Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings:

Look at how Black students are doing. It is… terrible.

Prof. Ion Meyn:

Whatever efforts there have been by the federal government to create integrated schools have not worked.

Dr. Tremayne Clardy:

Education is the conduit to freedom.

Sarah Shaw:

We have a lot more work to do.

Murv Seymour:

Wisconsin.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings:

We’re a microcosm of the nation.

Classroom teacher:

We want to create change.

Murv Seymour:

A conversation about race and education in this state.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings:

It is a complex one. We’ve never given full education access to everyone.

Murv Seymour:

Author and retired University of Wisconsin Education Professor, Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings, travels the world learning, teaching, and training people about education.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings:

It’s Thomas Jefferson who says, “Listen, we are not gonna be able to maintain a democracy unless the common folks are educated.”

Dr. Christy Clark-Pujara:

It goes all the way to the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

Murv Seymour:

Dr. Christy Clark-Pujara is a UW-Madison history professor, and also works with the Madison Organization, Nehemiah. She’s an instructor in its Justified Anger “Black History for a New Day” course. Nehemiah focuses on strengthening the African American community in Wisconsin. The nine-week course teaches people about race, history, and justice. She and Ladson-Billings help explain why the playing field of education began to take shape out of balance across the country, including here in Wisconsin.

Dr. Christy Clark-Pujara:

The laws against teaching enslaved people to read actually come into play after the founding of the nation, in response to enslaved people doing things like forging fake passes.

Murv Seymour:

Written by their owners, passes were required for slaves to leave the plantation for extra work or errands.

Dr. Christy Clark-Pujara:

When we’re talking about access to education, post-slavery, you just have cities, states, and counties not investing in the education of Black people, who are taxpayers. They would have inferior school buildings, inferior materials, inferior books, or notebooks, right? The teachers were paid less. And so, it was an active disinvestment. My father was functionally illiterate. His family was poor, and he was sharecropping cotton most of his life, and his labor was essential to his family’s survival, and the school that he could attend was underfunded.

Murv Seymour:

During the civil rights era, Milwaukee was the epicenter of protests, demanding compliance to end continued segregation in schools.

Dr. Christy Clark-Pujara:

We tend to think about the Civil Rights Movement, like the institution of slavery, as something that is uniquely Southern, and it was not.

Murv Seymour:

While the US Supreme Court’s Brown versus the Board of Education ruling in the late 1950s ordered all US schools to desegregate, Milwaukee and other parts of the state, like much of the nation, didn’t do so for decades.

Dr. Christy Clark-Pujara:

The schools in Milwaukee are not in line with Brown versus the Board of Education until 1979.

Reggie Jackson:

The city of Milwaukee’s public school system decided, “Well, we’re gonna build new schools, but we’re gonna build them on the south side, which is primarily the white part of town, right?”

Dr. Christy Clark-Pujara:

The schools that Black people have access to were severely underfunded.

Prof. Ion Meyn:

What you saw in Black communities was a continual kind of decline in the tax base, and the ability to support public education in those communities.

Murv Seymour:

A declining tax base due to declining property values in housing like this in Milwaukee.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings:

Housing policy is education policy. You go to the schools in your neighborhood, and we tend to fund schools through property taxes. Better than 60% of Black and brown kids still go to segregated schools.

Murv Seymour:

Schools in the Milwaukee metro area are more segregated for Black and white students than any other metro area of the country. That’s comparing Milwaukee schools to those in the surrounding counties of Ozaukee, Washington, and Waukesha.

Prof. Ion Meyn:

Whatever efforts there have been by the federal government to create integrated schools have not worked.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings:

There are many white children who go to all-white districts, and nobody says, “Oh, this is a segregated district.” They say, “This is a good district.” If you look at performance, Black and brown kids continue to lag.

Murv Seymour:

Those students test below white students in math, in the early grades, and it’s not just math.

Teacher in classroom:

It speeds over a hundred miles an hour.

Murv Seymour:

If there’s one indicator of how students will perform…

Sarah Shaw:

Reading proficiency is important across the races.

Murv Seymour:

It’s their ability to read by 3rd grade, and state assessments show that just one year later in the 4th grade, reading scores for Black and Hispanic students also lag.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings:

The most revolutionary thing we could do is teach these kids how to read. Whoa!

Murv Seymour:

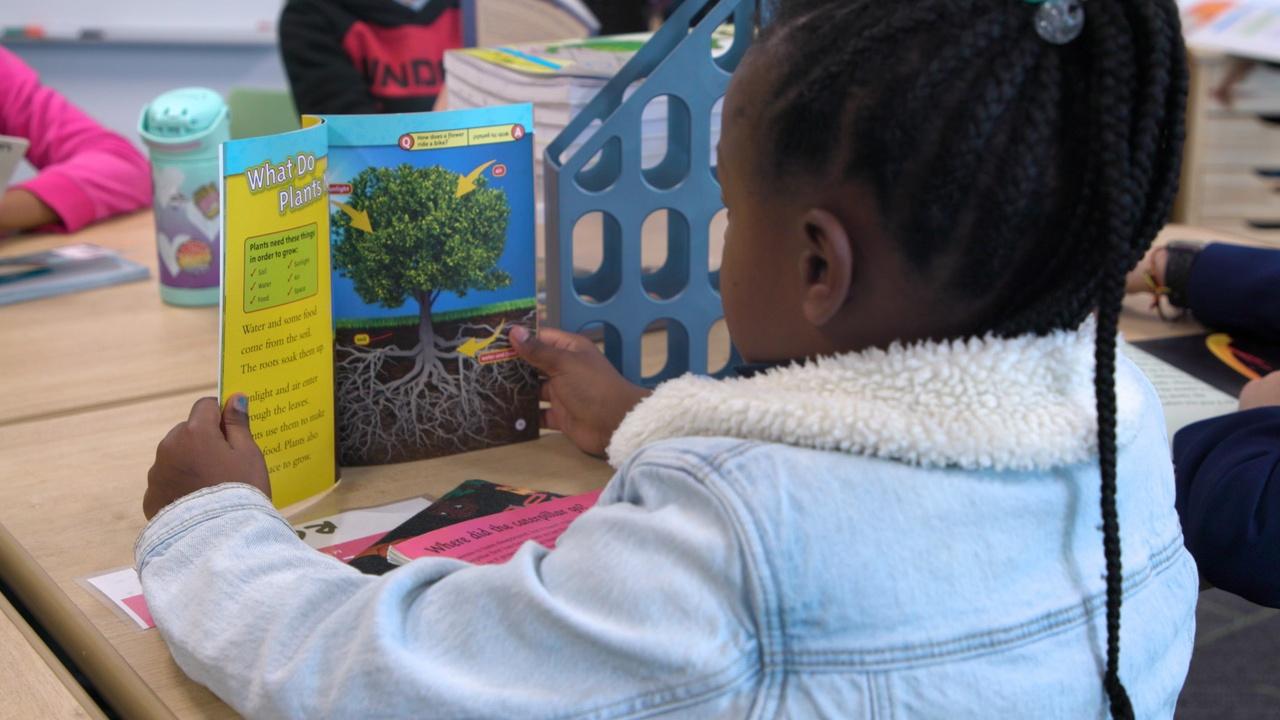

But educators across Wisconsin are working to reverse these trends. At One City grade school in Madison, the focus on reading is key.

Kirsty Blattner:

Yeah! It kind of continues on.

Murv Seymour:

Third grade teacher Kirsty Blattner teaches reading skills at this public charter where more than 80% of the students are Black, Hispanic, or multiracial. Blattner is passionate about making sure her students embrace reading.

Kirsty Blattner:

I have a deep passion for helping scholars that are struggling academically. If you have a scholar that doesn’t feel confident and comfortable with reading, then they’ll find other ways to sort of mask that. Because no one wants to be seen as not knowing. Instead of, “I can’t do this, I can’t do this yet.” Instead of, “I’m not good at this.” “What are you good at? Would you like to be good at this?”

Sara Shaw:

America has trouble talking about race, period.

Murv Seymour:

Sara Shaw researches education for a nonprofit think tank out of Milwaukee, called the Wisconsin Policy Forum.

Sara Shaw:

There’s a trope in literacy circles that before 3rd grade, students are learning how to read. And after 3rd grade, students are reading to be able to learn. Think of how many of your daily activities become more difficult. Everything from reading street signs, to menus, to engaging in the legal system, or going to the doctor’s office.

Dr. Tremayne Clardy:

Education is the conduit to freedom.

Murv Seymour:

From grade school achievement to high school where one superintendent can boast the benefits of a diverse student body.

Dr. Tremayne Clardy:

We’re approximately 35% students of color here in the Verona Area School District. We celebrate diversity here in the Verona Area School District, and we understand that a diverse clientele in the students that we serve allows us to be a better district.

Murv Seymour:

Inside the district’s signature $150 million high school, Verona Area school superintendent Dr. Tremayne Clardy is straightforward about his commitment and obligation to create equity for all students in his district, especially those that are Black and brown.

Dr. Tremayne Clardy:

It is our responsibility to move barriers but never, never lowering expectations.

Murv Seymour:

While recent statewide data shows a gap in the graduation rates of Black and brown students compared to white students, Dr. Clardy and other educators believe the difference in achievement has less to do with performance, and more to do with something else.

Dr. Tremayne Clardy:

It’s opportunity. It’s definitely not skill. It’s not intellect. There’s not any other internal barrier on behalf of our Black and brown students. It is purely about access.

Murv Seymour:

Opportunity and access are why this school has windows in place of walls, and wide open common spaces.

Dr. Tremayne Clardy:

We are modeling, you know, other students seeing that collaborative process. We set up our furniture that way. We set up the classroom structure that day, because you know the power of peer-to-peer interaction, and what that means to strengthening education.

Carri Hale:

What is that thing that’s in you?

Murv Seymour:

Meet guidance counselor Carri Hale.

Carri Hale:

There’s no typical day in the world of a high school counselor.

Murv Seymour:

In the spirit of strengthening education, in 2018, the district sent her, and every other teacher to the Nehemiah Justified Anger “Black History for a New Day” course.

Dr. Tremayne Clardy:

We really had to get to the root and heart of the history of the systems that have caused barriers that we’re trying to dismantle.

Murv Seymour:

For Carri Hale…

Carri Hale:

It just fed me.

Murv Seymour:

…the course has been life changing.

Carri Hale:

It’s just grown in me over the years, and I realized at that time, there was so much I didn’t know. It benefits me as an educator so that when I’m working with a student who doesn’t look like me or their family speaks another language, whatever it might be, that I can respect them and value them, and see them, and honor them for who they are in this space we’re in.

Gerald Montgomery:

Well, I definitely struggled trying to figure out who I was, just like everybody else.

Murv Seymour:

Senior Gerald Montgomery says attending this diverse high school has made him more culturally aware than ever.

Gerald Montgomery:

When I came here, it was kind of like a cultural shock, seeing not too many faces looking like me.

Murv Seymour:

It’s one of the reasons Gerald got involved with the school’s Black student union group…

Gerald Montgomery:

It’s just more of, like, celebrating Black culture.

Murv Seymour:

…which anyone can join.

Gerald Montgomery:

The first BSU year, it was, like, small, like, 10 people, when I was a freshman, and now it’s like 80. And just seeing like that group of Black folks around me, I feel like that really helps keeping, like, that balance of me going through school and everyday life.

Murv Seymour:

Gerald says he plans to go to college. If he goes to a University of Wisconsin school, he’ll be one of a few Black students doing so. Enrollment numbers show that in 1975, just 2.5% of students were Black. Nearly 50 years later, their numbers in 2022, still make up just 2.9% of enrollment law. While Professor Ion Meyn believes the numbers should mirror the demographics of the nation’s Black population of about 14%.

Prof. Ion Meyn:

If that gets to 3%, is that progress? No. We’re not close to progress. We’re not close to even reckoning with our problem.

Murv Seymour:

The UW System lists diversity as a core value, and it’s five-year plan calls for boosting African-American enrollment to 15% by 2028.

Dr. Equan Burrows:

College is a aspiration that is not afforded to all. It’s our honor to serve and be one of the only majority-minority institutions in the state of Wisconsin.

Murv Seymour:

Dr. Equan Burrows is the dean of students at Milwaukee Area Technical College, where more than half the full-time student population are minorities.

Dr. Equan Burrows:

It’s important that we level that playing field. Look forward to being the mentors.

Murv Seymour:

Dr. Burrows runs a mentoring program with about a hundred Black male students called the Men of Color Initiative.

Dr. Equan Burrows:

The goals are to educate and empower students.

Murv Seymour:

The program hopes to give students like Jeremiah Crawford a better chance to finish college and keep pace with other students who eventually gain their bachelor’s degree.

Jeremiah Crawford:

I’ve always wanted to go to college. My home life was a shambles. It was rough having a father on drugs.

Murv Seymour:

If that wasn’t enough.

Jeremiah Crawford:

High school was a point where I started to retreat into myself.

Murv Seymour:

Jeremiah has something else that makes learning and life more difficult.

Jeremiah Crawford:

My sickle cell stood in the way.

Murv Seymour:

He copes with the blood disorder sickle cell anemia.

Jeremiah Crawford:

The last thing that you wanna do is pick up a book, and my illness would just take over. The Men of Color give us an opportunity to meet, and share our emotions and our feelings, and struggles we’re having.

Murv Seymour:

When it comes to reading…

Jeremiah Crawford:

It’s a skill that a lot of people are missing in this day and age.

Murv Seymour:

Jeremiah knows its importance. Every day he says he does…

Jeremiah Crawford:

About an hour to two hours of reading. I would set an alarm for 15 minutes. Read, stop reading, take a break.

Murv Seymour:

He agrees with experts like Dr. Ladson-Billings who say, reading about things you like, organically, leads to more reading.

Jeremiah Crawford:

If you like self-help books, you should look for that. If you want to learn how to work on a car, you should read those type of books.

Classroom teacher:

I think that’s really good; I liked it.

Murv Seymour:

Hitting the books is often new for a population that schools can leave behind. People whose incarceration cut learning short. An innovative program hopes to change that.

Peter Moreno:

There are many, many justifications for higher education in prison.

Classroom teacher:

You opened up a really important conversation.

Murv Seymour:

This college classroom is inside a prison. Odyssey Beyond Bars conducts this college-level English composition course at Racine Correctional and three other prisons across the state, on behalf of the University of Wisconsin.

Peter Moreno:

It transforms how they look at their lives. Virtually all of our students have reported to us at the end of the class, that the experience in Odyssey has made them want to take more college classes. There are people in prison who look around and think, “I don’t ever want to be back here again, “and I want to do something about my life that ensures that I don’t.”

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings:

I gave the, quote commencement speech at Oakwood Correctional Center.

Murv Seymour:

Each time, Dr. Ladson-Billing says, she’d ask one question.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings:

“Raise your hand if you were ever suspended?” I’ve never had less than 100% of the hands go up.

Murv Seymour:

Suspensions and expulsions from high school can lead to what has been called, “the school-to-prison pipeline,” and at the very least, disrupt graduation, and college attainment.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings:

Now the prisons are having to go back and say, “Listen, let’s make sure you get the education you should have gotten.”

Murv Seymour:

If fixing the opportunity gap for Black and brown students is a puzzle, another important piece of it is the shortage of minority teachers.

Kabby Hong:

They talked about how my dad would move out, and how me and my sister…

Dr. Tremayne Clardy:

Our students want and deserve to see someone that looks like them.

Murv Seymour:

For his part, Superintendent Clardy is proud of his efforts in his district to diversify its staff with people like Kabby Hong, Teacher of the Year.

Kabby Hong:

And then, if you look at this paragraph. For so many kids of color, they’ve never had a teacher of color. A lot of the university programs are not diverse. So if your feeder pool of teacher applicants is not diverse, then, of course, you’re not gonna have a diverse teaching workforce.

Murv Seymour:

In 2020, researchers at the Wisconsin Policy Forum took an extensive look into the racial diversity of Wisconsin teachers, and the student-to-teacher pipeline. The takeaway…

Sarah Shaw:

We have a lot more work to do.

Murv Seymour:

Shaw says, ideally…

Sarah Shaw:

That the diversity of the student body would be reflected in the diversity of the teacher population.

Murv Seymour:

While almost a third of students in Wisconsin are students of color, only about 6% of their teachers are, and many don’t stay.

Sarah Shaw:

Teachers of color who come into the workforce are leaving at a faster rate than our white teachers.

Murv Seymour:

Many educators say a diverse teaching staff positively impacts all students in a lot of different ways.

Sarah Shaw:

We see positive impacts across everything from student motivation to strong student-teacher relationships, to absenteeism, graduation rates and going on to college.

Kabby Hong:

When you look at the educational inequities, I think it is just intrinsically tied to the inequities that are in society, but it’s gonna take policy changes– not just talk.

Sarah Shaw:

For his part, Verona Superintendent Clardy is moving beyond talking and taking action.

Dr. Tremayne Clardy:

I’m not a worrier; I’m a doer. And so we’re about doing the work.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us