[solemn music]

[hammering]

Nathan Denzin:

Owning a home has always been key to the American dream.

According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Homeownership is a pillar “of wealth building for most families, a source of wealth that can be passed down to future generations.”

– Having the ability to purchase a home and live where one chooses is, you know, should be a fundamental right.

Nathan:

As African Americans moved to Wisconsin in large numbers after World War II, they entered a segregated housing market.

– When we think about racism, when we think about Jim Crow, we have a tendency to focus on the South, when it was universal throughout the United States.

Nathan:

Including here in Wisconsin, where starting around 1900, racism was built into home ownership.

– Racially restrictive covenants were clauses that were inserted into property deeds that prevented people who were not white from owning, buying, or occupying property.

Nathan:

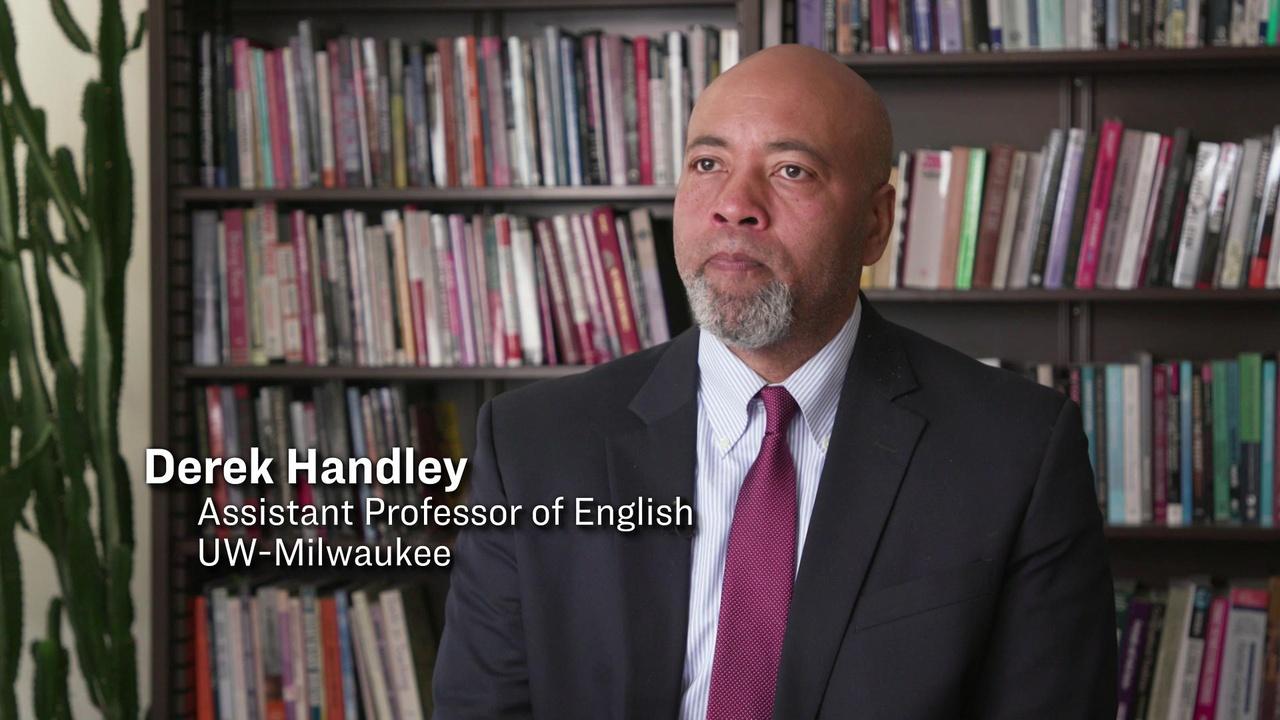

Anne Bonds and Derek Handley are professors at UW-Milwaukee, where they map old covenants in the city of Milwaukee and its surrounding suburbs.

– By 1928, about half of all homes that were owned by white people in the United States had some sort of a restrictive, racially restrictive covenant.

Nathan:

Often, restrictive covenants had sweeping language.

Derek Handley reads this one from Wauwatosa.

– Number eight, “Ownership and occupancy “by members of white race only.

“No lot in said subdivision shall be conveyed or leased to “or occupied by any person who is not a member “of the white race.

“This prohibition is not intended “to include domestic servants while employed by an owner or occupant of any such lot.”

So now African Americans have limited areas in which they can live, in which they can spread.

And so now they’re gonna be crowded into one area.

– Black people who come during the Great Migration are already coming to a space that has a history of anti-Blackness, that has a history of racism.

These are the people who are shaping the texture of your life.

Nathan:

Dr. Clark-Pujara, a UW-Madison history professor, also works with the Madison organization Nehemiah.

She’s an instructor in its “Justified Anger: Black History for A New Day” course.

The nine-week course teaches the community about race, history, and justice.

– Housing is critical because this idea of being able to pay the same amount, month after month, for 30 years with little to no money down transformed American life.

Nathan:

While restrictive covenants were made unenforceable by a 1948 Supreme Court ruling, they continued to be added to property deeds.

– After 1948, we have examples of deeds in the 1950s, and the latest one we found so far is 1962.

Nathan:

Even though covenants fell out of use in the ’60s, other long-standing tools of racial segregation, like redlining, continued to carve up neighborhoods.

– The term redlining comes from a set of maps that were drawn by the federal government.

Nathan:

Reggie Jackson educates people about diversity.

He says that the redlining maps weren’t common knowledge.

– They were, for the most part, secretive maps.

Nobody really knew they existed other than bankers and some realtors.

– And so the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation in 1933 and the Federal Housing Administration in 1934 adopted a mechanism where they drew lines on a map.

Nathan:

UW-Madison professor Kurt Paulsen is a historian of urban planning.

– What redlining said was who could get a mortgage refinanced.

Nathan:

Redlining maps, like this one drawn for Milwaukee in 1938, divided cities into four grades.

Green areas were considered the best place for banks to invest in, while red areas were deemed hazardous and not worthy of additional investment.

– One of the criteria that the FHA and the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation used was the presence of what they call, quote, “inharmonious racial groups.”

– Neighborhoods where Black people live were always redlined, and so what that meant was it was exceptionally difficult to become a person who could get a traditional bank mortgage to purchase a home or a business property.

– What that meant was that a Black person, if they moved into a yellow or a blue zone, would change that neighborhood to a red zone, and all of a sudden, that white person’s property would be, would lose huge value.

Nathan:

UW Law School professor Ion Meyn says the patterns of segregation we see today stem from these policies.

– So a Black person became a threat to white wealth and it created hyper segregation.

– And it not only created disinvestment in older urban neighborhoods, it facilitated suburban development.

Nathan:

Because redlining maps sent government subsidies to the suburbs, urban communities were left with old housing and high prices.

– In many cases, Black people in deteriorating and urban neighborhoods were paying more in rent than white families were paying in the suburbs.

– That means that Blacks have been left out of the ability to build generational wealth.

[chiming music]

– And what you have is basically a system of state-sanctioned apartheid.

– And I remember as a kid, you know, hanging out here, riding my bike around Milwaukee, and I never saw white people because everybody in the neighborhood was Black.

I didn’t really understand it when I was a kid.

I just, you know, it’s just the way it is.

Nathan:

Reggie Jackson has lived in Milwaukee for most of his life and takes people on segregation tours of the city.

We joined him to see the lines of segregation up close.

– One of the best ways to see the segregation of Milwaukee is to visibly just drive along one of our main streets, North Avenue.

Nathan:

He says the Milwaukee River is one of the largest invisible borders.

– Once you cross from the west to the east across the river, you know that you’re not gonna see a residential area that has anything other than white people in it, for the most part.

Developers not trying to build homes in this part of town.

It’s a really, really a sad situation to me.

Nathan:

Jackson says that in order to restore Black neighborhoods in Milwaukee, investments in jobs and affordable homes are a must.

Reggie:

Clearly missing is the fact that people can’t afford to become homeowners.

People aren’t making enough money.

Nathan:

But Jackson says that in order to capture investment for the future, we have to look at how we got here.

– Ours is a complicated history, and we can’t hide from it.

We have to understand it; think we have to learn from it, and we have to grow from it.

[blues music]

Milwaukee Resident:

People here are suffering now.

What do you wanna do about it now?

What are you gonna do about it now?

How many homes do you have available now for us?

Nathan Denzin:

Bulldozers rolled into Milwaukee in the 1960s, leveling Black neighborhoods in the name of urban renewal.

[bulldozers roaring]

The projects often razed successful Black neighborhoods like Bronzeville in downtown Milwaukee.

– Well, you had homes with families and with kids, and we were all just playing around.

Nathan:

Theresa Garrison has lived in the Bronzeville community for 70 years.

Theresa:

So I’d say it was family-oriented and everybody knew everybody.

Nathan:

Bronzeville enjoyed a flourishing business district in the early 1960s, from banks to movie theaters to grocery stores.

Theresa:

It was just a booming shopping center.

Nathan:

But in the mid 1960s, the federal government started giving grants for cities to update infrastructure.

The goal of urban renewal was to construct new housing and modern interstates.

Those projects often destroyed Black neighborhoods in the process.

Narrator:

Fred Durra and his family have lived in this house for eight years, but they live in the K3 urban renewal area and they have to move now.

There are 13 of them, and they are Black and poor, so they won’t be able to find a decent home on their own.

– As far as urban renewal, I’ll just say it was urban tragedies.

Nathan:

In just eight years between 1960 and 1968, more than 7,500 homes and businesses were demolished in Milwaukee.

Interstate 43 was the largest and most visible urban renewal project in Milwaukee and was built directly through Bronzeville.

– The addition of I-43 decimated the neighborhood.

– Friendships that were very close to having a family connection were disrupted and destroyed, and a lot of families never recovered.

Nathan:

Elmer Moore, Jr. and Ranell Washington play critical roles in the Wisconsin Housing and Economic Development Authority.

– What does that do to everyone else’s sense of security?

I wouldn’t be able to sleep that night, thinking, “What are they gonna do to my home next?”

Ranell:

Everybody deserves to have a house.

Theresa:

When they start tearing a community apart, there was nothing to do.

You didn’t have anything.

Nathan:

The Black community was now facing three forms of discrimination at once.

Restrictive covenants prohibited them from living in certain areas, redlining prevented them from getting mortgages, and urban renewal destroyed their neighborhoods.

– Black households that were displaced by highways and urban renewal had limited housing options in the city because of discrimination and exclusionary zoning in the suburbs.

Nathan:

Kurt Paulsen is a historian of urban planning at UW-Madison, who says decades of discrimination built to massive protest.

– No surprise that you get significant political pushback and rebellion amongst African Americans in disinvested neighborhoods.

– We tend to think about the civil rights movement, like the institution of slavery, as something that is uniquely southern, and it was not.

Nathan:

Dr. Clark-Pujara, a UW-Madison history professor, also works with the Madison organization Nehemiah.

She’s an instructor in its “Justified Anger: Black History for a New Day” course.

The nine-week course teaches the community about race, history, and justice.

– You can just look at the civil rights struggle for open housing, for instance, in Milwaukee.

Nathan:

The pushback in Milwaukee started in the 1960s when Vel Phillips was elected to the city council.

Phillips was both the first woman and the first Black person elected to a city office.

She led the charge to desegregate Milwaukee’s housing.

– These cats are just too dumb, just too dumb to know when they have something going for ’em.

It’s bad enough… – Kurt: And they argued in favor of reinvestment in Black neighborhoods, but also what we today would call fair housing or open housing.

Nathan:

Fair housing is the idea that discrimination of any kind in the sale or rental of housing should be prohibited.

When Phillips first introduced her fair housing ordinance in 1962, the rest of the council overwhelmingly rejected it.

– It was one of the first proposed in the country and it went down to defeat 18 to 1.

Only Vel Phillips voted for it.

– Y’all have done this #### for over 200 years, telling us what felt good for us.

Nathan:

Over the next four years, the ordinance was shot down four more times, each time by the 18 to 1 margin.

By the summer of 1967, Milwaukee reached its boiling point.

A group of young Black activists decided to rally their community around a common goal.

Their mindset: – We are going to march and demand that the local government, the city of Milwaukee, passes a fair housing ordinance that has some teeth to it.

Nathan:

Reggie Jackson is a community leader in Milwaukee.

Reggie:

So they marched for 200 consecutive days.

The first two days they marched, they were met crossing this bridge in Milwaukee called the 16th Street Viaduct, which separates the north side from the south side.

They were met by an angry crowd of thousands of white people, throwing bricks and bottles and bags of feces.

Nathan:

Despite the angry white crowds, protestors kept up the pressure.

– Anybody that knows anything about the weather in Milwaukee, marching in December, January, February when it’s bitterly cold, snow, blizzards, all that stuff, ice storms, they continued to march.

Nathan:

Protests continued until March 1968.

Less than a month later, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis.

As unrest grew after the murder of Dr. King, the federal government felt pressure to pass an open housing law.

– The federal government finally passed the Federal Fair Housing Act a week after Dr. King’s assassination.

– But that’s after 40 years of segregation.

And a law prohibiting discrimination does not address the deep structure of segregation that was already built into the urban landscape.

Nathan:

As an expert on the deep and lasting scars of discrimination and forced segregation, Clark-Pujara says understanding that past is critical to working towards a better future.

– So now we’re in a situation where things are very lopsided, but we can address them as a society if we choose to.

[contemplative piano music]

Nathan Denzin:

Historical wrongs like blatant housing discrimination in Wisconsin.

– I am sorry.

We don’t feel that we can rent to colored people.

Nathan:

The Federal Fair Housing Act is supposed to protect renters or buyers from discrimination based on a number of protected classes, including race.

[dog barking]

However, discrimination in the housing market has persisted in the 55 years since it became law.

Tester 1:

Is as or more prevalent today than it has been in the past.

Tester 2:

The discrimination is a reality.

It’s not hypothetical, it’s not theoretical.

It still happens; it’s just more subtle.

Nathan:

These two people, one white and one Black, test for discrimination in housing as a part of Wisconsin’s Fair Housing Council, a nonprofit that ensures realtors and landlords follow the law.

They have been made anonymous to ensure they can continue to test.

– Well, I’m not gonna rent it to you.

– I’m sorry?

– I’m not gonna rent it to you.

Nathan:

This 1961 film was recorded in Madison at the height of segregation, but it was hidden by the University of Wisconsin and never shown to the public until 2021.

Flash forward to today.

Tester 2:

In today’s time, it’s probably more subtle, but they’ve already concluded that they’re not gonna rent you the apartment.

Nathan:

The two testers from the Fair Housing Council recently toured the same apartment building and found discrimination based on race.

Tester 2:

I went to an apartment building.

I asked if a unit was available October.

They said nothing was available.

Tester 1:

Yeah, they did show me more than one apartment, so they were very, very eager to show me around.

Nathan:

However, the Black tester had a different experience.

Tester 2:

But I never saw the actual unit because it wasn’t available.

Tester 1:

One thing I remember clearly about this is that they were just so engaging and they repeated, like, two or three times over, you know, the amenities that they had.

Tester 2:

Then the person made a slip-up and said, “Well, there was something available in October, but that’s gone now.”

And so then you become aware of, like, what’s going on in the back of your mind.

Nathan:

On top of discrimination by landlords, lenders like Associated Bank in Milwaukee, Racine, and Kenosha were part of a recent $200 million redlining settlement.

A federal complaint in the case alleged the denial of mortgages to Black and Hispanic applicants.

– Many banks have been caught with their hands in the cookie jar, giving Black and Latino borrowers different loans than they give whites.

Nathan:

Reggie Jackson educates people about diversity.

Jackson noted that despite the Fair Housing Act, the Black home ownership rate has not improved much since 1968.

Ranell Washington says that shuts Black families out of the ability to create generational wealth.

– Housing is the cornerstone to the beginning of a financial journey.

– There have been laws and policies that created some of the disinvestment, the plight, and the wrong that we’re experiencing today.

Even if those laws were changed 50 years ago, the consequences of them are still absolutely present.

Nathan:

Elmer Moore, Jr. and Ranell Washington play critical roles in the Wisconsin Housing and Economic Development Authority.

– It’s about trying our best, honestly, to correct some historical wrongs.

Nathan:

The duo cares deeply about evening historical gaps caused by housing discrimination.

They provide affordable loans, rental units, and mortgages to low-income individuals.

Plus, they invest in future housing or business projects.

– There’s 147,000 families who’ve been able to buy homes across the state because of the mortgages WHEDA made available, and they might not have otherwise been able to afford those things.

– Making really intentional decisions to spur affordable housing development in our inner city communities is one of the ones that we definitely have a lens on.

– That’s sequestering some resources and intentionally investing in Black communities.

It’s the right thing to do.

Nathan:

WHEDA has funded developments in Milwaukee’s Bronzeville neighborhood, including The Griot, which fashioned apartments out of an old schoolhouse.

Elmer:

It brought new businesses.

It obviously brought new residents.

It also does things like plants new trees.

– Housing is that cornerstone, and from that, I can have conversations about aspiring to be a entrepreneur.

Nathan:

Building equity in your house can spur the creation of a second way to build wealth: your own business.

And while Black-owned businesses have seen an uptick in recent years, there is still a large disparity between Black and white-owned businesses in Wisconsin.

– And our work does what lots of folks don’t do, primarily, is to center the needs of Black women.

Nathan:

Sabrina Madison is the founder of the non-profit Progress Center for Black Women in Madison.

– The first level that I really wanna see is Black folks having more power in their pockets.

And I always go with the fact Black women in Dane County on average in 2016 earned 57 cents on every dollar made by white men.

I wanted to give Black women another option to be successful.

Nathan:

To help close the gap, the Progress Center provides Black women with programming that includes financial health, professional development, and entrepreneurship.

– Oftentimes, programming is very piecemeal, where you gotta go to one side of town for this, you gotta go somewhere for that, you gotta wait on a phone call for this other thing.

And we wanted to sort of, like, center all of your needs in one space.

Nathan:

Madison says her foundation has helped hundreds of women create their own business or secure a better job.

– I absolutely wanna see the rest of the state, but more importantly, Madison and Milwaukee extend its Black leaders through wealth creation because with wealth, you have more power.

Nathan:

Despite the work of WHEDA and the Progress Center, Madison says everyone has to buy in to make Wisconsin a more equitable place.

– So these visions that Black folks have for their lives as Wisconsinites, ’cause we too are from Wisconsin and we too live here, that you want to also be part of this vision and see this vision expanded.

Nathan:

While that vision might take years to be realized, Madison says the work starts today.

For Here & Now, I’m Nathan Denzin.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us