Wisconsin Workers, Chicago Commuters And Cost Of Living

Cost of living isn't a standardized, hard-and-fast mathematical concept. Looking into how it's defined and applied to specific places reveals less about empirical economic differences and more about the nuanced and fluid ways in which people make decisions about money and opportunity and lifestyle.

By Scott Gordon

March 6, 2018

WEDC workforce ad mockups for Facebook on smart phones

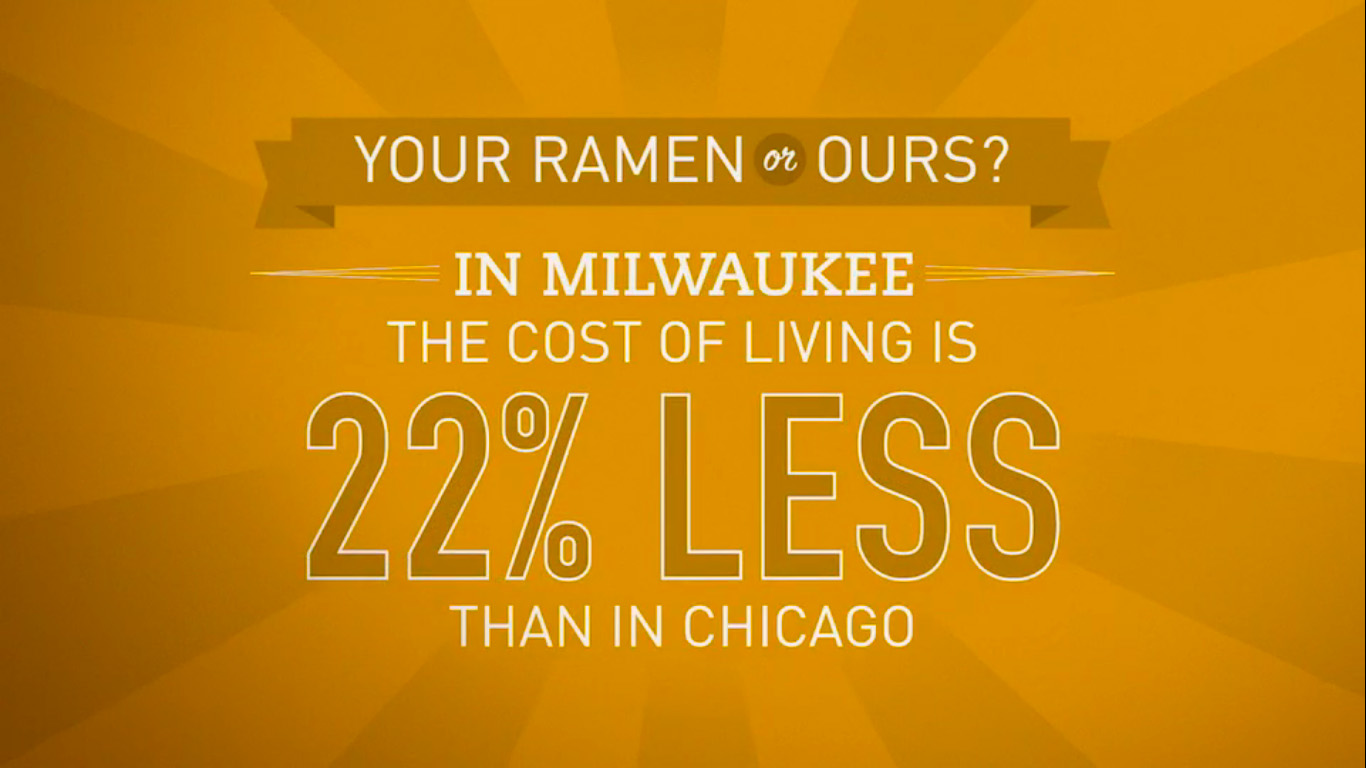

A state government-funded ad campaign aimed at recruiting younger workers to move to Wisconsin from Chicago touts cost of living as an critical advantage. Indeed, the phrase “cost of living” pops up regularly in discussions about economic development at both the state and local levels, and at the personal level, in families’ discussions about career opportunities and financial futures.

But cost of living isn’t a standardized, hard-and-fast mathematical concept. And looking into how it’s defined and applied to specific places reveals less about empirical economic differences and more about the nuanced and fluid ways in which people make decisions about money and opportunity and lifestyle.

To get the obvious out of the way: No reasonable person can dispute that it’s more affordable, on the whole, to live just about anywhere in Wisconsin than the Chicago area. It’s an economic fact of life that it is more expensive in some geographic areas than others to buy or rent a home, stock up on groceries, get around by car or public transit, pay for basic utilities, obtain child care and healthcare services, and enjoy leisure activities like dining out or live music.

Just about any of cost of living calculation will largely rest, and reasonably so, on housing costs. However, there’s no one standard formula for how to use that information to determine cost of living.

“There’s a number of different ways to look at it,” said Matthew Kures, an economist with the University of Wisconsin-Extension’s Center for Community and Economic Development. “Cost of living is typically kind of the market basket of goods that people typically use on a daily basis, but really one of the biggest drivers of cost of living differences is housing costs. When people think of the price of a gallon of milk or the price of a gallon of gasoline, there’s certainly a regional difference between those costs, but the biggest driver is going to be housing costs.”

Cost-of-living calculations play an important role in the discussion Wisconsin is having in its attempts to retain and attract more young workers—which in recent years has been a struggle.

Calculations may vary

The Wisconsin Legislature is moving to provide more funding for the ad campaign, which is managed by the Wisconsin Economic Development Corporation. It’s likely to keep emphasizing that it’s cheaper overall to live just about anywhere in Wisconsin than in Chicago, or another big-city setting.

A variety of consumer-facing online tools help illustrate how specific cost-of-living numbers can be a bit mushy.

For instance, the cost-of-living comparison tool on Sperling’s Best Places, a city-ranking consulting company, indicates that living in Chicago is 32 percent more expensive than living in Milwaukee, and that a $50,000 annual income in Milwaukee has the same buying power as $65,933 in Chicago.

CNN Money’s cost-of-living calculator doesn’t spit out an overall percentage difference, but claims a $60,161 income in Chicago would equal a $50,000 income in Milwaukee.

A similar comparison tool on consumer-finance website NerdWallet, doesn’t offer information on Milwaukee, for some reason. It does allow comparisons for Madison, Green Bay, Eau Claire and Marshfield, though. This calculator indicates that Chicago’s cost of living is 14 percent higher than Madison’s, and that a $56,992 income in Chicago is needed to equal a $50,000 income in Madison.

Among a few tools intended to help people gauge the financial implications of a move, there’s a more than $5,000 difference in comparisons between Chicago and Milwaukee. For somebody in their 20s or 30s, contemplating a move from one to the other, that spread might signal the need for some tough decision-making, especially if they don’t have savings and/or is paying off student debt.

Granted, someone moving for a new job is often motivated by a higher pay rate than what they’re earning currently. If the new job is a move upward with higher pay, gaps in consumer cost-of-living calculations makes them less helpful in figuring out what kind of lifestyle that enticing pay bump will buy in a new locale.

These Milwaukee-Chicago comparisons are still similar in the bold strokes, yet have some notable differences — for instance, CNN and Sperling’s Best Places both show that utilities and healthcare are actually cheaper in Chicago than in Milwaukee.

Two online cost-of-living calculators — CNN Money and NerdWallet — cite the same data source. Each is based on info from the Council for Community and Economic Research, a national membership organization focusing on regional economies known as C2ER — its quarterly Cost of Living Index is as close to an industry-standard metric as one can find. Sperling’s Best Places list of data sources does not mention C2ER, and representatives at Sperling’s did not respond to requests for comment. These calculators are doing their own research, either through hands-on data gathering or cobbling together government data on factors like housing and income.

Federal agencies like the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics or U.S. Census Bureau do not issue cost-of-living calculations. However, these and other agencies gauge and release information about a variety of economic factors relevant to to cost of living. The Consumer Price Index, issued by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, charts the cost of common goods and services over time and across geographic areas; the Social Security Administration calculates its adjustments with this data. Other government agencies use “cost-of-living adjustments” to make sure that public employee salaries and some public-benefit payouts keep pace with inflation. The U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Economic Analysis releases biennial figures about income and geographic price parity at state and regional levels. And the Census Bureau gathers and analyzes data on incomes and housing costs. However, none of these figures provides the type of tidy summation that C2ER is offering.

Jennie Allison, a program manager with C2ER, said its Cost of Living Index relies on the voluntary participation of local governments across the country to source data. The index’s formula looks at the cost of about 60 different kinds of goods and services across categories that range from housing to veterinary care to fast food. One admitted flaw is that a different mix of cities may participate from one quarter to the next, so the Cost of Living Index doesn’t have the same capacity to show trends over time as, say, the Consumer Price Index.

The costs that C2ER accounts for in determining cost of living in a given place represent a complex mix of needs and wants. For the third quarter of 2017, for instance, the calculations span 57 different items or services and assigns different weights to each. The highest-weighted items include rent, mortgage payments, gasoline, prescription drugs, power bills and repairs for a home washing machine. The lower-weighted items are all over the place, and include tennis balls, bowling, ground beef, hamburgers, peaches and toothpaste.

“The items do occasionally change to best represent the good and services currently available and what people buy,” Allison said. “Given that, an updated item will still represent the same category — for example, in 2015 we updated vegetable oil to extra virgin olive oil, however, it still represents cooking oil.”

Allison noted that the calculations change based on assessments of how relevant a particular good or service is at present. “This year we have updated the bowling item and are now pricing a drop-in yoga class, since it is more representative of how professionals spend their leisure time,” she said.

Where WEDC got its numbers

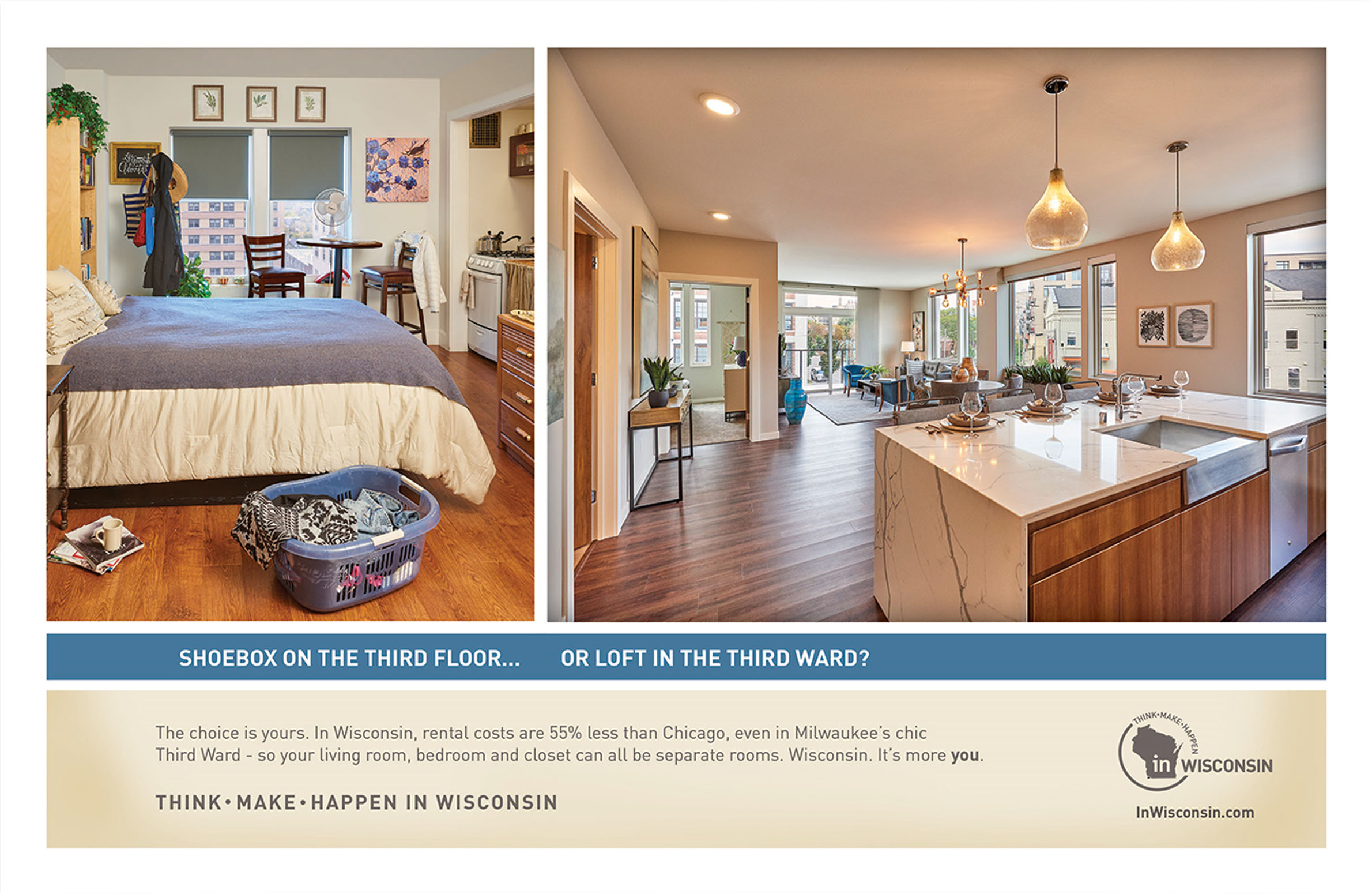

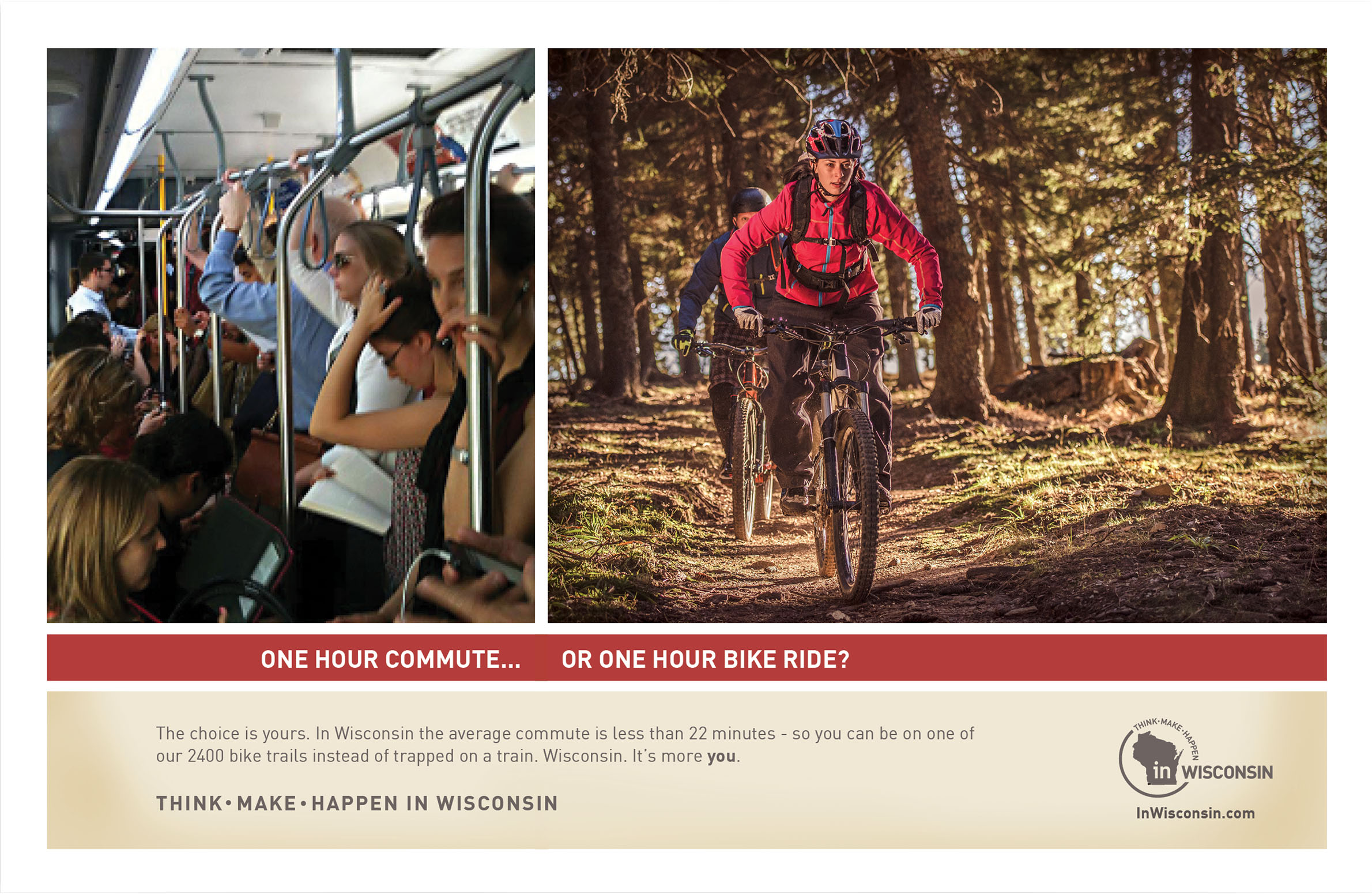

The Wisconsin Economic Development Corporation’s marketing campaign in Chicago implies that the advantages of the Badger State aren’t simply limited to lower costs, but that there’s a quality of life difference as well. One video ad cuts between a couple cooking dried ramen packets at home in Chicago and dining out on sumptuous high-end ramen in Milwaukee. (WisContext‘s own informal research suggests that, in either city, packaged ramen brands like Maruchan are dirt-cheap and meals at a nice ramen joint are moderately pricey.) Other ads argue that because Wisconsinites have shorter commutes, they have more time for outdoor activities and social gatherings.

WEDC spokesperson Mark Maley said its data sources for the marketing campaign include Sperling’s Best Places and RENTcafu00e9, an apartment rental and property management service. The latter source provided the figure that rent is 42 percent cheaper in Milwaukee than in Chicago, which translated into an ad that juxtaposed a crowded “third-floor walkup” in Chicago with a loft in the rapidly developing Historic Third Ward neighborhood just south of downtown Milwaukee. RENTcafu00e9’s own rental market data draws a distinction between luxury and non-luxury rentals, and it’s not clear where the Third Ward apartment pictured in the ad would fall.

Looking at RENTcafu00e9’s market trends for Milwaukeeand Chicago, it’s not clear where on WEDC got its specific figures. Overall, rents in Chicago are higher than rents in Milwaukee. Using RENTcafu00e9s figures for overall average rents, WisContext found that Milwaukee rents are about 38 percent lower — close, but not quite the figure WEDC cites. This could be due to market fluctuations over time, and it’s also possible that WEDC pulled its numbers from an earlier data set when rents were at slightly different levels in each city.

Sperling’s Best Places cites an array of government agencies and private sources for its data. RENTcafu00e9’s data, meanwhile, comes from its sister company, a real-estate research firm named Yardi Matrix, said RENTcafu00e9 spokesperson Andreea Curean. Yardi Matrix’s data largely comes from its own research, she explained.

“Rental rates are gathered by surveyors representing themselves as prospective renters, by telephone survey, from market-rate properties with [50 or more units],” Curean wrote in an email. “Properties incorporating a portion of low income households (i.e. IDA bond financed, or tax credit, properties), with the majority (or a significant component) of units rented competitively, are also included in rent surveys, reflecting competitive market rents not impacted by subsidy requirements.”

Like other sources that provide cost-of-living-related information for specific places, RENTcafu00e9 is only claiming to capture a subset of the relevant numbers one might consider when making a move.

“Our studies focus on the real estate market, and unfortunately not on the entire cost-of-living in a specific area,” Curean said.

Additionally, because the research RENTcafu00e9 uses accounts just for apartment buildings with 50 or more units, it misses rentals in smaller buildings, older houses that have been divided into flats and single-family house rentals — and there are plenty of each in both Milwaukee and Chicago. Of course, these rentals will also tend to be more expensive in Chicago than in Milwaukee, and Curean asserts that they’ll follow the same geographic variations as rentals in larger buildings.

What younger workers really want

It’s simply the nature of marketing that a campaign like WEDC’s speaks to experiences and narratives more than it does to data-driven decision making. Many of the ads are running on the Chicago Transit Authority’s mass-transit elevated trains and subways, and tell an implied story about bedraggled commuters who’d find relief and fulfilment if they moved to Wisconsin.

Riding “the L” might be stressful, but a Chicago Reader report published in late February 2018 found that plenty of the city’s riders still prefer it to living in a place without robust rapid transit. Predictably, commentators in Chicago have lambasted the ad campaign, critiquing a perceived air of generational disconnect and questioning why the CTA is running ads that cast aspersions on public transit. A story in The Outline presented evidencethat the ads deliberately target only a certain demographic of younger Chicagoan — those who are white and upwardly mobile. In the wake of the Reader‘s story, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported that even a couple of Milwaukee business figures had qualms about the ad campaign.

The bigger question is how well various cost-of-living figures support the broader argument Wisconsin’s economic development officials are trying to make to younger workers: The state is an advantageous place to move to (and move back to), for both lifestyle and career reasons. Just as these numbers can’t capture all the tangible and intangible factors people consider when picking a place to live and work, a marketing campaign doesn’t represent the more complex conversation that goes into steering a state’s economic future.

“We’re talking a lot about the kind of supply side for labor — how do we get individuals here from other places to become part of communities — but I think we also have to focus on the demand side as well,” said Matthew Kures with UW-Extension. “Are we creating the types of jobs and types of career advancement opportunities that young people want?”

Another part of the narrative that might be resonating less and less with time is the notion of making a big move at all.

“People are just simply less mobile than they used to be,” Kures said. “People are more rooted in place for a variety of reasons.”

People who do move might choose to live in a bigger, more expensive city for access to what UW-Madison economist Tessa Conroy calls “thick labor markets” — areas where there’s a high concentration of employers and opportunities — in addition to amenities ranging from cultural events to natural beauty. And sometimes the opposite trade-off makes sense.

“You can imagine for some families, for example, for their income to go further is really meaningful and they might want to have a lower cost of living somewhere else even if it means giving up those amenities,” said Conroy, who is also an economist with UW-Extension’s Center for Community and Economic Development.

Jennie Allison of the Council for Community and Economic Research acknowledged that to really use that organization’s data, a person considering their future job and lifestyle choices will be thinking about much more than the bare numbers.

“I guess wherever you live there’s trade-offs, right?” Allison said. “You can say, why would someone want to live in a higher cost-of-living area when you could obviously live somewhere that’s a little cheaper, but I think that’s where some personal preferences are in play — you want to live based on what amenities are important to you, and of course there are other factors.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us