– Announcer: The following program is a PBS Wisconsin Original Production.

– When you think of Black art, what comes to mind? From paintings, to sculpture, to film, it provides a medium for conversation and reflection. It can bring attention to serious issues and create momentum for social change. But it’s also a place to celebrate culture and community. Today, we’ll talk to an artist who explores identity in their work. Let’s find out Why Race Matters when it comes to art and Black joy.

Black visual art has a rich history in the United States. When Black people were forced to come to this country, many could only make utilitarian art. As time progressed and Black people fought for their rights, they became painters, sculptors, and embraced other artistic mediums. For some Black artists, joy is fundamental for their art-making process and for the reception of their work.

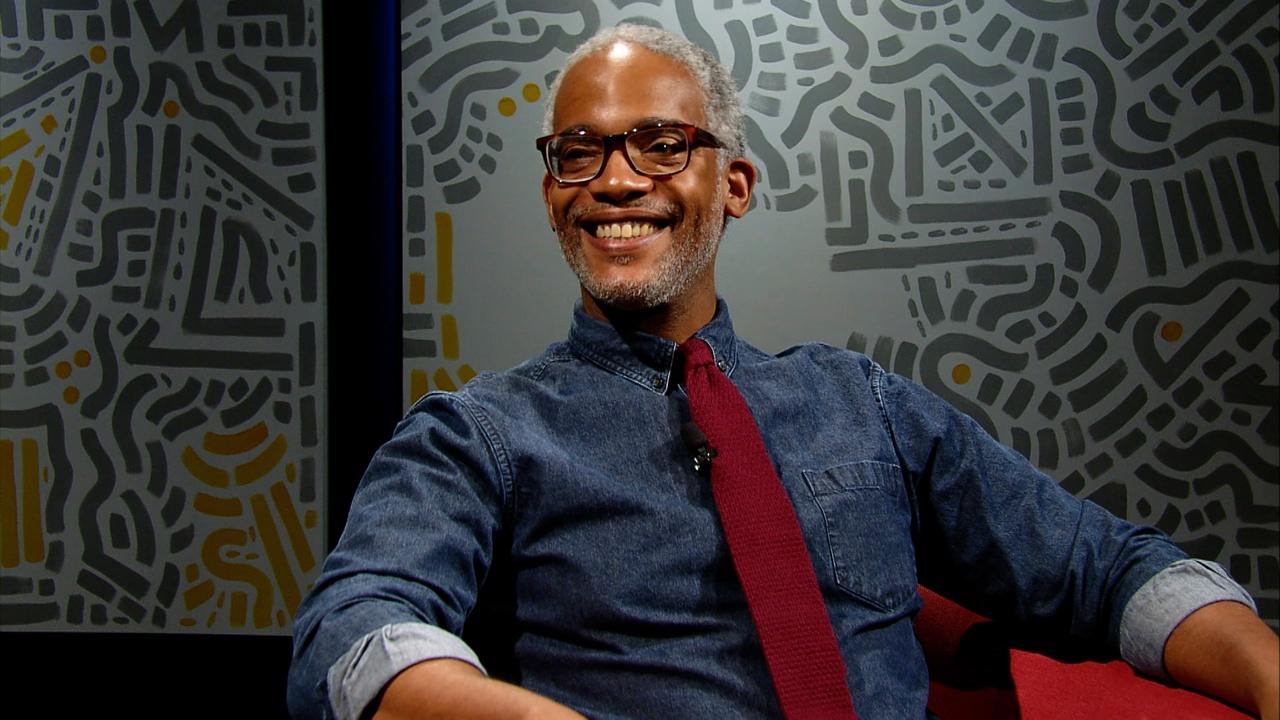

In this episode of Why Race Matters, we’ll talk to Anwar Floyd-Pruitt, a Milwaukee-based artist. We’ll discuss his practice, the importance of community, and the intersection of Black art and joy. How are you doing today, Anwar?

– I’m well, thank you.

– Good, good! And thank you so much for joining us for our conversation today.

– My pleasure, and thanks for having me.

– So, to get us started, I feel like you’re a multi-hyphenate who does things in a lot of different arenas. So, what might be the simplest way for us to introduce you to our audience? Like, how would you like to be described?

– I have to write bios all the time and they’re constantly shifting.

– Angela: Okay.

– I would say that I usually say that I am an interdisciplinary artist from Milwaukee, Wisconsin…

– Mm.

– …working in community arts, performance, and self-portraiture.

– Hmm, okay, I love that! So, can you break that down? Like, what is interdisciplinary art?

[Anwar exhales]

– Well, you know, many, a lot, you know, I’ve been in art school or was in art school for 7 of the last 10 years. And so, a lot of my classmates and professors were very specifically focused in terms of their medium. People working in metals, people working in ceramics, people working in printmaking or painting, and I’ve tried them all. And at this point, I haven’t landed on a single medium that feels most like home.

– Mm-hmm.

– And so I continue to, you know, just work across medium. And I found that I was sitting in my studio one day and I wanted to build a people-powered kinetic sculpture. And I spent some time. I was twiddling my thumbs and kind of going through my brain and I thought, “Huh, it sounds like a puppet.”

[Angela laughs]

And so, that’s how I got started in puppetry.

– Angela: Got it; Oh, wow. So, you literally have, it sounds like skill sets that are broader than just one specific area. So, kind of spreading yourself out gives you the creative freedom to explore those different areas, puppetry being one of them, it sounds like.

– It’s not really about like the fear of being pigeonholed as much as I haven’t landed on, like, a singular definition myself. And so, I, you know, I’ll embrace them all, particularly when there’s an opportunity to sort of share that knowledge or creative spirit because every time I teach something, I also learn something, particularly when working with young people. I had done some work with incarcerated youth, both here in Madison, as well as in Milwaukee. And I just knew, I learned that, you know, that there are some kids there who are sort of like chronically incarcerated and it is, you know, it’s a system that we live in as well as sort of maybe lack of support when they get out, you know, that leads to that revolving door. And then, I also– but I met some kids who were like really, really engaged in the arts. And I could see that when I would bring art experience to them, particularly, this puppetry experience over the last couple years, their eyes would brighten up because it’s fun. For one, it allows them to be the visual artist. And then there’s a– I designed these puppets to be easily… easily designed, fabricated. So anyone with $5 at the dollar store can make, I think, their own puppet show and–

– Angela: Really?

– Yes, and go perform for children’s events. And so, that really excites me to offer something to someone that they can take and make their own, and puppetry is that.

– I feel like you touched on so much in terms of like first expanding, I think, the mediums that are included when we traditionally think about art. Like, I would not have thought about puppetry, which I’m thinking like Sesame Street and like those sorts of like, you know, Jim Henson. Like, that’s my point of reference for puppetry. I would not have thought about that as an art form, but the way that you frame it, it very much is. But I also appreciate how when you describe your community and performing arts work, it’s also broadening like what that means and tugging us in the direction of talking about access because these incarcerated youth might not be the same people you see in an art museum where your medium is available. Like, you’re taking it to them and in doing that, they’re being exposed to, like, a form of art that they might naturally connect with and who knows where that could take them.

– Yes, and it’s one of the things I love about working with, you know, young people or just working with, you know, other artists or creative minds in general, is that epiphany. We’re kind of talking about that. And I can see a young person engaging with, like, the puppetry perhaps, or, you know, the writing of, you know, family-friendly rhymes as something that really says, they think, “Wow, there’s an opportunity in this. “I can see this as, you know, as marketable, as a way forward, as a way to, you know, express myself.”

– So, I wanna shift gears for a bit and kind of talk about the art world in general and the significance of art, especially Black art, and within this particular period of time that we’re in now with just so much happening. The pandemic, so we’re navigating our way through that still being a thing, even though, thankfully, you know, safety restrictions have lifted a bit as of this point. We’ll see if that remains. But also, just all the racial unrest and things that have been happening nationally, as well as within our state. What do you see is a significance of Black artists as it relates to telling the story and conveying, in some ways, the struggles while also highlighting the celebrations that take place within our culture and racial group?

– Absolutely, absolutely. That, you know, that question makes me think a lot about my educational experience over the past few years. And, you know, when I did my BFA at UW-Milwaukee, entered as a 36-year-old freshman.

– Angela: Love it.

[laughs]

– And, you know, but I’m from Milwaukee. And a lot of my work in that sculpture department was about race, was about some of the struggles that I saw in the Black community in Milwaukee after moving back to Milwaukee from New York City. And one of the things that was great about it is that I felt like I could make work about the Black community, but then also for the Black community, because I was, you know, certainly like I was deeply ingrained in the Black community in Milwaukee, through youth work, as well as just my whole family. You know, my whole family is there. And that made it easier for me to make heavy work ’cause I had a support system, you know. When I moved to Madison for grad school, there were fewer– I wasn’t connected to the Black community in Madison as much. My family wasn’t here. There weren’t many Black students or faculty. And so, I really had to make this decision about if I wanna make work about this sort of these heavy topics and do this heavy lifting. Do I have the support, you know, when I leave the studio, when I go home, when it’s time to start, like, writing the artist statements, dissecting it, sharing it with my class in critique? And am I willing– Am I prepared to have someone critiquing the work who’s from…

– Deeply personal.

– …which is deeply personal, but that’s what grad school is all about. It’s about that critique. And it wasn’t necessarily that I was going to shy away from that critique completely, but I just knew that I was, like, in this for the long haul and that I didn’t want to leave graduate school exhausted and in a terrible mood.

[chuckles]

– Angela: Mental health matters.

– Anwar: And so, and mental health matters incredibly. And so, what I decided to do was make it a little more personal. So it’s still my work, a little more personal. So it’s still about Blackness because I was working in self-portraiture. So as much as it, for me, it was about family, you know, history, family history. And so, there’s that family component that locks it in as something personal, but then there’s that history component that we all share, you know? So, it’s an interesting way to sort of talk about some racial issues without the… without the main focus of it being racial issues, but more being my family’s personal story, which is certainly sprinkled with, you know, experiences related to race and racism, but also sprinkled with experiences due to, like, geographic location, you know? My mom’s from West Virginia.

– Angela: Oh, wow.

– So then there’s like, you know, some West Virginia pulled into the work that isn’t specifically racial, but the way I sort of approach that is these are all these different versions of myself. These are all the different people who I have the potential to be or could be. This is the sweet son, Anwar. This is like the Anwar who’s upset that the Bucks lost.

[laughs]

You know, these are, this is the uncle. This is the, you know, the student. And just really broaden the definition, I think, for myself of who I am in this world, who I will be, and let other people know that they also have those options.

– That is so beautiful. And I love how you kind of combine this idea of like, there is depth within what you are sharing. There’s a lot that is packaged when you have so much, like, history and culture embedded within your work, but there is lightness as well. There can be joy as well. There’s a celebration. So it’s not an either/or. It can be both. It kind of depends on the interpretation of the viewer, but for you, as the creator, that’s what you’re essentially embedding with what you’re creating. And what you take from it, you know, you can’t control that, but at least this is what is– what I’ve put into my work.

– Absolutely. You know, it’s a celebration of self, a celebration of family, a celebration of overcoming struggles. And, you know, some people would say that just being Black and alive in America is a revolutionary act. You know? That to be Black and alive, and full of joy is a revolutionary act. And I don’t consider myself a revolutionary all the time. It’s not like a badge that I wear, but if I can contribute to… If I can contribute to sort of to positive feelings, as well as, you know, the deep conversations that are complicated and… and, you know, that hurt sometimes. But I also want to see our people smile. I wanna see people smile at us.

– That’s super powerful. And I love how you are taking upon yourself that responsibility of putting your work out there, even at the risk of it maybe not being understood or received in the way quite that you had envisioned that it would be. It kind of goes back to your school experiences of like, the critique, how you’re putting things out there in grad school, because they’re potentially subject to critique and that helps you. I think the goal is to help you improve as an artist, but that can be hard to take. So, multiply that times a thousand, million, trillion on social media, where it’s definitely open to critique. What did Erykah Badu say? “I’m an artist and I’m sensitive about my stuff.”

– Yeah, absolutely.

– So, it’s that thing of you pushing past what could be those negative aspects of social media engagement because of responsibility and the impact, the positives there, the potential positives there are so much greater than whatever those bots or those trolls might have to say.

– And I think, you know, it sort of brings me to another show called “Collateral Damage” and it’s a show about mental health. And I have three self-portraits in that show. And I would say that that is some of the most challenging work for me right now to have up because it does bring up these conversations that are quite uncomfortable revolving around, one: mental health and mental illness. But then also ’cause my work in that is specifically about PTSD and an experience I had on State Street while painting a Black Lives Matter mural. So, yeah, so it’s, you know, it’s complicated, but it’s important because, you know, well, one: men and mental health. You’ll find fewer men seeking help for mental health concerns. And so, I think in that sense, it’s important for me to be in this show.

– Absolutely.

– To show that men also deal with mental health concerns, which actually puts my experience on State Street at this strange intersection that has been something I’ve needed to think about a bit recently after giving an interview about the “Collateral Damage” show is that I was painting a Black Lives Matter mural, someone who is self-identified as a vet, but I can only identify them as a drunk, white man, older than me, in the middle of the day, came up to me and said, “Well, you know, why doesn’t my life matter?” I was holding a large stencil that said “Black Lives Matter” many times. He came up and he attacked me. And in the end, he damaged the stencil.

But it was the middle of the day right there outside of the– I guess, the Warby Parker at State and Gorham and… you know, he kind of rushed into the bus stop, attacked me. I punched him once in sort of self-defense.

And, mind you, I am 44 years old. I was 43 at the time. Maybe I was 42. I’d never punched a person in my entire life because I am still a man of peace and I’ve lived this peaceful life. And I guess that also speaks to a certain amount of privilege to not have been attacked.

– Angela: Not have to fight.

– Anwar: But is that really privilege?

– Angela: I guess it depends on who you ask.

– Anwar: It depends on who you ask, right?

– But I think to some extent, yeah, because if you’re in an environment that’s not, where you aren’t consistently having to engage with violence, then absolutely.

– Anwar: Sure, sure, yeah, yeah. I mean, it’s what I would wish for everyone. To not have to constantly engage with violence. And so, you know, I punched this man. There were three young Black men on the bus stop who saw that go down and they were, you know, were willing to jump in and help me. And I was like– I stopped them from jumping in, you know? And then the guy yells, “Well, I’m a veteran! Why doesn’t my life matter?” And…

[exhales]

– Angela: So that’s what provoked the attack was his perception that your sign signaled to him that his life didn’t matter?

– Anwar: Right, right. And what a failing. What a failing on part of our community, on the part of culture, right? What a failing on the part of whoever are supposed to be his resources so that he thinks that his life does matter. Believes that.

– Right.

– And you know, it left me, and again, you know, 42 years old, never really been in a fight like that.

– Mm-hmm.

– And it left me not wanting to go to State Street.

– Right, because you didn’t feel safe.

– Anwar: It contributed to me leaving Madison.

– Wow. And you know, what’s funny about that in a, not literal “ha-ha” funny, but ironic funny, is you mentioned you’re from Milwaukee. I think the perception could be that like that’s the scary city by comparison to Madison.

– Sure.

– And you’re like, “No, this made me feel unsafe. Henceforth, Madison as a city

– Right. Feels unsafe to me.”

– Right, right. The pieces in “Collateral Damage,” one of them is called “State Street State of Mind.” And it’s a self-portrait, and I’m kind of turned to the side. My head is down, and it’s like how I was navigating Madison and State Street after that incident. Very suspicious. I haven’t spent much of my time being extremely suspicious, you know, looking out for that person lurking, that danger, you know, right there. And that was my experience after that incident on top of living by, near the police station. So, my neighborhood, you know, being sort of ground zero for a lot of noise, a lot of police, a lot of activity, a lot of fights. And then, we went into that first COVID winter and that was, you know, and it was very lonely. So, then one of the pieces in that show was called “Mired-Winter Wallow,” where it was, you know, the first winter after this incident. My hand was broken because I don’t punch people. So, I didn’t use a very good technique.

[chuckles]

And, you know, and I look at that piece and I think about, mmm… not to– I think about my responsibility for my own health. You know, I spent a lot of that winter alone, which was actually kind of had to be the case. We were isolated, you know, due to the pandemic. I was just living with my cat, but probably didn’t have to drink as much as I did, you know, as, like, sort of this like coping mechanism.

– Angela: Right… from that feeling of isolation, as well as the trauma you had experienced prior to that point, it sounds like.

– Yeah. And, you know, ’cause the neighborhood was always loud and I had some like rowdy neighbors who also were, sort of, some suffering from, like, mental health concerns. So, one of the paintings is like my face sort of slightly obscured by these white lines that looked like Venetian blinds, you know?

– Angela: Like peering out into the world?

– Yeah, and like, what’s going on outside of my window? So, you know, as much as this show is not about race, these specific three pieces are 100%-generated by my experience of racism on State Street. And the work doesn’t necessarily push into this so far, but not just that singular incident, but a series of incidents that led up to that from, you know, and it’s what I think is like sort of complicated for white Madisonians perhaps– I don’t know ’cause I’m not one– is like, yes, this guy who assaulted me was drunk in the middle of the day. I don’t know if we’ve all seen him, but that’s like a certain portion of the population who we’re expecting the poor behavior from, perhaps.

Whereas, I’d also been, you know, verbally assaulted or threatened by, you know, white Madisonians on, you know, expensive bikes in their Greg LeMond Tour de France outfits, right? So, I wish it was just localized. I wish I could point to a person suffering from mental health concerns, a person who is dealing with some sort of, you know, housing insecurity and say, “Well, that’s where the problem lies.” And I think that’s what makes some of this work complicated for me is that the problem is bigger than that.

– Absolutely.

– It’s just a pretty easy scapegoat to point to.

– Mmm… you’ve said…

– And that’s where I get, like, that’s where I’m kind of getting fired up about this work in particular. And have like largely chosen not to, you know, not to talk about it too much.

– Angela: Because there’s so much, like, I didn’t expect you describing your artwork to lend to this whole backstory and this whole set of experiences that like, I wanna give you a hug,

[Anwar laughs]

like, are pretty traumatizing. I’m like, I’m sorry that you experienced that and you were not doing anything that I guess is explicitly harmful to anyone, but yet it elicited that particular response and how even you mentioned that the series itself isn’t about race, but as a Black artist, you can’t extract your lived experiences from the work that you produce.

– Right. So, it’s all gonna go together.

– Yeah, it’s all woven in there.

– Angela: Right, it all goes.

– It’s woven in there.

– Angela: As well as like our bigger need to talk about, like, mental health and what are the nuanced ways that we can talk about it that don’t minimize personal responsibility. ‘Cause I think that’s where it gets tricky. ‘Cause we could say like, “Oh, racism is a mental illness,” but then we’re all mentally ill from that standpoint.

– Sure.

[laughs]

– Angela: And then, where does responsibility fit into the equation? So, I think that does generate a good entry point to talk about like what is actually going on if I’m getting these same or similar sets of responses from these different vastly groups of people? Like, what’s the commonality here that we can kind of address and where does mental health fit into the conversation?

– Anwar: Sure, sure. I mean, and I think in this debate right now about critical race theory in Wisconsin and it sounds like some people are worried that teaching critical race theory will put their white children into a place of mental duress. It might negatively impact their mental health.

– Angela: Right, so we can’t remove mental health from the larger topic of, like, we need to address these are systemic, historic issues that are still pervasive and we’re not really doing a good job of dealing with, so how do we do that in a way that doesn’t ruffle feathers, but I guess it’s okay to ruffle. But how do we move things forward?

– Right, right, right.

[Angela laughs]

We can’t even have the conversation because someone’s feelings are gonna get hurt. Yet, my lived experience…

– Right, like, your physical safety is…

– Anwar: It’s okay for me to constantly, you know, to deal, to deal with those situations about racism. So, it’s, you know, it’s going to take, I’m not gonna say an artist, but it’s going to take an artistic approach to communication to get people… on board, to get people to perhaps find the common ground, to get people to find a way forward that, well, unfortunately, there’s no way forward without people getting out of their comfort zone.

– Right.

– And so, if we’re gonna even try to create a way forward where people don’t have to leave their comfort zone, then we’re actually not. We’re actually not trying, or we’re not putting our efforts, our eggs in the right basket.

– Angela: Absolutely. It’s “Whose discomfort are we prioritizing?

– Anwar: Sure.

– Anwar, thank you so much. I was gonna ask you if there’s any, like, closing thing you wanted to share. I feel like you kind of gave us a mic drop moment already, but if there’s anything that you would like to say to those who are watching.

– I… Wow.

[laughs]

– If you had nothing else, it’s fine, too.

– Yeah, I guess I don’t. You know, it all usually comes out sort of fluidly. And maybe I’ll prepare a pithy closing statement moving forward.

[laughs]

– Angela: For next time.

– For next time, yes.

– Thank you so much.

– Thank you. This has been great.

– Same. Art is inherent to Black communities, yet at times, art is not supported as a medium for self-care with financial setbacks preventing Black people from fully diving into the arts, creating generational setbacks. Despite this, Black artists still find ways to create impact with their work while instilling joy, confidence, and wellbeing. Watch additional episodes at pbswisconsin.org/ whyracematters.

[melodic chime music]

[lively string music]

– Announcer: Funding for Why Race Matters is provided by Park Bank, CUNA Mutual Group, Madison Area Technical College, Alliant Energy, UW Health, Focus Funds for Wisconsin Programs, and Friends of PBS Wisconsin.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us