The School-To-Prison Pipeline

"We can create healing environments, where education is anchored into the reality of what we're grappling with."—Rudy Bankston

The School-To-Prison Pipeline

Wisconsin has one of the widest achievement gaps in the country. In this episode, Angela Fitzgerald talks to Rudy Bankston, a survivor of the school-to-prison pipeline. Rudy shares his story of being wrongly convicted and sentenced to life in prison at the age of 19. They’ll also discuss intersecting themes of identity, as well as how education gaps and strict disciplinary policies in schools can lead to the suspension, expulsion and incarceration of Black students.

Subscribe:

GUEST

Roderick 'Rudy' Bankston

Roderick “Rudy” Bankston is a committed educator, entrepreneur and writer. Rudy is a survivor of the school-to-prison pipeline. He was wrongfully convicted and sentenced to life in prison at 19 years old and spent 20 years in prison before winning back his freedom on an appeal in 2015. In May of 2020, he completed his parole. Rudy’s published works include Buried Alive: Poetry Born of a Life Sentence and Snippets of Soul in Seventeen Syllables.

PODCAST TRANSCRIPT

Speaker: The following program is a PBS Wisconsin original production.

Angela Fitzgerald: Hi, I’m Angela Fitzgerald. And this is Why Race Matters. According to the Madison school district, 57% of school suspensions in 2019 were given to Black students. Why is that? Large education gaps, poverty levels, and zero tolerance policies are huge issues that affect Black education in Wisconsin. Today. We’ll talk with Rudy Bankston, a survivor of the school-to-prison pipeline who shares his story of being wrongfully convicted and sentenced to life in prison at the age of 19. We’ll explore intersecting themes of identity, equity, justice, trauma, and resiliency. So join me as we explore why race matters when we talk about education.

Well, thank you for joining us today, Rudy.

Rudy Bankston: Thank you for reaching out and inviting me.

Angela Fitzgerald: Of course, you have a lot to share on this topic. So to get us started though, can you tell us your story and how it has landed you in the field, in the area of work that you’re in?

Rudy Bankston: I grew up in Milwaukee, the youngest of four. Grew up on the north side of Milwaukee, and this is the ’80s and ’90s. Attended public education. A lot of busing was happening back then.

Angela Fitzgerald: That means student being bused to other other schools outside their neighborhoods?

Rudy Bankston: Yeah, predominantly white communities. But the first community I grew up in was actually predominantly white. When I first learned what was going on around me, my first buddy next door was a white kid. And at the time we didn’t know much about race or anything. We just rode around on our dukes that was a big wheel. I had the Confederate flag on the back of mine, and no one told me what that meant.

Angela Fitzgerald: You’re out just representing, unaware.

Rudy Bankston: Man, it was fluttering. And honestly, I loved my big wheel, so we probably would have been beefing at that stage if you tried to mess with my Confederate flag, but I didn’t know what it was. But again, I didn’t have any notion of race or anything back there. And we would just ride our big wheels up and down the block, and he would yell, “Stranger” every time he saw an adult, and we would paddle away and whatnot. And my mother would reward us for who got the highest grade point average. My brother ended up beating my sister out. And I recall it was just this frustration on her face. And meanwhile, I’m the sixth grader holding a report card for the first time with a grade point average, because I’m used to ones and twos or something. So I’m like, “What I got?” and she snatched it for me and I beat my brother out.

Angela Fitzgerald: Oh wow so you were the highest?

Rudy Bankston: Yeah. So I’m thinking like, “I’m about to buy me some new shoes or something.” But when that happened with that report card, they ended up taking me out of my class that I was in and placing me in an advanced class. And in this advanced class, I was plopped in. I was just there. I’m almost for certain I may have been the only Black student in there, but I could have been-

Angela Fitzgerald: And this is sixth grade still?

Rudy Bankston: … sixth grade. And I could have been one of the only students of color, but I’m not sure. I can’t recall. But I just remember being isolated in the back of the class bored and just waiting for the class to be over. Because whenever I went out in the hallway, my friends would be in there like, “Man, get out that class, man. Come back to the…” And it felt really good to be welcomed. And around this time too, it was an energy towards those kids down the hall and the new space in the school I was in. And the problem was, those kids down the hall with my friends. And I think the adults, including my teacher at the time, they may have thought they were talking over our head when they talk about those students. But I picked up on that.

Angela Fitzgerald: Kids are way more astute than adults give them credit for. They know what’s up.

Rudy Bankston: Absolutely. And I’m in this classroom and I feel basically ignored for the most part. But when I go out in that hallway, my friends would see me.

Angela Fitzgerald: That’s your community.

Rudy Bankston: And I’m like, “Yeah.” So we started our first student class project, operation get Rudy back to the classroom. And we should have got an A, because by the end of that quarter, I was back at my classroom. It was like a hero’s welcome. And the teachers from the advanced class, they all assume I couldn’t do the work, not really appreciating my need for social connection. So I wasn’t tripping. But by then, and this school, we were those kids.

Angela Fitzgerald: I feel like that’s a word for educators who aren’t necessarily picking up on all of the needs of students that they’re recognizing as advanced, but who aren’t performing in the ways that might be expected in the class. There’s something to that.

Rudy Bankston: And it’s the missing component, like social, emotional needs. I needed social connection. I needed to feel a space of belonging in that classroom. And again, I couldn’t articulate it back then, but that’s what I needed. And the focus was on academics and not on that need, not on why I started coming late because I was feeling connected to my friends in the hallway when I was still in the advanced class. But after I got back in my initial class and the initial hall, we were those kids in the school, my grades went down. And my mother said, “Oh, no.” So she pulled me out of the class, ended up moving us out off of this street called Mill Road, down the street from a school called Daniel Webster.

And by then, I was getting a strong sense of race through my school experience, the energy. And I’m not indicting all educators, but it was there. And I think in a lot of ways they didn’t know these schools were diversifying, and they had not really done any work around race themselves as white educators. So how do you hold this? And they’re showing up with their racial baggage.

Angela Fitzgerald: This has always been the case when you think about public education. Integration didn’t require any let’s level set and do some culture shifts. No, that was forcibly, you’re going to be here. And the racist mindsets persisted.

Rudy Bankston: Yeah. And whiteness is standard. Whiteness is the norm. And anything that didn’t fit inside of that, became the substandard. So a part of how you show up as a racialized human being. If you’re a person of color, that is being judged or denied in a lot of ways. Meanwhile, I’m going to this school Webster up the street. And I think my experience at Wright, at my old prior school, shaped my attitude towards school. It developed somewhat… It was a sensibility, but it was also a sensitivity towards being those kids. And it was same issues that showed up in this new school. Meanwhile, I’m navigating this new community where for the most part, the mothers in this community, they embraced us. But the sprinkling of white fathers, you can just tell. And it included the father of my two buddies next door. Because they were the rules.

Angela Fitzgerald: They weren’t feeling you.

Rudy Bankston: I didn’t really pay attention that much. So it didn’t impact me, I think, like that. But it was a rule in that house next door that I could not be in there, me or my brother could not be over there when the father was home, and I never gave it much thought. So it would be times where we’ll be in their bedroom playing Nintendo and the mother would have to come tell us two or three times, “Hey, your father’s on their way home, your friend should go back home,” and I finally go. But one day I’m over there, and my buddy asked me, “Hey, you want to see something really cool?” I said, “Yeah.” So we go in his room and his room got guns and empty war cannon, souvenirs from war and stuff like that. And I’m looking around like, “Who’s stuff is this?” And they look like, “That’s my dad’s.” So in my head I’m like, “This is why we can’t be here when this dude is here. He crazy as hell.”

So from that point on the mother never had to come get me. I’d be the one to be like, “Hey, I think your pops on the way home, hit it.” He’s like, “No, let’s play this last game.” And I’m like, “Man, I’m out of here.” Because I’m thinking, dude can just blow up the neighborhood. And I grew up on the 18th, so I had something to feed my imagination around that too. One night I was looking out my window and how our house was positioned. If I looked out my bedroom window, I would look in their driveway where the basketball court was in the side house. And one day I’m looking out the window and the father just popped up out of nowhere, and was cussing at me and stuff like that.

Angela Fitzgerald: Wait, he was outside of your house?

Rudy Bankston: Yeah, outside the window. And it’s not too strange because that’s where they drive-through.

Angela Fitzgerald: Okay. So it was part of their property too?

Rudy Bankston:

Yeah. So their drive-through was set right there. So it wasn’t too strange, but it was strange because I’ve not had any interaction with this dude. So I’m like, “What the hell is this dude mad at me for?” But I collapsed to the floor, and my brother, Boo, he’s on the bed playing the game or watching TV. I’m like, “Boo, crazy dude next door.” Boo crazy. He go to the window and started like, “Hey, you better get away from our window.” So I go in the room and tell my mother, and my mother meet their mother, the man’s wife outside. And somehow he found out we had been exchanging video games, and I just know it shook my mother up. And I didn’t know at the time that he was saying some racist stuff, but I knew it shook my mother a bit.

And shortly after that… I don’t recall how long after that. But shortly after that, I was taking the garbage out on the way to school, and somebody had written on the big garage door, KKK. I couldn’t even appreciate what that meant. I couldn’t appreciate what it meant, but I did. I couldn’t wait to run in the house and tell my mother, because I was one of them weird kids that would love to watch people face when they were about to discover something shocking. So I went and told my mother. She came out and she walked and saw. I’m looking at her looking at the garage. And once she saw what was on there, I saw a look on her face that I’ve never witnessed on my mother’s face before

And we got out of there. We moved, no news called, or anything. In retrospect, I think about that. But no news called. Now I’m being bused back out to Daniel Webster, the school I was going to. So I’m still going to this school, but I’m checked out now.

Angela Fitzgerald:

But it’s interesting when you share that story about what was on the garage door, and your interactions with the dad. Because I think that does attention to the more in your face racism that we act like doesn’t exist here. We get that it’s systemic… Well, we’re hoping to draw attention to the systemic and the historical pieces of it. But there’s also these in your face moments that are not… Wisconsin’s not immune to that. But another conversation, literally someone, a young lady that I talked to, she said that Wisconsin is cold Mississippi and that’s an example of that. Just because we’re up here in the Midwest, doesn’t mean that we are immune to people having that racist mentality and that coming out in different ways.

Rudy Bankston: And even though this was back in the late ’80s, early ’90s, it’s still showing up today.

Angela Fitzgerald: I don’t want to put age out there, but you’re not an old person. So the father could very well still be alive.

Rudy Bankston: Yeah, absolutely. But not only that, but the children.

Angela Fitzgerald: They’re taking on these mentalities of things that they’re seeing growing up. So we’re seeing the continuation of these ways of thinking. I didn’t mean to stop you. I just wanted to call attention to that.

Rudy Bankston: No. Thank you. I like that engagement. I appreciate it. For real. Seriously. I’m going back out to this bus back out to the school, and then my mother moved us back to the North side in the hood again. She’s like, “To hell with that.”

Angela Fitzgerald: Because that felt safer.

Rudy Bankston: Yeah. And I’m going to this school… And mind you, so this happened in this neighborhood and my mother is my first love. So when something impacts my mother, that impact me deeply in ways I did not realize until later on. But now, my relationship within this school, because I didn’t have a space in this school to say, “Hey, this happened and I need to process this event.” And the crazy thing is, she sent me to school that day, after seeing that. And I remember sitting in the school, but still worried about my mother. And again, no judgment on her, going to school. But that impacted me and it deepened my curiosity around race. But I was left with nowhere to really talk about it. So I was left to come up with my own conclusions. And it really started shifting how I engage white people, and what I began to internalize about myself.

Angela Fitzgerald: And these are still your middle school years.

Rudy Bankston: Middle school years. So this is still six seventh grade. I’m still going to Daniel Webster. And there’s a wooded area. So, it was the school, it was a parking lot. And it was two, three blocks of wooded area, where students would go hang out. We would sneak out during lunch and just kick it a little bit. Sometimes skip, sometimes just hang out after school in there. Because it was just a place where students went and hung out. And one day there was a group of us in a wooded area with a fake gun. And it was not the serious looking fake guns today. It was a real fake gun.

Angela Fitzgerald: So obviously fake?

Rudy Bankston: That’s kinda oxymoronic , but…

Angela Fitzgerald: Obviously fake gun?

Rudy Bankston: Yes, it was obviously fake gun. That happened one day. And probably the next day, I think it was, I’m sitting in the classroom and a security guard come get me in a classroom. And pulled me out and started talking to me about a gun. And I don’t know what the hell he’s talking about. Because his tone was a real gun. I’m not even drawing a connection to when we were kicking it in the woods.

Angela Fitzgerald: The toy gun that y’all saw.

Rudy Bankston: I’m not drawing any connections. So I didn’t realize what they were talking about till I got into the principal’s office and two police officers are in there. And they thought me in handcuffs, tell me the details. I say, “Listen, that’s a fake gun.” I told them where it was at. It was at home. I told them where it was at. They put me in handcuffs and took me away and locked me up in the detention center. They expelled me from the school.

Angela Fitzgerald: Wait, so this is over allegations around a toy gun that was in the woods at your school, that you were arrested and expelled?

Rudy Bankston: Yeah. Expelled immediately. And I was expelled and I was placed in alternative. I spent maybe two, three days in the detention center. And it was interesting, because I was probably the youngest person in the detention center at that time. So guys would ask me to… Big guys would ask me, “Hey, what you in here for?” And I would tell them I got caught with a gun. But every adult I ran into, I’d be like, “It was fake. Why can’t I go home?” But it was like I was forming this defense mechanism, I got a gun.

Angela Fitzgerald: So you’re not messed with?

Rudy Bankston: Yeah. It was a survival tactic for me from telling them that. So even when I got to the alternative school, people would ask me, I’d be like, “I got caught with a gun.” But it wasn’t on some tough stuff. It was more so survival stuff. Meanwhile, I’m in this alternative school. And this alternative school, everyone in there has had some type of connection to the juvenile justice system. And this became my new peer group, in this alternative school where… Alternative schools in Milwaukee at that time, you had some folks who were really trying, but they were under-resourced and they were seeing some of the worst teachers. And maybe not worse, but teachers with the poorest records.

Angela Fitzgerald: Would go to the alternative school.

Rudy Bankston: Similar to what I’ve experienced in Madison on occasion. But that became my new peer group and it spilled, we kicked it. We started hanging out in this… But this became my new peer group. Meanwhile, my mother working full time, I pretty much checked out. A lot of the stuff that I was experienced in seeing, I recall losing my best friend, Larry Love, in high school.

Angela Fitzgerald: There was nothing for you.

Rudy Bankston: And that was that. And I remember not ever going back into that high school, because we were pretty popular and everyone knew. And I just felt like, I don’t want to deal with that. It was me self-protecting too. I was just carrying so much. By the time I was 18 years old, I was arrested for first degree intentional homicide party to the crime, first degree reckless and dangerous and safety party to the crime. This was during the OJ trial, when I was going to trial. And I was just really understanding a lot more about race and whatnot. But I had two trials. First trial ended in a mistrial. Second trial I had an all white jury, and again, this was at the height of the OJ Simpson trial and the racial divide that was being exposed. Not new, but exposed during that time.

I recall when I was in the County jail, one trial happened where all the white folks found said guilty, all the Black folks or people of color said not guilty. So it was a hung jury. And that was in the news. All this stuff was going on. Meanwhile, I’m on trial facing the all white jury. And I recall one of the jurors, she was trying to exclude herself from doing, and the judge asks why. She said, “I was on a highway one day and I cut off this group of Black guys, and I cut them off.” And I think she said she gave him the finger and they caught up with her and threw a soda out the window and it splattered. She’s graphic. And all the people in the jury pool, they’re looking all sad and sympathizing.

And then she was like, “And they never got caught.” And it felt like in that moment, the energy was like, “This one won’t get away though.” You know what I mean. So I’m there paranoid. I’m like, “Man, this is it.” Meanwhile I get found guilty, and I always say, I’m not innocent in terms of… I fell off into the streets. Talking about the ’90s in Milwaukee, you know what I mean? But I was not guilty of this particular case, but yet I was found guilty and I was arrested at 18. Spent a year in the county jail, fighting the case. And by 19, I was on my way to spend the rest of my life basically in prison. So while I was in prison though, I started really looking at my life, “How the hell did I end in prison with a life sentence at 19 years old?”

I started out angry, frustrated, confused. And then I started reading. My mother went to a Black bookstore in Milwaukee. It was called Culture Connection, and she sent me some books. And one of the first books I got was by Na’im Akbar, and it was a book about human transformation. He did an analogy in the book how you start off as a caterpillar and then you become a butterfly. So that growth stage, and what that’s about. But he did it through pretty much an Afrocentric lens. And I just started doing a lot of reading, and a lot of the reading was convicting. It convicted me a lot, because those words on the page were like mirrors being held up. Because by the time I got to prison, I was in a severe identity crisis.

I had pretty much accepted and internalized and began to live out the stereotypes that I heard about what a Black male is. Through that reading I started to really discover how resilient and beautiful and how much genius Black people hold. And growing up in education always got the slave story. But even with that slave story, I got this as victims. But I started reading new interpretations where the interpretation was like, slavery was one thing. But before the transatlantic slave trade, there were universities in Africa. And there are structures in Africa that aligns to outerspace that folks are still trying to figure out how those things were set up before space travel. And knowledge, it became innate. This is a part of who we are. You know what I mean?

And this is stuff I never learned. And again, even when we got to slavery, the story was different. How much genius and resilience it took to survive, even in some instances, thrive when the world was set up to crush you and make you feel less than. I learned about why we went from Africans to Negroes. And when you rob people or their names, then you can define who they are. And so it was just so much stuff that I was learning during that time. And I began to truly realized that our ignorance is weaponized against us. And Frederick Douglas story changed my life, because-

Angela Fitzgerald: How so?

Rudy Bankston: … that just changed my life. It’s two scenes in particular. One scene was him scheming to educate herself, scheming his slave master’s son to teach him how to read, scheming. How much risk it was for Black people to learn how to read. And back then, if you got caught with a book reading it, you might as well had a pistol today. But it was also a scene in Frederick Douglas’ book, when he was older now and his master’s wife was teaching them how to read. And the master found out and became irate. And Frederick Douglas recalls in his autobiography how the master said, “You don’t teach a slave how to read or write. Because if you teach a slave how to read and write, you will not be able to hold them as a slave. It will be impossible to.”

And that really clicked because it really helped us understand why we were denied that education back then. Because through education, it helps you to have this intimate relationship with your humanity. And when you know you’re a human, you’re not finna accept slavery or oppression. And it’s similar to today, when we know what we’re truly worth, we’re not going to accept. So, it’s going to be some stuff that’s happening downtown with some new artwork on and less glass in the window. You know what I mean? Because you know what you’re worth and you don’t deserve to be disrespected. So just that education piece became critical, but not a white centered education.

Angela Fitzgerald: I was going to say, because when people hear the word education, a certain idea comes to mind. The assumption is like, “Well, we have education.” As you’ve already pointed out, what type of education? What sort of messaging is that education communicating to Black students? And if it’s reinforcing this negative narrative, then how is that going to make that student feel empowered in the classroom? So stereotype threat is a thing, it’s an absolute thing. How was that causing me to view myself in a way that is empowering, that I can then perform well? Or is it feeding these defeatist victim mentalities to me so I don’t even think that I can’t.

And I’m so hard trying to dispute this idea that I can’t, that I’m underperforming. Overhauling education and just confronting how we go about it. Absolutely. Who is it serving? And if it’s not equally serving everyone, then what needs to change?

Rudy Bankston: And not getting so caught up in test scores and stuff like that if they’re not… What are you testing on, according to whose standards? And is this young person leaving education as a young adult a critical thinker, or was this young person treated like an empty vessel, where you just poured information into? So this was my process. One of the only jobs I would take in prison was that over tutor. And basically, I learned how to teach during those during this time because part of my job was to convince men, who were doing life double life, triple life, 60 years, 70 years, 30 years, that education was still important. I’m not coming with, “Bro, education is the future.” They look at me like, “What future.”

Angela Fitzgerald: Right, “I have no future.”

Rudy Bankston: So it was just a different approach, and it just started off. And this happened organically, where I would just listen and hear these stories. And a lot of these stories remain inside me and I carry them in the work that I do. But I would hear these stories, and certain times I would go in my cell and write my mother these long letters of apology, just by hearing their stories and their struggles. And what has been in these would be some of the most intelligent, talented, the prison system is a cemetery of some of the best talent in the world, just sitting there. And a lot of these men would rediscover writing, and music, and philosophy, and just deep, deep stuff.

Rudy Bankston: So that impacted me because that became my thing. Prison does it to you too. I became convinced by the time I was a tutor that my job was to revolutionize the mind of every brother who came in to join. We was going to revolutionize, we’re going to get back into the community. We was going to start the revolution.

Angela Fitzgerald: That was a goal.

Rudy Bankston: That was like freedom dreaming.

Angela Fitzgerald: There you do.

Rudy Bankston: With a little delusion.

Angela Fitzgerald: It wasn’t delusional. Look at where you are now.

Rudy Bankston: Somewhat. Yeah. I was reading the Panthers at a period. And yeah, so it was real. I have a more balanced view, even though I love the Panthers. They have a lot to teach us.

Angela Fitzgerald: I was going to say, I feel like they are put the lane that does that reflect the totality of what they do.

Rudy Bankston: It totally doesn’t.

Angela Fitzgerald: And that’s not fair.

Rudy Bankston: They brought breakfast programs. And breakfast-

Angela Fitzgerald: There was no free food program in communities before them.

Rudy Bankston: … and not only that, but the key part of the breakfast program, you got educated. So you didn’t just come in and get free food, you got educated then about your rights, you got educated on many levels. I think that’s why they became a target, because of that. But, just learning about that and really connecting with these brothers. During that period, it really taught me the importance of relationship and education. And a lot of times our common ground was hip hop music. I grew up on Tupac, and they start showing up saying Boosie is better than Tupac. And I’ll be like, “What?” Then I called my daughter and she was like, “Yeah, Boosie is.” I’ll be like, “What?”

So that would begin the conversation. But the beautiful thing about the story Tupac is his history. And he is rich. He has the Black Panther. His mother was a Panther. Assata was connected. Assata Shakur, she was connected. So this was the beginning. And next thing you know, I’m sliding articles and they’re thinking it’s about hip hop. And next thing you know, is books. And it got to the point where the young dudes gravitated towards me in prison.

Angela Fitzgerald:It sounds like you’re dropping these nuggets. I want to just make sure we’re capturing. Literally, you figured out the hook, to provide education or a source of education to this group of people, rather than just saying, “Here, read this,” and then I’m going to villainize you for not doing it. “Okay, let me figure out what you’re interested in. And then tie that to your interest.” That’s one of those key nuggets around education, which I know we’re going to circle back to in a little bit, but I just wanted to amplify that as well as final hook.

Rudy Bankston: Yeah, music was it. Because a lot of my brothers didn’t have anything but a pen in prison. So many of them wrote music, and they would always bring it to me. They would bring it, “Bro, could you look at this big bro?” Yeah. And I would give them that critical feedback, but I used to teach them grammar. I sell the dictionary, the thesaurus on them. Like, “Man, words are your weapons, the more words you got. How you think Tupac was so cold.” So I would have… You know what I mean? But it was this genuine wanting to see them go home and just rock the world with whatever their gifts. They wrote books and any number of things.

But I also became a target in prison, because I ended up moving to a dorm. And at first, when they moved me to this dorm, it’s like 200, or I don’t know how many. But I’m like, “I don’t want to be around all the…” But then I saw potential, “I’m going to start some groups.” So me and some brothers, we started groups. And man, one day they came and rounded me up, took all my books, my paperwork and send me to the hole.

Angela Fitzgerald: And that’s solitary confinement?

Rudy Bankston: Solitary confinement. They put me in the hole because they would say it’s something else. It was because at noon, after lunch, we over in the corner, we have a dictionary on the table, we have a thesaurus on the table. We’re reading books like Howard Zinn’s People’s History of the United States, and we’re… You know what I mean? And they’re like, “What the hell is going on over there?” It’s plantational. Because it was like, “They’re getting educated over there.” And I went to the hole… I still got the ticket or the conduct report, where they’re literally saying, “He got caught with this Black Panther book.” And these were books they let in. And it’s just bizarre. If you read this, it does seem like some J. Edgar Hoover, counterintelligence programs.

Rudy Bankston:

And I’m reading this, but I got a beautiful sister… I had a beautiful sister, still do. She got them people on the phone, and they reduced my time in the hole. But it was many men getting targeted for filing lawsuits and things like that, that didn’t have that outside support. You know what I mean? And this is what drives men crazy, where you’re literally fighting for your humanity, fighting for your freedom, fighting for things, and you’re being punished for it. And when you get stuck in a cell and just feeling that, because there were time my mind popped in seg. You know what I mean? So they started scrutinizing me for everything I got in, reading material. Well, contraband was certain reading materials.

Angela Fitzgerald: I was going to say in your sense it what you were reading.

Rudy Bankston: It’s crazy. It’s bizarre. And again, I still have the conduct report, because I say this because people would not believe what goes on inside those prisons. And you got to realize many of those prisons are in white rural areas. And this is the first time many of the white folks interface with with people of color.

Angela Fitzgerald: Like the correctional officers and things like that.

Rudy Bankston: Yeah. And they hold a lot of what they heard through the media and things like that. And in many ways, even though the label criminal is on these men and women in prison, in many ways, they are the most vulnerable because they’re isolated and they’re stigmatized. And throughout history, when you think about Black people, when you think about the Jewish Holocaust, those in power had to demonize the folks first to convince the rest of the country, community, or whatever, that they deserve being treated less than human. And it’s similar today with whether you’re talking about “immigrants” or having that stigma of criminalization on you.

So it lives on. So anyway, that’s what I did in a joint. Around 2004, I ended up getting sent to the hole. We were on the basketball court and it got rough. And I was sent to the hole. And I was sent to the hole and sentenced to 360 days in segregation. And I’m like, “Man, get my books and reading material.” And it’s hell. Segregation, the future will judge us harshly on segregation units, because there are dehumanization things. They’re torture chambers. But I didn’t watch much TV and things like that. So I had built my stamina around reading and writing, you know what I mean? And it was still hell, don’t get me wrong. Segregation units are hell. And that was just playing to this chipping away. And I recall one day I was on my bed, and in my head, I got up and went and spit in the toilet, but I spit right on my bed.

But in my head, I was at the toilet and I spit, and I’m like, “Damn! What the hell?” So it was that type of environment. But also when it’s an environment, it was the beginning of my physical freedom. Because I met an educator in this environment named Pat Anderson. Pat Anderson was a teacher, and I would watch her out the door. When she would deliver books, she would come down with her little book cart. And Pat Anderson, at the time she was probably 65 year old white woman. But she refused not to see our humanity. So it would be brothers who would… She would push her little cart to the door and say, “You want a book?” And so she would just get cussed out. But she would understand what those conditions was doing, so she would look this man in the face who just cussed her like, “Yes, but do you want a book?”

Angela Fitzgerald: She wasn’t taking any of it personally.

Rudy Bankston: And not shaking. I don’t know if she was just at that age like, “Whatever, I ain’t scared of you.” But she didn’t care. But she had a heart that in those conditions… And I’m watching her. I never communicated with her. But then someone from another unit who knew I had already written a book said, “Bro, you got to get in this writing class.” And Boscobel, you leveled up out of there. And I ended up leveling up to green, and this was on my second year in Boscobel.

Angela Fitzgerald: And that’s, I guess, your performance for lack of a better term or…

Rudy Bankston: Your duties, programs. Like you do the programs. And anyway, now I’m able to attend class. I attended her writing class. I wrote her and she accepted and I attened classes with handcuffs. We all did in handcuffs. So we all sit in there, and here’s this older white woman just holding court, getting in our face. What she was saying was, “Y’all are human beings. And even if you don’t think you’re a human being, you ain’t going to fool me.” So she just engaged us like that. So I got in her class with an ulterior motive. I had written my first book. And, again, prison does it to the mind. I was like, “All I got to do is get this book in her hand, and she’s going to read it and say, “Oh, my God.”

Angela Fitzgerald: Inspired.

Rudy Bankston: And then she’s going to get it out there and people are going to show up with free Rudy signs, and they’re go have to… Prison does it to the mind, especially supermax prison in Boscobel, Wisconsin. Anyway, we just built a genuine friendship as much as we can have one in those conditions. And it was at one point, she just looked at me and said, “You do not belong in prison.” And this was the first time anyone-

Angela Fitzgerald: Had said that to you?

Rudy Bankston:… those words.

Angela Fitzgerald: And this had been 10 years out of this time. Wow.

Rudy Bankston: No, now it’s 2006. 11 years now.

Angela Fitzgerald: 11 years.

Rudy Bankston: 11 years. And she said that to me with such sincerity. You had to learn in her class, because a lot of folks didn’t realize… I thought I was a writer. I came in their arrogant. I started getting all that red ink splattered on my paper. It humbled the hell out of me like, “Oh, my God!” It became a competition, I’m going to impress her this time. And she didn’t pull no punches, which I love from people like, “Hey, man, what is his?” And I’ll go back. But she taught me how to… She really helped me cultivate my writing. And she also would not edit it for me. She would get stuff. And she started telling me about this thing called the internet, and how it… I’m like, “What?” And while she was describing it, I’m like, “Man,” I started dreaming about getting on this thing called the internet. So anyhow, I mean we would talk politics. I recall it was one time only folks that was left in her class was me, one of my comrades, Hector, which was a Puerto Rican brother. RIP

He ended up dying a couple of years ago after getting out. And it was this white supremacy dude. And it was the four of us. So you got a Black man, you got a Puerto Rican man, you got a white man, who’s a slave by his own racism. And then you got Pat. And we would have these deep conversations. And then it was funny because at certain points before the so-called white supremacist knew who Pat was, he would assume when he would say things-

Angela Fitzgerald: That they had the same belief.

Rudy Bankston: … but boy, she would just… And she would still see his humanity too though. So, I fed off of that, because I’d been doing all this reading, so I’ve been wanting to engage. And I found out she retired, I called my daughter and said, “Hey, what’s that Google thing y’all got out there. Looked his name up.” She looked it up. We found Pat got on my list. I got her my book, my visiting list. We started writing, talking. I got her some of the brothers in the dorm. We helped do a counter report to one of those government reports that came out around this time. And through Platteville, we did… So it was just a lot of purposeful work…

Angela Fitzgerald: But you were to still continue with her even after leaving supermax.

Rudy Bankston: With her and also spread that love to other brothers who were very intelligent. And it felt good for them, because they were able to contribute to something beyond prison. So I sent her copy of my book and I was just like, “Yeah, that’s going to do it. Now I’m back on this too.” And it just came back splattered. I mean, soaking red ink. I mean, it was devastating.

Angela Fitzgerald: She kept up her critiquing skills.

Rudy Bankston: It was devastating. It was funny because I was still rewriting and learning from her, but no. And I needed that love. And this is what I tell educators. High expectations, deep empathy. If you know a young person is carrying trauma, is having a lot of socio-economic issues, anything, you can still have empathy, but still have high expectations. And then oftentimes in the education system, it’s either those who have no high expectations and less empathy, or empathy and just low expectations, which is just as harmful. But if this young person has whatever support they need, support them so they can achieve on the same level as any other student.

Angela Fitzgerald: Exactly.

Rudy Bankston: And Pat modeled that, you know what I mean? So we ended up getting the book together, and she asked me if she can send it to her friend, Dr. Donna Hart-Trevalon. And I said yeah. And her friend, Dr. Donna Hart-Trevalon read the book and she wrote Pat… I mean, she communicated this to Pat and Pat communicated to me. She said, “There’s no way I’m letting him die in prison.” And she stood on that. And it was crazy. Our first visit… All the time I think, is she a white woman? Because she’s Pat friends, she’s living in someplace called Middleton. I ain’t know what the hell Middleton was at the time. Now I do, because I live in Madison. So when I go up on a visit… When I entered the visit, I saw this beautiful Black woman, had a queenly like aura about her. But in prison you don’t be staring at people visit.

I had a cold peripheral game. But you don’t stare. But I noticed it was like an energy, you know what I mean? So I went and gave the guard my slip. And I’m like, “Where I’m at?” He looked like, “You don’t know where your visit at?” I said, “It’s my first time seeing ’em,” and pointed towards this beautiful Black woman. So I walk up to the table. I said, “You Black?” And she looked like, “I hope so.” And that was the beginning. She’s my closest friend to this day. She went to war for my freedom. She went and got the Innocence Project on my case. And they only had certain resources and wanted to do a time reduction, which would have still left me with a life sentences. And we said no. And she went to war and we got the right lawyer on my case. She helped me get my first book published from the joint. And we walked out of that prison in 2015 March.

Angela Fitzgerald:

Wow. So this had been 20 years as of that point about?

Rudy Bankston: 20 years. And I met Donna and around 2007 or eight. She stood on it. And to this day, she’s my closest friend, my mentor, and just a beautiful… I cannot sit here and… We don’t have time. So I ended up going back to Milwaukee for a month. And while in Milwaukee, I just knew I had to leave. It was so much pain, still connected for me so many triggers. I moved out on my own. By then I was working in the education system. I started off at Memorial High School as the community liaison for the peace room, which was a grant. And then, they started another school called Restore. And I joined that team as an actual employee. And then, I ended up downtown. By 2017 or 18, I was working downtown as a restorative justice coach, but doing it through anti-racism lens, and that’s my lens. And that’s the work that I do. So in title I was a restorative justice coach. But when I got downtown and I loved it because I learned so much. I have some awesome colleagues that just understood my struggle. You know what I mean?

Rudy Bankston: And even the principal, Jay Affeldt, who hired me at Memorial, he took a risk. Because a part of me coming home, I took a deal to come home. I could have went back to trial. I could have risked another trial, but they wanted to settle the case, because they didn’t want to retry a 20 year old case and then say, “Hey, we got to deal with it a person who was not guilty of a crime.” And at that time, I was 20 years in. So I said 25 years. I mean, they offered 25 years, which means I will go home immediately. So I accepted the 25 years, came home with five years parole. And I just got off in May.

That’s the work I did. And for me, there’s a lot of institutional fear in public education that I just didn’t get, but it was also a trigger to me. Because when I was fighting for my freedom, that institutional fear from people that truly love me got in the way of me getting home. Because folks are like, “How are we going to beat this system?” So I carry that story and education, and really working with education and educational leaders. I retired from education… Not retired, resigned in 2019. And now I have an LLC, where I contract with educators around wherever, but mainly in Wisconsin. So I contract with Stoughton, who we’re out there doing some really important work. And it’s restorative justice..

Angela Fitzgerald: I was gonna say is it still restorative justice?

Rudy Bankston: but it’s anti-racism lens, predominantly white staff that are just going deep.

Angela Fitzgerald: Well, let me ask you this because… And thank you. Your story, you could get a movie, docuseries, something.

Rudy Bankston: Make it happen.

Angela Fitzgerald: Just lay it all out.

Rudy Bankston: Let’s get it.

Angela Fitzgerald: I mean, we are a media company. I was like, “I can’t do that. Wait a minute.”

Rudy Bankston: Yes, you can. Let’s do it.

Angela Fitzgerald: We can talk about that.

Rudy Bankston: No doubt.

Angela Fitzgerald: But I’m thinking about those who are listening to this and were thinking like, okay, we start off talking about like his time in school, and then we talked about your time within the criminal justice system. I wanted to elevate why it’s so important to talk about those two systems being connected.

Rudy Bankston: Because one feeds the other. My school-to-prison pipeline started in middle school when they said get out. That changed the trajectory of my life. When I got kicked out of that middle school and went to that alternative school, the streets became a part of who… They said get out and… You know what I mean? So that story started in middle school as it often does with young people. Part of the work that I do also, not only where… I mainly work with adults and work with adults around race and racism, and it can be anything from curriculum to development to building just and equitable learning environments, but also contract with the… A part of one of my contracts is working with those young people in the juvenile system right here, downtown, in JRC.

And many of them I’m seeing the same thing in terms of smart, gifted, in unique ways that don’t fit the mold of. And you just want to… How do we pull these resources and get them what they need in order to not… And that was my stance coming home. The assumption of many was that I was going to get into prison reform. But for me, Angela Davis taught me some stuff about what reform is versus abolition. So that was one thing. And I still support brothers in the joint. I still support the cause around supporting freedom of men, women, or however you identify. I still support that. But I came home, I’m going into education.

Because for me, our young people spend more time in these schools and their reality of themselves and the world is getting shaped. And education, it’s always been like… It’s like a serious hit or miss. And it has an impact. And again, when COVID hit, I did virtual… I teamed up with some educators in the juvenile system, and we built a curriculum from scratch, basically.

Angela Fitzgerald: Virtual curriculum?

Rudy Bankston: Yeah. And guess who help do it?

Angela Fitzgerald: Who?

Rudy Bankston: The students.

Angela Fitzgerald: They helped to create it?

Rudy Bankston: Because I would show up, and I would come or… Excuse me, me and a couple of teachers would come with our lesson for today, and I would have a quote by Angela Davis, for example. And they would be like, “Who is Angela Davis?” Inside I’d be like, “Yes.” And next thing you know, we’re watching the 13th. And we’re just constantly… And they would ask me a question like, who do I listen to, music? And they were like, “You listen to Kevin Gates.” And I’ll be like, “Yeah, what’d you know about Kevin Gates.” And the artists that they say they listened to, I would go find interviews, because what you will learn from a lot of artists, they will be on some super gangster tales stuff in their music. Then you go listen to an interview, and they just so deep. And Kevin Gates, he is our golden. Because he’s over here one minute, over here the next.

Angela Fitzgerald: That’s what I’ve heard about him.

Rudy Bankston: You go read some of his interviews, and the thing is, he will be talking about that would coincide so perfectly with the lesson plan. When you talk about making decisions, surrounding yourself by the right people, learning how to respect women when being harmed, because Kevin Gates is real vulnerable. So he would talk about being harmed as a young person through his relationship with his mother, how that shaped his relationship with women and how he began to become basically a misogynist through that, and had to figure out where that drug addiction and how he was trying to quiet the demons.

And so a lot of this stuff… And he would support that. But for me, that’s culturally responsive teaching, because they’re literally giving you… And I think, Paulo Freire talks about how, when you’re a leader of the people or a revolutionary, you don’t show up with all the answers. You show up, you listen to the people, they give you all their thoughts, their wisdom jumbled all up. And your job as the revolutionary is the go and organize that knowledge and wisdom and give it back to the people. And I think that’s the same relationship that has to be done with young people, where you have to show up expecting them to teach you some things. Because they’re going to teach us. A parent and a child, that child is going to teach you how to be a father.

You don’t have to have all answers. You just need to pay attention to what the…

Angela Fitzgerald: That’s being given to you.

Rudy Bankston: And it’s the same with education. But it’s really difficult because if you’re an educator and you’re showing up with all this bias that that society has… When you think about white supremacy culture, it’s the air we breathe, the water we swim in. So we’ve all internalized that. But you show up in a classroom and you’ve not done any of your own identity work, and you’re showing up with this. And then the district is constantly pounding data in your head about how Black kids can not learn. And then they say go into class and teach Black kids. So you have to have some very deep and intentional unpacking.

Angela Fitzgerald: And I feel like sometimes it’s not even data that specifically says that, but it’s the comparisons. So if you’re saying, “That Black students are performing in this way by comparison to white students,” that’s setting a white students as the norm by which everyone else is then expected to level up with.

Rudy Bankston: That’s the very epitome of white supremacy. Because if you’re the norm, you’re the superior. You know what I mean? And if you’re not learning in that dominant way, if you’re not fitting into that cookie cutter approach to education, then that’s how so many people end up in prison with such deep intelligence, that they may learn in unique ways. And if you’re not an educator… And the conditions has to be set by leadership to say, “Hey, you can get creative, but you have to do your work as particularly,” not only as a white educator, because again, people of color, specifically speaking for myself as a Black person, we internalize this stuff as well. So we have to continue to do our own work. The struggle is we’re expected to do the work of teaching white folks, and then also doing our own healing. You know what I mean?

Angela Fitzgerald: And that’s been a consistent theme in all these conversations that I’ve had today, is that, there are folks like you who are in the field doing the work, but that doesn’t absolve you from needing to manage your own stuff. I mean, you had a super traumatic experience for decades. So you’re still having to deal with aspects of what that still means for you on top of how you’re pouring into other people and trying to fix this corrupt system or systems.

Rudy Bankston: And the daily chip in a way of micro-traumas. I don’t want to say micro aggressions, because those are just chippings away. Every time you encounter some slight or anything, it’s a chip’n away. And when you’re working in institutions that are just so rooted in whiteness, that… I mean, I had to create space for myself, because I was carrying a story of institutionalization. And for me, it freaked me out to start seeing the same fear that I saw in the prison system amongst staff who wanted to treat “inmates more humane” and how they would be scrutinized. And I show up in education. I did not get that level of fear. And it really shocked me, and not from a place of judgment, but from a place of how is this living?

But that is capitalistic white supremacy culture, where it thrives off of keeping people in place. Education is more about compliance than really helping students to become critical thinkers. And when you’re focused on compliance, it trickles down. So the principal is compliant with the school district, the school district is compliant with the board, and then the teachers feeling like they don’t have power to their classroom becomes the only place of power. So then now they have to get compliant. And that energy around that, it makes it extremely difficult to have those just and equitable learning environments.

And I think what I’m seeing with the virtual learning, it is creating space. Only if it’s capitalized on, but it’s creating space for educators to do some deep diving around identity, but also it’s creating space for the system as a whole if they really want to do something radical. It was amazing how quick they drop testing when it needed to be dropped. And everybody’s alive. You know what I mean?

Angela Fitzgerald: Nothing bad happened to anyone.

Rudy Bankston: Yeah. But now what I’m seeing in education, they’re trying to pour old wine into a new bottle, a new reality. And principals are burnout, teachers are burnout. Because you cannot-

Angela Fitzgerald: Now working for families, instead of working for students.

Rudy Bankston: … yeah. And it’s Not working for educators. It’s not working for anyone. And you have to learn how to pivot and say, you know what, academics, okay. Testing, whatever. But this is our new curriculum. How to make this more just, how to make this more humane, how to center the wellbeing of human beings across the line, because that’s who I work with, adults in education. And a lot of leadership are burnt out. And they’re expected to be superheroes. So their staff rages at them because they’re not superheroes. Meanwhile, the staff don’t feel supported, and they’re trying to deal with this existential threat.

They’re dealing with work life, professional life overlapping. They’re dealing with learning, virtual learning. They’re dealing with all this different stuff, and you’re still talking about tests and evaluations. How can we make sure the wellbeing of everyone is centered? And how do we make that a part of the curriculum? How do we turn that into lessons? Because one thing that Georgia Floyd and all this other stuff that’s happening, that’s all curriculum. And it’s what’s impacting is what we carrying. So we can create healing environments, where education is anchored into the reality of what we’re grappling with, but it’s also led with heart work. But it’s still that headiness head, and folks are burnt out.

Angela Fitzgerald: I love everything you just said, especially the emphasis on how we can re-imagine. Because since we’ve gone virtual, there’s been little catch phrases about the re-imagining of education and what does that look like. That’s different. And you’re right, but it’s catchphrase you to say that it was easier to default to what’s familiar. So I feel like some folks are trying to transition, but that’s hard to do when the system is structured in a very specific way that this is how education works. But I am seeing like more conversations about how are we centering social, emotional needs, and social and emotional learning, such that we’re not ignoring the realities of our students, and our families, and our staff in this point in history on top of, “You got to figure out what online learning. Oh, yeah. And it’s COVID,” and all the other things.

We can’t ignore the human side of people, which you’ve already too, talked about as a driver behind why advanced learning didn’t work for you. You did not work out in that environment because your social, emotional needs were ignored. So if we keep ignoring that cell, then that’s not going to serve those who we’re trying to educate.

Rudy Bankston: And cell for not only students, but adults.

Angela Fitzgerald: Right, like we treat stuff like it’s just…

Rudy Bankston: It’s for a community, but the threat to radically re-imagining anything are the human, the conditioning around going back to what you’re familiar with. I forgot who said it, but there’s some old philosophers said something along the lines that people would prefer a familiar slavery than an unfamiliar freedom. Because it’s what they’re-

Angela Fitzgerald: They know.

Rudy Bankston: … you know what I mean? Even though it was dysfunctional as hell-

Angela Fitzgerald: There’s comfort in that dysfunction, because at least I know what it is.

Rudy Bankston: … and that is the biggest threat. But that’s the biggest threat to any real fundamental revolutionary change, is you have to conquer that inclination to go to what you’re familiar with, especially when what’s familiar is not benefiting the whole community.

Angela Fitzgerald: Absolutely. I think that’s absolutely one of the takeaways that I think I personally would like people that are watching this conversation to have. So again, you’ve highlighted the issues around school-to-prison pipeline. You gave your own personal story of how that started off. And I hope people understood that entry point and what that looked like and how it just escalated over time, and then how that culminated for you. One of the things I did want to elevate, because you’ve mentioned men quite a few times, is the plight around the school-to-prison pipeline, I’m gonna slow myself down, for Black girls in particular. Because their rates are actually higher than Black boys, but it’s not being talked about. And there are books are pushed out that are trying to call attention to, “Hey, there’s this issue.” But again, it’s not being spoken about. So is there something you can speak to briefly before we close?

Rudy Bankston: Thank you for elevating that. I think it’s still that old belief that it’s just the threat to Black males. But I mean in education, Black girls are being criminalized, they’re being… It’s an adultification of Black girls. I’ve witnessed it. You can have a group of white female students running down the hall, and it’s symbolic. And people wouldn’t bat an eye. But you have a group of Black girls running down the hall, and it’s just ring the alarm. And that’s symbolic. It’s a small thing, but it’s symbolic. I work with our young sisters, particularly… They’re quarantining and in JRC, and our last two students were Black girls, struggling, wanting to do good, wanting to do great things.

But society is mean on our Black girls, and they are being made to feel that they are not smart enough, they’re not pretty enough. And some of it happens within the family, some of it happens through media, some of it happens through school, but they internalize that. And there’s a phenomenon in education where Black girls are fighting, and they don’t understand where it’s coming from. But what you internalize, you externalize, particularly on those who… If you’ve been made to feel like you’re not pretty enough, you’re not smart enough, and you begin to develop some stuff… And I’m not talking about all, because some of our little sisters, they get it.

But there are some of our sisters, they’re suffering and deep ways. And instead of folks asking what happened, they’re asking what’s wrong with you. You know what I mean.

Angela Fitzgerald: Exactly. It’s that lack of recognition around how trauma, however, that has manifested, maybe contributing to what you’re seeing in the classroom.

Rudy Bankston: Yeah, definitely.

Angela Fitzgerald: And how that’s then leading to other sorts of issues in school, which could then land you in the juvenile justice system, and that could just accelerate from there.

Rudy Bankston: And then to be treated as a young person, to be treated as an adult, or treat young people like whole human beings, but give them space to develop. They’re still in the stage of brain development and things like that.

Angela Fitzgerald: We know this

Rudy Bankston: But to not have empathy… Young people don’t want sympathy, they want empathy. They don’t want people to say, “I’m sorry.” They want empathy, because empathy is, “Yeah, that’s terrible, how can I support you? What do we need to do to make sure you still succeed?” And the compassion piece comes in there, because it’s not enough just to be empathetic, because you can stall on empathy and go no further, but compassion is the action part. I’m going to do what I can to alleviate your suffering.

I’m going to do what I can to support you, because you’re dealing with circumstances that are not of your own choosing, and things have happened to you that you don’t deserve, that happen to you… Where people treat you as if what is happening in your life, you deserve it, you began to believe that. And then, that just creates despair. But thank you for lifting that up, and checking my patriarchy and the process. Because it is, and I need that. And it’s not I’m blind to it because I see it, I’ve checked other people about it when they say, “Our Black boys, our Black boys.” No, our Black girls are suffering now. And it’s about creating healing spaces for them, and allowing them to co-create these spaces.

Angela Fitzgerald: Like you said before, not coming in with the solutions and the hero cape on. But saying, “What do you need and what would you like to create that then provides what is it you need.”

Rudy Bankston: Yeah, for sure.

Angela Fitzgerald: Wow. Well, thank you for speaking to that. Definitely didn’t want that piece to go unnoticed.

Rudy Bankston: Thank you. I needed that though.

Angela Fitzgerald: No, it’s fine. It’s this weird juxtaposition of hyper visibility that I think Black women and Black girls in our state, in our city, deal with on a regular basis.

Rudy Bankston: Yeah, absolutely.

Angela Fitzgerald: And constant confronting that I think is what we want to take place here. So I feel like you’ve dropped so many nuggets just during our entire time together. So I don’t want you to feel like you have to say something that’s a close out. But if there’s anything that you want people watching this to take away from, whether they can relate to your story or not. Whether they’re like, “This is new information for me, I want to help.” Or, “I’ve been in this, and I’m trying to move the needle and I’m just struggling.” What do you want them to connect with the most?

Rudy Bankston: I think on the one end, for me, anti-racism work is about tearing down the barriers that gets in the way of us seeing one another’s humanity. And that work is critical during this time, whether you were an 80 year old or you eight years old. And we have to create spaces where we can have these conversations. Healing Justice, they talk about, we hear, we organize, we act. And I just think now more than ever… And it’s showing up everywhere. And a lot of the anxiety is causing, because people have been conditioned not to talk about it. We have to embrace the fact that something happened before all of us were born, and we still carry it. James Baldwin, we’re trapped inside of a history. He was talking about white folks, but I think we all are trapped inside of history, which we truly don’t understand.

And that history inprisons us in a lot of ways. So, it’s in our best interest to really go deep into that history, to unpack and to be brave, and to create, and prioritize spaces, whether you’re in corporate America in a boardroom, or you’re in a school classroom, you prioritize these spaces where human beings can see one another and began to disrupt the barriers that gets in the way of them seeing one another’s humanity. But then, it’s like the mirror and the window, and I got this from the national equity project. Where you got the mirror where you have to do the work within. You got to constantly be looking in that mirror because you’re never going to be woke. And then you have the mirror… I mean, then you have the window, and the window is dealing with the institutional racism disrupting outside.

But when you start looking out the window, you become self-righteous and you become one of them folk, who you’re the most woke and all y’all are slacking on it. But it humbles you when you recognize, I have to do this simultaneous dance of looking in the mirror and looking out the window, doing my work, my inner work, and also looking out. I got an analogy it’s the onion and the orange. And some folk peel that first layer and they think they got the sweetness of being woke, that one layer. But you realize you didn’t read one book, you didn’t took some trainings. And now you build the first layer and you got the orange, and it’s sweet. But I think our mission is onion mission, where you’re going to peel, you’re going to peel, you’re going to peel, and you’re going to keep peeling, because it’s going to be lifelong work, regardless of what your race or your sexuality, or gender is.

And sometimes that onion is going to make you cry. It’s going to make you cry because right when you think you got it, and it’s another thing shows up. And I’m speaking from experience.

Angela Fitzgerald: That is so true. This work is not a checklist. It’s not check box work. It’s like you said, it’s a lifelong continuous commitment. Thank you for that, Rudy.

Rudy Bankston: For sure.

Angela Fitzgerald: Public education is just that, education for the public. The school-to-prison pipeline and other disparities within the education system can have huge negative effects on people of color, especially within the Black community. A lack of representation in classrooms, administrations, and on school boards adds to a list of problems that need solutions. And it’s through stories like Rudy’s, that we learn how these issues affect students and why race matters when we talk about them. For more info on Why Race Matters and to hear and watch other episodes, visit us online at pbswisconsin.org/whyracematters.

Speaker:

Funding for why race matters is provided by CUNA Mutual Group, Park Bank, Alliant Energy, Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Focus Fund for Wisconsin Programming, and Friends of PBS Wisconsin.

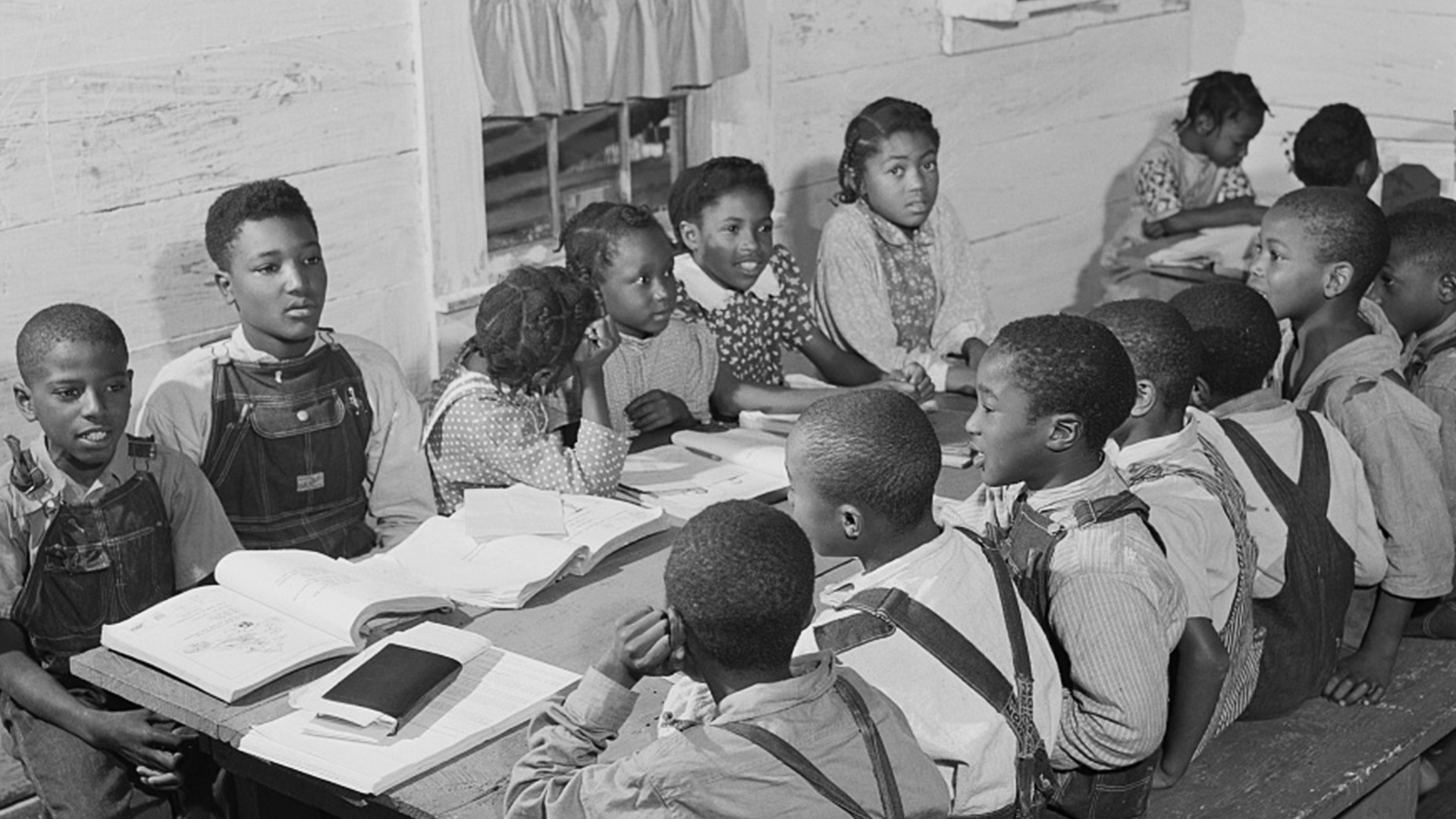

Photo/Jack Delano

Resources

Information on youth mentorship opportunities throughout Wisconsin, learning resources, trauma informed care and further readings on the School-To-Prison pipeline.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us