, I could breathe. It felt so good.

Dick Wagner: People who had decided to lead their authentic lives in Wisconsin had a sense that there were possibilities,

[cheering]

including making marriage equality a national reality.

Patrick Farabaugh: Before marriage equality became a big national movement, one of the first places to actually challenge for the right to marry was Milwaukee in the ’70s.

[disco music]

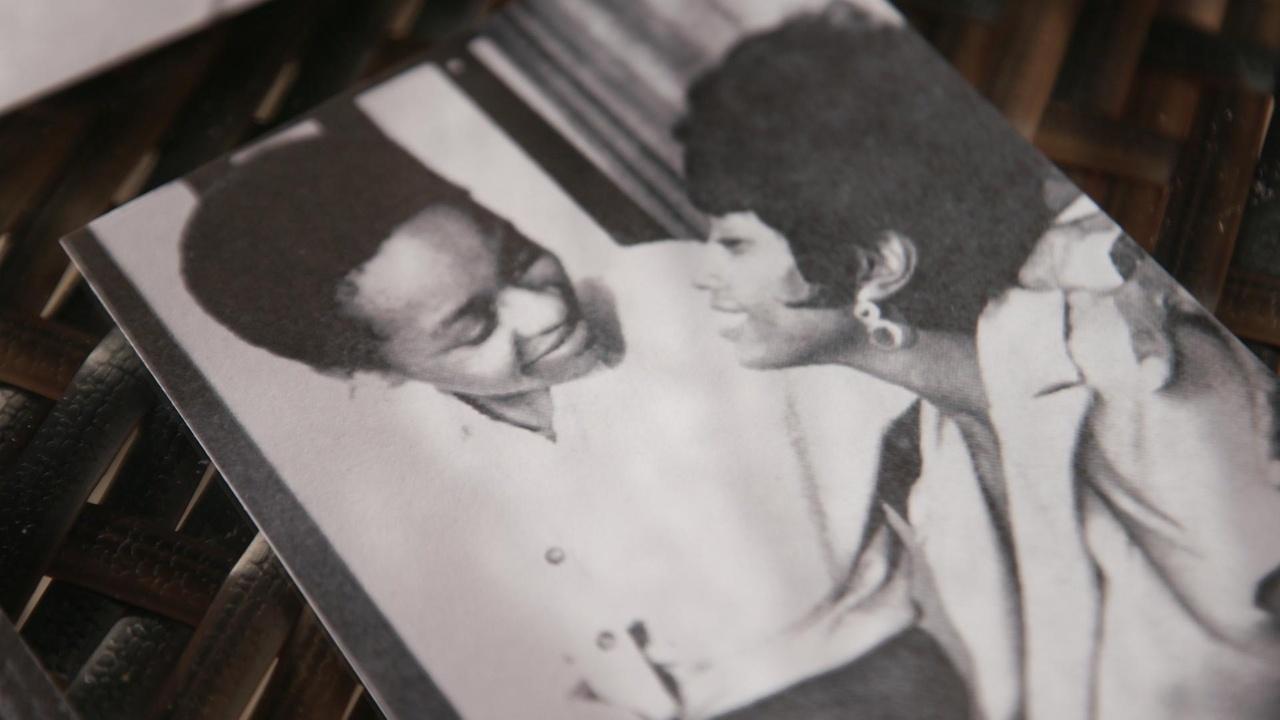

Narrator: In 1971, Milwaukee natives Donna Burkett and Manonia Evans went to the county clerk’s office to apply for a marriage license. The young lesbian couple was promptly denied.

Reporter: When did you decide to take these steps, and how did you come about that decision?

Manonia Evans: Well, we decided this summer that we would like to get married, and there shouldn’t be any reason why we shouldn’t be able to get a license.

Narrator: A preacher’s daughter, Manonia Evans was a junior in college when she met housing rights activist Donna Burkett in a gay bar in Milwaukee’s north side. Two years later, they would make history.

Kristen Whitson: The act of applying for a marriage license as two women got a lot of media attention.

Narrator: Jet magazine ran a feature on the young Milwaukee couple. Their story was also picked up by lesbian and gay publications from around the country.

Patrick Farabaugh: They were at the front of the movement at that period in time.

Dick Wagner: The couple was willing to be public about their wish to be married, which was significant.

Kristen Whitson: It really was a big part of the public understanding of what same-sex couples wanted, which was really just what everybody else had.

Radio Host: Donna and Manonia, welcome to Gay Perspective. And we welcome you to our program to express your views.

Manonia Evans: We’re people just like anybody else. And we have feelings, too.

Donna Burkett: I love her, and I don’t care who knows. It’s not something that I want to hide. Love is not meant to be hidden, and I won’t hide it.

Patrick Farabaugh: Donna Burkett was like, “Yeah, well, “that’s what you do when you love somebody. You go, and you marry them.”

Dick Wagner: She felt that she had this right and that she wasn’t about to accept being denied it.

Narrator: Burkett and Evans challenged for the right to marry. They filed a federal lawsuit on the grounds that the denial of marital benefits did not afford the couple equal protection under the Constitution, a legal argument ahead of its time.

Donna Burkett: They shouldn’t have any laws on who you can marry or who you can’t marry. That’s none of their business. If we’re living together, we’re sharing our money, then we should have some protection.

Kristen Whitson: Donna and Manonia said that they felt they were missing out on tax benefits by not being allowed to marry, which is true. That was a significant part of the fight for marriage equality was to have the same civil rights that every other married couple had.

Narrator: The young couple’s visionary legal challenge regarding marital benefits was a predecessor for legalizing same-sex marriage nationally 44 years later in 2015.

[cheering]

Narrator: A landmark civil rights case granting equal protection to same-sex couples. And though Burkett and Evans’ lawsuit was eventually dismissed on technical grounds, and the couple was refused a legal marriage, their love for each other would not be denied.

Reporter: Whether or not they obtain a marriage license, they will be married Christmas Day at St. Nicholas Church in Milwaukee.

[cheering]

Pastor: Well, God loves all people. Here are two people, and He blesses their love for each other. And so, that’s what His church is about is blessing this union, which is sacred of itself.

Narrator: Burkett and Evans’ story would ultimately draw national attention to marriage equality, making a statement not only about love, but also a statement about civil rights for LGBTQ+ people.

Kristen Whitson: Queer people who have had to struggle with fewer rights than their heterosexual counterparts had never thought of even trying to apply for a marriage license before they read about Donna and Manonia trying to do it. And that was an idea planted in their heads as something that they could fight for in the future.

Dick Wagner: It was something that would have been unthinkable before Stonewall.

Manonia Evans: We want more out of life. This is something really worth fighting for.

[delicate piano]

[poignant piano music]

Dick Wagner: In Wisconsin, you repeatedly had lesbian and gay publishers and editors who felt the need to have these gay publications here. Gay Endeavor, Escape, In Step, Hag Rag, Wisconsin Light. They were an important part of building community in this state.

Narrator: These publications often reflected and spoke to specific groups within the growing LGBTQ+ community.

Kristen Whitson: “Bi” question mark, “Shy” question mark, “Why” question mark, as in “Why are you shy to be bi?” It was an organization to recognize visibility and advocacy for bisexuals. They published a newsletter called Bi-Lines.

Dick Wagner: It had a little fun in its pages in that regard. But again, it was an example of the need for an expression of the community and a physical manifestation of the community in a publication.

Patrick Farabaugh: You needed something in community that could take care of and prioritize queer voices in a way that supported them, created space for them to explore their identity, and just educate them around cultural issues as basic as literally just finding each other.

[electronic pop music]

Dick Wagner: Leaping La Crosse News was a smaller newsletter that was published by the lesbian community in La Crosse. It was published for decades in that area.

The Leaping La Crosse News was established in 1979, and became an ongoing record of vibrant lesbian life outside of Wisconsin’s larger cities.

Mary O’Sullivan: It was the way a lot of women found us. And they’d say, “Holy smoke! I didn’t know there were any lesbians in La Crosse.” They were just astonished that there could be anything happening in this little town of 50,000 people.

Narrator: The editor of the newsletter, Mary O’Sullivan, was a college instructor who grew up in a supportive family. In La Crosse, she hoped to build that same support for other women.

Mary O’Sullivan: Pretty soon, we had a thriving community of women who all knew each other and socialized.

The Leaping La Crosse News opened a whole new world for fellow lesbians, revealing an underground culture that stretched well beyond the bar scene.

Mary O’Sullivan: If you get lesbians together, the first thing they are going to do is organize potlucks and groups.

[chuckles]

Narrator: The monthly newsletter connected the women with social events, ran news stories impacting the lesbian community, and even covered entertainment and sports.

Mary O’Sullivan: Just being able to pick up an eight-page newsletter that talked about people like them and with like interests, that was a huge thing.

Narrator: In 1979, Mary O’Sullivan and some of her friends discovered that a local formal wear shop had been stockpiling discontinued tuxedos for years. Inspiration soon struck!

Mary O’Sullivan: We could buy these tuxes for like five bucks for the whole thing, and we could have a formal wear party.

For some, it was the prom that never was. For others, a great night out, akin to a costume party. But for all, a celebration, a place of acceptance.

Mary O’Sullivan: We weren’t trying to be men or masculine. We were just trying to question the every day and the accepted. It was an outrageous thing to do. But that was a really empowering kind of experience.

Narrator: The annual tux party continued for a decade, helping La Crosse to later be named the fifth best place in the U.S. for lesbians to live, according to Girlfriends magazine in 2002. The tight-knit group in the small Wisconsin community had created a place all their own.

Mary O’Sullivan: It was like a big family. And for some women, we were their family because they got kicked out. The world wasn’t all that safe then.

Kristen Whitson: Queer people often feel more comfortable with other queer people. They didn’t have to worry about being bullied or harassed. They know that their experiences are not singular, that they are not alone.

Narrator: Often closeted, people all across Wisconsin were finding each other. Connecting in a world that had marginalized them. Persevering in building meaningful and enriching lives.

Mary O’Sullivan: We had a real world, too.

Narrator: Yet, by the 1970s, there were still no laws in America that protected those lives. Homosexuals were often regarded as criminals. In Wisconsin, the pursuit of equal rights would bring together an unlikely group on the cusp of making history.

Dick Wagner: It was time to speak out for homosexuals.

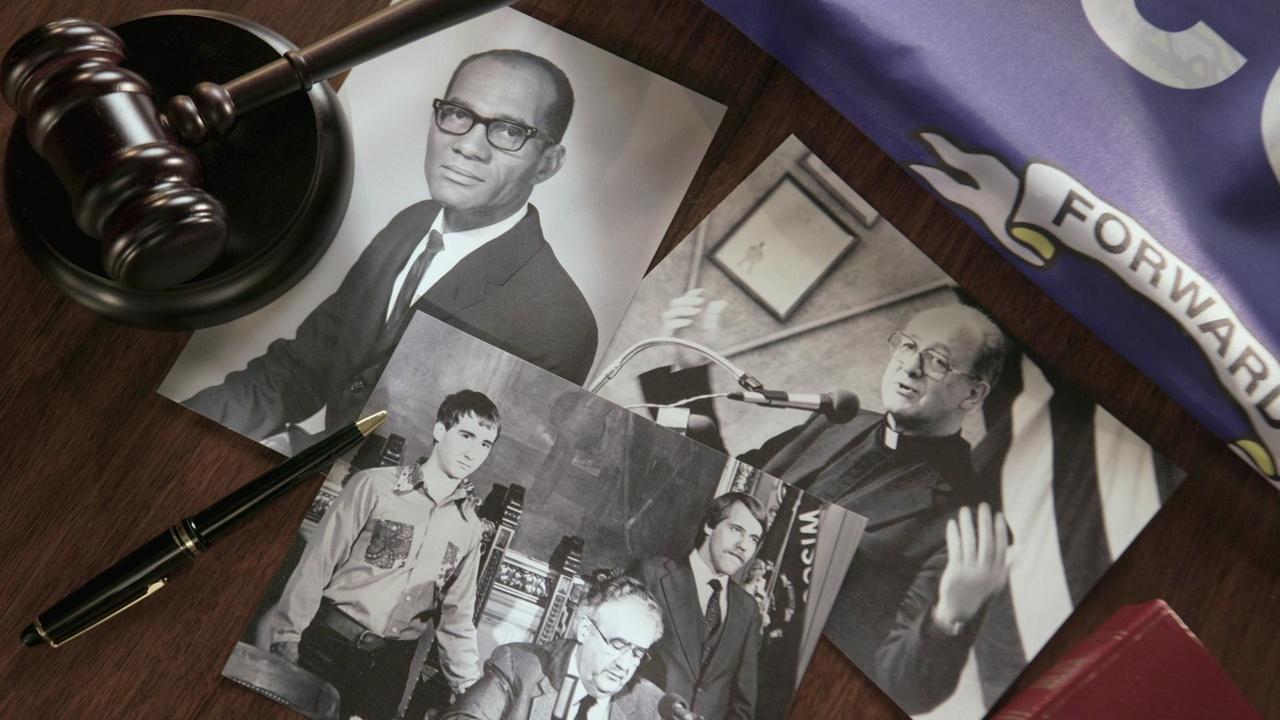

Narrator: Assemblyman Lloyd Barbee was an ally to the gay rights movement. Before his time in the Legislature, Barbee was a civil rights attorney who fought housing discrimination and led the effort to desegregate Milwaukee’s public schools. Elected to the Wisconsin State Assembly in 1964, he was the only African American in either house of the Legislature.

Dick Wagner: Barbee felt deeply about the American promise that should be extended to all who were a part of society. In his view, not only African Americans, but homosexuals deserved rights, as well.

Narrator: Barbee was a bold pioneer for social reform and was the first legislator to challenge the sex laws in Wisconsin, calling to decriminalize homosexuality and legalize gay marriage.

David Clarenbach: He was frequently referred to in the press as “The Outrageous Mr. Barbee” because he introduced these bills that were way, way before their time. But thank goodness he did.

Dick Wagner: He believed in introducing legislation to educate folks. And he was not shy about this.

David Clarenbach: He stuck to his principles and objectives. And he took a lot of flak because of that.

Lloyd Barbee: I think that homosexuals should not be harassed and beaten down and brutalized and insulted. And we should not tolerate it.

Narrator: Morality laws that had been on the books since the 1800s criminalized a variety of sexual acts; applying to everyone, not just homosexuals.

David Clarenbach: Most people didn’t recognize how restrictive Wisconsin statutes were in criminalizing sex acts that were pretty commonplace. Things like oral sex, even between a man and a woman who were legally, lawfully married, was a criminal offense in Wisconsin.

Narrator: Yet, these morality laws were selectively enforced; a means to target and prosecute homosexuals.

David Clarenbach: It was an excuse for rooting out gays and lesbians and bisexuals in the state.

Narrator: In 1974, at the age of 21, David Clarenbach was the youngest member elected to the Wisconsin State Assembly.

David Clarenbach: I certainly had known that I was gay before I was elected to public office. But it wasn’t a time when I felt comfortable to come out, especially as an extraordinarily young candidate.

Narrator: Clarenbach grew up in Madison, his family heavily involved in social reform movements. His mother, Kathryn, was a co-founder of the National Organization for Women, the largest feminist group in America. In the Legislature, David Clarenbach teamed up with Lloyd Barbee.

David Clarenbach: Lloyd Barbee was not just my role model and my mentor, but he really was a prophet.

Narrator: Together, they drove legislation to completely overhaul the sex laws in Wisconsin. But the two men were unsuccessful in gaining enough support from their fellow lawmakers to advance such broad reform.

Lloyd Barbee: It’s not the job of the state…

Narrator: In 1977, Lloyd Barbee left the Legislature.

Dick Wagner: Barbee passed the baton on sex reform leadership to David.

Narrator: Rather than introducing bills calling for sweeping change, Clarenbach instead focused on single-issue legislation. He would land on the Consenting Adults Bill, a law which would repeal the morality laws that criminalized homosexuality.

David Clarenbach: They want those in violation of those statutes put in jail.

Dick Wagner: The basic premise of homophobia is that homosexuals are criminals.

Narrator: The Consenting Adults Bill faced an uphill battle, taking Clarenbach years to advance it.

David Clarenbach: Each session, it gained a little more traction. It kept moving forward. And then, finally, in 1981, the Consenting Adults Law came to a vote in the Assembly, and we lost it by one vote.

Narrator: A narrow defeat. But with bipartisan support, hope was still alive.

David Clarenbach: This was a question of momentum.

Dick Wagner: The bill had both Republicans and Democrats supporting it.

David Clarenbach: It proved a legislator could cast a vote for gay rights, and not feel that they’re jeopardizing their own reelection campaign.

Narrator: In Wisconsin, an opportunity was within reach.

[pounds gavel]

Clarenbach signed on to co-sponsor a nondiscrimination gay rights bill, which would add sexual orientation to protected nondiscrimination categories such as race, age, and religion, ensuring someone could not be fired from their job or denied a mortgage for being homosexual. For the bill to succeed, an expansive coalition of support would need to be built from the ground up.

David Clarenbach: The gay rights movement would not have advanced if it weren’t for gay bars and a gay press.

Narrator: The gay press kept people informed, tracking the progress of the bill through the Legislature, while gay bars became a place for people to organize, creating an outreach effort to build public support for the bill. However, to convince some lawmakers who were on the fence, the gay rights movement needed to gain an unlikely ally: one that had condemned homosexuality for centuries.

David Clarenbach: We needed to get religious support from the mainstream religious community.

[nuns praying]

Narrator: The leader in the outreach effort was Leon Rouse, a UW-Milwaukee student activist who organized a supportive group of pastors and rabbis.

Dick Wagner: You had to knock on doors and say, “Tell us what you think about homosexuals and about homosexual issues.” It took some bravery to start knocking on those doors.

Narrator: Rouse was short of a vital endorsement. The head of Milwaukee’s Catholic Church, Archbishop Rembert Weakland. After weeks of attending mass, Rouse finally approached the archbishop with his pitch.

Dick Wagner: It’s not whether homosexuality is being approved. It’s whether discrimination is tolerable.

David Clarenbach: Could discrimination and bigotry be tolerated against any group in our society? That question turned the tide.

Narrator: Archbishop Weakland pledged his support.

Dick Wagner: Archbishop Weakland said that “We have to see gay people “not as an enemy to be battered down, but as persons worthy of respect and friendship.”

David Clarenbach: It was decisive. Earth-shattering that a Catholic Archbishop would advocate in such a public way.

Narrator: In December of 1981, the gay rights nondiscrimination bill passed in the Wisconsin Assembly. Moving on to the state Senate for a final vote.

David Clarenbach: It was going to be close, and we had one shot at this.

Narrator: On that fateful day, the LGBTQ+ community would not stand alone.

David Clarenbach: Well, to be able to sit in the Senate chambers and see the galleries packed with nuns and priests and other religious leaders sent the message that it was a moral statement to oppose discrimination and bigotry against any group in our society.

Narrator: The nondiscrimination bill passed in the Senate with religious backing and bipartisan support. On February 25, 1982, the nation’s first gay rights legislation was signed into law by Wisconsin Republican governor Lee Sherman Dreyfus.

Dick Wagner: It was an exciting moment.

David Clarenbach: We accomplished something that no one thought was possible. No one would have guessed in 1982 that of all states, Wisconsin would be the first state in the nation to enact civil rights protections for gays and lesbians. But Wisconsin became known as “the gay rights state.”

Crowd chanting: Wis-con-sin, gay rights state, Wis-con-sin, gay rights state,

Narrator: Within a year, Wisconsin passed the Consenting Adults Bill, followed by three additional landmark pieces of legislation protecting civil rights. All starting with a vision for the future, the courage to bridge a gap, and the belief in equality.

David Clarenbach: You did not have to be a female to believe in equal rights for women any more than you needed to be LGBT or Q to be supportive of gay and lesbian civil rights. Civil rights are for everyone.

[poignant piano]

[heart monitor beeping]

Dave Iverson: Wisconsin registered its first official case of AIDS, an epidemic that has resulted in nearly 500 deaths, mostly among homosexual men.

David Clarenbach: The AIDS crisis hit like a bolt of lightning.

Dick Wagner: We just felt that we were under siege. Seeing our community dying around us.

Narrator: Among that community was Alyn Hess, co-founder of Gay People’s Union. And in San Francisco, Wisconsin native and trans pioneer Lou Sullivan.

Lou Sullivan: I discovered that I had AIDS. I was diagnosed with AIDS.

Brice Smith: It was just heartbreaking, gut-wrenching. So many obstacles to overcome in order to transition, only to be diagnosed as having AIDS.

Dick Wagner: They tried to deny him to live as a homosexual, but he would die as a homosexual.

Narrator: From the outset of the AIDS crisis, a second epidemic was born; one of fear.

We got a lot of homophobia floating around, and it doesn’t surprise me.

It’s almost like being a leper in olden times. You go put them in the dirtiest parts of the village and keep them away from society.

[heart monitor beeping]

Person with AIDS: I wouldn’t even feel free to hug somebody. Just because they got the scare in you, I guess. I don’t know.

[monitor beeping]

Narrator: As the disease spread throughout the country, Wisconsin remained committed as the “gay rights state.” In 1983, newly-elected governor, Tony Earl, formed the Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues. A group that helped lay the groundwork for a public health response to the deadly disease.

David Clarenbach: Governor Earl was such an outspoken supporter of the gay and lesbian community

Narrator: By 1985, he signed legislation that protected the confidentiality of people who tested for the virus. And in 1990, the state’s next governor, Tommy Thompson, signed the AIDS Bill of Rights, which prohibited insurance companies from discriminating against people with AIDS.

Anchor: The bill is believed to be the first of its kind in the country.

David Clarenbach: People weren’t going to be fired from their jobs or denied health insurance coverage because of their HIV status.

Narrator: Legal protections were guaranteed in Wisconsin. But with no cure, the deadly crisis continued into a second decade.

Dave Iverson: Reporting on AIDS is a little like reporting on war: a grim listing of the latest statistics.

David Clarenbach: Unfortunately, ongoing, continuing crises are easily forgotten.

Protester: We’re here today to protest the city of Milwaukee’s callous indifference to the AIDS crisis.

Narrator: The next generation of activists fought public fatigue with confrontational and attention-grabbing actions.

Anchor: AIDS activists passed out more condoms and pamphlets at a Milwaukee high school this morning.

David Clarenbach: Organizations like ACT UP kept the spotlight focused on the AIDS Crisis and how it was affecting the real lives of real people.

Narrator: In Madison, ACT UP led a massive protest over conditions for inmates with AIDS. The event brought hundreds to the Capitol, including future advice columnist Dan Savage and longtime activist Judy Greenspan.

Judy Greenspan: AIDS in prison is a death sentence. I visited a lot of prisons. I met with a lot of prisoners with HIV. They were not getting medications. They were being segregated.

Dick Wagner: All they got for lunch and dinner was peanut butter and jelly sandwiches that would be shoved at them.

Narrator: ACT UP responded with a special delivery to the State Capitol. Hundreds of peanut butter sandwiches and a series of public protests.

[protester calls out on megaphone]

Judy Greenspan: It was an in-your-face action to say, “Look, stop this. It’s outrageous”. How they were treating prisoners with HIV was absolutely horrible.

[crowd chanting “Shame, shame, shame!”]

Dick Wagner: The activism and the legislative victories were an effort to try and do something positive in the face of what was still a terrible epidemic for the state to face.

Kristen Whitson: There’s not a silver lining to it. But if there was one, it’s that the LGBTQ+ community was united, galvanized, and motivated.

Narrator: The spirit of activism continued into the 1990s. Protestors in Wisconsin led a nationwide effort to push back against the military’s refusal to accept gays and lesbians. In 2011, LGBTQ+ people could finally serve openly. And in 2022, Senator Tammy Baldwin guided federal legislation that was signed into law, protecting same-sex marriage, part of the ongoing pursuit of civil rights.

Kristen Whitson: People have fought for it, have overcome the obstacles. But LGBTQ+ rights are not static.

Kai Pyle: That fight is still incredibly real and ongoing, but there’s hope.

Dick Wagner: The progress has just been amazing.

Mary O’Sullivan: Being able to publicly say the most important person in my life is this person right next to me, and we’re going to have a wonderful damn life for all the years that we’ve got.

Brice Smith: Times have changed dramatically.

[laughs]

Narrator: Through the struggles, through the victories, Wisconsin history was written.

David Clarenbach: History is made by individuals.

Ashley Brown: The individuals, they come out of, they reflect Wisconsin history.

Michail Takach: Wisconsin is fortunate to have a lot of LGBTQ heroes throughout its history.

Dick Wagner: They had refused to be ashamed of who they were. It was just powerful. They were remarkable people. Brave people.

§ §

Announcer: Funding for Wisconsin Pride is provided by Park Bank, S.C. Johnson, Greater Milwaukee Foundation, Evjue Foundation, the charitable arm of the Capital Times, CUNA Mutual Group, New Harvest Foundation, West Foundation, Paula Bonner and Ann Schaffer, La Crosse Community Foundation, MG&E Foundation, Rogers Behavioral Health, with additional support from and with support from Focus Fund for Wisconsin Programs, and Friends of PBS Wisconsin.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us