The School-To-Prison Pipeline

"We can create healing environments, where education is anchored into the reality of what we're grappling with."—Rudy Bankston

GUEST

Roderick 'Rudy' Bankston

Roderick “Rudy” Bankston is a committed educator, entrepreneur and writer. Rudy is a survivor of the school-to-prison pipeline. He was wrongfully convicted and sentenced to life in prison at 19 years old and spent 20 years in prison before winning back his freedom on an appeal in 2015. In May of 2020, he completed his parole. Rudy’s published works include Buried Alive: Poetry Born of a Life Sentence and Snippets of Soul in Seventeen Syllables.

TRANSCRIPT

Angela Fitzgerald: According to the Madison School District, 57% of school suspensions in 2019 were given to Black students. Why is that? Large education gaps, poverty levels, and zero-tolerance policies are huge issues that affect Black education in Wisconsin. Today, we’ll talk to one survivor of the school-to-prison pipeline and how they’re using their story to help Black youth in Wisconsin. But first, let’s explore why race matters when we talk about education.

[upbeat music]

The Landmark 1954 Brown vs Board of Education Supreme Court case declared that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. Even then, it wasn’t until 1976 that federal judge John Reynolds issued a court order to desegregate Milwaukee’s Public Schools. However, Black students are still segregated by school policies. The 1990s saw ineffective zero-tolerance policies that led to the hyper criminalization of Black students. Yet, school districts still pushed for extra precautions. In 2007, Milwaukee Public Schools brought police officers known as school resource officers or SROs to their district, which led to an increase in school arrests and citations. In Madison Metropolitan School District, Black students made up 81% of citations and 64% of arrests made by police between 2019 and 2020. Organizers and activists like Rudy Bankston work tirelessly to address the criminalization of Black students and the pipeline between schools and the criminal justice system. Well, thank you for joining us today, Rudy.

Rudy Bankston: Thank you for reaching out and inviting me.

Angela Fitzgerald: Of course, you have a lot to share on this topic. So, to get us started, though, can you tell us your story and how it has landed you in the field and area of work that you’re in?

Rudy Bankston: I grew up in Milwaukee, the youngest of four. Grew up on the north side of Milwaukee and this is the ’80s and ’90s and attended public education. A lot of bussing was happening back then, so…

Angela Fitzgerald: Does that mean students being bussed to other schools outside their neighborhood?

Rudy Bankston: Yeah, predominantly white communities. And there’s a wooded area. So it was the school, it was a parking lot. And it was like two, three blocks of wooded area where folks would go, students would go hang out. We would sneak out during lunch and just kick it a little bit. Some– sometimes skip, sometimes just hang out after school in there. ‘Cause it was just place where folks went– students went and hung out. And one day, there was a group of us in that wooded area with a fake gun. And it was not the serious looking fake guns today.

[chuckles]

It was like a real fake gun. The next day, I think it was, I’m sitting in the classroom and a security guard come get me in the classroom, pull me out, and say, “Hey.” Started talking to me about a gun, and I don’t know what the hell he’s talking about. ‘Cause his tone was like a real gun. I’m not even drawing a connection to when we were kicking it in the woods. I’m not drawing any connections. So, I didn’t realize what they were talking about till I got into the principal’s office, and two police officers are in there and they throw me in handcuffs. Tell me the details. I say, “Listen, that’s a fake gun.” I told them where it was at; it was at home. I told them where it was at. They put me in handcuffs and took me away and locked me up in the detention center. They expelled me from the school.

Angela Fitzgerald: Wait… wait, wait! So, this is over allegations around a toy gun that was in the woods at your school…

Rudy Bankston: Yeah, a fake gun…

Angela Fitzgerald: …that you were arrested and expelled?

Rudy Bankston: Expelled immediately. No, you know… I was expelled and I was placed in an alternative. I spent maybe two, three days in a detention center. And this alternative school where– Alternative schools in Milwaukee at that time, you had some folks who were really trying but they were under-resourced and they were seeing some of the worst teachers and maybe not worst but teachers with the poorest records. That that became my new peer group and it spilled over. We kicked it. We started hanging out in this, but this became my new peer group. Meanwhile, my mother working full time. But by the time I was 18 years old, I was arrested for first-degree intentional homicide party to the crime, first-degree reckless endangering the safety party to the crime. This was during the OJ trial when I was going to trial. And I was just really understanding a lot more about race and what not. But I had two trials. First trial ended in a mistrial. Second trial, I had an all-white jury and it was, and again, this was at– This was at the height of the OJ Simpson trial, and the racial divide that was being exposed– not new, but exposed. And I recall one of the jurors, she was tryna– she was tryna exclude herself from doing it and the judge asked why. She said, I was on a highway one day and I cut off this group of Black guys, and I cut ’em off. And I think she said, she gave them the finger and they caught up with her and, like, threw a soda out the window and it splattered all– She’s like graphic and all the people in the jury pool they’re like looking all sad and like sympathizing. And then, she was like, and they never got caught. And it felt like in that moment they looked– The energy was like, this one won’t get away though. You know what I mean? So. I’m there paranoid.

Angela Fitzgerald: “But I wasn’t in the car.”

Rudy Bankston: This is… you know. So meanwhile, I get found guilty. And I always say, I’m not innocent in terms of, like, I fell off into the streets. You talking about the ’90s in Milwaukee. Like, you know what I mean? But I was not guilty of this particular case. While in prison, I began to educate myself. My cell truly became a classroom.

Mm-hmm. I ordered books and I can say it now– We can only have a limit on books in prison. So I started building libraries in other guys’ cell that didn’t read and just have my people send them books.

Angela Fitzgerald: Wait, what was the maximum of books?

Rudy Bankston: Twenty-five publications. Through that reading, I started to really discover how resilient and beautiful and how much genius Black people hold. And growing up, in education always got the slave story.

Angela Fitzgerald: Right.

Rudy Bankston: But even with that slave story, I got us as victims. And knowledge became… Like, it became innate, like this is a part of who we are, you know what I mean? And this is stuff I never learned. And again, even when we got to slavery, the story was different. Like how much genius and resilience it took to survive, even in some instances thrive when the world was set up to crush you and make you feel less than. I learned about why we went from Africans to Negroes. And when you rob people or their names then you can define who they are. And so, it was just so much stuff that I was learning during that time. And I began to really– truly realize that our ignorance is weaponized against us. It helps you to… to have this intimate relationship with your humanity. And when you know, you’re a human you’re not finna accept slavery or oppression. And it’s similar to today. When we know what we’re truly worth, we’re not gonna accept. So just that education piece became critical but not a white-centered education.

Angela Fitzgerald: I was gonna say ’cause when people hear the word education, a certain idea comes to mind, the assumption is like, well, we have education, but as you’ve already pointed out, like, what type of education, what sort of messaging is that education communicating to Black students? And if it’s reinforcing this negative narrative then how is that going to make that student feel empowered in your classroom? Right? Like, stereotype threat is a thing. It’s an absolute thing, right? How is that causing me to view myself in a way that is empowering, that I can then perform well? Or is it feeding these defeatist victim mentalities to me so I don’t even think that I can? And I’m so hard trying to disprove this idea that I can’t, that I’m underperforming. Right? Yeah, overhauling education and just confronting how we go about it. Like, absolutely. Like, who is it serving? And if it’s not equally serving everyone then what needs to change?

Rudy Bankston: Like, the prison system is a cemetery of some of the best talent in the world, just sitting there. And a lot of these men would rediscover writing, and music, and philosophy, and just deep, deep stuff.

Angela Fitzgerald: Well, let me ask you this because– And thank you.

Rudy Bankston: Yeah, yeah.

Angela Fitzgerald: Your story, I feel like you could get a movie, docuseries, something.

Rudy Bankston: Make it happen, let’s get it.

Angela Fitzgerald: I mean, we are a media company. I was like, I can do that. Wait a minute.

Rudy Bankston: Yes, you can.

Angela Fitzgerald: We can talk about that. No doubt. But I’m thinking about like, those who are listening to this and are thinking, okay, we started off talking about like his time in school. And then we talked about your time within the criminal justice system. I want to elevate why it’s so important to talk about those two systems being connected.

Rudy Bankston: Because they– one feeds the other. My school-to-prison pipeline started in middle school when they said, “Get out.” That changed the trajectory of my life. When I got kicked out of that middle school and went to that alternative school, the streets became a part of who– like, they said, “Get out,” and you know what I mean? So, that story started in middle school as it often does with young people. Part of the work that I do also, not only where I mainly work with adults and work with adults around race and racism and things and it can be anything from curriculum development to building just and equitable learning environment but I also contract with a part of one of my contracts is working with these young people in the juvenile system right here, downtown in JRC. And I’m seeing the same thing in terms of like smart, gifted, in unique ways that don’t fit the mold of, but like– And you just want to like, how do we pull these resources and get them what they need? Our young people spend more time in these schools.

Angela Fitzgerald: Yes.

Rudy Bankston: And their reality of themselves and the world is getting shaped. And education is like it’s always been. It’s like a serious hit or miss. You don’t show up with all the answers. You show up, you listen to the people, they give you all their thoughts, their wisdom jumbled all up and your job as the revolutionary is to go and organize that knowledge and wisdom and give it back to the people. And I think that’s the same relationship that has to be done with young people where you have to show up expecting them to teach you some things. ‘Cause they’re gonna teach us like a parent and a child. That child is gonna teach you how to be a father. You don’t have to have all the answers. You just need to pay attention to what– Yeah, yeah. And it’s the same with education. But it’s really difficult because if you’re an educator, and you’re showing up with all this bias that society has. When you think about white supremacy culture, it’s the air we breathe, the water we swim in. So, we’ve all internalized that, but you show up in a classroom and you’ve not done any of your own identity work, and you’re showing up with this. And then, the district is constantly pounding data in your head about how Black kids cannot learn. And then they say go in the class and change and teach Black kids. So you have to have some very deep and intentional unpacking.

Angela Fitzgerald: I feel like sometimes it’s not even data that specifically says that, but it’s the comparisons, right? So, if you’re saying, oh, that Black students are performing in this way, by comparison to white students, that’s setting up white students as the norm by which everyone else is then expected to level up with.

Rudy Bankston: That’s the very epitome of white supremacy. Because if you’re the norm, you’re the superior.

Angela Fitzgerald: Right.

Rudy Bankston: You know what I mean? And if you’re not learning in that dominant way, if you’re not fitting into that cookie cutter approach to education, then that’s how so many people end up in prison with such deep intelligence. But they may learn in unique ways. Again, people of color, specifically speaking for myself as a black person, we internalize this stuff as well. So we have to continue to do our own work. The struggle is we’re expected to do the work of teaching white folks…

Angela Fitzgerald: Right.

Rudy Bankston: …and then also doing our own healing. You know what I mean?

Angela Fitzgerald: And that’s been a consistent theme in all these conversations that I’ve had to date is that there are folks like you who are in the field doing the work, but that doesn’t absolve you from needing to manage your own stuff. I mean, you’ve had like a super traumatic experience for decades. You’re still having to deal with aspects of what that still means for you on top of how you’re pouring into other people and trying to fix this corrupt system or systems.

Rudy Bankston: Yeah, yeah. And the daily chipping away of micro-traumas. I mean, I had to create space for myself because I was carrying a story of institutionalization. And for me, it freaked me out to start seeing the same fear that I saw in the prison system, amongst the staff who wanted to treat quote unquote inmates more humane and how they would be scrutinized. And I show up in education– I did not get that level of fear. And it really shocked me and not from a place of judgment but from a place of, like, how is this living? But that is capitalistic white supremacy culture where it thrives off of keeping people in place. Education is more about compliance than really helping students to become critical thinkers. And when you’re focused on compliance that stuff, it trickles down. So the principal is compliant with the school district. The school district is compliant with the board and then the teacher’s feeling like they don’t have power. So, their classroom becomes the only place of power. So then now they have to get compliant. And that energy around that, it makes it extremely difficult to have those just and equitable learning environments. How can we make sure the well- being of everyone is centered? And how do we make that a part of the curriculum? Like, how do we turn that into lessons? Because one thing that George Floyd and all this other stuff that’s happening, that’s all curriculum and it’s what’s impact. It’s what we carryin’.

Angela Fitzgerald: Right.

Rudy Bankston: So we can create healing environments, where education is anchored into the reality of what we’re grappling with. But it’s also led with hard work. It’s still that headiness head and it’s– Folks are burnt out.

Angela Fitzgerald: I love everything that you just said and especially the emphasis on how we can re-imagine. ‘Cause since we’ve gone virtual there’s been little catch phrases about what’s the re-imagining of education and what’s it gonna look like that’s different and you’re right. But it’s catchphrasey to say that. It’s easier to default to what’s familiar. I feel like some folks are trying to transition but that’s hard to do when the system is structured in a very specific way that this is how education works. But I am seeing more conversations about, how are we centering social-emotional needs? and social and emotional learning such that we’re not ignoring the realities of our students and our families and our staff in this point in history on top of, like, we gotta figure out online learning. Oh, yeah, and it’s COVID. Oh, yeah, and all the other things, right? We can’t ignore that human side of people which you’ve already too talked about. So if we keep ignoring that cell, then that’s not going to serve. Those who we’re trying.

Rudy Bankston: And cell for not only students, but adults.

Angela Fitzgerald: Right.

Rudy Bankston: It’s for a community, but the threat to radically re-imagining anything is how the human, the conditioning around going back to what you’re familiar with. People will prefer a familiar slavery than an unfamiliar freedom because it’s what they’re–

Angela Fitzgerald: They know.

Rudy Bankston: You know what I mean? Even though it’s dysfunctional as hell.

Angela Fitzgerald: There’s comfort in that dysfunction ’cause at least I know what it is.

Rudy Bankston: Yeah, yeah. And that is the biggest threat. But that’s the biggest threat to any real fundamental revolutionary change is you have to conquer that inclination to go to what you’re familiar with, especially when what’s familiar is not benefitting the whole community.

Angela Fitzgerald: So again, you’ve highlighted the issues around school-to-prison pipeline. You gave your own personal story of how that started off. And I hope people understood that entry point and what that looked like and how it just escalated over time. And then kind of how that culminated for you. One of the things I did wanna elevate because you’ve mentioned men quite a few times is the plight for Black girls in particular. And there are books pushed out that are tryna call attention to, “Hey, there’s this issue.” But again, it’s not being spoken about. So, is this something you can speak to briefly before we close?

Rudy Bankston: Thank you for elevating that. It’s just– it’s still that old belief that it’s just a threat to Black males. But I’m in education. Black girls are being criminalized. It’s an adultification of Black girls. You can have– I’ve witnessed it. You can have a group of white female students running down the hall and it’s symbolic and people wouldn’t bat a eye. But you have a group of Black girls running down the hall, and it’s just, you know, ring the alarm. And that’s symbolic. It’s a small thing, but it’s symbolic. But we have got– I worked with our young sisters, particularly, I just– We just had– Our last– They’re quarantining in JRC and our last two students were Black girls. Struggling, like, wanting to do good, wanting to do great things. But society is mean on our Black girls and they are being made to feel that they are not smart enough. They’re not pretty enough. And some of it happens within the family. Some of it happens through media. Some of it happens through school but they internalize that. And there’s a phenomenon in education where Black girls are fighting and they don’t understand where it’s coming from. But what you internalize, you externalize particularly on those who, if you’ve been made to feel you’re not pretty enough, you’re not smart enough. And you begin to develop some stuff and I’m not talking about all because some of our little sisters is just like– they get it, they get it. But there are some of our little sisters, they’re suffering in deep ways. And instead of folks asking, what happened, they’re asking, what’s wrong with you.

Angela Fitzgerald: Exactly.

Rudy Bankston: You know what I mean.

Angela Fitzgerald: It’s– that’s lack of recognition around how trauma, however that’s manifested maybe contributing to what you’re seeing in the classroom.

Rudy Bankston: Yeah, it definitely is.

Angela Fitzgerald: And how that’s been leading to other sorts of issues in school, which could then land you in the juvenile justice system. And that could just accelerate from there.

Rudy Bankston: And then, to be treated, as a young person, to be treated as an adult. Or like, treat young people like whole human beings, but give them space to develop. When you’re made to– when people treat you as if what is happening in your life, you deserve it, you begin to believe that, and then that just creates this spiral. But thank you for lifting that up and checking my patriarchy in the process because it is.

[Angela laughs]

It is, and I need that, I need that. But I– and it’s not like I’m blind to it because I see it. I’ve checked other people about it. When they say our Black boys, our Black boys… No, our Black girls are suffering now. And it’s about creating healing spaces for them. And allowing them, excuse me, allowing them to co-create these spaces.

Angela Fitzgerald: Like you said before, not coming in with the solutions and the hero cape on, but saying, ‘what do you need?’ and ‘what would you like to create?’ that then provides what is it you need.

Rudy Bankston: Yeah, for sure.

Angela Fitzgerald: Wow. Well, thank you for speaking to that. Definitely didn’t want that piece to go unnoticed.

Rudy Bankston: I needed that.

Angela Fitzgerald: I know. It’s this weird kind of juxtaposition of an invisible hypervisibility that I think Black women and Black girls in our state and in our city, like, deal with on a regular basis. And constantly confronting that I think is what we want to take place here. So I feel like you’ve dropped so many nuggets just during our entire time together. So I don’t want you to feel you have to say something that’s like a closeout but if there’s anything that you want people watching this to take away from, whether they can relate to your story or not, whether they’re like, this is new information for me. I wanna help. Or, I’ve been in this and I’m trying to move the needle and I’m just struggling. What do you want them to– what do you want them to connect with the most?

Rudy Bankston: For me, anti-racism work is about tearing down the barriers that gets in the way of us seeing one another humanity. And that work is critical during this time whether you are a 80-year-old or you eight years old. I think our mission is a onion mission where you’re gonna peel, you’re gonna peel. You’re gonna peel, and you’re gonna keep peeling. ‘Cause it’s gonna be lifelong work, regardless of what your race, or your sexuality, or gender is. And sometimes that onion is gonna make you cry. It’s gonna make you cry because right when you think you got it, and it’s another thing shows up and I’m speaking from experience, you know.

Angela Fitzgerald: That is so true. This work is not a checklist.

Rudy Bankston: Mm-mmm. It’s not checkbox work. Like you said, it’s lifelong continuous commitment.

Angela Fitzgerald: Mm-hmm. Thank you for that, Rudy.

Rudy Bankston: For sure.

Angela Fitzgerald: Public education is just that, education for the public. The school-to-prison pipeline and other disparities within the education system can have huge negative effects on people of color, especially within the Black community. A lack of representation in classrooms, administrations and on school boards is also an issue. One of the list of problems that need solutions. To hear more of Rudy’s incredible journey, including how he won his freedom from incarceration, subscribe and listen to our podcast at pbswisconsin dot org slash whyracematters. There, you can also find links and resources to help keep you informed, as well as additional episodes of Why Race Matters.

[instrumental music]

§

Speaker: Funding for Why Race Matters is provided by CUNA Mutual Group, Park Bank, Alliant Energy, Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Focus Fund for Wisconsin Programming, and Friends of PBS Wisconsin.

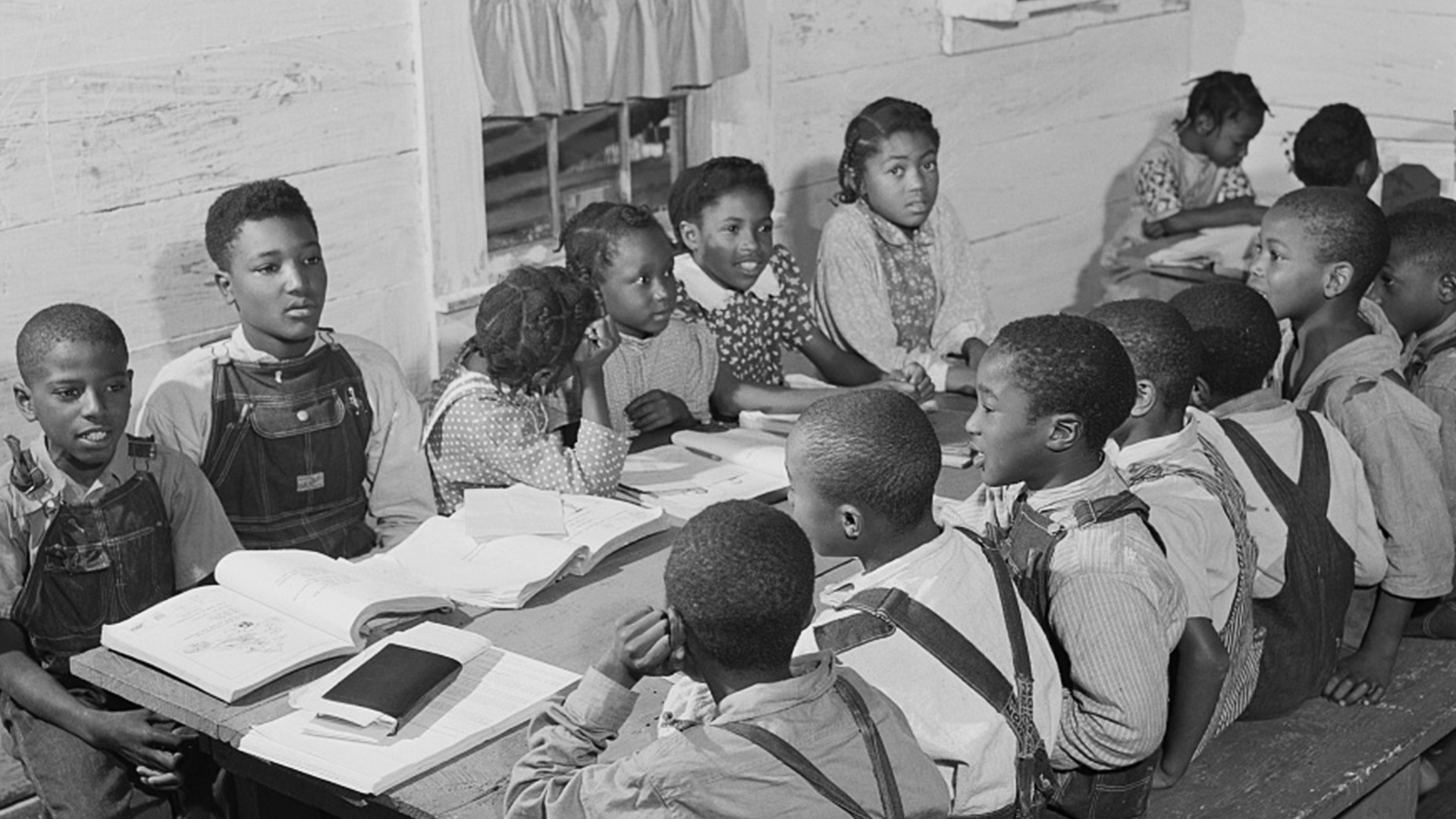

Photo/Jack Delano

Resources

Information on youth mentorship opportunities throughout Wisconsin, learning resources, trauma informed care and further readings on the School-To-Prison pipeline.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us