Mental Health, Trauma and Black Communities

"We can't breathe as a community."—Myra McNair

Mental Health, Trauma and Black Communities

Angela Fitzgerald sits down with Myra McNair, a licensed therapist, to talk about mental health challenges facing Black communities. They discuss images of Black death, racial trauma, the effects of social media and how finding joy can be a revolutionary act. They also look at how media coverage and racism are provoking a public health crisis for Black people.

GUEST

Myra McNair

Owner and founder of Anesis Therapy, Myra McNair is a licensed Marriage and Family Therapist (MFT) and trauma specialist. Myra has a bachelor’s degree in biology and a master’s degree in marriage and family therapy with specialties in addiction, depression, anxiety, infant mental health, parent/child attachment, marriage counseling, trauma-informed practices, and cultural interventions.

TRANSCRIPT

Angela Fitzgerald: Racial trauma has historically been a constant within the Black community, but how have events such as the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, the shooting of Jacob Blake, among others, added to that trauma? What about the almost daily barrage of media coverage, YouTube clips and social media posts showing Black death? How does that impact black mental health? On this episode of Why Race Matters we’ll talk with a therapist about those daily traumas as well as the mental health hurdles that Black people in Wisconsin face. But first, let’s discuss why race matters when it comes to mental health. [gentle music]

The impact of racism on Black communities is not a matter of obscurity, but one of life or death. A 2018 study shows that media coverage, police brutality, and Black death, indirectly affects the health of Black people across the country. With the mental health burden comparable to that of chronic illnesses like diabetes. The president of the American Psychological Association, Dr. Sandra L. Shullman, says, “We are living in a racism pandemic, which is taking a heavy psychological toll on our African American citizens. The health consequences are dire.” The Wisconsin Public Health Association declared racism to be a public health crisis, citing more than 100 studies that link racism to worse health outcomes for Black residents. And yet, only 5% of psychology professionals are Black. So what does an equitable response that supports Black mental health look like? And what are the barriers to treatment that need to be addressed? Licensed mental health professional, Myra McNair, has a few ideas at her practice that are positively impacting the mental health of Black people in her community.

Angela Fitzgerald: Thank you for joining us today Myra.

Myra McNair: Thank you for having me.

Angela Fitzgerald: So, Myra, you’re in your profession because you recognize that this is an issue. Mental health support is an area of need in the Black community. Given that we’re in the state that we’re in, we’re in a pandemic and there’s been a resurgence, thankfully, of refocused attention on the Black Lives Matter movement. But unfortunately, it’s come at a cost in terms of more lives being lost. I’m wondering, from your professional standpoint, what does that mean to the mental health of Black people now? Like it’s a lot for everyone, but for our community specifically, what do you think that means? And how is it even showing up, too, within your practice?

Myra McNair: Yeah, this has been a… This is a huge challenge right now for Black and Brown people but especially, I would say, for Black people. With COVID hitting, it hit our community first and it’s still, it’s, it’s the numbers of how many Black people are dying from COVID and being affected is just, it– it’s just huge, right, the impact. And so, we had that first to deal with with the pandemic, right? And that right alone, just that alone, we were seeing an increase at our clinic for mental health, right? And so, that was a lot.

And then, after the murder of George Floyd, right? He said, “I can’t breathe.” We’ve heard countless Black men say, “I can’t breathe.”

And I always explained with COVID and then with all of the racial unrest, we can’t breathe as a community.

Angela Fitzgerald: [sighs]

Myra McNair: It was almost like we were suffocating. And I think, as clinicians, we process this a lot at our clinic. We were also feeling that, right? Because we have that shared experience but then also seeing the impact in our community, right? And the increase of numbers of people coming in– It was like, we couldn’t breathe.

And that’s the way I explain it. As a community, it’s a shared experience that we’re having right now in the United States. It was to the point, clinically, that I had to even shut down our clinic for a day.

Angela Fitzgerald: Wow.

Myra McNair: Just for an extra day. So we could catch our breath a little bit as clinicians because, like I said, we were having this shared experience with our clients and we needed some time to slow down and for some self-care and processing.

Angela Fitzgerald: I love everything that you just said especially to like the mindfulness that you brought to your staff, because there’s so often– I’ve talked to, like, Black professionals in this city alone, who were like, I have to figure out how to put on the face when I joined my Zoom call because I’m dealing with so much, but because it’s not– this experience is not shared amongst my coworkers.

Myra McNair: Right.

Angela Fitzgerald: Like, I don’t have a space even to process at work. So, I have to file it away, do what I have to do to make it through the day. And then, hopefully, I have another safe space outside of the workday. But the fact that you’ve embedded that because you’re like, “We get it.”

Myra McNair: Yeah.

Angela Fitzgerald: We’re not only supporting, like, our community, but we are part of the community and are being impacted, as well. So, how are we taking care of ourselves so that we’re in a position to be of support and to provide that, like…? because you’re right– being in a pandemic, we can’t all come together like we normally would. And so, what does that look like now? How is that different?

Myra McNair: Yeah.

Angela Fitzgerald: So, I love that you are attentive to that in a way that I think that perhaps other people might not have been as thoughtful around. What do you think are the effects of our being inundated by the media with images of Black death, whether it’s, you know, George Floyd, him being kneeled on his neck until he suffocated? Black men being shot, like, whatever the case may be. On the one hand, those images are put out there to kind of force, to propel people to care. But for those of us who already care, it could be a lot. So, what are you seeing or hearing that you think is a reflection of that impact of those images?

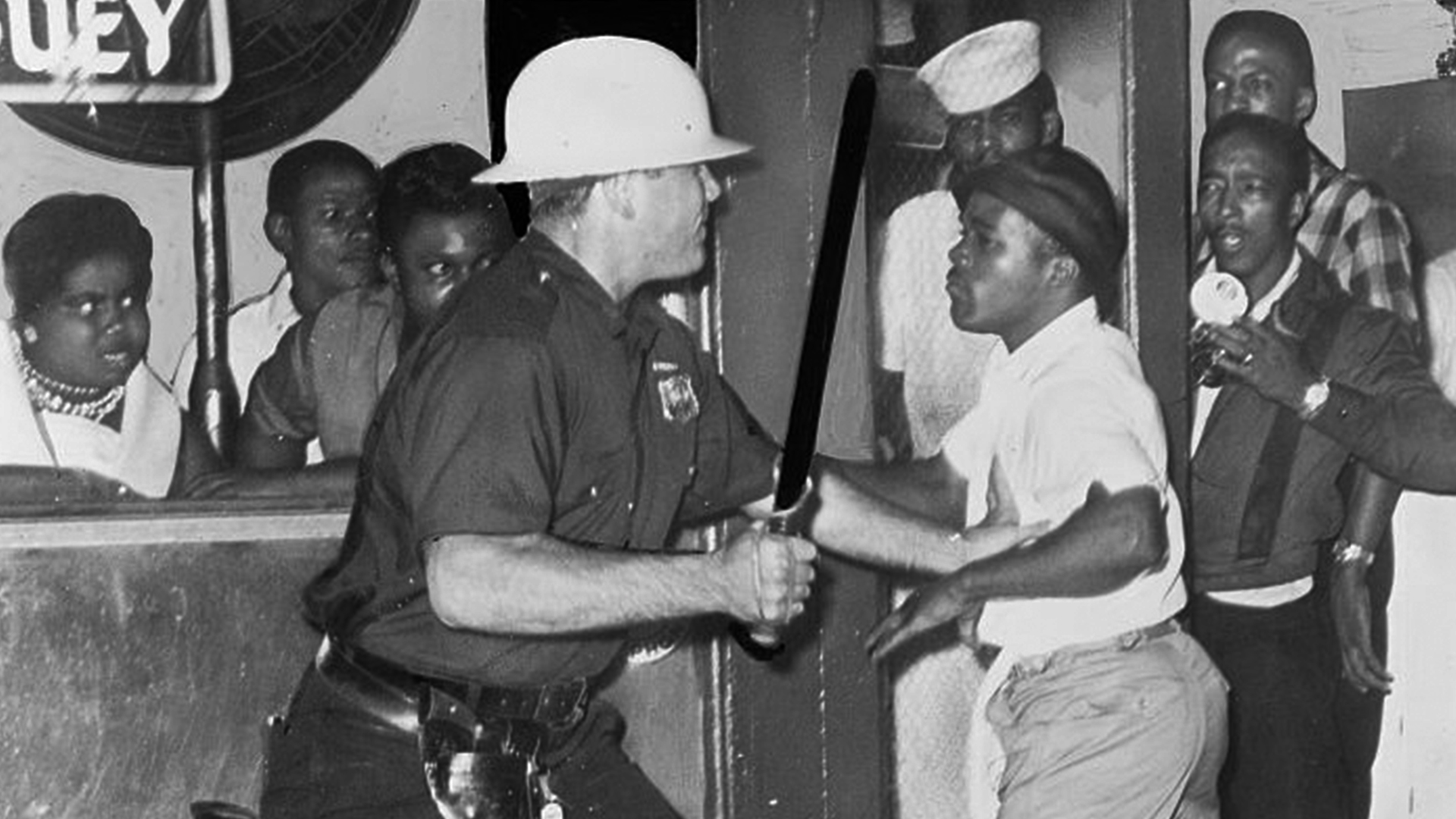

Myra McNair: Yeah, it’s a huge impact. And I would say the hugest is it’s really like a trauma response that’s happening within a lot of Black people that are seeing these videos and they’re being shared over and over and over again. And for a lot of people, sometimes people don’t even know that they’re opening it or they’re about to watch a video like that. I talked to one of my other colleagues in DC who’s actually a clinician and she was so traumatized over Tamir Rice. And she didn’t know what she was about to watch. And literally, like, those images just kept replaying over and over of Tamir Rice and just how young he was. And being a mom, right? And having a son, it’s just, it’s a trauma response. And so, I tell a lot of people to really try to take a step back and take social media breaks because sometimes you don’t know that you’re opening these things or you’re about to see a video like that. And I get that, you know, they’re needed sometimes for education, but I would say, you know, right now, we’ve seen enough. But it’s really hard, I think, for Black people to really just be exposed to that kind of trauma. And it’s not new, unfortunately. This trauma is not new. These types of traumas have been within our communities really since slavery, right? And we talk about lynching and now, we’re, we’re– it’s just a different form of it.

Angela Fitzgerald: Yeah, that’s does feel like the frustrating thing that… The need for this to continue because that was Emmett Till’s mother’s– Like, her whole reason for having an open casket funeral for her son– and we’ve all seen the images of what he looked like– was to show, “This is what you’ve done. This is what we need to change.”

But we’re still then feeling the need to show these images to encourage that same line of thinking. It becomes frustrating. Like you said, it has a super negative and triggering impact.

And on the flip side, I see some folks who are opting out of so closely following certain headlines, and instead trying to put out funny content or other things being criticized for not focusing on the issues at hand, they’re like, I need a break. Like I cannot take this in 24/7.

So what do you say to those who are like, “Yes, let’s pivot, let’s present some joy,” right? In the midst of what we’re seeing as some very, very violent, very graphic, like images of representations of themselves, essentially.

Myra McNair: Yeah, I think it’s a balance, right? Because I think, you know, I have a younger daughter, she’s 18, just turned 18. And for her, when she saw a lot of her friends who are white from high school start like just posting things about cooking and, like, other things like that, she was really offended. She really felt like, you know, our whole community is hurting and we’re grieving and you’re carrying on like nothing even happened, right?

Angela Fitzgerald: Has happened.

Myra McNair: And so, I think that there’s a balance I think for Black people, it is great– I, I have posted myself about restoring the joy, restore Black joy and finding ways to take care of ourselves. Finding ways to have joy in the middle of a pandemic. I would say pandemics for us…

Angela Fitzgerald: Yes, multiple.

Myra McNair: …is really important. So, I think it’s a balance. I think that, you know, to use our social media platform for those different things. But I think also to remind ourselves that we are human and we need joy.

Angela Fitzgerald: Yes.

Myra McNair: We need peace. And it’s so hard for us. I would say so much more hard, harder because we have, yes, COVID, but then we have all of the other things that come with the systemic racism in our nation as Black people. So it’s not so much us being Black but it’s all of the racism that we have to deal with.

Angela Fitzgerald: Absolutely.

Myra McNair: That makes it so hard to find joy and to find peace.

Angela Fitzgerald: Like you mentioned, the structural racism didn’t just stop because of George Floyd and others’ deaths and because of COVID. So you have all the things that were already there on top of what’s being layered on those, those existing issues. So, taking care of self, like I would say, being, like, an intentional act. There are those who might feel like I need to do something. And then there are people outside of the Black community that are looking to us as the solvers of an issue that honestly we didn’t create. So for those of us who feel as though I am personally impacted by what’s happening while at the same time, like feeling this compelled to do something. Feeling this call to action placed on me. That has to be draining. Like, that has to do something to us. So what do you say to that?

Myra McNair: Yeah, I would say it’s really hard, right? It’s a really huge impact on our mental health because we don’t get a chance to pause and heal. And I think it kind of makes sense because we can’t really fully heal when we’re talking about a whole shared experience, right? We’re talking about a collective healing. We can’t really do that until there’s some type of change. So I think it’s really a human instinct to want to say, okay, we got to solve this problem even if we didn’t create the problem.

Angela Fitzgerald: Right.

Myra McNair: We have got to help or create some type of change because we, for the next generation.

Angela Fitzgerald: Exactly.

Myra McNair: There can’t be a healing if this keeps happening, right? Because then we’re going to try to heal and then there’s something else that happens. And then we try to heal and then something else happens right? But it doesn’t make it easy right? And I think it creates a lot of toxic stress. And I always say that toxic stress causes a lot of inflammation in our body, which then causes a lot of other health issues. And I think that’s why we’re also seeing a lot of issues within our community with health, as well as mental health too.

Angela Fitzgerald: [Sighs] So it’s just managing that maybe expectation of even though, yes, you want to solve this for your own children, for generations to come that the approach may need to be managed to not create those other sorts of health problems that you’ve mentioned.

Myra McNair: And I think, again, it goes to balance right? And creating this balance and making sure that yeah we are making things better for our next generation as much as we can and as much as we have the power to do so. But I think also we do have to push back within the white community right? And say that, you know you really need to create change. This just can’t be on Black people.

We didn’t create this system. We didn’t create racism, this can’t … And also, us letting white people in [Angela laughs] on some of the movements, right? Because knowing that this isn’t our movement, this is– this has to be all of our movement, right? This change has to be with all of us.

Angela Fitzgerald: Yes, and historically, that has happened, right?

Where there were white people who took part in the Freedom Rides, for example, and lost their lives alongside those who were Black that were part of that movement. So, absolutely, this is not just our issue right? It’s all of our issue, and we didn’t create it, but we need everyone involved to help solve it.

Myra McNair: And, and creating change happens on a lot of different levels. I tell a lot of parents, sometimes the biggest change and the most like revolutionary thing that you can do is just playing with your kids which I know sounds like really like crazy. But yeah, like in a pandemic during racial unrest, letting our kids, in the next generation have joy, is not what society is telling us right now. And so that’s why I say it’s revolutionary, right? Is to just love each other, love our families, love our kids, that is creating huge change. I tell people, it may not– you may not be a protester, right? Because maybe you’re with your kids, right?

Angela Fitzgerald: Right.

Myra McNair: Or you can’t just drive to the next city and protest with them because you got to get your kids to bed on time [laughs] for their virtual school lesson the next day. And that is revolutionary. That is creating change, in your own small way.

Angela Fitzgerald: I love that. Like, reframing what revolutionary acts are because you’re right. Protesting, marching, all of those acts are appreciated. But for those who can’t do those things for whatever reason, what can you do that still speaks to like self-care, love, joy, all the things you’ve mentioned.

Myra McNair: Yes.

Angela Fitzgerald: Oof! Okay, so I have another question for you,

Myra McNair: Okay.

Angela Fitzgerald: For people who were formerly like myself, who are on the fence about pursuing therapy because as you mentioned before, even understanding that there is an issue psychologically is sometimes lost on us because we’ve never exposed to ‘this is what anxiety looks like,’ ‘this is what depression looks like.’ And we may call it something else.

Like, I very specifically remember experiencing a panic attack in school years ago. And I didn’t know what it was. I thought I was having a heart attack at like, I was maybe like 22. And I went to the ER at the time, the city that I lived in, and they asked me if I use cocaine and I was like I’ve never used drugs in my life, no.

[Myra laughing]

And so, they were like, we don’t understand why someone your age would be having a heart problem. They never asked me about school. Like that eventually came out. They were like, “Oh, okay. You’re a student so this is probably why,” but that didn’t click to them to ask me before they asked the drug question right. And it didn’t click to me that that was probably a connector. And so, even after having that issue it didn’t register like, “Oh, I should probably talk to someone.”

Now, like 10 year– plus years later, I’m– now have a therapist relationship.

But for so long, because, I think, the influence of the church, like praying things away, as well as just not seeing myself as having a high enough need to go talk to someone. Like, all those things kept me from having a relationship that I think would have been super helpful. Who knows where I would be now had I had a 10-plus year foundational relationship with a therapist?

So, in saying all that, what do you say to people who recognize that, “Yeah, life is tough. “I get stressed sometimes. “But you know, it’s– everyone’s stressed, you know, that’s– or everyone has these issues.” What would you say to them to maybe encourage them to consider that: Yes, you’re stressed. Yes, everyone’s stressed. But the therapist relationship could also be beneficial to you?

Myra McNair: Yeah, I would say, you know whether it’s big or small, right? Everyone can benefit from seeing a therapist, seeing a counselor. No one, no doctor would ever say, wait until you’re having a lot of issues before you come in for a checkup or we want you to come in when you’re having a heart attack. You know, that’s when we want you to come into the hospital. No, no doctor would ever say that, right?

[laughs]

Angela Fitzgerald: Hopefully, yes.

Myra McNair: And so we, I would say the same thing for, for families, for individuals to come in and seek help, seek support. Even when you don’t think it’s that big of an issue. And, and what we kind of, that narrative that we tell ourselves so what is big or not? Also comes from your upbringing, right?

Angela Fitzgerald: That’s true.

Myra McNair: And so, someone else could think that is really big. Or you could look at someone else and compare yourself to someone else and say, “No, that’s a big issue,” right? And so, normalcy is all what we think it is.

Angela Fitzgerald: Right.

Myra McNair: Right, based on our upbringing, based on what society or our own community has told us. And sometimes when we go in and see a therapist, we get a different perspective, right? And someone can say, “No, that is really stressful.”

And you can, you know… Sometimes it shocks people, like, “Wow, it is? I didn’t realize I was walking around with this stress. So, I was walking around with this issue that I just thought I was supposed to have it.”

Angela Fitzgerald: Right.

Myra McNair: Right, because we were taught that it was normal, or this is what I’m supposed to be dealing with. Or maybe you saw a parent that was really kind of– had a lot of anxiety, right? And sometimes, we pick up on those things, right, from our parents. And we don’t even know that. We just think, “Well, I thought that’s how it was supposed to feel.”

Angela Fitzgerald: How everyone… right.[laughs]

Myra McNair: Everyone walked around stressed like that, right. And so, I think it really gives perspective. It just, it creates a better you and that’s different for everyone.

Angela Fitzgerald: [sighs] So, there’s still more work to be done. But it sounds like there’s still like hopefulness, like within the midst of the challenges, which I appreciate, which is always been at the core of our community.

Myra McNair: Yeah.

Angela Fitzgerald: Thank you so much, Myra.

Myra McNair: Thank you.

Angela Fitzgerald: The constant stream of negative messages and images associated with being Black is honestly exhausting. On top of this trauma, many within the Black community are also tasked with leading the charge on social justice. This daily struggle can be devastating for Black mental health, which is why race matters when we talk about it. But there are ways to get help, people like Myra willing to listen, and the reminder that finding joy is a revolutionary act.

To learn more, go to PBSWisconsin.org/ WhyRaceMatters to find additional links and resources to help keep you informed. There, you can also check out the Why Race Matters podcast, as well as additional episodes. [upbeat instrumental music] [gentle marimba music]

Speaker: Funding for Why Race Matters is provided by CUNA Mutual Group, Park Bank, Alliant Energy, Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Focus Fund for Wisconsin Programming and Friends of PBS Wisconsin.

Photo/Library of Congress/Dick Marsico

Resources

Access a collection of mental health and support services available in the state, crisis intervention resources, online mental health resources, and ways to celebrate Black joy.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us